Seratech’s innovative sustainable cement wins Obel award 2022

The 2022 Obel Award goes to Seratech’s carbon-neutral composite cement

Mikey Massey - Photography

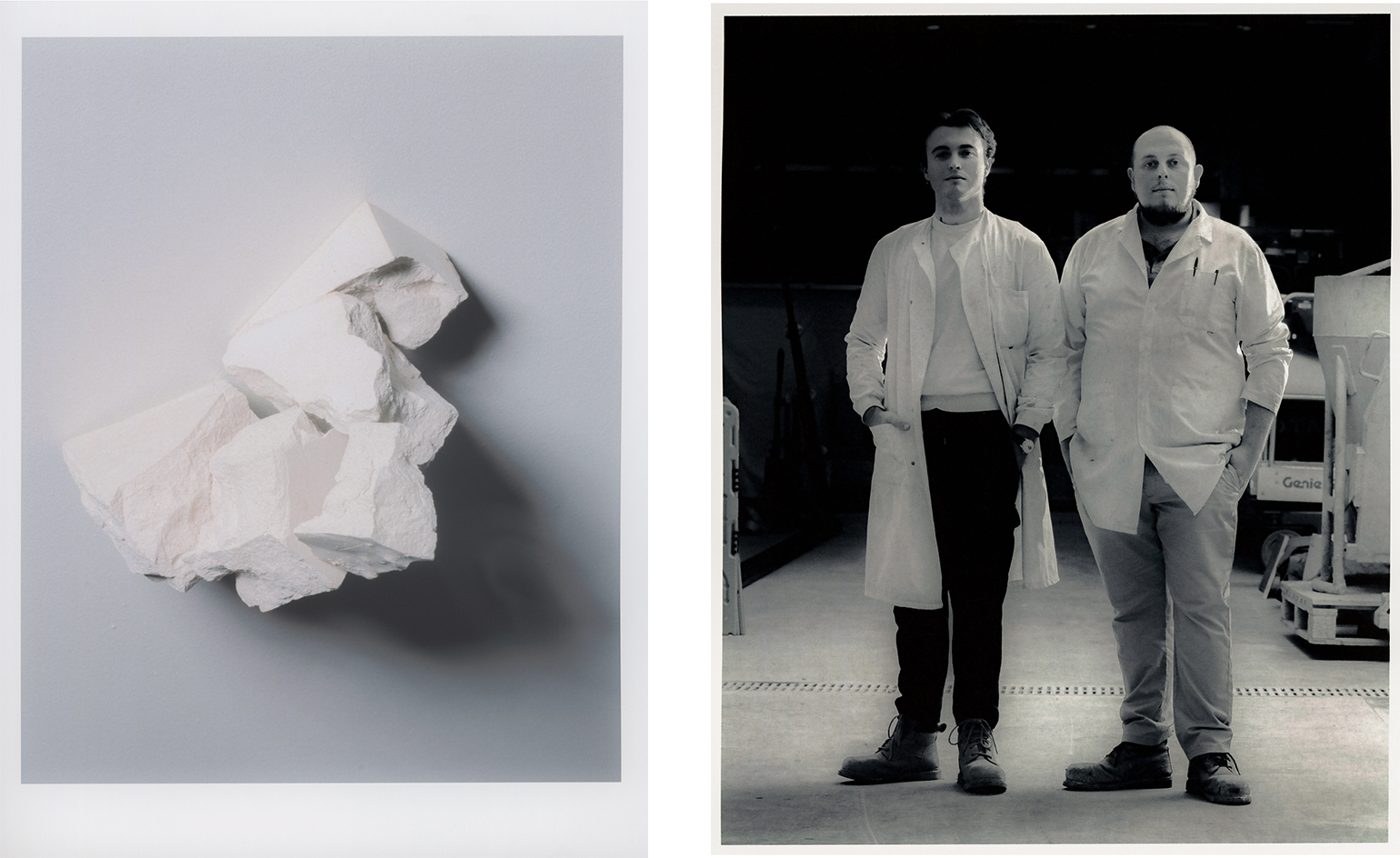

Imperial College London’s Structures Laboratory, or ‘the concrete lab’, is a slightly daunting place where large machines clang and chunks of grey matter set in moulds. However, everyone here is very convivial and jolly greetings abound. In the midst of this orderly yet experimental zone, a banterous pair of young British scientists, Sam Draper and Barnaby Shanks, head towards a small back room where they are scaling up carbon-neutral concrete from tiny cubes to bricks.

Wait, carbon-neutral concrete? Concrete has been a strong, convenient and attractive (to many architecture lovers at least) material used for buildings, cities and infrastructure for centuries – yet now, as the second most consumed material after water, it is responsible for around eight per cent of the world’s man-made carbon emissions. Does what’s happening in this lab in South Kensington mean that, potentially, that eight per cent could be neutralised?

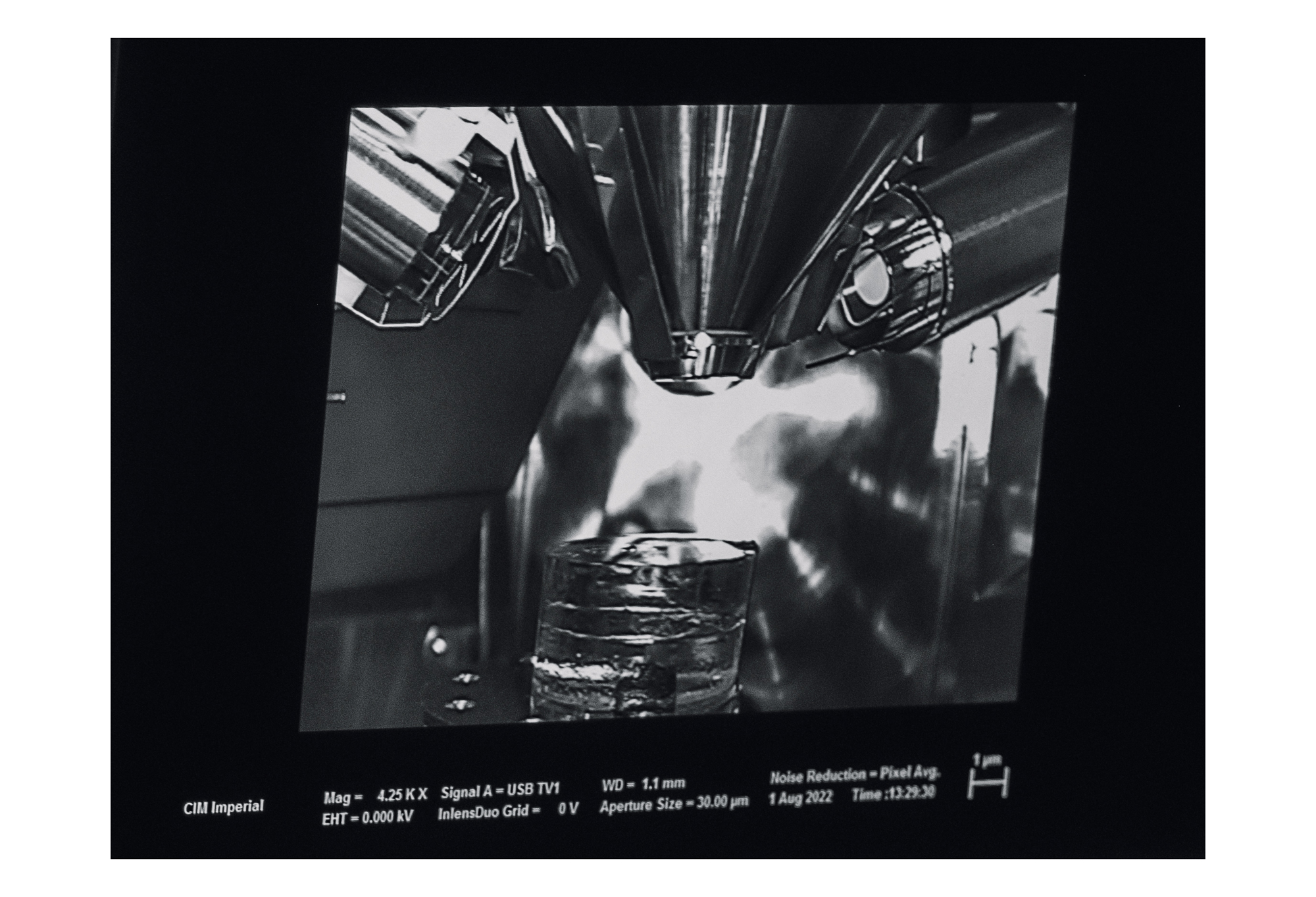

The inside of a scanning electron microscope (SEM), showing the detectors. The pair use this equipment to look at the microstructure of cements.

In theory, yes. And Draper and Shanks, a pair of PhD students who have set up under the name Seratech, have just received the Obel Award to help scale up their work towards this goal. Conferred by the Copenhagen-based Henrik Frode Obel Foundation, the annual global prize prides itself on its responsive, expansive approach to architecture – awarding projects that Bare groundbreaking, socially meaningful, and environmentally positive.

‘As an architecture award, we like to be unpredictable,’ says Jesper Eis Eriksen, head of programme at the foundation. One of the things that makes the award stand out is its ability to shape-shift at the pace of global debate, he explains. Winning projects include a community therapy centre and textile workshop in Bangladesh designed by Anna Heringer(awarded 2020), and Carlos Moreno’s 15-Minute City urban concept (awarded 2021). ‘Architecture needn’t just be architecture. Architecture is also an activity of the mind,’ adds Eis Eriksen.

The award selection process relies on a network of interdisciplinary experts and an esteemed jury, whom Eis Eriksen describes collectively as courageous, experienced, intelligent and gentle: ‘They recognise the need to be challenged and surprised.’ The jury includes chair Martha Schwartz, a landscape architect and urbanist known for her sensitive approach to the environment; Louis Becker, design principal at Henning Larsen Architects, a Scandinavian practice with a sustainable approach; Kjetil Trædal Thorsen, co-founder at the boundary-breaking architecture and design studio Snøhetta; Xu Tiantian, founding principal at DnA_Design and Architecture, adept at blending buildings and landscape; and Wilhelm Vossenkuhl, professor emeritus at the University of Munich, who specialises in the meeting of architecture, design and philosophy. As well as their professional excellence, all were chosen for their humanitarian approaches and diverse life experiences.

An architectural brick made of Seratech’s carbon-neutral composite cement. Bricks such as this one were used to create a ‘Crinkle Crankle Concrete’ wall for the 2022 London Design Festival.

This year, the jury’s award focused on reducing embodied carbon emissions in the built environment sector, which is responsible for almost half of global CO2 emissions every year. After reviewing multitudes of diverse projects, an initial bout of pessimism gave way to optimism, detailed deliberation and consultation with science professionals. The jury then made a unanimous decision on Seratech’s invention.

Could the key to significantly reducing the built environment’s carbon footprint really be found in the cement mixer? The Obel Award jury thinks so. They admired both the material’s ambition and simplicity, and commended it for how it could be easily integrated into existing processes and production lines. Back in the lab, Draper unpacks the theory behind Seratech’s ambition: ‘You need solutions that are scalable, that work everywhere in the world, that use naturally abundant materials, and you need relatively simple processes, too.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘The beauty of the idea is that you can just use it as normal concrete,’ says Shanks. ‘There are other carbon-neutral materials, but they can be limiting because they can only be precast, cured in a lab in special conditions and shipped elsewhere. We want people to retain the freedom to use concrete the way that they are used to. We don’t want to limit people in any way because we’ll just lessen the amount of impact we can have.’

Seratech’s carbon-neutral composite cement uses olivine (a common mineral that is the primary component of the Earth’s crust) and waste CO2 from flue gases, which is broken down to release silica (required to bind cement together) and magnesium, which is then combined with waste CO2 gas to make magnesium carbonate. This mix can replace up to 40 per cent of the cement mix and it sequesters around twice as much CO2 than the normal Portland cement – so when the two are blended, the emissions are offset.

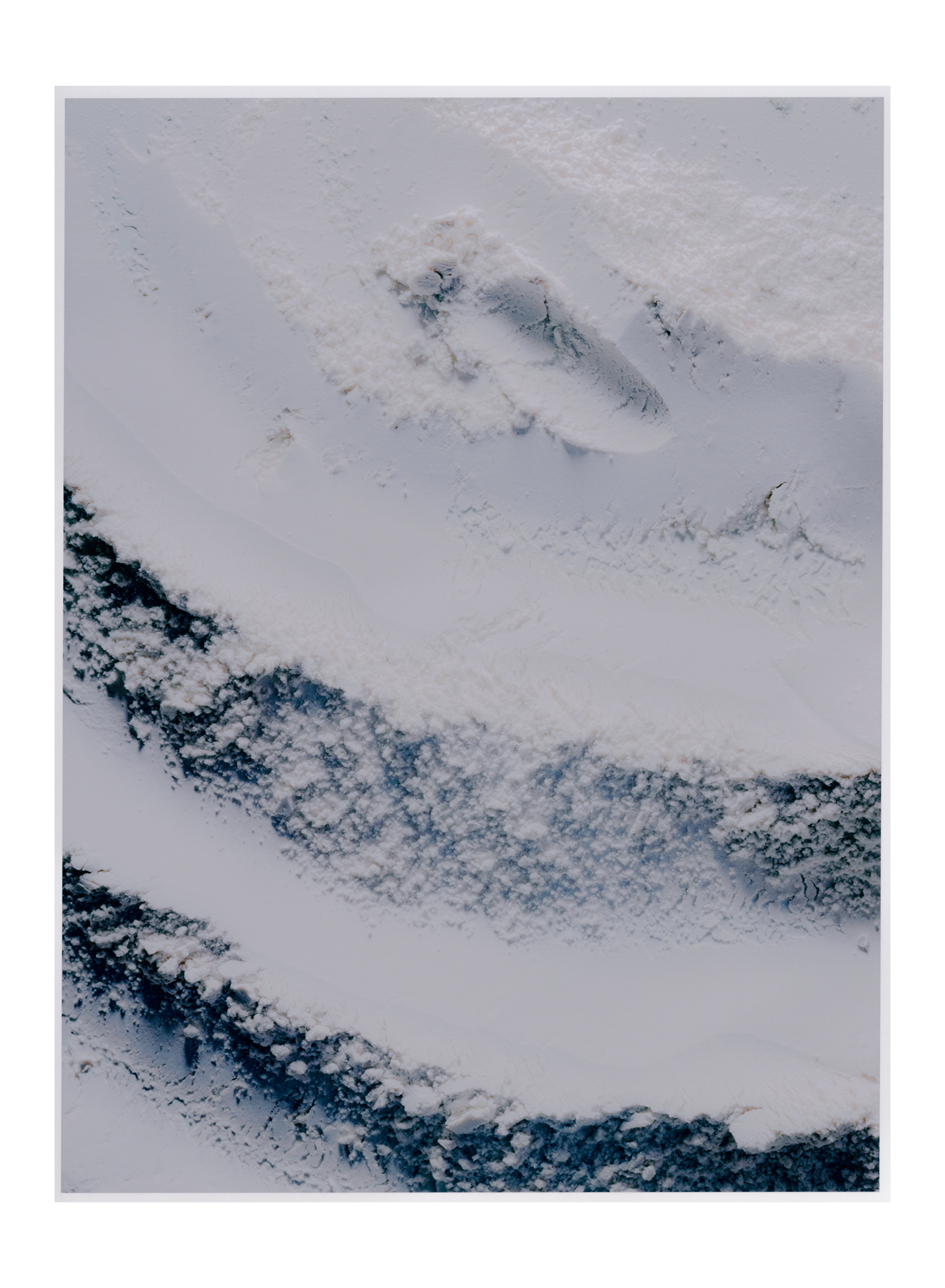

The Seratech process also produces silica, which can be used as a supplementary cementitious material in concrete, reducing the amount of Portland cement in the concrete by up to 40 per cent

‘This is evolution, not revolution,’ says Draper, who has a background in structural engineering. ‘People have done similar things before.’ For example, chemically, the mix is similar to fly ash concrete, a product that already exists on the market. Fly ash, a waste product of the coal industry, also contains a high proportion of reactive silica and can be used as partial cement replacement; it is cut with cement at a similar percentage, which reduces, yet doesn’t neutralise, its impact. The way Seratech processes its olivine is similar to ‘enhanced weathering’, where the powdered mineral is dispersed in the environment to sequester atmospheric CO2 as magnesium carbonate.

Instead of seeing CO2 as a ‘waste product’ of the cement-making process, Draper and Shanks see CO2 as a ‘co-product’ that needs to be designed into a process so it retains its value as a material. The CO2 in their recipe is sequestered during the production of the cement replacement, and contributes to the success of the material. Seratech’s approach is staunchly realist, grounded in an understanding of supply chains and industry, as much as the science of chemistry. ‘It’s not a silver bullet. It’s part of a toolkit,’ says Shanks.

For their part, Shanks and Draper are full of energy, excitement and optimism. They see their Obel Award win as a key moment to reach new audiences, inspire young scientists and encourage cross-disciplinary work: ‘Public opinion is an important factor in an industry trying to do better instead of defaulting to the status quo of the last 40 years,’ says Shanks. ‘Nothing’s untouchable – there are better ways to do things, and now there is a desire to do things better, we need to find solutions.’

INFORMATION

obelaward.org

This article appears in the November 2022 Art Issue of Wallpaper*, available from 6 October in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.