Stalin’s Architect: Deyan Sudjic retraces the career of Boris Iofan

Deyan Sudjic’s new book, Stalin's Architect: Power and Survival in Moscow, chronicles the life and work of architect Boris Iofan (1891 – 1976)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The aesthetics of totalitarianism are very much back in the news. One of the struggles with imposing sanctions on modern-day kleptocrats is that ownership can be obscured. Authorship, however, is much harder to conceal. There’s a certain shared familial likeness in the catalogue of confiscated architectural monstrosities alleged to be owned by sanctioned Russians; overblown classicism, either ostentatiously ersatz or much-buffed original. Modern architecture is conspicuously absent. The classical orders, debased through grotesque inflation, have been the symbols of choice of oligarchs, plutocrats, strong men, and dictators, elected or otherwise, throughout the 20th century and now well into the 21st. Deyan Sudjic’s new architecture book, Stalin's Architect: Power and Survival in Moscow, chronicles the life of one of the most prominent purveyors of this style, the architect Boris Iofan (1891 – 1976).

Boris Iofan, his wife Olga, his brother Dmitry, and his team with their prize-winning design in the international competition for the Palace of the Soviets.

Iofan, who was born in the Ukrainian city of Odessa, relocated to St Petersburg as a youth and then undertook his architectural studies in Italy, where he became a passionate and committed neo-classicist. His political sympathies were communist, however, and he was driven out of Italy in the early 1920s by the rise of fascism.

He arrived back in the newly minted Soviet Union just as the wave of ideological modernism – in art, design, theatre, and literature as well as architecture – began rising to its peak. The country’s pavilions at the 1937 Paris Expo and the 1939 New York World’s Fair, and the monumental House on the Embankment in Moscow, completed in 1931, are all prime examples of Iofan’s work and of the Socialist Classicism that defined the Stalinist era.

Vyacheslav Andreyev’s sculpture under installation for Iofan’s Soviet Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

Sudjic charts Iofan’s career, with his early Constructivist-influenced buildings informed by both his refined classical sense of proportion and his expedient stylistic transition to suit the prevailing regime. Against a backdrop of political and social turmoil, Iofan ploughed on, surviving, quite literally, due to Stalin favouring his skills (there are no surviving images of the two men together). It was life on a knife-edge and for many creative Russians, living or dying meant not just compromise and collusion, but the arbitrary and capricious nature of the purges.

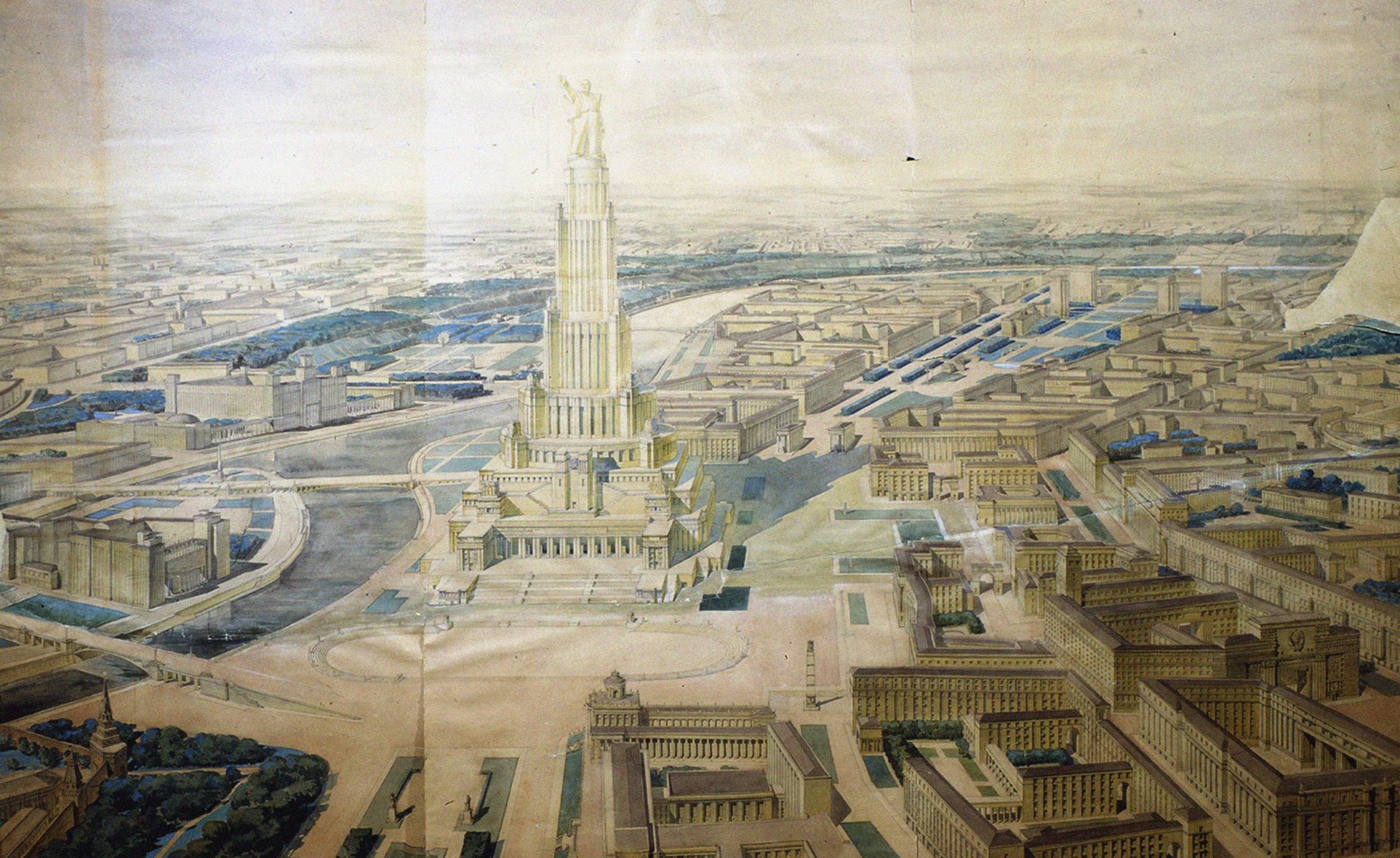

Iofan navigated this landscape of terror and should have delivered its crowning glory in the form of the competition-winning design for the Palace of the Soviets. This megalomaniacal plan for what would have been the world’s tallest building, topped by a statue of Lenin, was to be built on the site of the 19th-century Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, blown up especially in 1931. The Second World War and the advancing German army put paid to the palace’s completion.

One of Iofan’s many unbuilt designs for the constantly evolving Palace of the Soviets in Moscow

Sudjic has trodden this ground before in an earlier book, The Edifice Complex (2011), which tackled the link between architecture and power, or how dictators of every stripe inevitably end up cementing their rule through buildings. That tendency is by no means a preserve of the right or left, although the latter’s monuments tend to be cloaked in a veneer of social progress, however thin.

Iofan’s life straddles these contradictions. After the war, Stalin sacked Iofan and placed the notorious Lavrentiy Beria in charge of the Palace of the Soviets project. It stalled, although its visual legacy is clear in Moscow’s ‘Seven Sisters’ towers, built from 1947 to 1953. Stalin’s death that year effectively ended Iofan’s career. Nikita Khrushchev included architecture in his list of reasons to denounce the Stalin era and it seemed there was no way back.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Iofan’s Soviet Pavilion under construction for the Paris Expo of 1937, with Vera Mukhina’s huge sculpture as its high point.

Architecture and politics are never far apart, but Boris Iofan’s life and work blended the two to a deeply uncomfortable degree. Having survived his patron’s raging despotism, he carried on practising quietly until the end of his life, living in a modest apartment in the House on the Embankment, a home for the Soviet elite, perfectly placed to overlook the Kremlin. During the purges, around one third of the building’s tenants were murdered. Born from a life that must have been shaped in some way by fear, Iofan’s architecture gives off a chilling muscularity.

INFORMATION

Stalin's Architect: Power and Survival in Moscow, by Deyan Sudjic

Published by Thames & Hudson, £30

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.