Kunlé Adeyemi on climate change, architecture and the power of water

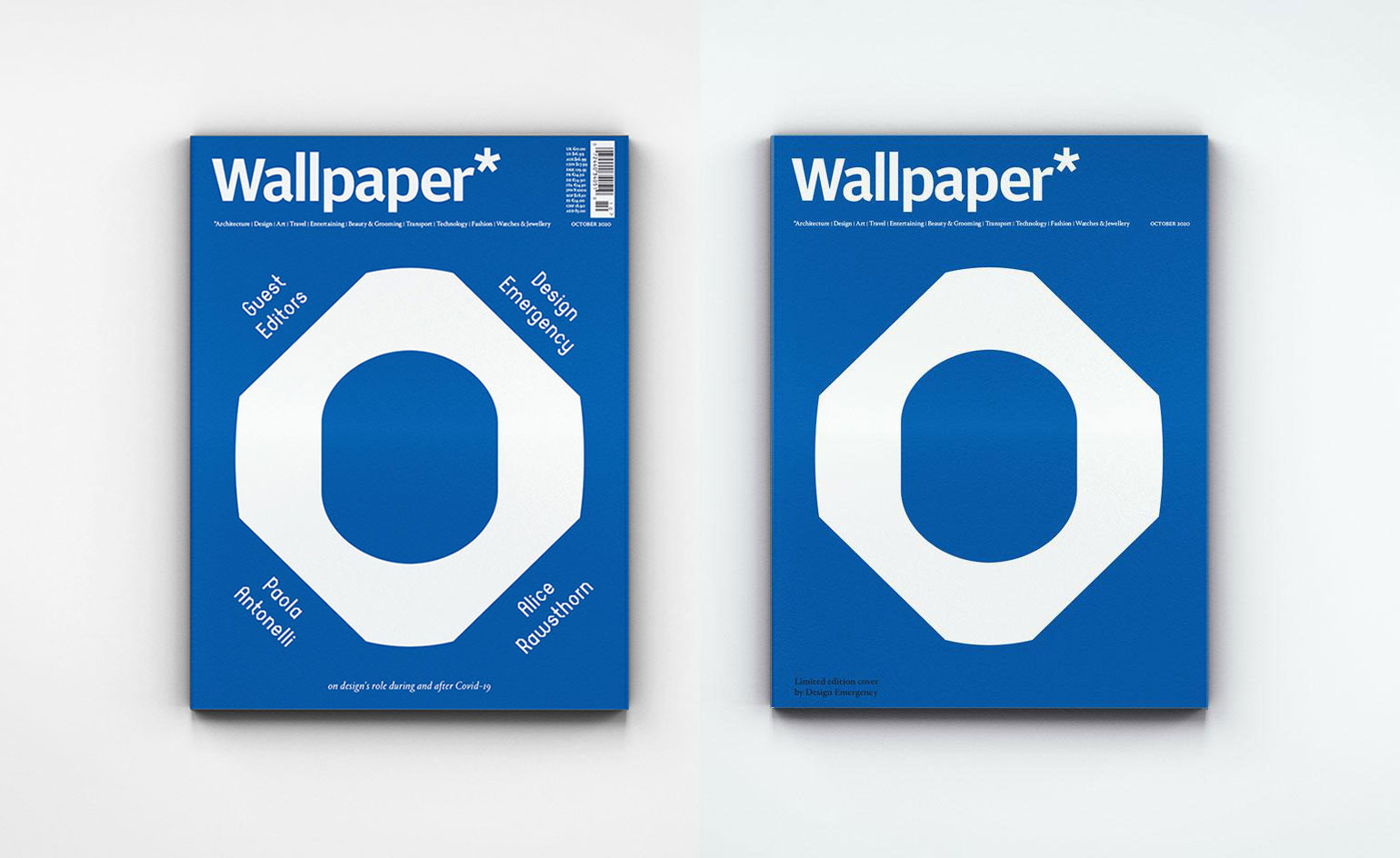

Design Emergency began as an Instagram Live series during the Covid-19 pandemic and is now becoming a wake-up call to the world, and compelling evidence of the power of design to effect radical and far-reaching change. Co-founders Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn took over the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper* – available to download free here – to present stories of design’s new purpose and promise. Here, Paola Antonelli talks to architect Kunlé Adeyemi

Nigerian architect Kunlé Adeyemi’s office – NLÉ, meaning ‘at home’ in Yoruba – is based in two cities built on and from water: Lagos, in the country of his birth, and Amsterdam, the city where Adeyemi settled after a long stint at Rem Koolhaas’ Office for Metropolitan Architecture in Rotterdam. Since its inception in 2010, NLÉ, just like the city of Lagos, has kept expanding, mostly over water, with the architect highlighting the importance of a new practice – more open-ended and versatile, not exclusively imposed from the top down but rather more conversant and recombinant, accepting of informality and of citizens’ imagination. Something we need now more than ever, when we come to regroup, rethink and rebuild after the pandemic. Adeyemi and Paola Antonelli discussed the potential of architecture in helping communities cope with urban density and withstand climate change by acknowledging the power of water.

Paola Antonelli: In 2007, while you were still working at OMA, you published an essay in the journal Log, entitled Urban Crawl. It was an occasion for the western/northern hemisphere to consider cities in developing countries as paragons and paradigms for the future, and also argued for a radical rethinking of the position of architecture.

Kunlé Adeyemi: The article was written shortly after my post-professional degree at Princeton, and I published it with a view in mind. My thesis at the time was on the role of market economies in rapidly emerging cities. I had a lot of reflection around the impact of cities of the Global South and how they would become more important in the future. It was a prompt to rethink our perceptions of cities, understanding that there’s a critical point where cities, just out of the growth of population and economy, begin to become a lot more organic in their expansion, and the nature of the performance of the city – whether economically, socially or environmentally – becomes exponential. That’s what we’re starting to see in several large, growing cities in the Global South. Without infrastructure, or with very minimal infrastructure and very minimally organised economies, they start to regulate themselves, just out of sheer population growth and impact.

PA: In that same essay, you argued that ‘the space of architecture as we know it is getting smaller and smaller’. How do you consider that statement now, 13 years later? Has architecture changed?

KA: I think there’s been a lot of changes in the practice, but not enough change to cope with the speed of development that is necessary to accommodate the growth of human population and the environmental impact of this growth. We’re also losing grip if we do not realise the implication of acting in the capacity of the public realm, as opposed to just providing solutions that are very specific to individuals. In my view, architecture is more of a service, and the client is really more public than private lately. Whatever we do even for private clients has an impact on a larger community.

PA: Would you call that acting in the public realm politics?

KA: For sure. There’s a lot of influence on politics, and political influence on architecture. And I think there are a lot more people that have done more specific work in that realm. In our way of understanding the role of architects or architecture in the built environment, we developed a tool for analysing this sort of urban dynamics, which we call the seven DESIMER Factors. Typically, the architect is trained to think about design as the first solution for addressing any problem, but we would like to analyse the context and the requirements through seven factors – Demographics, Economics, Sociopolitics, Infrastructure, Morphology, Environment, and Resources – that actually drive development. Indeed, politics and social context, even the shape and the topography of the environment are huge factors, and design is only a tool to orchestrate these complex dynamics into built form and to understand programme. Essentially, these factors are divided into two areas of research – issues of humanity and growth, and issues connected to the environment. And that’s what this is for us. Architecture in what we stand for is about diversity and coexistence of humanity and environment.

PA: Are you keeping humans and environment separate because of the agency that humans have over the environment?

KA: Yes. You keep them separate, but you also look at them together. It’s about their coexistence. Whereas as a standard practice we understand people as our clients, but we also at the same time look at the environment as our client.

PA: In 2014, you participated in the MoMA exhibition ‘Uneven Growth’, which looked at the idea of a postcolonial city in which a bottom-up material culture leads and complements a traditional top-down idea of design. What is the role of community in the vision that you have for architecture in the future?

NLÉ’s Makoko Floating School was built for the historic lagoon community of Makoko, in Lagos, Nigeria. Destroyed by a heavy storm in 2016, the prototype led to a series of floating structures, built around the world using a highly engineered flat-pack system. Photography: Iwan Baan

KA: I presented a vision of Lagos in 2050, centred around three points: water, transportation and energy. The image is somewhat our general prototypical vision of what a city that has embraced water looks like. We were beginning to understand the role of climate change and the impact on the environment on our cities. Eighty per cent of our major cities and capitals all around the world are by the waterfront, by oceans, rivers, lakes. Our view is that the development and evolution of humanity are going to become somewhat more aquatic, there will be an increase in that relationship between cities and water. We should learn not to continue to fight it, but learn to live with it.

PA: Are you saying that we will need to expand over water?

KA: There are different conditions, all kinds of very specific site conditions all over the world. We hear a lot about cities that are by the sea or by the ocean, the threat of sea levels rising, the frequent flooding. There are also inland wet areas, wetlands, marshy areas, where groundwater is rising – they need different approaches. We think, generally speaking, that in the real estate that we allocate to the development of cities, the portion that relates to water should increase. We need to accommodate more water basins and have fewer hard surfaces. Even if it’s simply about increasing a drainage system and having more canalisation, that is already an approach to dealing with water and learning to live with it; having more room for capturing rainwater as part of our landscape and urbanscape; actually building on water as a form of habitation, and also reducing land reclamation, which is very, very invasive – it’s expensive, and literally reduces the area of water in a region.

RELATED STORY

PA: Your Makoko Floating School is a famous, and also tragic project. Can you tell us about the community and the school itself please?

KA: Makoko Floating School is a project that began in 2011. I was voluntarily trying to research affordable housing and offering my service to the Lagos State Government. I started to look at what may be considered the cheapest dwellings in a city like Lagos. I realised people who live in Makoko – in what would technically be defined as slums – on water, with very poor quality of construction, were able to build so much out of so little. I got the opportunity to visit the place, and was completely blown away by what I experienced there. There was, of course, a lot of hardship, a lot of environmental challenges but being in the community itself is a totally different experience. One of the community members I met said they would like an extension to an existing school. I thought that if we could improve on their building system, it could be a great collaboration. So we started conceptualising. At some point in the process, we were thinking of building on stilts, like they did. But a few months after we began, there was a huge storm in Lagos, and it occurred to me that a lot of the parts of Lagos that were on land were actually going to be flooded. It is a very vulnerable environment for a very large city of nearly 20 million people. Even though people in Makoko were building on water, they were still affected by the tidal change, so we developed the floating solution that adapted to the tide.

PA: In 2016, however, a seasonal storm destroyed the school. What did you learn from it?

KA: There’s a misrepresentation and misunderstanding of the situation surrounding the collapse, especially from the public realm. A lot of people considered it a disaster, a tragedy, maybe out of our control, but it wasn’t that, and we have a full report on our website about the circumstances that led to it. The building was a test, it was a prototype. We had worked on it with the community and we saw it coming to its end. It was not literally brought down just by the storm; we had had many storms in the past. What we learned is to be completely relentless in innovation, and innovating means understanding that failure is also part of the learning curve.

PA: Indeed, you transformed the experience into an evolving construction system. It had different prototypes, shown at the Biennale in Venice, in Bruges (Belgium), in Minjiang (China), and the latest one is in Cape Verde.

KA: We’ve evolved Makoko Floating School into what we call Makoko Floating System, which is really a simple way to build on water by hand. We learned from the people of Makoko and then improved the process into a flat-pack system, prefabricated, easy to assemble, disassemble, highly engineered to European codes, which you can apply internationally. We’ve built it in five countries across three continents, tested it in different environments, tested it with different local materials, looked at the collaboration, understood different contexts and how it would adapt in its different variations and uses.In Bruges, we had some covering with panels, and it was used as a school. In China, we had bamboo. In Mindelo in Cape Verde it’s a floating music hub. It’s in the ocean now. We’ve made a lot of improvements to what started out as a handcrafted, guerrilla-style project. And I want to mention that while it was a school – an incidental use at the time – the project was actually funded and supported by the United Nations Development Programme under the Climate Change Adaptation programme. So it’s always been a project about climate change adaptation, about response to the environment, and the school was an example of the use of it.

PA: A very inspiring example, however, because it was in such a creatively energetic community.

KA: The community is the origin and the key, and the source of the potential of using the system as a way to develop a much improved quality of life for the poor or the rich, it cuts across social classes. It’s about local materials. It’s about local responsibility, understanding what is within means, and maximising it. So that’s where we’re at now, where you can use the system for housing, a resort, a library, all kinds of facilities – on water.

PA: What has the Covid-19 crisis taught you?

KA: There has been the opportunity to step back a bit, slow down, re-evaluate what is important, understand, try to be more efficient, connect with family, change my diet [laughs]. So it’s been a great time to be reflective, as with most people, but also to try to develop the focus on what we think would be important.

PA: Your research right now is about African cities and water.

KA: Water cities as a body of work for the last nine years, since we began Makoko Floating School. We immediately saw the potential, both globally and also for the African continent. I’ve continued the research at the various institutions where I’ve taught. We took students to different cities: Durban with Harvard, Abidjan with Columbia, Lagos with Cornell, and we looked at Mindelo with Princeton. There’s a whole world. A lot of African cities that we’ve been focusing on are on water – the African Water Cities Project. The students are looking at different approaches to tackle the urgent challenges we’ve identified from the research – the adaptation of cities to the changing climate.

INFORMATION

A version of this story appeared in the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper*, guest edited by Design Emergency. A free PDF download of the issue is available here.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.