Raw Concrete: Barnabas Calder explores the beauty of Brutalism

Concrete seems to be having a long, lingering moment, a riposte to decades of disdain, disgust and general disinterest. Why is it that the spectacular forms and structures of the 50s, 60s and 70s have failed to win themselves any favours with the public? Perhaps the architects of the era didn't help matters by appearing aloof and detached from the general population, apparently committed to concrete for ideological and aesthetic reasons. As a result, concrete is still a hard sell for the masses.

Barnabas Calder aims to address this narrative. His book, Raw Concrete, has been many years in the making. 'The original inspiration was to break it to a disagreeing world that there was some value in this stuff,' he admits. Yet as he researched, Brutalism started trending and a groundswell of support started bubbling up. As a result, Raw Concrete is the latest in a small library of books that are predicated first and foremost on concrete's undeniable aesthetic strength – especially in the hands of a skilled photographer.

Calder's emphasis shifted to examining the circumstances of concrete's high period of design and what, if anything, it means. 'It's the last period in which the increase in wealth wasn't undermined by self doubt,' Calder explains of the 1970s. In the UK at least, investment in housing, education and culture saw a huge expansion. Although he admits to a certain amount of 'terrifying destruction' to facilitate the new world, concrete spearheaded this change. As Calder tells it, concrete is not about austerity, but innovation and prosperity. 'It's still both misunderstood and wildly underestimated,' he says with some frustration, 'the period produced masterpieces equal to anything else produced in architecture.'

Raw Concrete is still first and foremost a personal journey through some signature places and spaces, exploring Calder's own experiences as well as the story behind the construction of some of the major slices of concrete landscape – the Barbican, the South Bank, the National Theatre. Despite the revival, concrete might never be fully appreciated. It acts as a form of landscape, both literal and mental, yet is something not everyone is willing to surrender to. It's this all-encompassing facet of the material that is frequently held against it, dismissed as the concrete jungle, with overwhelming cliffs and aggressive atmosphere, a visual language of fortifications and bunkers, war and defence.

Calder's book reveals the inherent humanism of Goldfinger, Lasdun, et al, of the people behind the perceived arrogance. His contention is that 'the best Brutalist architecture turns necessity into the sublime' and it's true that the confidence of these buildings has rarely been seen since.

Yet ultimately Brutalism's break out moment still hasn't endured it to the masses – just because a building adorns a tea-towel doesn't make it universally admired. Raw Concrete might not win over any hearts and minds, but we would do well to absorb the central thesis – that the products of innovation and confidence still have much to teach us – as self-doubt continues to creep into the national conversation.

Trellick Tower, designed by architect Ernö Goldfinger in the late 1960s, is a landmark of West London. Photography: Barnabas Calder

The South Bank Centre in London was built in 1951 as part of the Festival of Britain. Photography: Barnabas Calder

A heap of models used by the architects during the design process of the National Theatre. Photography: RIBA/Lasdun Archive

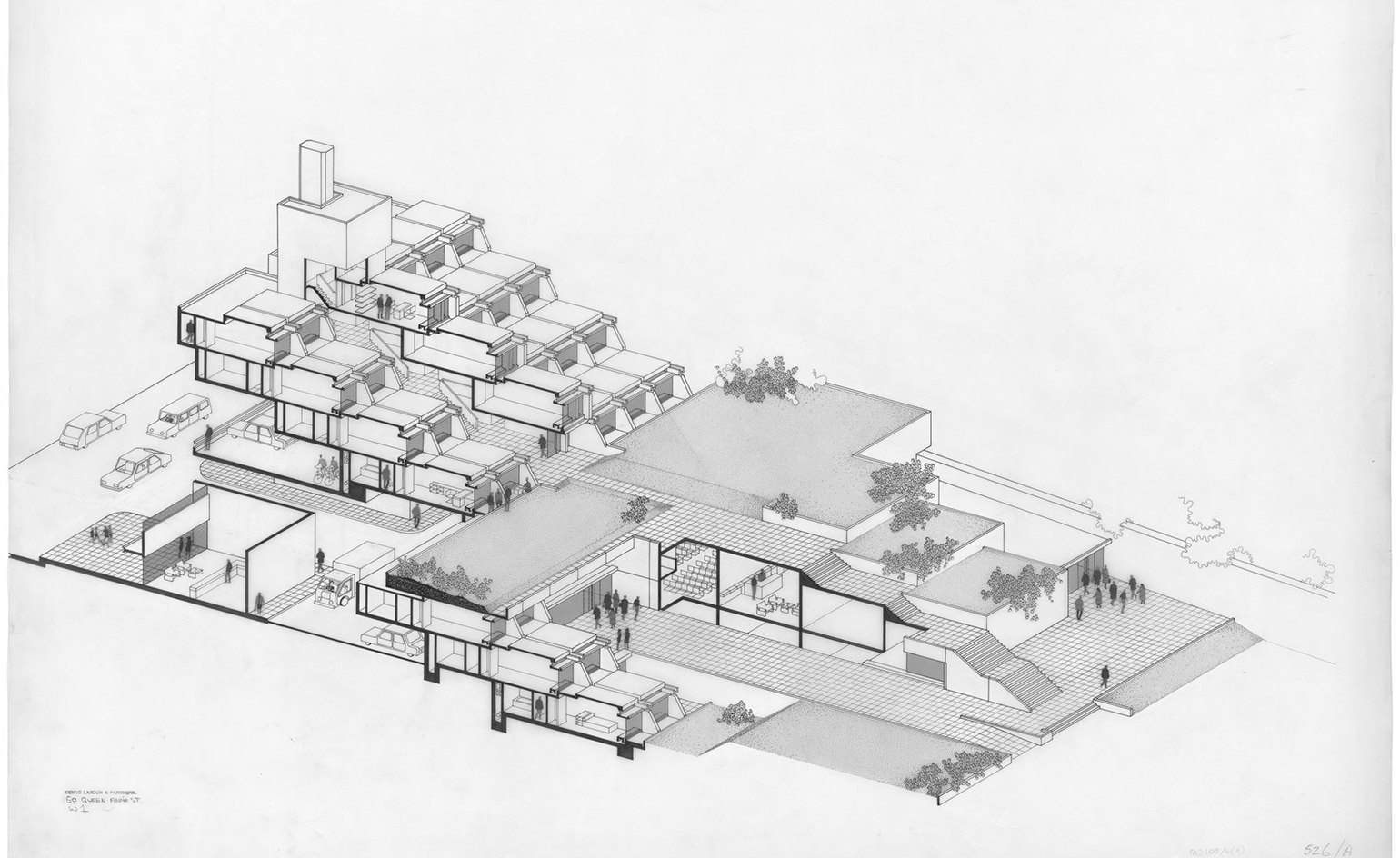

A drawing produced by Denys Lasdun & Partners to show the stepped section of New Court. Photography: RIBA/Lasdun Archive

INFORMATION

Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism by Barnabas Calder, £25.00, is published by Penguin. For more information, visit the website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.