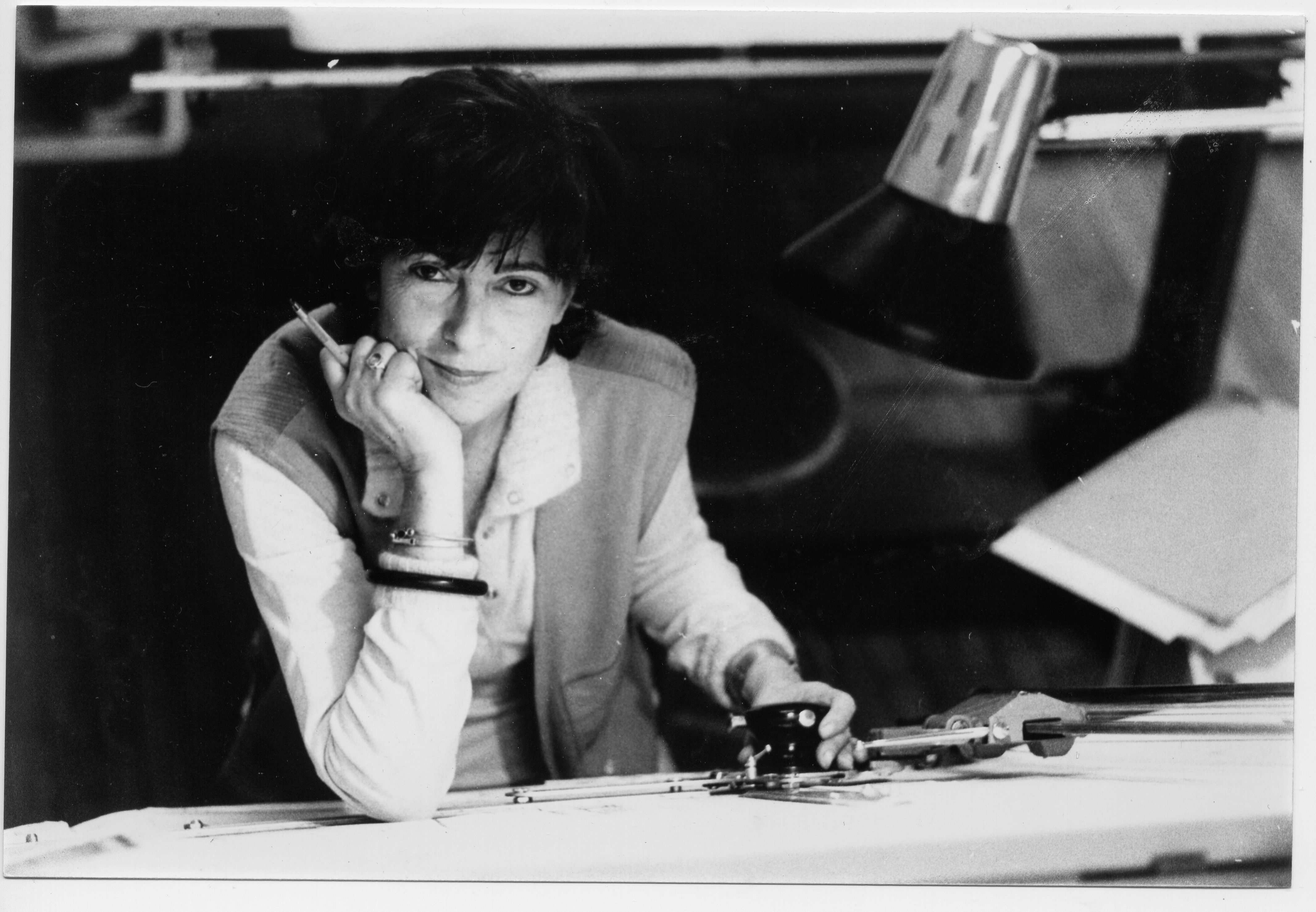

In memoriam: Cini Boeri (1924 - 2020)

The Italian architect and designer Cini Boeri championed economy and functionalism as a philosophy to make the world a better place

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Cini Boeri (1924 - September 9 2020), born Maria Cristina Mariani Dameno, was an Italian architect and designer known for her interest in functionalism and economy. She believed that beauty was the result of function and only took pleasure from adding useful, long-lasting architecture and design to the world. For her, the purpose of these objects, buildings and spaces, was to help people and make them happy.

Boeri graduated from Milan Polytechnic in 1951, alongside just two other female graduates. She took an internship at Gio Ponti's studio, before working for Marco Zanuso across architecture and industrial design until 1963, when she would set up her own studio, Cini Boeri Architetti.

Her interest in industrial design and economy – at every stage from materials, to technology and manufacture – perhaps grew from her experience growing up during World War II. As a daughter to staunchly anti-fascist parents, at just 18 years old she was couriering important documents across the country for the opposition, and even sewed herself a skirt out of parachute material.

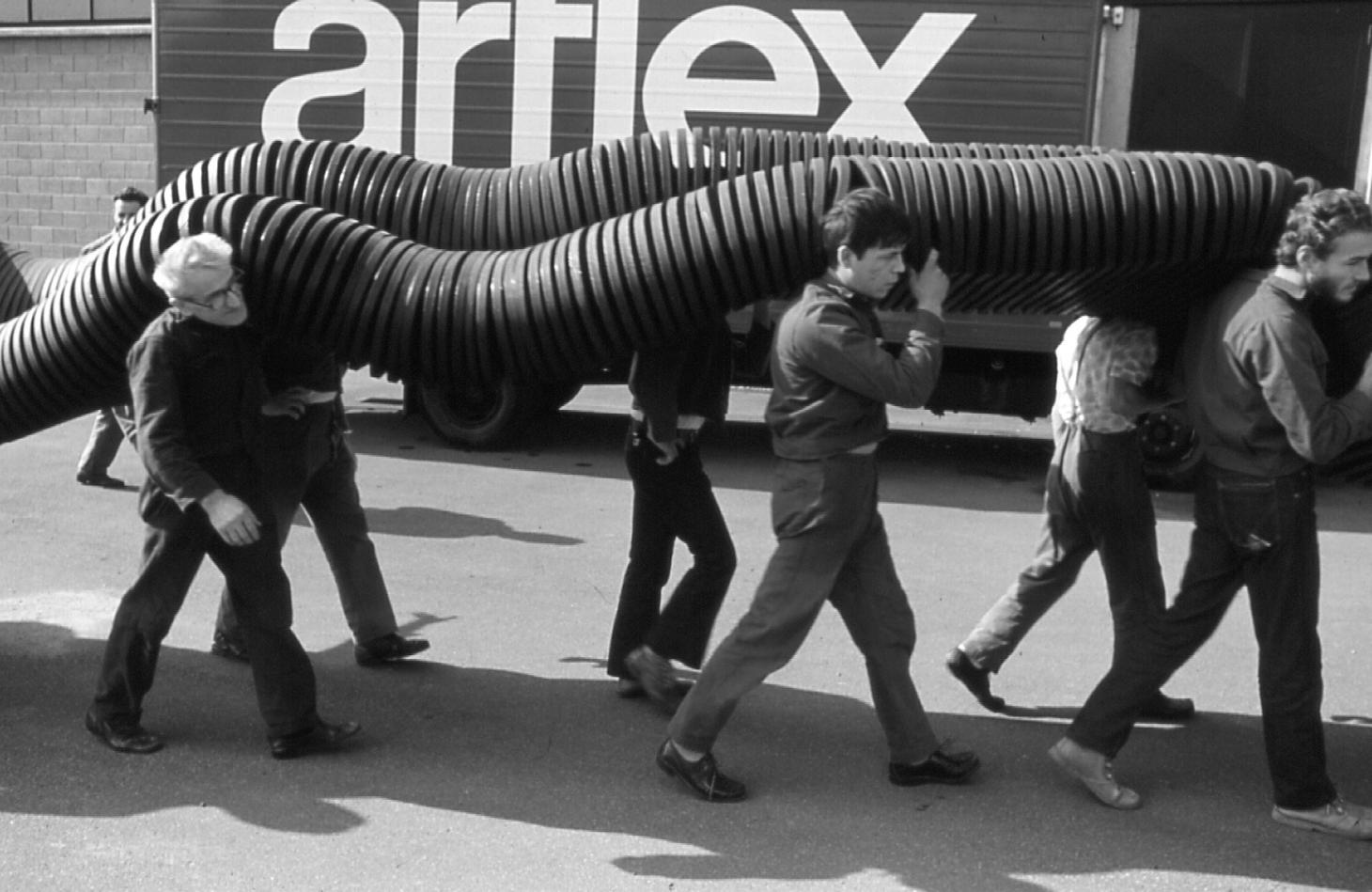

Cini Boeri's Serpentone Sofa at Arflex's factory

Many of her designs were modular or used a very limited palette of materials, and often strictly a single material. The Serpentone sofa designed for Arflex in 1971 was made only of polyurethane foam and it was sold by the metre – so the continuinously snaking sofa could fit and mould to the proportions of any space. In 1972, also for Arflex, this thinking was evolved into a more traditional system of armchairs, beds, sofas, and poufs in the Strips system, also frameless and made entriely of polyurethan foam, which won a Compasso d'Oro.

Elegance was always the product of Boeri's economy. This can be seen particularly in the Lunario table series of 1970 produced by Gavina, where Boeri was a contributing designer, and distributed by Knoll. The marketing images show the oval glass table tops of various sizes echoing each other like ripples of water or light – in their simplicity, the tables echo the elements essential to our human existence.

Knoll acquired Gavina in 1968, and a long relationship between Knoll and Boeri followed. She further developed her expression as a designer with Knoll, notably with the Brigadier sofa, 1978, which somewhat departed from her earlier work, with its rigid panels and high-gloss colours. Throughout the 70s, Boeri designed Knoll showrooms in France, Germany, Italy and California, and later in 2008, returned to design the Cini Boeri Lounge Collection.

There was a severeness to the challenges Boeri set herself, and ultimately her commitment to her ideals was what formed her most iconic pieces. The Ghost chair of 1987, made for FIAM, was designed out of a single 12mm thick glass sheet. The resulting form readdresses our perceptions of the material, glass; how we define comfort; and the limits of design technology and engineering. It was a mastery of economy – certainly raw, yet also pure, and beautiful. The Ghost chair was an evolution of more conceptual experiments in rawness, seen in earlier pieces such as the Mod. 602 Table Light made of PVC industrial tubes for Arteluce in 1968.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

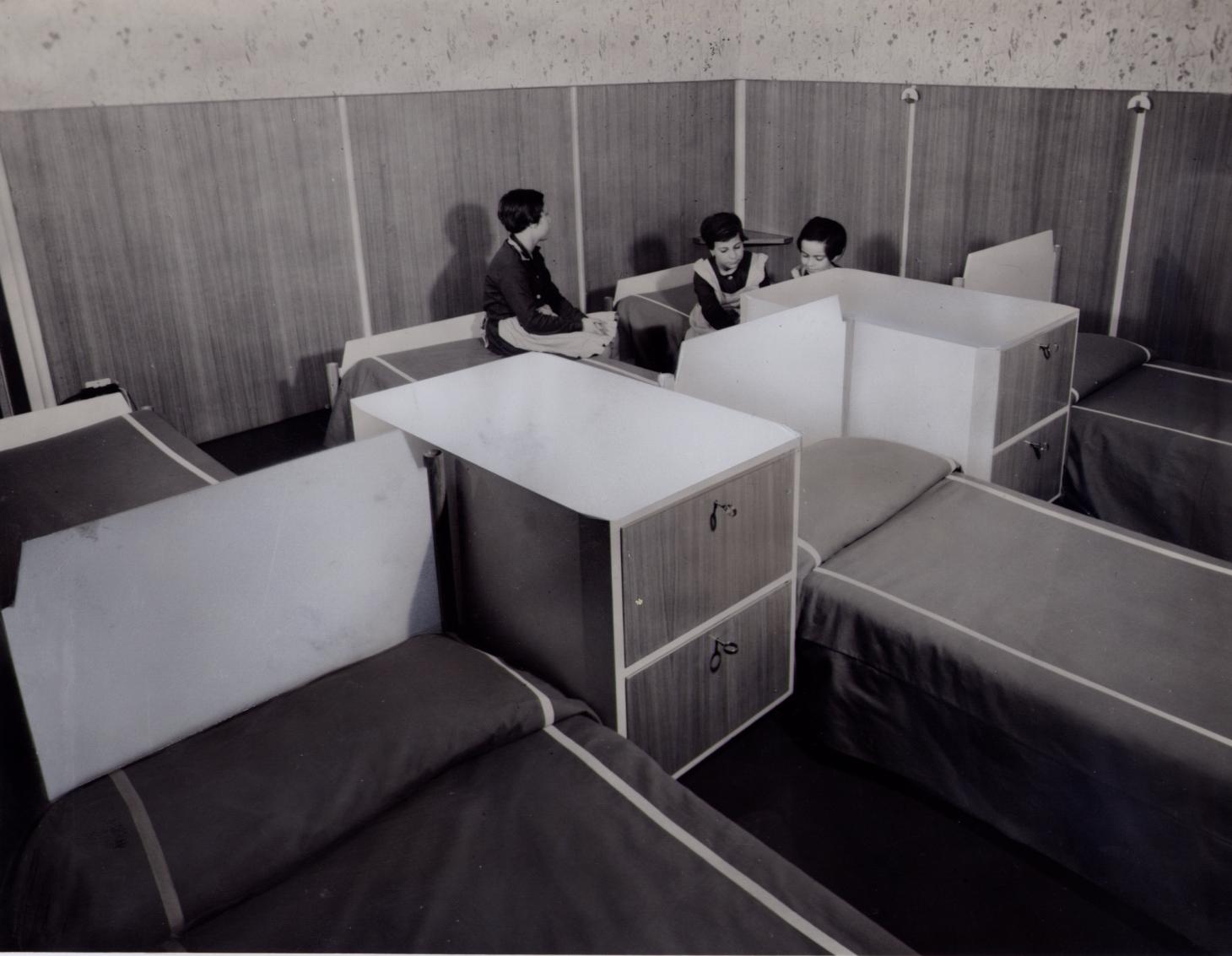

Understanding practicality and productivity as a young woman, perhaps allowed her to succeed in a society that often discounted the usefulness of women in male dominated jobs such as architecture. When working for Zanuso, Boeri designed the interior of a refuge for single mothers in the Lorenteggio neighbourhood of Milan. Her design provided a bed, with storage and a simple partition wall. It pushed economy to the limits, yet rightly so; it took on the heavy responsibility of balancing human needs, with freedom, essentially.

Each inch of better-designed space could open up more space for another woman in need. The value of that space – which meant independence and even survival – was so high. When the stakes are so high, what is the minimum amount of space and services that we need as humans, to continue to feel human? This is the type of question that kept Boeri's feet firmly on the ground.

The interiors of Milan's Istituto delle Carline, a refuge for single mothers for which Boeri designed the interiors and furniture

Perhaps because Boeri herself lead a very independent life as a woman for her time, she understood how design and architecture could truly help or hinder people's lives. She brought up her three children, whilst continuing to work and contribute to design and architecture. She saw the task of her discipline as physically supporting life.

This ‘psychological’ approach to architecture could be seen across her architectural designs, which spanned houses, offices, retail spaces and exhibition design. There was always an interest in flexibility – she always had the future in sight, and even envisioned an age where people would be working from home more often; the tension between communal and private space; and the project’s relationship to its environment and context. Casa Bunker, 1967, and Villa Rotonda, 1969, both in Sardinia, very much respond to their coastal setting, enveloping and protecting the inhabitants, whilst also opening up space for them to live inside the landscape.

Boeri read people and faces, just as thoughtfully as she would read a design brief, and this skill made her a keen communicator. She taught classes and spoke at conferences internationally. Between 1981 and 1983 she taught architectural design and industrial and interior design at Milan Polytechnic, where her son Stefano would later study architecture and go on to international acclaim.

She contributed widely to the cultural conversation. Many of her published essays were concerned with domestic design and architecture. She joined the board of directors for the XVI Milan Triennale, and participated in the exhibition titled Domestic Project at the XVII Milan Triennale in 1986.

For Boeri, architecture and design was an ethical undertaking. It was always a huge responsibility, rooted in a quest for dignity and a belief in equality. Boeri is survived by her three sons, Stefano, Sandro, and Tito.

INFORMATION

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.