Modernist Coromandel farmhouse refreshed by Frankie Pappas, Mayat Hart and Thomashoff+Partner

An iconic Coromandel farmhouse is being reimagined by the South African architectural collaborative of Frankie Pappas, Mayat Hart and Thomashoff+Partner

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Coromandel House is the centrepiece of a vast stretch of farmland set between Lydenberg and Dullstroom in Mpumalanga province, about three hours’ drive from Johannesburg. Designed by Marco Zanuso in 1969 and completed in 1975, it is a now a pilgrimage site for young South African architects, a pioneering study in ‘passive’ design and skilfully setting a house – a very big house – in nature; welcome to the celebrated, modernist Coromandel farmhouse.

The estate, a composite of what were 24 smaller farms, was established by the South African retail entrepreneur and husbandry innovator Sydney Press, who hoped it would become a benchmark for agricultural excellence in the country. Press wanted to build a comfortable part-time pile at Coromandel. His wife Victoria, a New York-born fashion designer and a keen follower of contemporary architecture, spotted a set of twin Zanuso-designed rural retreats in Sardinia, and suggested he was the man for the job.

Coromandel farmhouse by Marco Zanuso

Zanuso was already an established giant of post-war Italian design. The arch-modernist’s best-known architecture, factories for Olivetti in South America and offices for IBM in Milan, were exercises in large-scale rationalism. The Sardinian houses, though, were small, low-slung fortresses, built in local stone and seeming to emerge out of the rock. The couple asked Zanuso to build something along the same lines but bigger for the Coromandel farmhouse.

Zanuso brought over his own team of Italian collaborators to realise his vision, including landscape architect Pietro Porcinai and designer Livio Castiglioni. The result is single-storey and squat with metre-thick concrete walls clad in brown local stone, edging towards a kind of arcadian brutalist architecture. The interiors are similarly rustic-modern, all stone cladding and indigenous wood, though Zanuso, always a champion of new technology, added electric sliding doors. (He also created custom furniture for the house, though little of that remains).

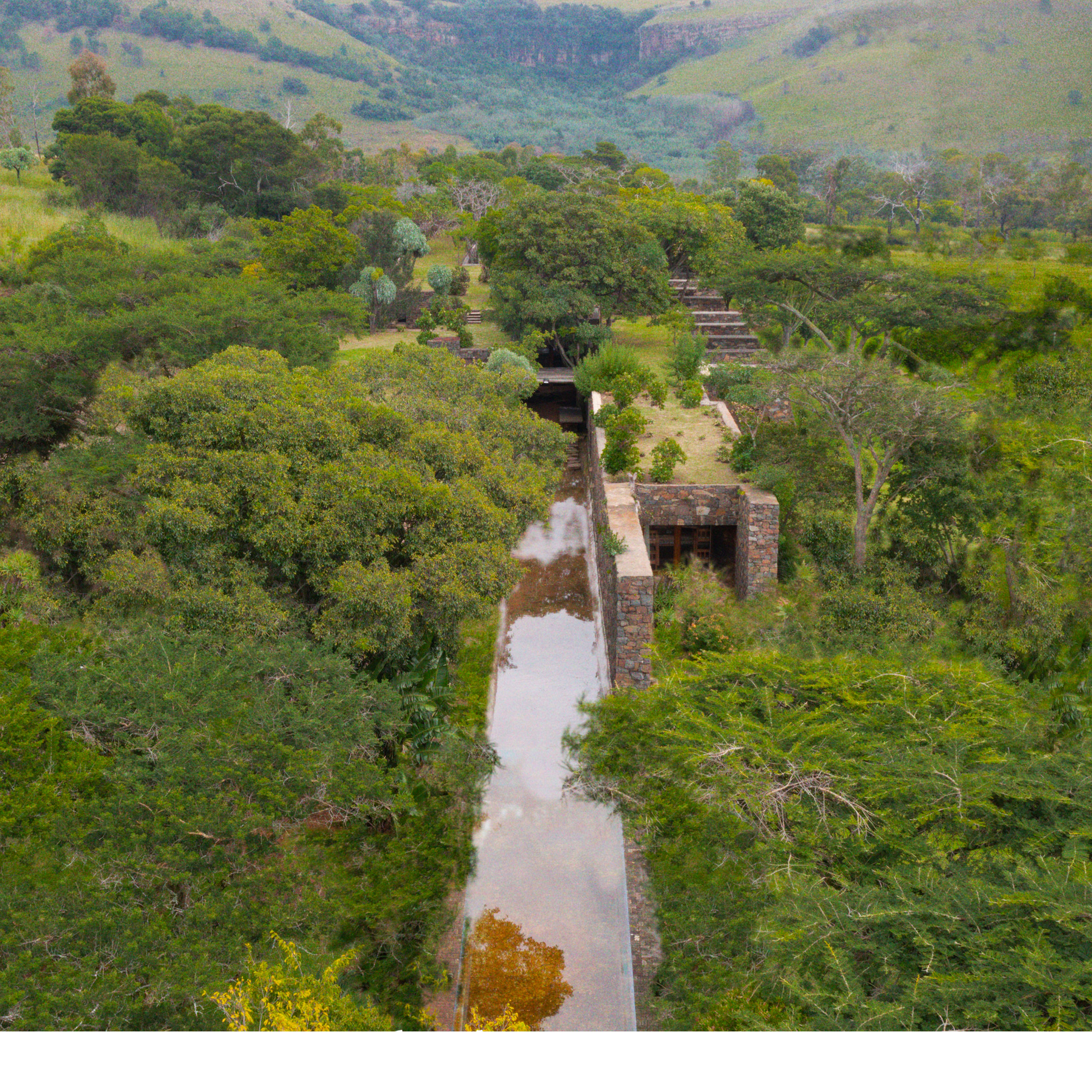

What really defines the building, though, is its long, thin plan. The house is 240m long in total with a central communal hub and four wings set along two 4m-wide courtyards, one filled with water leading to a swimming pool, and designed to reference local rivers and ‘kloofs’ or ravines.

Edna Peres, a specialist in regenerative design and co-author with Andrea Zamboni of the new book Creating Coromandel: Marco Zanuso in South Africa, explains that Sydney Press often compared the house to a small Italian town with shaded narrow streets leading off a public piazza.

The Coromandel farmhouse’s indoor piazza, its central communal hub, included an entertainment space, solarium, kitchen, dining room and lounge with views over the rolling landscape. Along the ‘streets’ were two children’s wings (the Presses had seven children), the main bedroom suite and a service wing.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

It was crucial for the couple that the house be at one with the veld, so sensitive landscaping was crucial. After Porcinai’s departure from the project, they turned to a young South African landscape architect, Patrick Watson, who collected and propagated local plants, and created a remarkable roof garden and planted local sand figs, now rooted to dramatic effect in the stonework. (Watson introduced the couple to Roberto Burle Marx, who came up with designs for a garden. The Brazilian’s proposals, though, proved too conceptual, formal and insensitive to local flora and fauna for their liking).

Sydney Press’ years of stewardship on the estate ended with his death in 1997 and its sale in 2002. The hardly used house now resembles a hidden Star Wars temple or hunkering rebel HQ, complete with strange flying buttresses that serve no obvious structural purpose.

Now owned by the Coromandel Farmworkers Trust, the estate has struggled without Press’ considerable financial and strategic backing. It is, though, a major draw for nature lovers as well as architectural pilgrims. The 14,000-acre estate boasts mountains, spectacular waterfalls and a nature reserve, and offers opportunities for trout fishing, hiking and mountain biking. Suzanne Press, Sydney and Victoria’s daughter and an art conservator based in London, is now set on amping up that appeal to tourists and bringing new life to the architectural treasure that is Coromandel House and allowing more guests to enjoy an updated version of its original ‘getaway’ intention.

The future of Coromandel farmhouse

Knowing of her interest and research into Coromandel, Suzanne Press contacted Edna Peres for advice on the restoration project and together they contacted Andrea Zamboni of Zamboni Associati Architettura. In discussions with investors and operators, a captivating architectural vision became essential. Edna suggested contacting local architectural firms who had helped with research for Creating Coromandel. A collaborative team was formed including Frankie Pappas, Mayat Hart and Thomashoff+Partner.

Ant Vervoort, one of the founding members of the Johannesburg-based architecture and design collective Frankie Pappas, is one of the building's admirers. The practice's Big Arch house, in its long, slim plan, material choices and mission to become part of the landscape (see the studio's entry in the Wallpaper* Architects Directory 2020), owes a clear and acknowledged debt to Zanuso's design.

Recalls Vervoort, 'Edna got in touch with me and said, “I’ve seen House of the Big Arch, you must know Coromandel. What's the story?” (Vervoort’s relationship with the Coromandel farmhouse pre-dates, or perhaps helped spark, his interest in architecture. His father, a ‘pig consultant’ as Vervoort junior puts it, took his young son along on reconnaissance trips to the estate.)

The architectural team have adopted a minimum change for maximum yield approach – a 'heritage’ strategy in which Thomashoff and Mayat Hart specialise – to safeguard the architectural gem. (Any building over 60 years old gets a heritage classification and some measure of protection in South Africa. The Coromandel house doesn’t yet qualify but Press is determined that it will survive long enough to earn that status.)

The team have set on sensitively reimagining the house’s four wings into six independent suites with access through the courtyards. They are also planning to add a new external staircase (proposed by Zanuso but never built) leading to private roof terraces. They are also set on making the house fully off-grid, with on-site solar panels and water re-use.

The building is in remarkably good condition and the plan is to leave the fundamentals of the house and its landscaping largely untouched. ‘We want to keep the bones and reduce the intervention,’ Vervoort says. 'It’s really about reducing energy requirements and getting the spaces to work and feel comfortable so they can be used for the next 50 or 60 years.’