The C40 World Mayors Summit flags Copenhagen as one of the greenest cities in Europe

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

When it comes to climate change and sustainable architecture, Copenhagen isn’t messing around. Before you even touch down at the airport, a cluster of offshore wind turbines swirl their steely arms – a jubilant welcome, but also a guilt-ridden reminder that you’re arriving into the world’s greenest city, by plane.

The C40 World Mayors Summit 2019 is now in full swing. The global network of metro-chiefs is gathering in Copenhagen to discuss all things climate change, compare notes and root out the guiltiest fossil fuel guzzlers. C40, which organises the summit every three years in one of the 96-member cities, are now working towards the Women4climate conference in Sydney next April, celebrating women at the forefront of climate action.

Before the ink on the 2016 Paris Agreement was dry, this once smoggy industrial city had already hit the ground running, cycling and recycling its way to earning carbon neutral status by 2025. ‘Many of my [mayoral] colleagues use Copenhagen as a benchmark because we have this plan to be carbon neutral by 2025, and we have a lot of concrete solutions for sustainability,’ explains Copenhagen’s mayor, Frank Jensen.

The summit though is a chance for Jensen to share as much as gloat. ‘We can often talk about stealing ideas from each other, but it is legal to steal ideas from people in C40,’ he explains. ‘You have to be very active to become a member of the C40. You have to deliver and cannot be a sleeping partner. If you’re a sleeping partner, you’re thrown out of the organisation.’

Copenhagen has certainly not been sleeping. Since 2005, it has managed to cut emissions by 42 per cent by snubbing fossil fuels and backing more sustainable means of transport, developing Wilkinson Eyre’s sleek inner harbour bridge, dedicated to cyclists and pedestrians, and the city’s ‘environmentally sensible’ and design-minded metro line, led by Arup Architects and unveiled this September.

We travelled to Denmark to explore a few of the many ways the city is addressing climate issues and envisaging a cleaner, greener way of global living.

Copenhill / Amager Bakke

As rubbish burners go, the Amager Resource Center (AKA Copenhill) is not a run-of-the-mill square-blocked eyesore. The long-anticipated project, which has just opened its roof, deploys Bjarke Ingels Group’s ‘hedonistic sustainability’ with an artificial ski slope, recreational hiking area and climbing wall on top of the waste-to-energy plant. ‘It’s a very good idea and a crazy idea to build a ski slope on a furnace,’ says the plant’s CEO Jacob Hartvig Simonsen. ‘We have provided a safe facility for them to play on.’

The building’s façade is comprised of cool clean aluminium blocks stacked up like Jenga. The 450m ski slope, in an apt shade of green, snakes down the structure with a 180 degree twist to the bottom, while a ski shop and après ski bar add an air of authenticity to a snowless slope and mountain-deprived vista. An enormous chimney emits ‘smoke rings’ (not actual smoke, don’t panic) of water vapour each time 250 kilograms of carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere.

The plant itself opened in 2017 and aims to treat 400,000 tonnes of waste annually. It already supplies 150,000 Danish households with district heating and 70,000 with electricity from non-recyclable waste. The only hiccup is there might not be enough local waste to keep its fires burning. Fortunately, neighbouring countries have bounteous trash at their disposal. Last year, the plant imported and processed around 80,000 tonnes of waste from Great Britain previously destined for landfill. Copenhill might be the ticket to giving waste disposal some much-needed airtime. copenhill.dk

Østergro

In a tucked-away corner of the ‘climate change adapted' district of Østerbro is large spiral staircase. It leads to the Eden of all city farms, Østergro. On the roof of a former car auction house you’ll find 600 sq m of organic vegetables, herbs, edible flowers, beehives and a coop of clucking hens. Nothing feels too preened, and you wouldn’t want it to be.

In a world where we’ve almost severed ties with the roots of our food, Østergro also serves as a platform for agricultural education, giving visitors a crash course in food production and the value of sustainable eating. The farm’s restaurant, Gro Spiseri serves a biodynamic mix of sharing plates, using seasonal ingredients from local farms and Østergro’s own produce, dished up from stem to bowl. The menu – omnivorous, but heavily weighted on plant-based foods – is executed with skill and grace by a close-knit team of chefs, some of whom have the kitchens of Noma, 108 and Manfreds on their CVs.

Picture celeriac noodles, Danish octopus with fermented garlic mayonnaise, forest berry compote with beeswax. And never underestimate what a beetroot and chocoate mousse, washed down with organic wine, can do to your palate. Østergro leaves you permenantly on the edge of your tastebuds and proves there’s still joy in growing your own. oestergro.dk

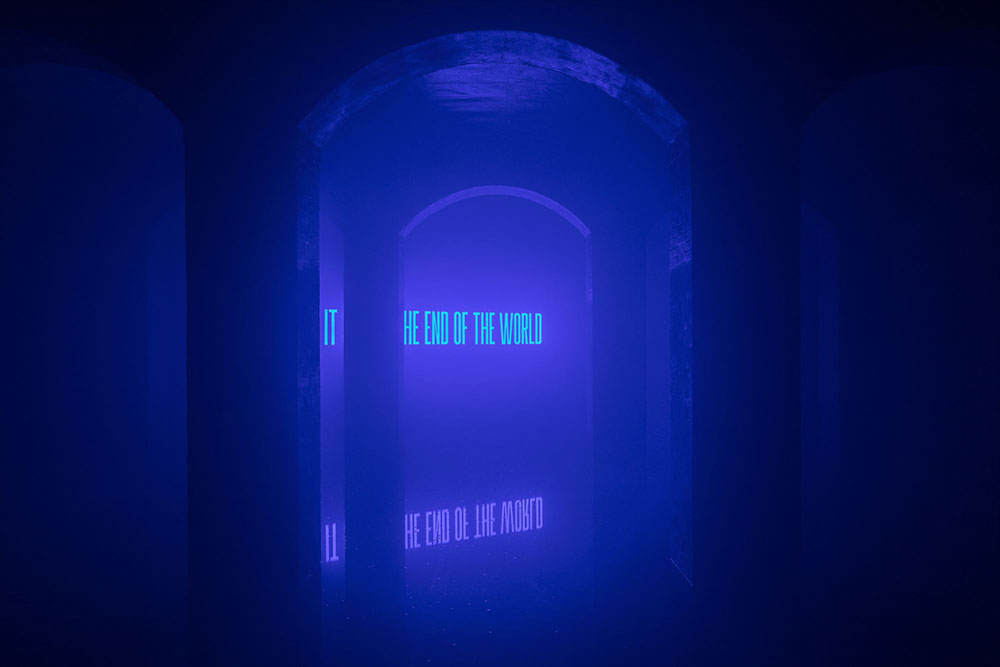

It's not the end of the world

The eerie depths of Cisternerne, a subterranean reservoir turned art exhibition space look somewhere between a cathedral crypt and The Chamber of Secrets. Since Danish art collective Superflex (comprised of Jakob Fenger, Rasmus Nielsen and Bjørnstjerne Christiansen) got their hands on it earlier this year, it’s stood for the dingy, damp, squalid end of humanity.

Their exhibition takes a dystopian stance on issues of climate. The cistern has been flooded in a foot of water. Dare to edge deeper though the water and into almost complete darkness, and something very bright and very blue cuts through the gloom. ‘It is not the end of the world’, reads a pulsating neon sign. Perhaps a declaration of hope, or a warning that if we continue our self-destructive behavior, the world will go on, with or without us.

This scenario might feel tricky to imagine, but Copenhagen had a taste of this in 2011 when six inches of rainfall in three hours deluged the city and caused six billion Danish Kroner in damage. In the same year, the city developed its Climate Adaption Plan to prevent the impact of extreme climate shifts. The exhibition, which runs until 30 November, might leave you with lingering insecurity, but a few things are certain: you’ll need a pair of wellies (which are provided), a robust disposition and an open mind. cisternerne.dk

Nordhavn

Scandinavia’s most ambitious urban regeneration project to date, Nordhavn (The North Harbour) is cementing itself as a district built on social cohesion. In recent history, it was a mucky, industrial borough rife with cruise ships and bustling with port container logjam. The industrial activity lives on, but this time it’s all in the name of sustainability, led by agency By og Havn and Cobe architects.

The vision is carbon neutral, harnessed through rainwater recycling, solar power and clever use of the grid. Nordhavn is a smorgasbord of architectural approaches. In this urban archipelago, streets are fragmented by man made canals, which punctuate a network of islets and keep the region at one with its marine roots. It’s just as much about retrofitting older buildings as wiping the slate clean with new builds.

Design Group Architects has managed to make a pair of ex-silos look sexy. The Portland towers were originally constructed to store cement and are now gleaming beacons of architectural rejuvenation, with 360-degree views. Lüders, a rusty-red building designed by Jaja Architects takes its multipurpose concept to great heights with a supermarket, electric car recharging facilities and a large recycling station. A zigzagged exterior staircase has a built-in timer for workouts, and the 2,400 sq m urban roof hosts a large playground, training facilities and panoramic harbour views.

Meanwhile, UN City is a striking harbour-side building designed by 3XN as the United Nations’ regional head office. The fragmented, star-shaped structure has 1,400 rooftop solar panels, significantly reducing the need for grid resources. This district is the embodiment of Copenhagen’s climate change goals and might have set the bar for what’s possible and essential in city planning. byoghavn.dk

The Østergro rooftop garden, located above a former car auction house, features 600 sq m of farmable resources including various vegetables, plants and flowers

Superflex’s reflective ‘It is not the end of the world’ occupies the subterranean art exhibition space Cisternerne, and can be read as a declaration of hope or a warning to curb our self-destructive tendencies.

An aerial view of Nordhavn. At the centre, find the Portland towers which were renovated from former silos, and, right, 3XN’s UN City.

INFORMATION

The C40 World Mayors Summit runs until 13 October. c40.org

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.