Gambit elevates the metal tube in this Polish HQ's 'surprising solution’

A Katowice-based architecture studio creates Gambit, a whimsical head office for a Polish plastic piping distributor

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Inventive architecture can be found in the most unheralded locations. If you are heading west out of the historic Polish city of Krakow, and happen to find yourself in the industrial city of Gliwice, you should check out a building that is disguised as a stack of pipes, with a profile that evokes an ancient Egyptian tomb.

It was commissioned by Gambit Systems, which distributes the heavy-duty plastic piping of Swiss firm Georg Fischer. The company wanted a distinctive head office and warehouse, strategically located close to several major highways, and this was the brief it set to architecture studio KWK Promes, in the nearby city of Katowice.

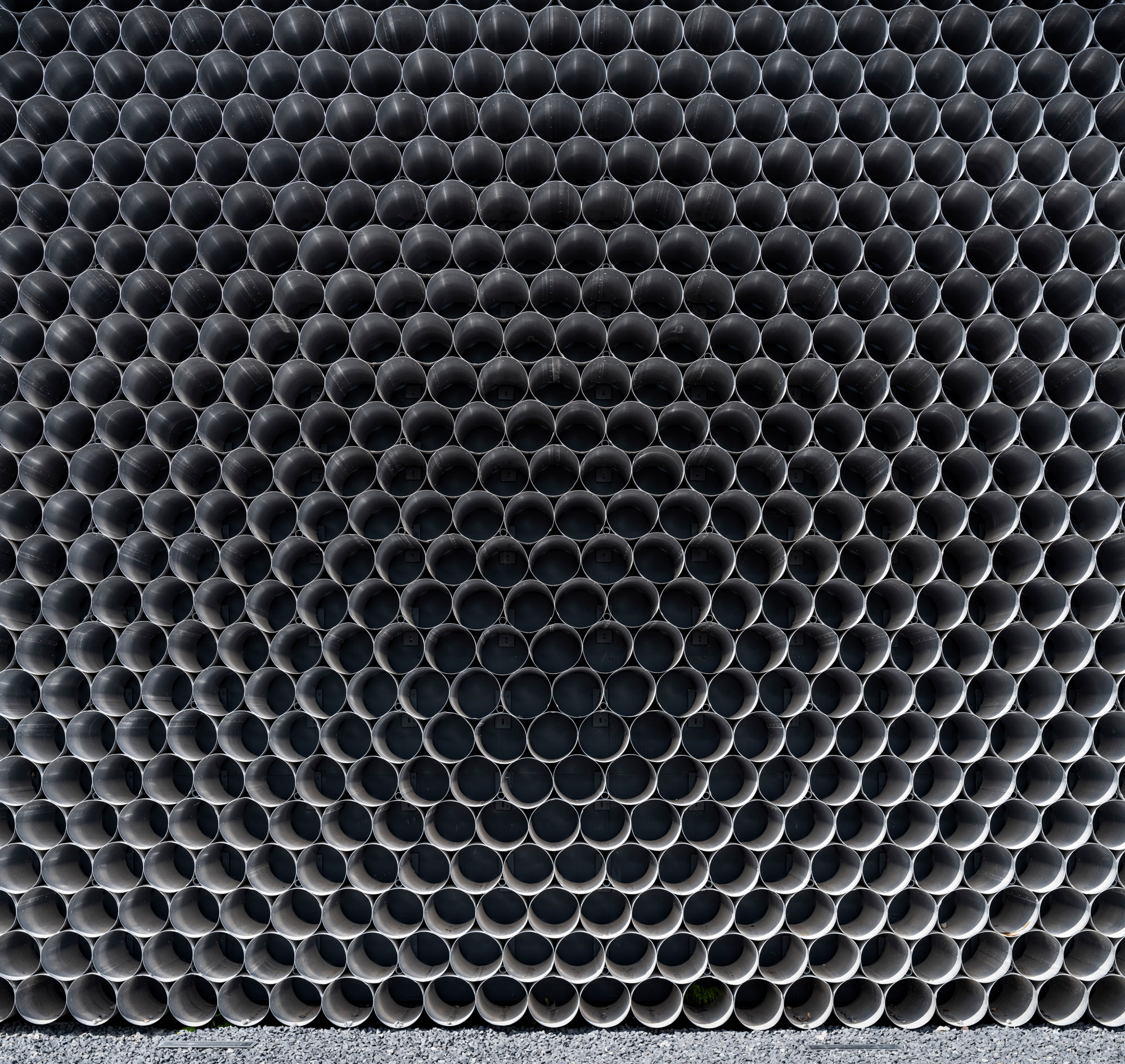

Echoing the PVC piping that Gambit distributes, a metal fabrication company created a series of aluminium tubes, which were welded together and riveted to a frame

Gambit: ‘The power of logic can sometimes lead to fresh, even surprising solutions’

Robert Konieczny, who founded KWK in 1999, describes himself as a conceptualist, looking for a defining idea at the start of every project. ‘We take a path, stick to it, and reject all unnecessary elements,’ he writes in a just-published monograph comprising 19 of his firm’s buildings. ‘Every step of the design must have an explanation,’ he says. ‘The power of logic can sometimes lead to fresh, even surprising solutions.’

Konieczny’s bold approach has produced auto-friendly homes that allow you to drive a non-polluting car inside; a house with a grassy floor that opens up to a garden on every side; and a project in Saudi Arabia in which a glass cylinder frames desert views, and which is protected by a shade that rotates with the sun. In the Czech city of Ostrava, KWK transformed a ruined slaughterhouse into the Plato Contemporary Art Gallery, inserting massive pivoting doors to fill gaps in the masonry and open the interior to public view. It is one of seven finalists up for the 2024 EU mies Prize.

Gambit respects the modest scale of houses that border its industrial zone of warehouses and mineshafts (an area recalling the years when Silesia was a centre of coal production). The building comprises three sections: a double-height storage block linked to a two-storey office/showroom by a low workshop in which orders are prepared for shipment.

The offices have the profile of a mastaba, a truncated pyramid of mud blocks in which the nobility of ancient Egypt were buried. Artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude proposed a huge mastaba of multicoloured oil drums for Abu Dhabi in 1977, and realised the concept in London in 2018. Here, it plays off the pitched slate roofs of neighbouring houses and produces a shape that appears to shift subtly as you move around it.

KWK’s initial concept was to envelope the reinforced concrete building with lengths of the piping that Gambit distributes: a solution that would be simple, fast and cost-effective. The client could supply the elements from its own inventory and use its expertise to assemble them. The result: architecture parlante, a building that advertises the product it sells.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour would have called it a ‘duck’ (a building that expresses its function through its form, a concept they first established in their book Learning from Las Vegas in 1972), in contrast to the painted sheds that most industrial firms settle for. However, KWK quickly realised that the PVC piping, designed for use underground, was too heavy, flammable and vulnerable to UV rays to be acceptable as a cladding material.

Instead, it invited a metal fabrication company to shape thin, inexpensive aluminium sheeting into sections of tubing, ranging in length from 50-150cm. The shorter sections would cover the end walls, while the longer ones would be welded together and riveted to a frame along the sides and sloping roof. It was hard to achieve the level of precision required for a perfect fit, working on a very tight budget, but the builders rose to the challenge.

To provide good insulation for the work spaces and unheated storage areas, the side walls include a layer of glass as a waterproof membrane and a thick layer of insulation between the pipes and the concrete. The office block incorporates a ground-floor showroom and upstairs meeting rooms that open onto a central roof terrace. Geothermal wells and a heat pump cover most power needs, even in the frigid winters of Silesia.

By using a commonplace element in such an expressive way, KWK has elevated the humble metal tube in one fell swoop. And, as Konieczny acknowledges, the idea just came to him as he walked through the warehouse with its shelves of stacked pipes.

‘Robert Konieczny, KWK Promes: Buildings + Ideas’, £50, by Robert Konieczny, edited by Philip Jodidio, is available from Images Publishing

A version of this article appears in the May 2024 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Michael Webb Hon. AIA/LA has authored 30 books on architecture and design, most recently California Houses: Creativity in Context; Architects’ Houses; and Building Community: New Apartment Architecture, while editing and contributing essays to a score of monographs. He is also a regular contributor to leading journals in the United States, Asia and Europe. Growing up in London, he was an editor at The Times and Country Life, before moving to the US, where he directed film programmes for the American Film Institute and curated a Smithsonian exhibition on the history of the American cinema. He now lives in Los Angeles in the Richard Neutra apartment that was once home to Charles and Ray Eames.