A love letter to the panache and beauty of diagrams: OMA/AMO at the Prada Foundation in Venice

‘Diagrams’, an exhibition by AMO/OMA, celebrates the powerful visual communication of data as a valuable tool of investigation; we toured the newly opened show in Venice’s Prada Foundation

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

You will look long and hard for any OMA/AMO drawings at ‘Diagrams’, the new show at the Fondazione Prada event in Venice, even though it is curated by Rem Koolhaas, the practice’s lead partner. The foundation’s show, which coincides with the Venice Architectural Biennale 2025, does feature one image, amongst nearly 200, of the Scalo Farini masterplan for Milan by the Dutch studio. Other than that small moment, its work is absent from this wide-ranging, frequently stunning, always fascinating exhibition. One might have expected more.

Explore OMA/AMO’s ‘Diagrams’ at the Prada Foundation in Venice

At OMA in the 1980s, Rem Koolhaas and his early colleagues, such as Elia Zenghelis, incorporated the diagram into the wealth of drawing types used by architects to create work. Added to the repertoire of the section, plan and perspective, the diagram puts the focus on the building’s use or programme and how this might suit the user first and create form second. The Seattle Public Library’s wonky stack, for example, emerges from layers of different uses: public spaces on the lower floors, the book stack above, and the building’s admin capping it all. The De Rotterdam resulted from separating out multiple uses in a diagram and then bringing them together in a dramatic aggregated form.

Timeline, 2025 / Distribution of diagrams on display by topic and year of production

The ‘Diagrams’ show, however, is a wider cultural history of the diagram, beginning in the early Renaissance and coming up to the present day, an expression of OMA’s affinity for the diagram rather than examples of the firm's use of it. An arrangement of troops in Machiavelli’s book, the Libro della arte della guerra (first published in 1521), is probably the oldest work in the exhibition; images of photovoltaic cell efficiency are perhaps the most recent. Koolhaas and fellow curator Giulio Margheri have arranged the historical documents into nine different 'urgencies' – the vital concerns of humanity, such as health, migration, inequality and resources. These themes are given an overview in identical vitrines in the central space on the first floor of the palazzo, with each room off that central space exploring the subject in more varied hangs. The war room, for example, has banked vitrines redolent of, well, a war room.

Elwin J. Woodward / Historic and prophetic diagram of the world: God’s plan of salvation for law breakers, 1912 / Colored lithograph, exhibition copy / David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford University Libraries

In previous exhibitions, such as the interesting but uneven ‘Countryside’ at the New York Guggenheim in 2020, Koolhaas included a series of awkward, unpalatable or banal images to prove a wider point. In ‘Diagrams’, these moments are kept to a minimum – interestingly, the ugliest diagrams are in the built environment section – providing not only an engrossing insight into the way humans communicate collective needs to each other, but also exemplars of panache, style and in some cases, beauty.

One of the most striking moments in the show is a series of 16 images by the Black activist and sociologist WEB Du Bois for the Paris Exposition in 1900. Not only do they convey the enormity of the massive social progress made after the abolition of slavery, but they are also remarkably clear and simple, proto-modernist somehow.

William Playfair / Universal commercial history from 1500 to 1805, 1805 / Printed book / In William Playfair, An Inquiry into the Permanent Causes of the Decline and Fall of Powerful and Wealthy Nations (London: W. Marchant printer, 1805) / STRONG ROOM OGDEN B 47, UCL Special Collections, London

There is a longer history to the aesthetic of the diagram, however. Koolhaas also suggests that modernism (and, presumably, modernist architecture) was the rise to aesthetic preeminence of an already existing way of thinking. The diagram, he explains in the catalogue, is 'a form of thinking that almost transcends aesthetic style or period'.

Often, there is a strange combination of absolute bathos to the clarity. In 1869, Charles-Joseph Minard depicted the losses of the French army during Napoleon’s Russian campaign in 1812–13 as a thick black line leaving Paris. As men die on the road to Moscow, the line thins and narrows until it returns to Paris a mere thread. Designers use beauty to convey often ugly things.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

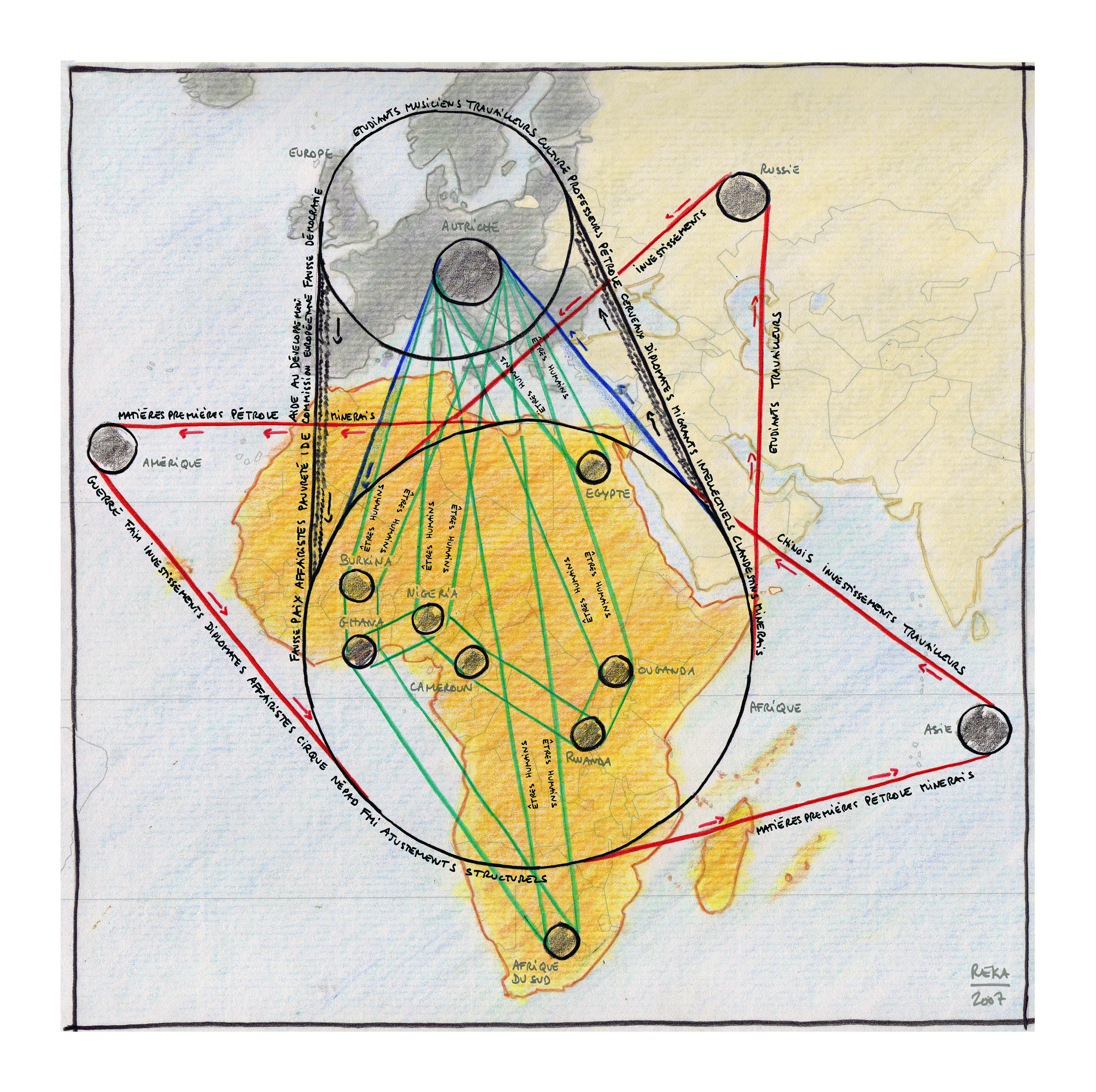

Philippe Rekacewicz / The African big wheel, 2007 / The wheel symbolizes permanence and continuity in the context of a profoundly unequal exchange, drawing, color pencil and ink, exhibition copy / Courtesy Philippe Rekacewicz

There is much to unpack in this wonderful show, curated with sensitivity but also clear admiration for the work selected, born from OMA/AMO’s internal understanding of the power of a good diagram. The thematic organisation highlights the hidden purposes behind the apparently neutral arrangement and display of material in the diagram, as does the focus on authorship. There are clusters of work by Minard and Du Bois, but also others: the economist William Playfair and the cartographer Philippe Rekacewicz, for example. Together, though, this is an absolute must-see if you are visiting Venice for the 2025 biennale.

Tim Abrahams is an architecture writer and editor. He hosts the podcast Superurbanism and is Contributing Editor for Architectural Record