William Kentridge's fluid sculptures are a vivid addition to the Yorkshire landscape

William Kentridge has opened the first major exhibition to focus on his sculptures outside of South Africa at Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Nothing is quite what it seems in the work of William Kentridge. The South African artist is hard to pin down, working in an eclectic range of mediums across media, from drawing, to tapestry, theatre, films and opera. Often political, often playful, Kentridge’s work considers significant themes – notably colonialism and accepted historical narratives – in unexpected, culturally curious ways.

It is a fluidity present in Kentridge’s largest exhibition to focus on sculpture outside South Africa. In ‘The Pull of Gravity’ at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Kentridge unites over 40 works, made from 2007 to the present day, in a large exhibition situated both inside and outside, becoming a striking focal point of Yorkshire’s landscape.

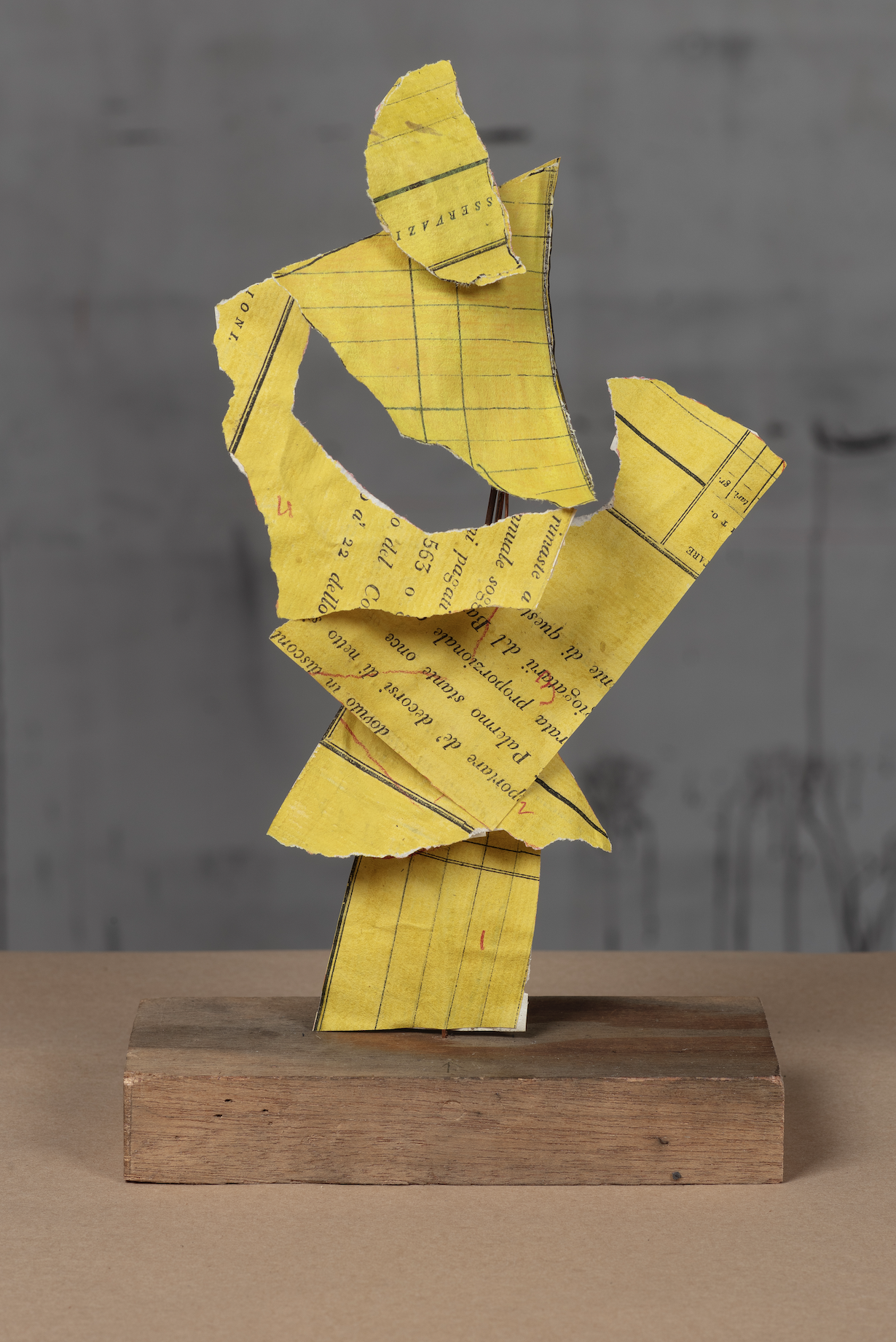

Outside, six new sculptures, Paper Procession, cut abstract shapes in bold tones of red, yellow and orange. Appearing to flutter in the air, they are grown versions of the 30cm originals inside, created from the torn pages of a cash book. They join imposing bronze Glyph works, the grown-ups to the Glypth series in the indoor gallery, composed of items from Kentridge’s everyday life – a typewriter, a coffee pot, scissors – which often began life as ink drawings. The process of becoming three-dimensional, of being teased and sculpted into voluminous life, is reflected in the exhibition’s name. Again, works are hard to pin down – viewed from one angle, you may see a cat, from another, a curving form.

William Kentridge, Paper Procession (Palermo Cash Book) I, 2023

‘A lot of the sculptures start as shadows or silhouettes,’ says Kentridge. ‘They start as something that's essentially without any dimension. The sculptures are extrusions of these two-dimensional works to something that then has a heft, a thickness and a weight. So they start as two-dimensional, they become three-dimensional, and then some of them revert to two dimensions, like the cat and coffee pot. They are only recognisable as a coherent form, even though they're three-dimensional objects, when you see them as a two-dimensional image from one particular monocular viewpoint. So these games of sculpture and anti-sculpture, equestrian statues that have the least right to think of themselves as equestrian statues, are part of the activities. I never thought of myself as a sculptor. After many years, I realised there was a large body of work which had expanded into space from the two-dimensional form. And now sculpture is certainly one of the languages.’

Weighty motifs, such as the equestrian statues, run throughout, from the bronze horse sculptures from 2010’s The Nose production – which started life as pieces of cardboard, twigs, rulers, and anything else Kentridge found lying around the studio – to the first presentation of the series of short films that Kentridge made during the first Covid-19 lockdown, Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot (2020-24).

Form, how it can be constructed and how it can be misunderstood, is most playfully explored in kinetic works, such as Singer Trio (2019), composed of sewing machines and megaphones, which project South African singer and choreographer Nhlanhla Mahlangu towards those entering the space.

Kentridge in his studio working on the preparatory plaster version of the monumental bronze Laocoön, Johannesburg, 2021

Throughout, scale is tweaked, emphasised, subverted. ‘Some of the glyphs are expanded to the bronzes, which are in the corridor of the exhibition, [and] are about a metre high. And then some of those [are expanded] to this much larger scale. I think the shifting in scale is very familiar from working with projections with film, where the scale varies according to the lens of your projector and the distance of the projector from the wall, but it's not fixed into any one particular size. And some of the film work needs to be projected very large, and some is fine if it's on a monitor, and much smaller. And the same with the sculptures, some of them can expand. When they expand, of course, they change considerably from the smaller form. So if anyone has the energy, they can go up and down between the large sculptures and the small version in the gallery with the glyphs and see how they've been altered. It's not simply a mathematical enlargement. We might start with a digital enlargement, cut out as a polystyrene, and then, using an electric carving knife or a saw or a machete, the proportions are changed, different things are added. Things are shifted. Angles vary, and it becomes a different sculpture based on the original but not identical to it.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

William Kentridge, Singer Trio, 2019

The lush acres of Yorkshire Sculpture Park felt like a natural choice for Kentridge to celebrate form and scale. ‘There are beautiful views and expanses,’ he says. ‘And I was very happy to find a place to show an extensive body of sculptural work, which I hadn't shown in Europe, and also, for the first time, to look at showing sculpture out of doors. This is very much in the tradition of the grand gardens of the grand parks, with artificially made lakes and nature as a canvas to be painted on, rather than a wild terrain to be found.’

His bold, sculptural works are a natural addition to the landscape. ‘The coloured sculptures were a sense of thinking about how to make sculpture visible against a landscape. I have a sense they're going to look best when it's winter and the sky is dark, but I'm very pleased with how they look already in the middle of the Yorkshire summer, which feels almost as hot as the Johannesburg summer. I was expecting rain and drizzle the whole time, so I'm a bit disappointed.’

‘William Kentridge: The Pull of Gravity’ is at Yorkshire Sculpture Park until 19 April 2026

William Kentridge, Cursive, 2020

Hannah Silver is a writer and editor with over 20 years of experience in journalism, spanning national newspapers and independent magazines. Currently Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*, she has overseen offbeat art trends and conducted in-depth profiles for print and digital, as well as writing and commissioning extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury since joining in 2019.