César’s palace: restoring Luis Barragán’s Casa Prieto-Lopez

Mexico City’s topography spans the remains of a drained lake, several waves of concrete urban sprawl in a valley surrounded by mountains, and the hard black volcanic grounds that lent inspiration to one of the city’s best examples of modern architecture – El Pedregal. This housing development owes its name, literally meaning ‘rocky place’, to the petrified lava that covered an area of some 80 sq km, deposited when the Xitle volcano erupted some 1,600 years ago. The area remained largely undeveloped until the mid-20th century.

This changed drastically in the 1940s, when Mexican architect and future Pritzker Prize winner Luis Barragán started working on El Pedregal, a residential experiment aiming at bringing together architecture and landscape. The project was well received by clients, who saw in the design a possibility for new beginnings in an unexplored part of town.

The area soon became a breeding ground for experimentation, accruing works by architects such as Max Cetto, Mathías Goeritz, Francisco Artigas, Pedro Ramírez Vázquez and, of course, Barragán. Casa Prieto-López was designed in the late 1940s by Barragán and is widely recognised as one of his most iconic residential projects. The house remained in the hands of the Prieto family until a couple of years ago, when it came on the market; the first from Barragán’s ‘golden period’ to be offered for sale. The biggest collectors in the world came calling, but it was eventually bought by businessman and art collector César Cervantes, who had moved to El Pedregal as a seven-year-old in the early 1970s and become mesmerised by the aesthetics of petrified lava.

Cervantes then invited his friend and fellow Barragán admirer Jorge Covarrubias to embark on one of the country’s most important restoration projects. Renaming the house Casa Pedregal, it soon became Cervantes’ biggest labour of love, with one clear objective – to rid the house of alterations added over time and return the design to its original purity. The team likened the process to ‘modern archaeology’, stripping down layers of recent history in search of the building’s beginnings and its original homely feel.

‘This house is not a museum. I wanted it to be a real house. I don’t even believe in museums; how am I supposed to live inside one?’ says Cervantes. ‘People think I don’t live here. They ask me why I have bottles of alcohol. They think they are props, but they’re not.’

Covarrubias, co-founder of local practice Parque Humano, confesses he had no idea where to start with the restoration. Even though his passion for Barragán was long standing, and he had worked in the past with Ricardo Legorreta, one of Barragán’s most proficient apprentices, this was the first project of its type for his office. ‘I did a lot of research about Barragán,’ recalls Covarrubias. ‘I felt an honest affinity with him, a real connection. I’m very interested in the formal representation of architecture, and the way poetry is constructed, and urban relationships.’

After studying numerous photographs, historical documents and local stories, and consulting with academics that specialise in Barragán’s work, the team bit the bullet and started on site, finding pleasure not only in the project’s possibilities but also its challenges. ‘Every single day, every moment, I discovered something new,’ says Cervantes. ‘The way the light bathes the walls, the way the colour changes with time, the relationship between the full and the empty.’

Cervantes confesses it was only when they were six months into the renovation works that he felt he could relax a little and breathe easy. And although the team’s mission had been to restore the house to its original state, they decided they also wanted to keep some memories and scars of the house’s life with the Prieto family, including marks on the wall where they had installed a lift, an old dividing wall, and a staircase.

Following 20 months of restoration works, the house is now back to its original midcentury form. Cervantes and Covarrubias modestly insist that they actually didn’t do much – at least nothing that Barragán hadn’t done before them. But they have breathed new life into this 66-year-old structure, which comes alive when Cervantes pumps up the volume of his sound system, reminding us that this is not a museum, but a real home.

As originally featured in the June Issue of Wallpaper* (W*207)

A staircase rises from the entrance foyer into an open-plan living and dining area

Cérvantes wanted the house to be restored to its original condition, and to be a real home

Pictured left: a perforated wall, a Barragán trademark, allows light to subtly penetrate internal spaces. Right: the minimalist fireplace, for cooler days in Mexico City, features the house’s original wall-hung companion set

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Parque Humano website

Photography: Adam Wiseman. Copyright Barragan Foundation / 2016, DACS

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

A nature-inspired Chinese art centre cuts a crisp figure in a Guiyang park

A nature-inspired Chinese art centre cuts a crisp figure in a Guiyang parkA new Chinese art centre by Atelier Xi in the country's Guizhou Province is designed to bring together nature, art and community

-

William Kentridge's fluid sculptures are a vivid addition to the Yorkshire landscape

William Kentridge's fluid sculptures are a vivid addition to the Yorkshire landscapeWilliam Kentridge has opened the first major exhibition to focus on his sculptures outside of South Africa at Yorkshire Sculpture Park

-

David Cronenberg’s ‘The Shrouds’ is the film for our post-truth digital age

David Cronenberg’s ‘The Shrouds’ is the film for our post-truth digital ageThe film director draws on his own experience of grief for this techno conspiracy thriller

-

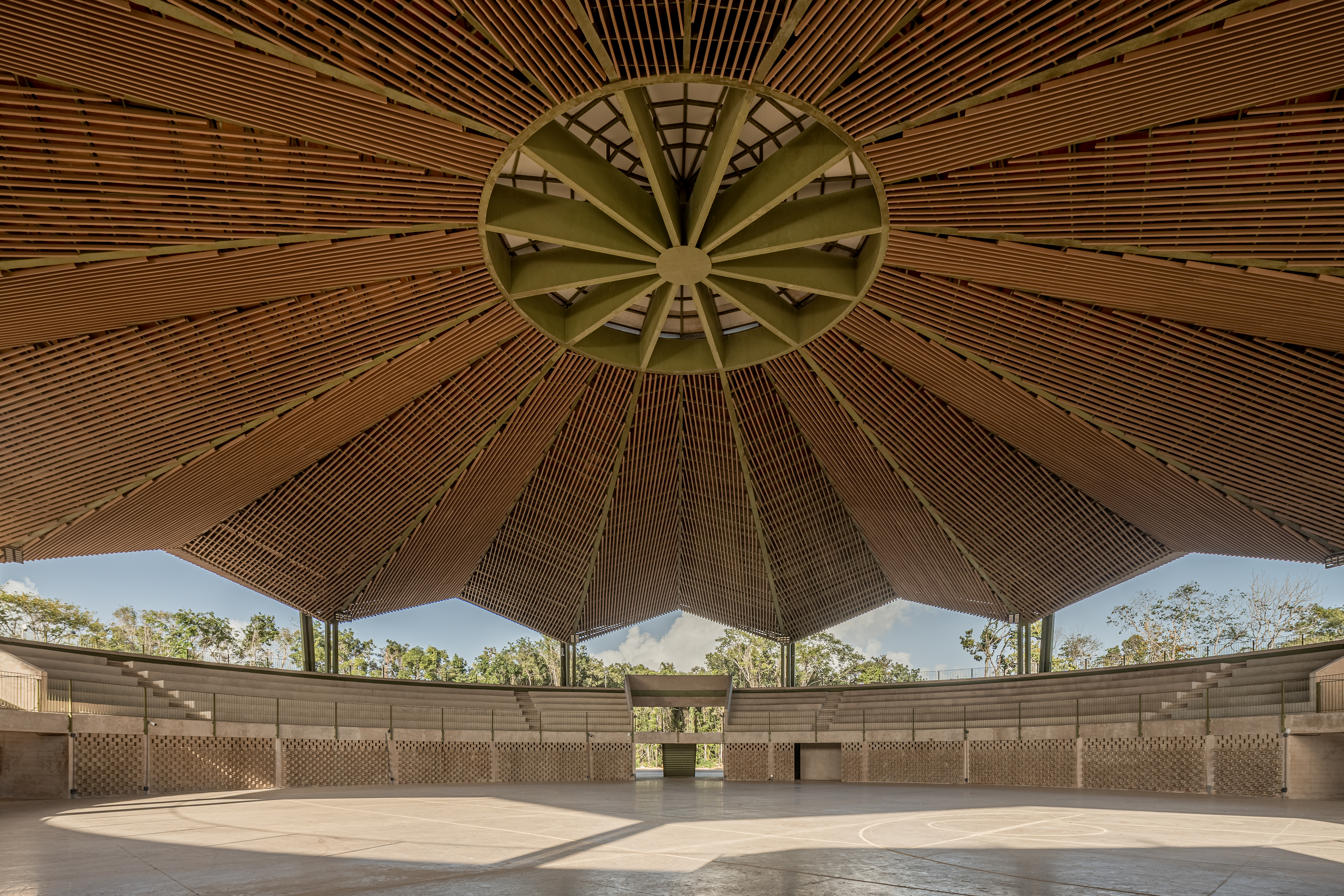

In Quintana Roo, a park mesmerises with its geometric pavilion

In Quintana Roo, a park mesmerises with its geometric pavilionA Mexican events venue in the state of Quintana Roo rings the changes with a year-round pavilion that fosters a strong connection between its users and nature

-

Casa La Paz is a private retreat in Baja California full of texture and theatrics

Casa La Paz is a private retreat in Baja California full of texture and theatricsLudwig Godefroy designed Casa La Paz in Baja California, Mexico to create deep connections between the home and its surroundings

-

Pedro y Juana's take on architecture: 'We want to level the playing field’

Pedro y Juana's take on architecture: 'We want to level the playing field’Mexico City-based architects Pedro y Juana bring their transdisciplinary, participatory approach to the Mexico pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025; find out more

-

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico‘Casa Mexicana’ is a new book celebrating the country’s residential architecture, highlighting its influence across the world

-

A barrel vault rooftop adds drama to these homes in Mexico City

A barrel vault rooftop adds drama to these homes in Mexico CityExplore Mariano Azuela 194, a housing project by Bloqe Arquitetura, which celebrates Mexico City's Santa Maria la Ribera neighbourhood

-

Explore a minimalist, non-religious ceremony space in the Baja California Desert

Explore a minimalist, non-religious ceremony space in the Baja California DesertSpiritual Enclosure, a minimalist, non-religious ceremony space designed by Ruben Valdez in Mexico's Baja California Desert, offers flexibility and calm

-

La Cuadra: Luis Barragán’s Mexico modernist icon enters a new chapter

La Cuadra: Luis Barragán’s Mexico modernist icon enters a new chapterLa Cuadra San Cristóbal by Luis Barragán is reborn through a Fundación Fernando Romero initiative in Mexico City; we meet with the foundation's founder, architect and design curator Fernando Romero to discuss the plans

-

Enjoy whale watching from this east coast villa in Mexico, a contemporary oceanside gem

Enjoy whale watching from this east coast villa in Mexico, a contemporary oceanside gemEast coast villa Casa Tupika in Riviera Nayarit, Mexico, is designed by architecture studios BLANCASMORAN and Rzero to be in harmony with its coastal and tropical context