Cherem Arquitectos creates a concrete landmark in the Mexico City suburb of Bosque Real

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Having felt tremors while staying at Hotel Downtown in Mexico City (winner of Wallpaper's 2012 Design Award for 'best fixer-upper hotel)', the first question I asked its creator, architect Abraham Cherem, was how earthquake-proof it is? 'Downtown is a seventeenth century palacio in Centro Histórico where the soil is unstable,' Cherem begins. 'Three feet underground you hit water, so earthquakes in this area are stronger. It's a listed building, so we had to consider how and where to strengthen the building without damaging it. It was a tough challenge,' he adds.

Given how often the 'earth yawns' (as locals say), it's a miracle the 500-year-old Centro Histórico stands at all. Perceived wisdom declares that these ancient buildings know how to 'move' with the earth. 'The way they built back then was so clever,' says Cherem. 'They thought about longevity and used natural materials that can last forever. They thought about climate, so the walls are very, very thick.'

Cherem may have had history on his side with Hotel Downtown, but his most recent house, built in collaboration with Rodolfo Diaz, was built from scratch. Created for a famous Mexican footballer, it's a concrete landmark in the gated suburb of Bosque Real. Cherem drives us there in his 4x4. We go through the sprawling suburb of Interlomas, with its quasi-American malls, ugly towers and fast food chains, which are punctuated by rocky outcrops and deep ravines.

We pay a toll to enter Bosque Real. It has an international golf course, a luxury clubhouse designed by Mexican architect Humberto Artigas and roundabouts decorated with giant abstract sculptures by the artist Sebastián. It feels deserted. The only people we see are the uniformed maids who run the house, which sits in on the edge of the golf course, surrounded by trees and a waterfall, which bubbles with pollution foam.

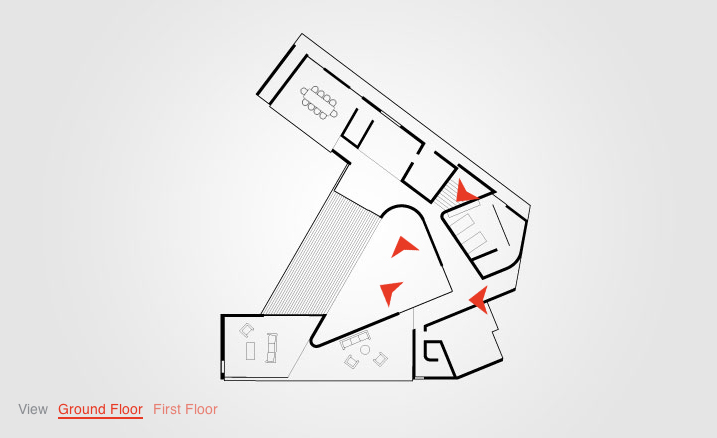

Cherem oriented the house as best he could in order to minimise views of the suburban sprawl that surrounds it on every side, but telltale tower blocks creep into the vistas. The house is a complex marriage of rectangles and curves; its surface is zigzagged in places and smooth in others. Its walls are 44cm thick (to combat those earth yawns).

Cherem was inspired by the way Brazilians Lina Bo Bardi and Oscar Niemeyer used concrete, and he enthusiastically points out every detail; the way the shadows fall at different times of day, how he made the light wells by pouring concrete around traffic cones, how the interior walls, are 'like concrete curtains, which slide to let the light enter the space'.

He created some elegant wooden furniture for the house, which he enjoys but does more as a hobby than anything else. His own apartment in Bosques de Las Lomas, which he shares with his wife, is filled with it, and he's currently designing a showroom in Miami for Gervasoni.

These days, Cherem operates solo. Two years ago, his business partner was shot dead in a drunken incident. Cherem's father is an architect and prominent property developer; his partner was the son of architect Francisco Serrano. 'A big part of our education and growth was because we had my father and Serrano nearby. Working with them enabled us to grow in a different way,' he concedes. The pair designed an apartment in their third semester at Mexico City's Universidad Iberoamericana, before founding Cherem + Serrano in 2008. El Japonez and a series of other cool restaurants followed. Their contacts undoubtedly helped them get started, but today, Cherem's reputation brings in the work.

Next year sees the opening of his Acre hotel in Los Cabos on the northern peninsula. In addition to 180 rooms, 30 tree houses and 150 villas, the hotel will run an organic farm and will produce all its own fruit, vegetables and lavender-based creams, scents and drinks. Taking eco-tourism to advanced levels, guests can get involved in production, and work on the land if they wish.

He is also designing Candelaria House, a 90m long, single storey house for a client in San Miguel de Allende. It is made of black, rammed earth, taken from the site, the effect being to 'make the house appear and disappear at the same time.' Consisting of a series of independent pavilions joined by patios and decks, with a natural swimming pool at its heart, it will be a strikingly modern addition to the Baroque town.

We leave Bosque Real and head back to the city centre to where Cherem-designed restaurants, hairdressers and boutiques buzz with people. En route we talk about the new Jumex Museum by David Chipperfield that opened last October. It sets a new benchmark for contemporary architecture in the city and Cherem, for one, is delighted.

The concrete landmark sits within Mexico City's gated suburb of Bosque Real - the area's landscape punctuated by rocky outcrops and deep ravines

Cherem oriented the house as best he could in order to minimise views of the suburban sprawl that surrounds it on every side

The home sits on the edge of a golf course surrounded by trees and a waterfall

The house is a complex marriage of rectangles and curves; its surface is zigzagged in places and smooth in others

Its walls are 44cm thick to combat the region's earth tremors

Cherem was inspired by the way Brazilians Lina Bo Bardi and Oscar Niemeyer used concrete

He explains how he made the light wells by pouring concrete around traffic cones

The interior walls are 'like concrete curtains, which slide to let the light enter the space,' he says

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Emma O'Kelly is a freelance journalist and author based in London. Her books include Sauna: The Power of Deep Heat and she is currently working on a UK guide to wild saunas, due to be published in 2025.