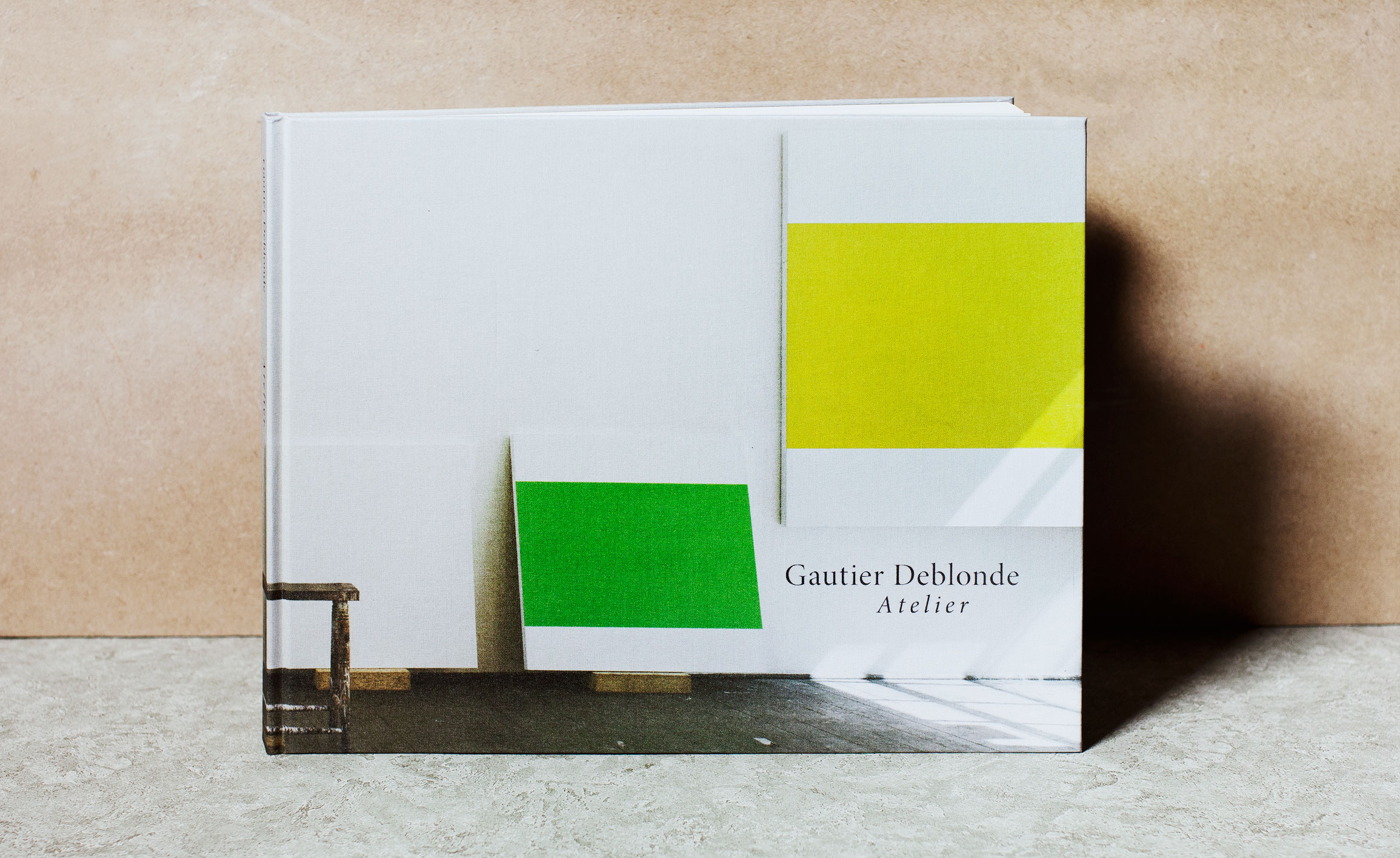

Gautier Deblonde captures artists’ inner sanctums in new book ’Atelier’

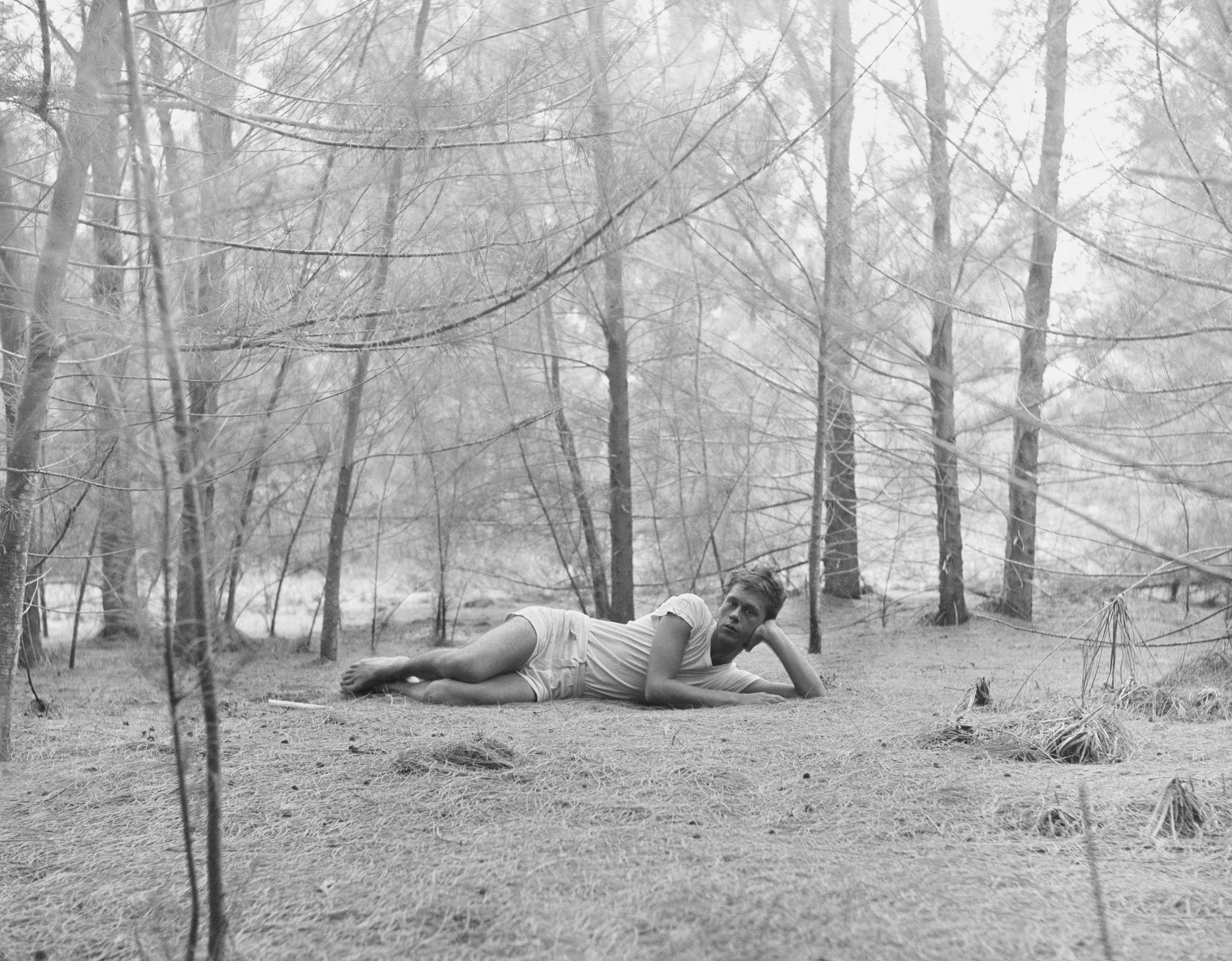

For ten years the French but London-based photographer Gautier Deblonde has been taking portraits of the artist in absentia, 130 of them at the last count. The central conceit of this series is that the artist's studio, unmanned but in motion, populated with works in progress, is an effective - and instructive - stand in for the artist themselves (even if the identity of the artist is not always immediately obvious or they have reversed all their canvases, as Howard Hodgkin seems to have done).

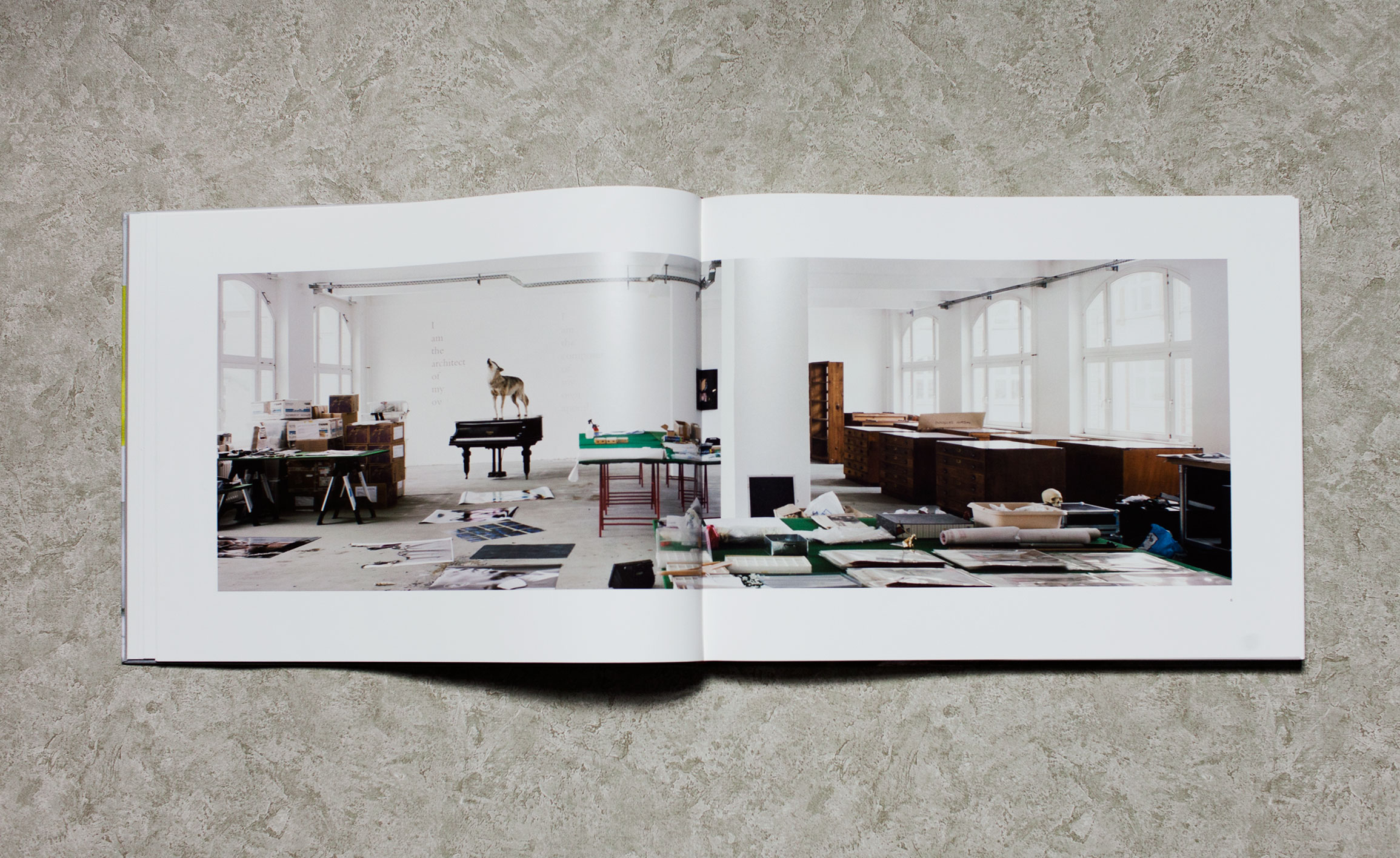

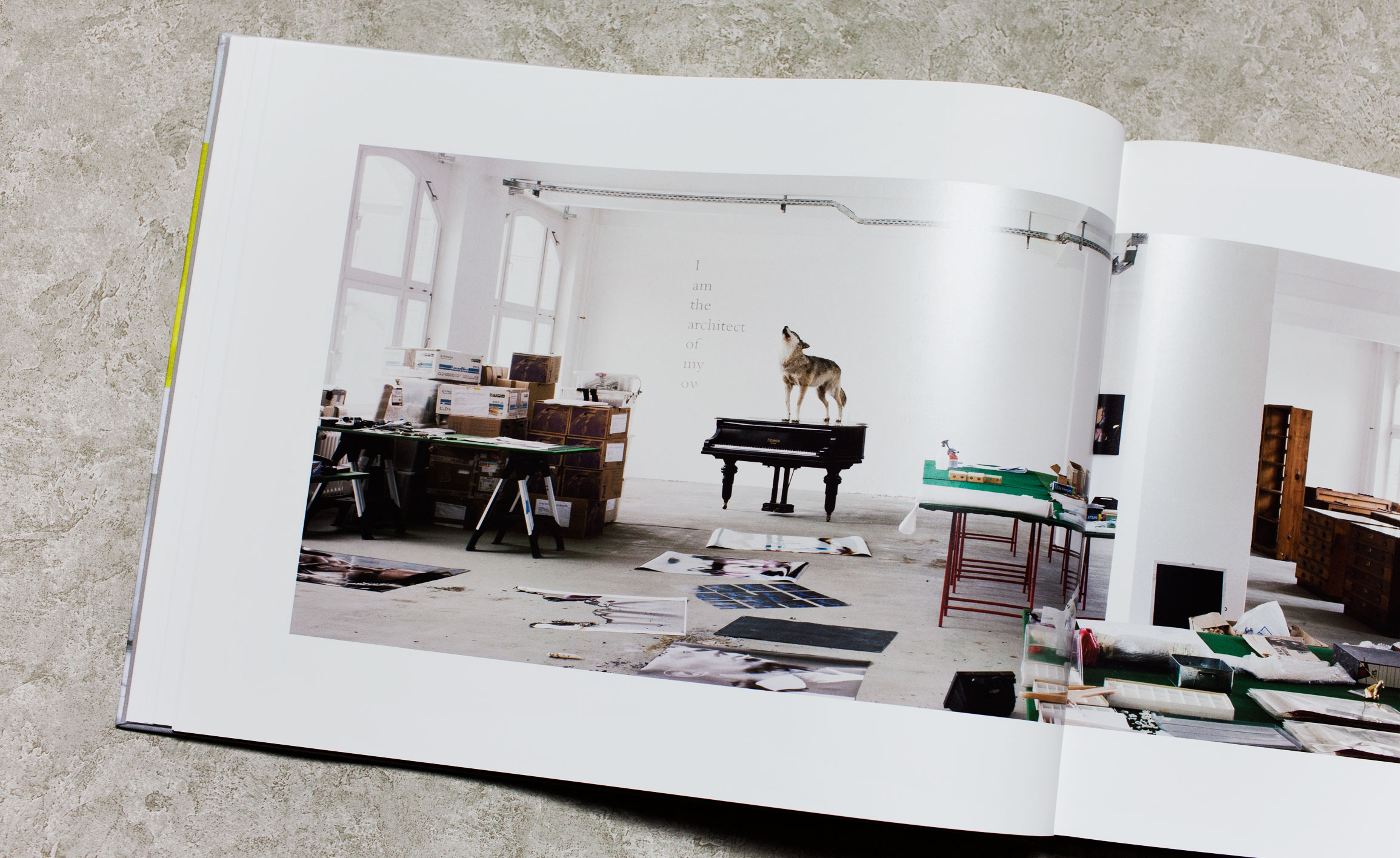

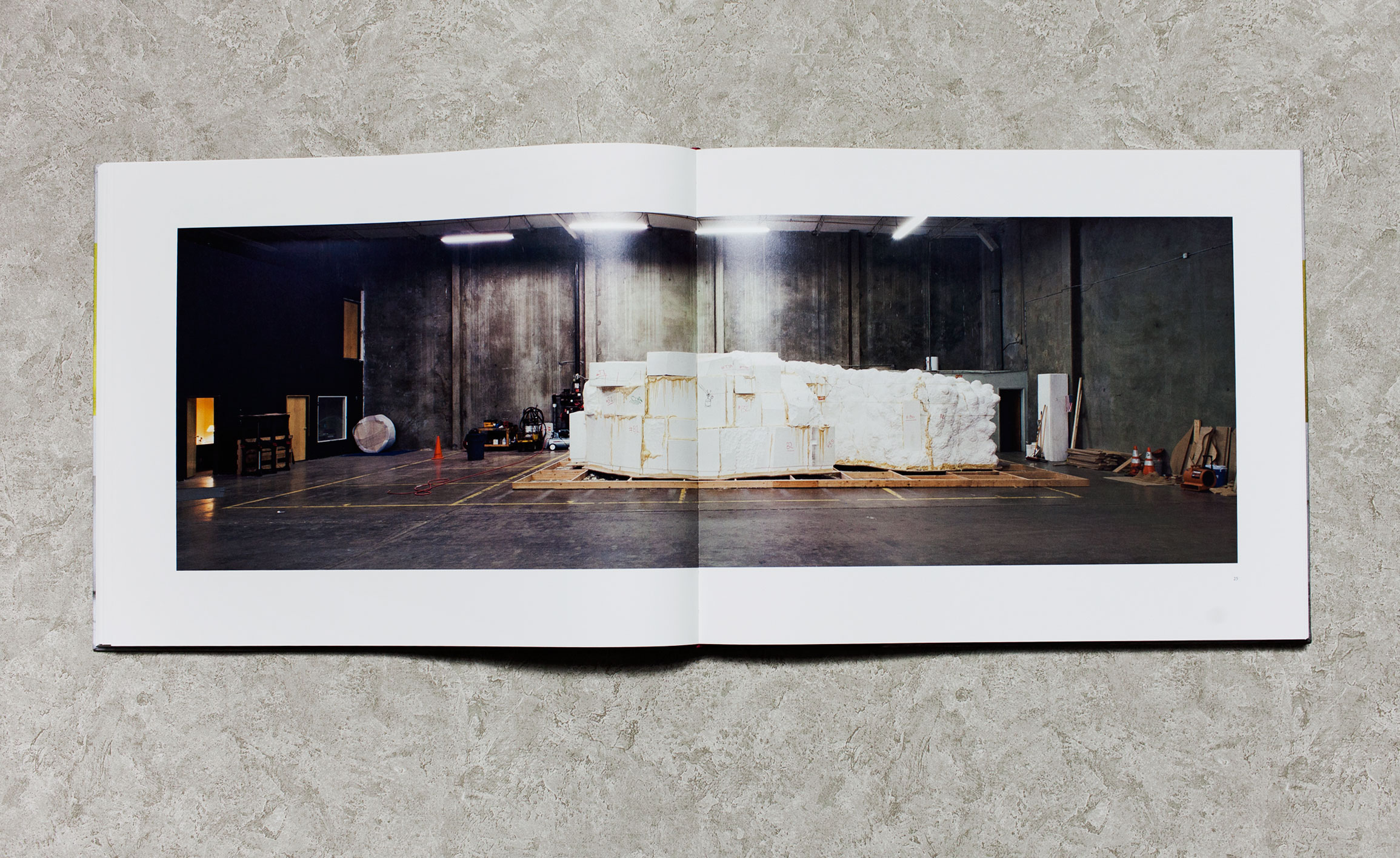

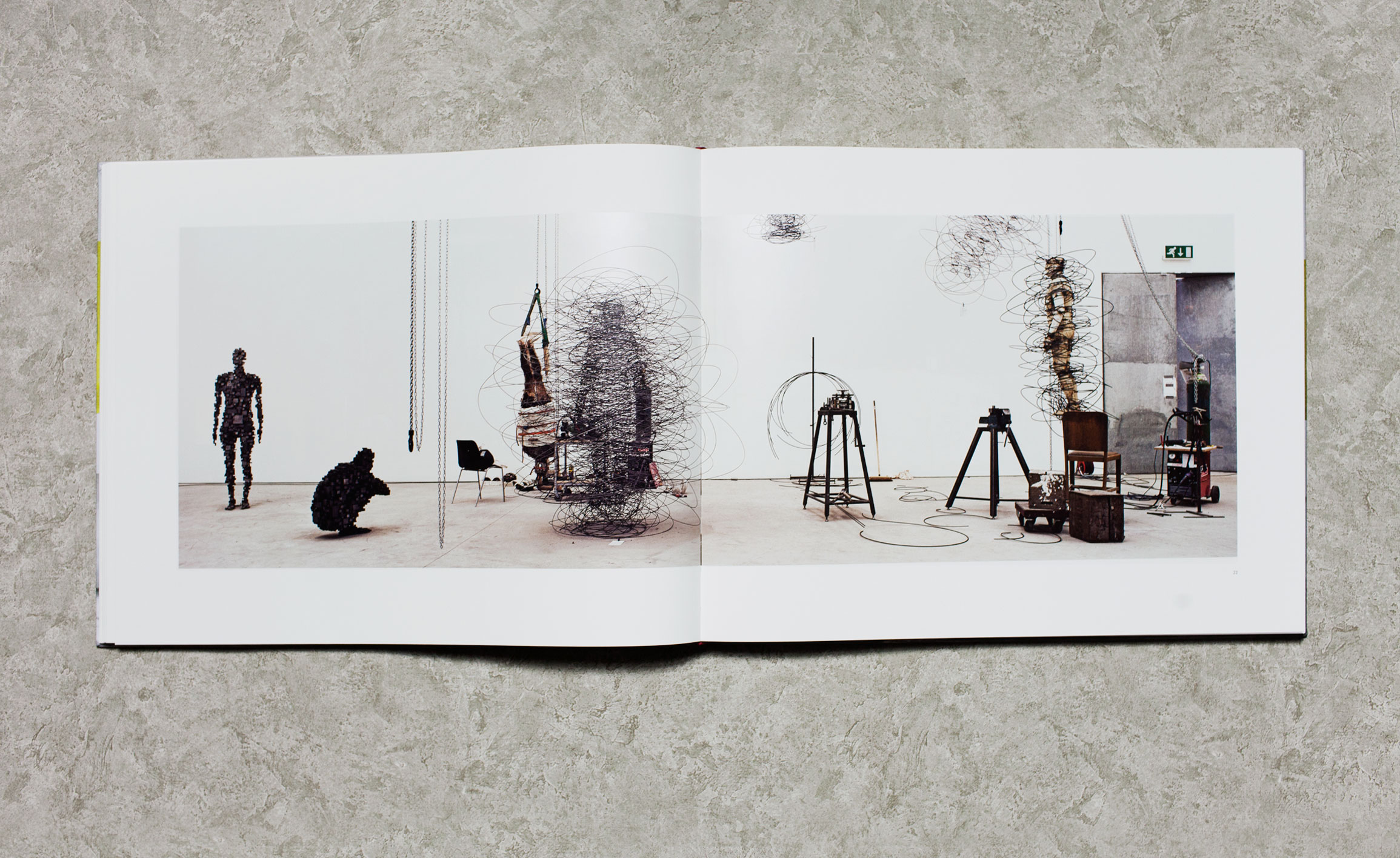

A 69-strong selection of these images has now been collected in Atelier. Including the studios of Richter to Serra, Hodgkin to Hockney, Koons to Kusama, these are varied landscapes always framed the same way. Or, as the art writer Jim Lewis suggests in the great intro to the book, freight train carriages scudding across a landscape, identical in size and fundamental architecture but carrying different cargo - Gormley's pixilated or re- or de-materialising figures, beamed up Star Trek-style, or Douglas Gordon's howling hound.

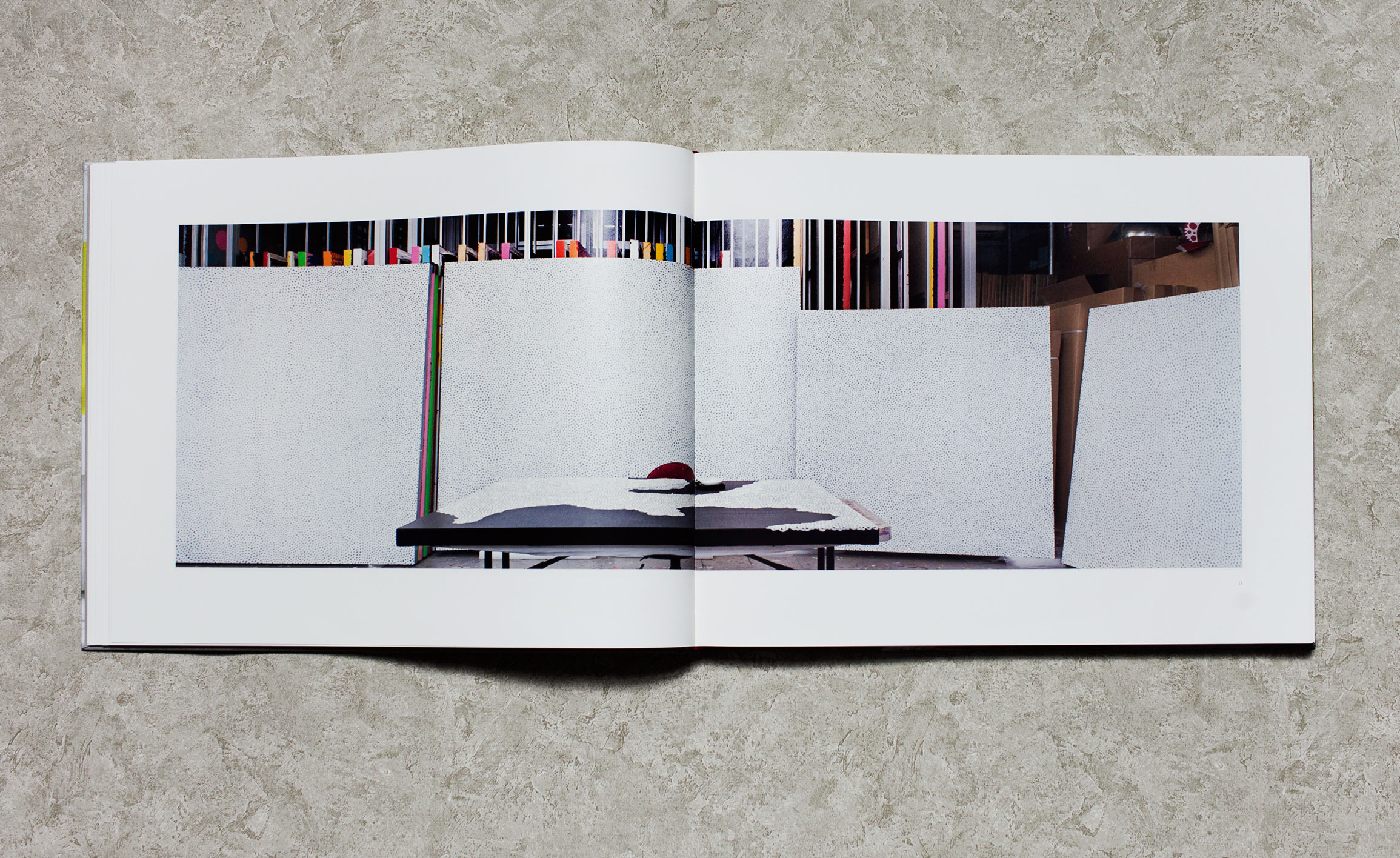

What is remarkable though is how much the artists have resisted the 'white cube' homogeneity of the gallery space when it comes to their creative environments (as Elmgreen & Dragset pointed out, not even McDonalds are the same everywhere). Some of course are the emptiest of spaces and industrial in scale. Others though are domestic and homely, while some are grand.

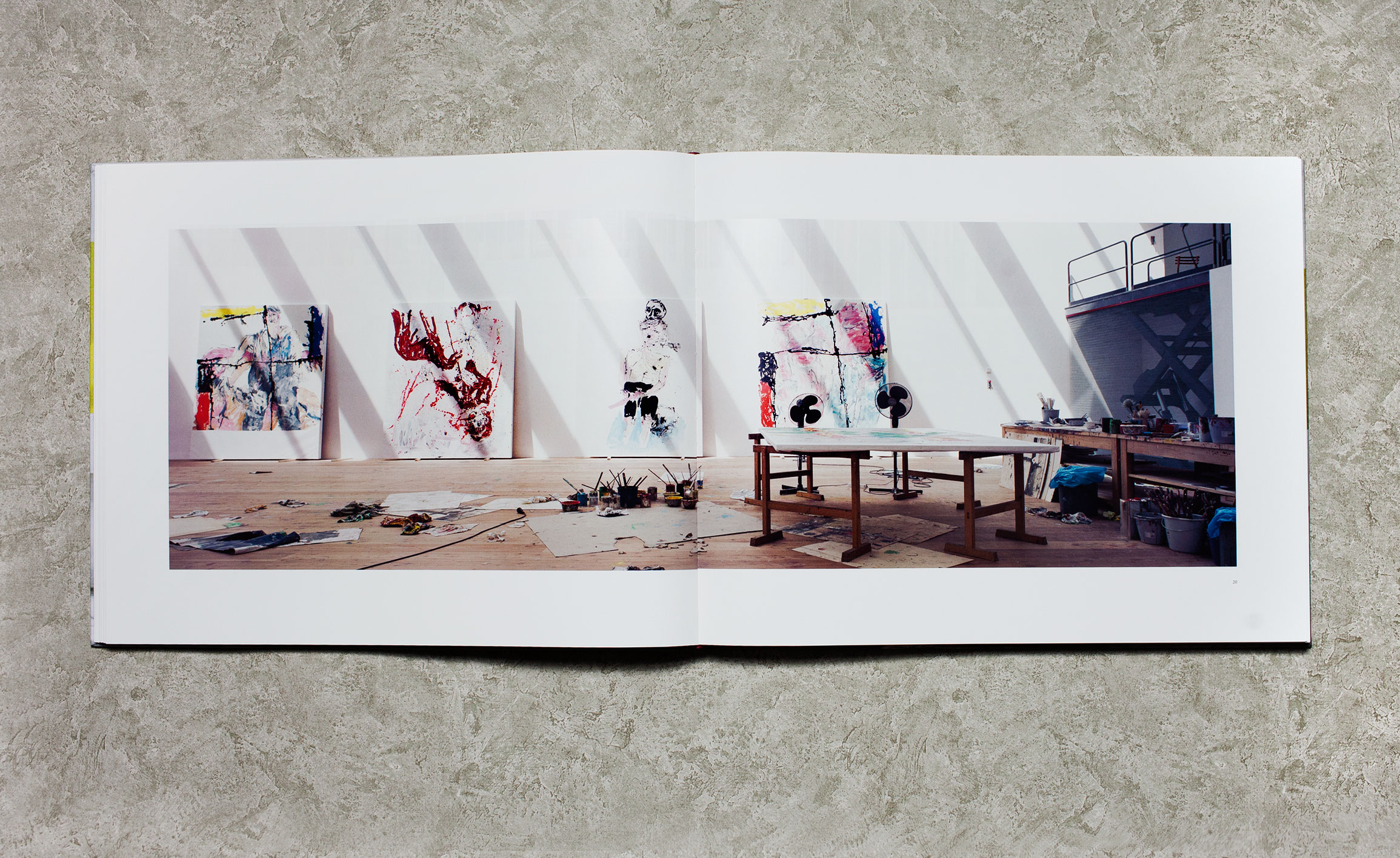

The real joy of the series though - in an age when most creative work seems to involve pecking at a laptop - is that the work, the process and the raw materials are so visible, tangible and there.

We spoke with Gautier Deblonde about artists, access and the art of persuasion...

W*: How difficult was it to persuade the artists to be part of the project? Did you develop one persuasive argument that seemed to work or did you have to try different tactics in every case? Or were people remarkably willing to be involved?

GD: I have worked with artists for almost 20 years and I knew some of them personally, which made it easier to start the project. It still took 10 years to complete; the first studio was shot in 2004. I managed, for most artists, to get their personal address and I wrote to them all. I explained that I wanted to capture what the studio reveals about the artists and their works but through an image of the space with the artist absent. I told them that it could still be seen as a portrait of the artist. And the artists realised that I knew their work well, which was very important. I just had to be patient. Most responded fairly quickly, positively or not. The difficulty was to get into the studio at the right time. I wanted to see some of the work in progress and sometimes I waited one year to get the image.

W*: How long did you have to spend at each studio to get the shot that you wanted?

GD: Most studios were shot at lunchtime. I usually spent the morning looking at the studio, looking at people working and thinking about my image. To shoot the studio during lunchtime was very important. The work has stopped but is about to start again in an hour or two; it is not the end of the day. People don't clean the space before lunch, everything is left as it was, ready to start again. That created the tension I was looking for.

W*: How did you make sure that the artists hadn't 'composed' the studio themselves before you arrived?

GD: I couldn't be sure of that. I asked them not to re-organize the studio for me but they were free to do it, if they wanted to. I never re-organise the studio myself.

W*: Do you think that the artists view their studios as purely functional spaces? Just the right amount of light and square feet? Or do you think the connection to the space can go deeper than that?

GD: The artists move to a studio with their work in mind - the space has to respond to their ambition. The artist chooses the studio, but the studio can have a real influence on the work, because of the size, the light or the location.

The studio is the space of one artist and one only. Some artists can have many assistants or technicians, but the identity of the studio is the identity of the artist, always.

W*: Why that insistence that the artist isn't in the picture?

GD: I always thought of Atelier as a series of portrait of artists. But it isn't always easy to shoot portraits of artists in their studio. They have big personalities and photographing them in their own spaces doesn't necessarily help. They are very well aware of their image and can control it. The studios do reflect a lot of their personality. Photographing their spaces, by myself, makes the relationship equal; it is the studio and me. In some ways, the absence of the artists makes them even more present. It was also a bit easier to organise the project. Most artists in the book are well established and have very busy schedules. Asking them to do their portrait without asking for their time was a great idea to them.

W*: Were any of the artists surprised by your images? In the sense that you saw things that they didn't? Or captured something that they hadn't realised was there?

GD: The artists left me free to roam, but felt they were able to keep some control over the representation of their studio. They were surprised by my presence in their space, something they didn't expect. The panorama gives an overview of the studio but allows you to look at every detail, to wander into the space. The studio becomes a landscape. That was something that surprised some of the artists too.

W*: Do you think of it as an on-going project? Are there still emerging artists whose studios you would like to get inside?

GD: I will always work with artists but I don't have the ambition to make Atelier 2. It would be a mistake.

W*: And is there still one studio you don't have in the collection that you would like to have in there?

I have photographed over 130 studios and we kept the best images for the book, 69 in total. I am very pleased with Atelier. We did the best we could.

Georg Baselitz, Munich, 2008

Yayoi Kusama, Tokyo, 2013

Douglas Gordon, Berlin, 2011

Detail of Douglas Gordon's studio

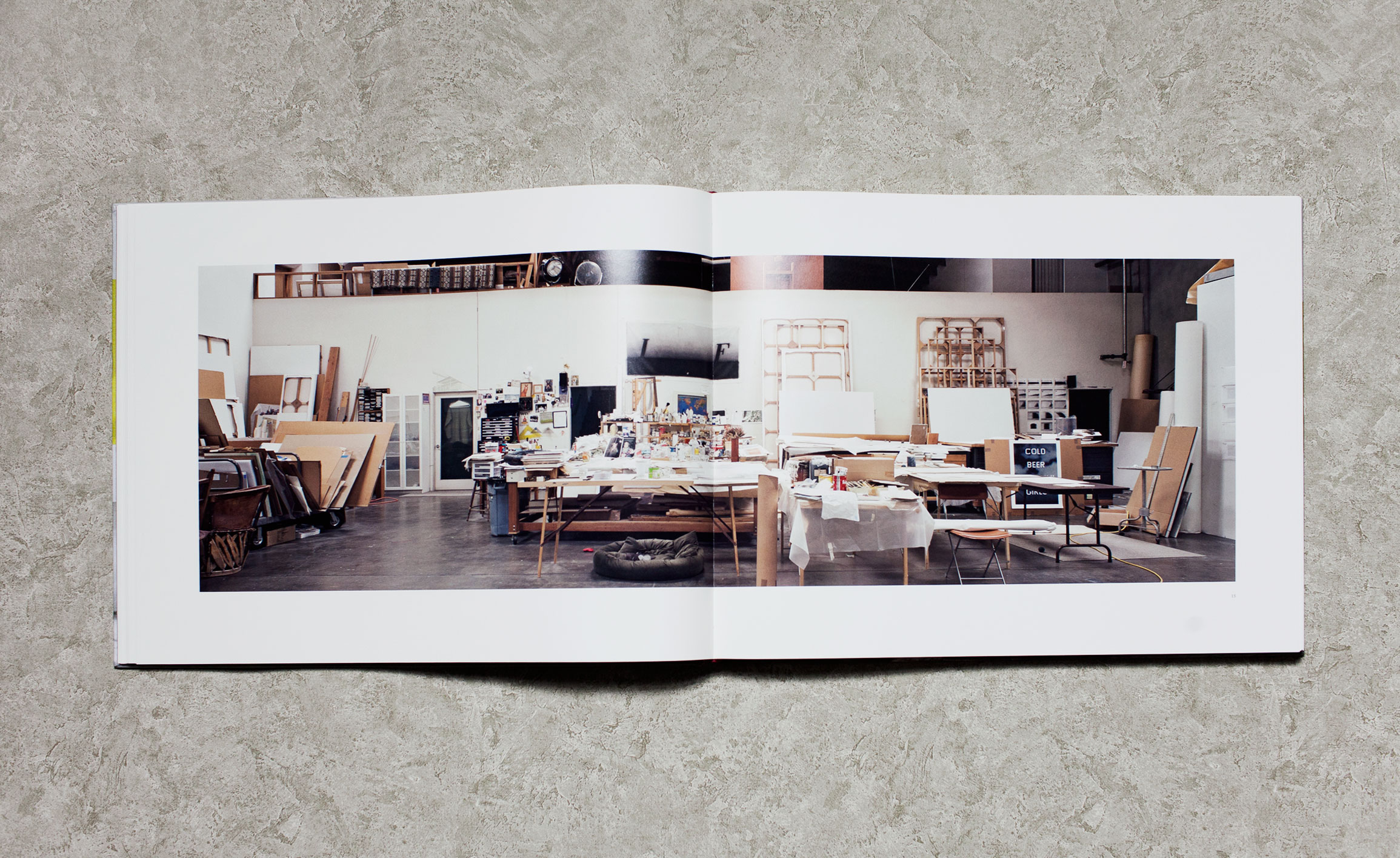

Ed Ruscha, Los Angeles, 2009

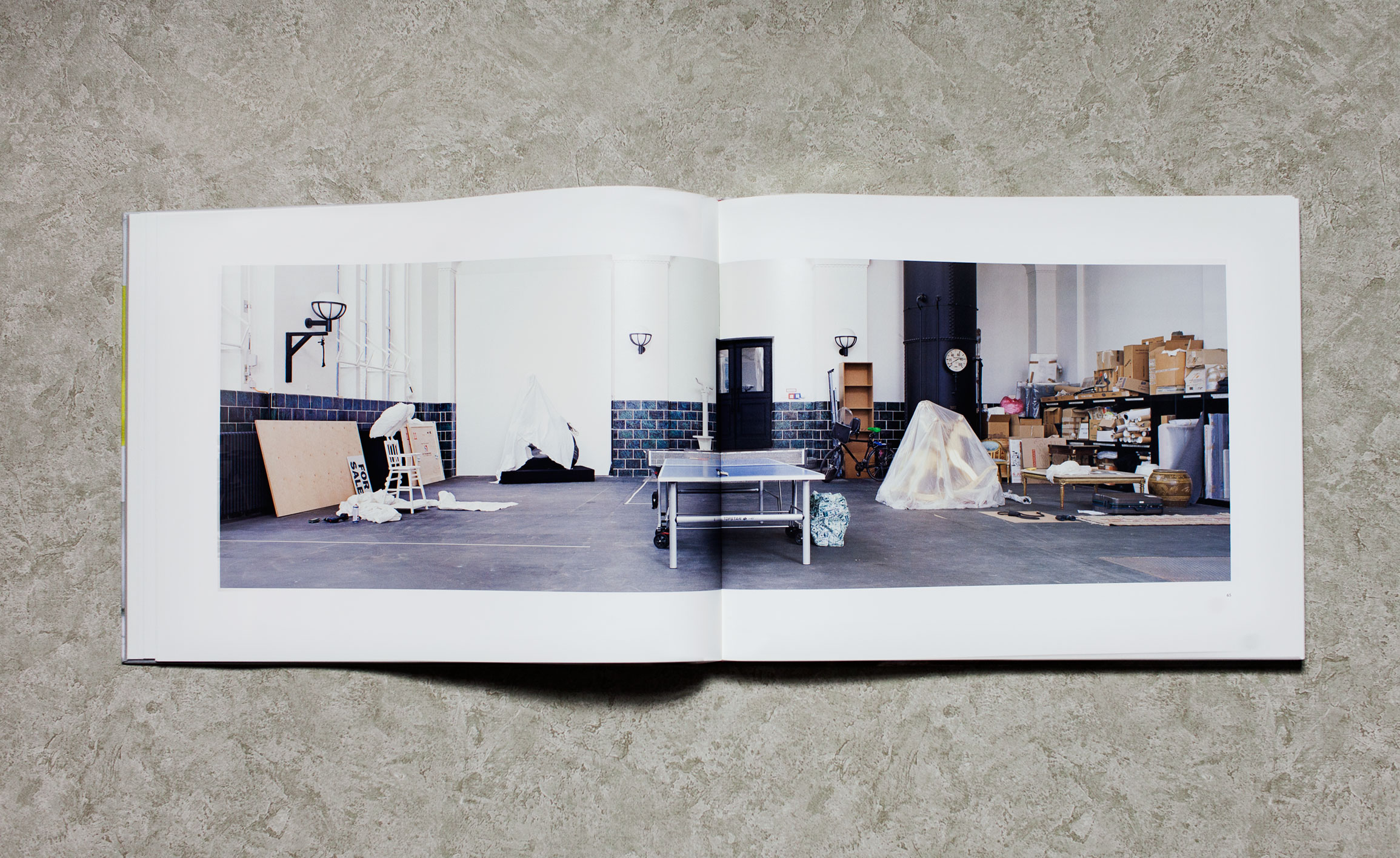

Elmgreen & Dragset, Berlin, 2013

Mike Kelley, Los Angeles, 2009

Antony Gormley, London, 2014

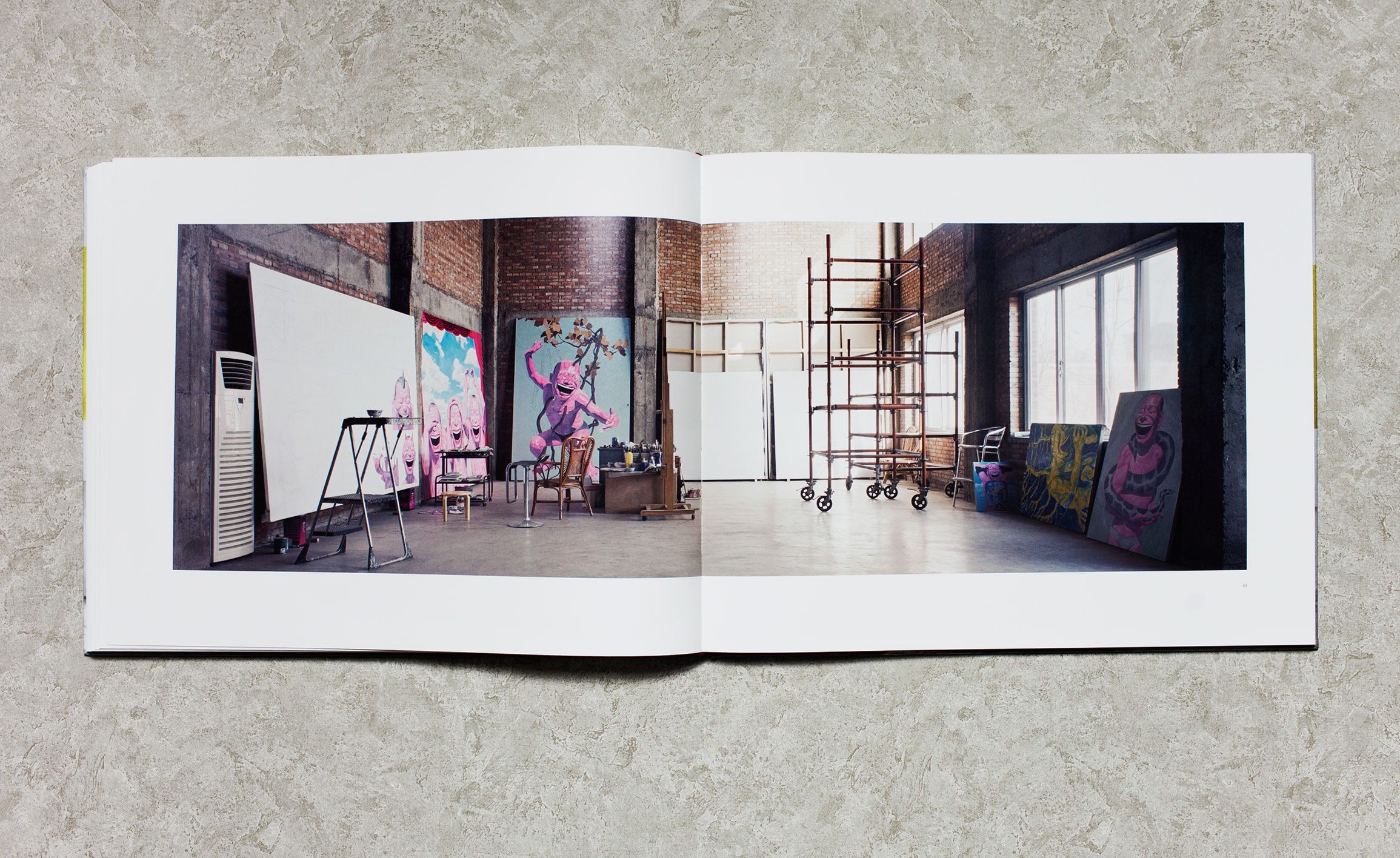

For our Made in China issue (W*123) in 2009, we sent Deblonde to Beijing to shoot the mega-ateliers of China's art aristocracy. Pictured is the studio of Yue Minjun

Franz West, Vienna, 2008

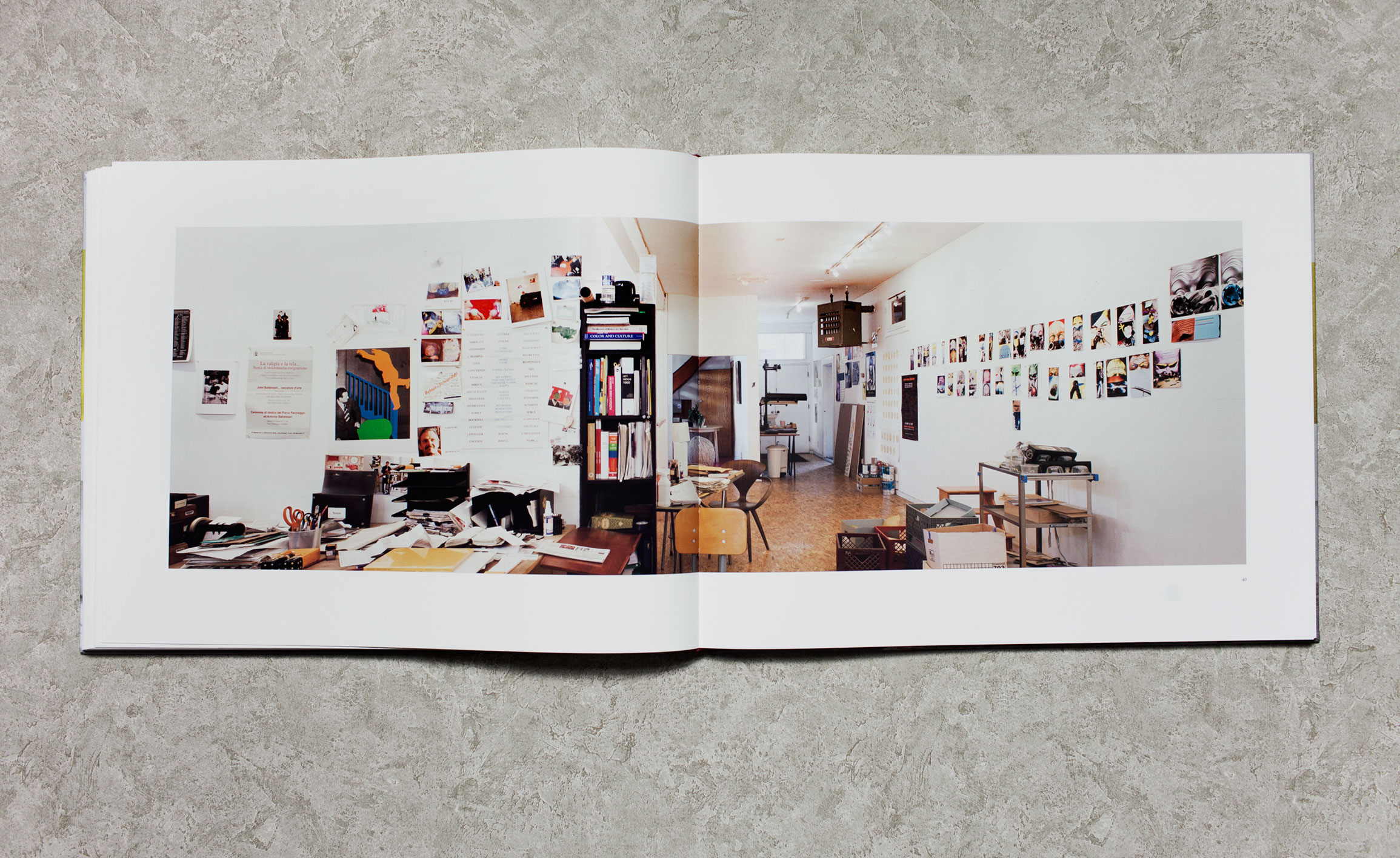

John Baldessari, Los Angeles, 2009

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Inside a creative couple's magical, circular Indian home, 'like a fruit'

Inside a creative couple's magical, circular Indian home, 'like a fruit'We paid a visit to architect Sandeep Virmani and social activist Sushma Iyengar at their circular home in Bhuj, India; architect, writer and photographer Nipun Prabhakar tells the story

-

Ten of the best track jackets for channelling a 1970s-meets-1990s cool

Ten of the best track jackets for channelling a 1970s-meets-1990s coolAs a ‘Marty Supreme’ track jacket makes a bid for viral garment of 2025 – thanks to one Timothée Chalamet – the Wallpaper* style team selects ten of the best tracksuit and coach jackets for men and women, each encapsulating an easy, nostalgia-tinged elegance

-

Eight questions for Bianca Censori, as she unveils her debut performance

Eight questions for Bianca Censori, as she unveils her debut performanceBianca Censori has presented her first exhibition and performance, BIO POP, in Seoul, South Korea

-

Inside the seductive and mischievous relationship between Paul Thek and Peter Hujar

Inside the seductive and mischievous relationship between Paul Thek and Peter HujarUntil now, little has been known about the deep friendship between artist Thek and photographer Hujar, something set to change with the release of their previously unpublished letters and photographs

-

Nadia Lee Cohen distils a distant American memory into an unflinching new photo book

Nadia Lee Cohen distils a distant American memory into an unflinching new photo book‘Holy Ohio’ documents the British photographer and filmmaker’s personal journey as she reconnects with distant family and her earliest American memories

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThe rain is falling, the nights are closing in, and it’s still a bit too early to get excited for Christmas, but this week, the Wallpaper* team brought warmth to the gloom with cosy interiors, good books, and a Hebridean dram

-

Inside Davé, Polaroids from a little-known Paris hotspot where the A-list played

Inside Davé, Polaroids from a little-known Paris hotspot where the A-list playedChinese restaurant Davé drew in A-list celebrities for three decades. What happened behind closed doors? A new book of Polaroids looks back

-

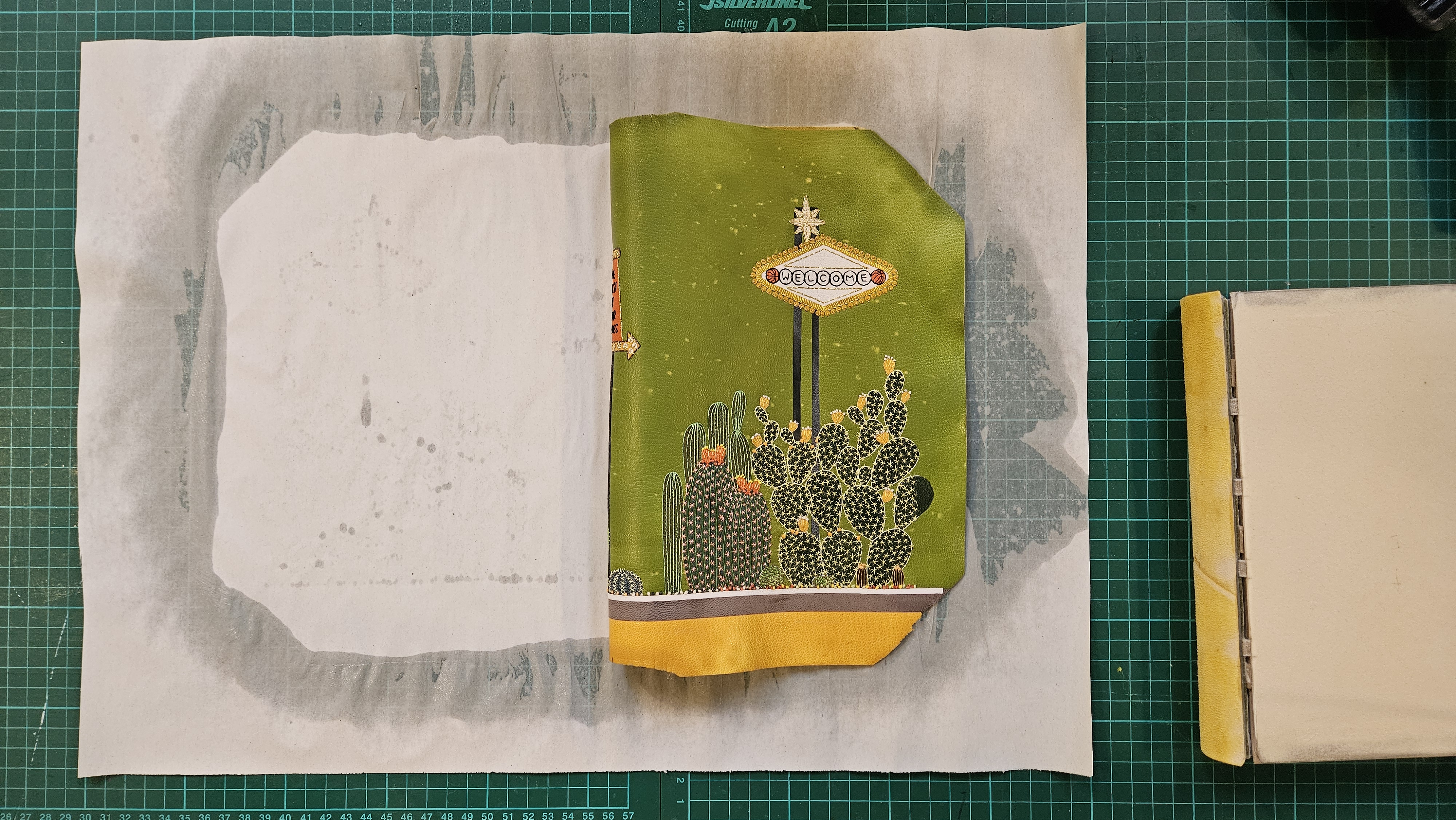

Inside the process of creating the one-of-a-kind book edition gifted to the Booker Prize shortlisted authors

Inside the process of creating the one-of-a-kind book edition gifted to the Booker Prize shortlisted authorsFor over 30 years each work on the Booker Prize shortlist are assigned an artisan bookbinder to produce a one-off edition for the author. We meet one of the artists behind this year’s creations

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThis week, the Wallpaper* editors curated a diverse mix of experiences, from meeting diamond entrepreneurs and exploring perfume exhibitions to indulging in the the spectacle of a Middle Eastern Christmas

-

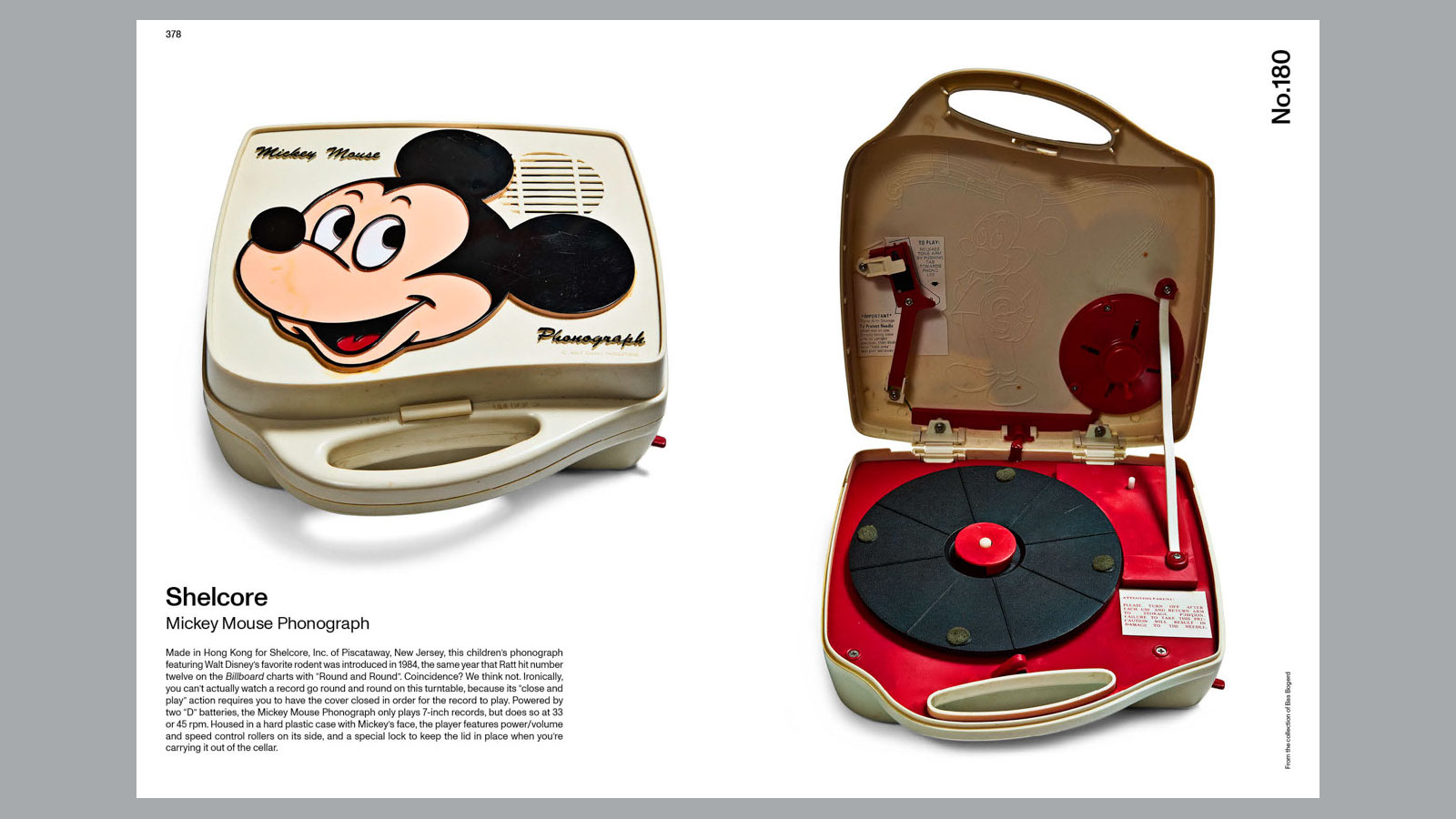

14 of the best new books for music buffs

14 of the best new books for music buffsFrom music-making tech to NME cover stars, portable turntables and the story behind industry legends – new books about the culture and craft of recorded sound

-

Jamel Shabazz’s photographs are a love letter to Prospect Park

Jamel Shabazz’s photographs are a love letter to Prospect ParkIn a new book, ‘Prospect Park: Photographs of a Brooklyn Oasis, 1980 to 2025’, Jamel Shabazz discovers a warmer side of human nature