Grima the great: a personal recollection of a 1960s jewellery design visionary

On the eve of the Bonhams London sale of the largest private collection of Andrew Grima jewellery ever to come to auction, we speak to the legendary London jeweller’s daughter. His design heir, Francesca Grima continues her father's eponymous jewellery brand today. Here, Francesca gives Wallpaper* a personal insight into her father’s unique design vision...

W*: Your father, Andrew Grima, did not train as a jeweller – he was someone who, first and foremost, seemed to love to draw…

Francesca Grima: My father was born into a very artistic family (architects, fashion designers, painters) and I believe that creativity ran in his blood. This first manifested itself when he spent weekends as a teenager cycling through the English countryside drawing picturesque villages, houses and farming equipment.

How did Grima’s engineering background influence his vision for jewellery design?

That training meant that he was always looking for innovative techniques to translate into jewellery. But my father didn't have any training or education in jewellery design. He could have chosen any medium to express his creativity. Jewellery crossed my father's path when he joined his father-in-law's jewellery business in the 1950s but he never felt constrained to keeping within the ‘rules’ of jewellery design.

Grima jewellery is often distinguished, at first glance, by its abstract gold work. There’s a strong message in that.

He always chose textured gold over polished gold. Many of his designs have a large semi-precious stone as the protagonist and textured gold surrounding it. At times, the effect is of the stone growing naturally from a base of gold, textured to mimic the natural inclusions and texture of the stone.

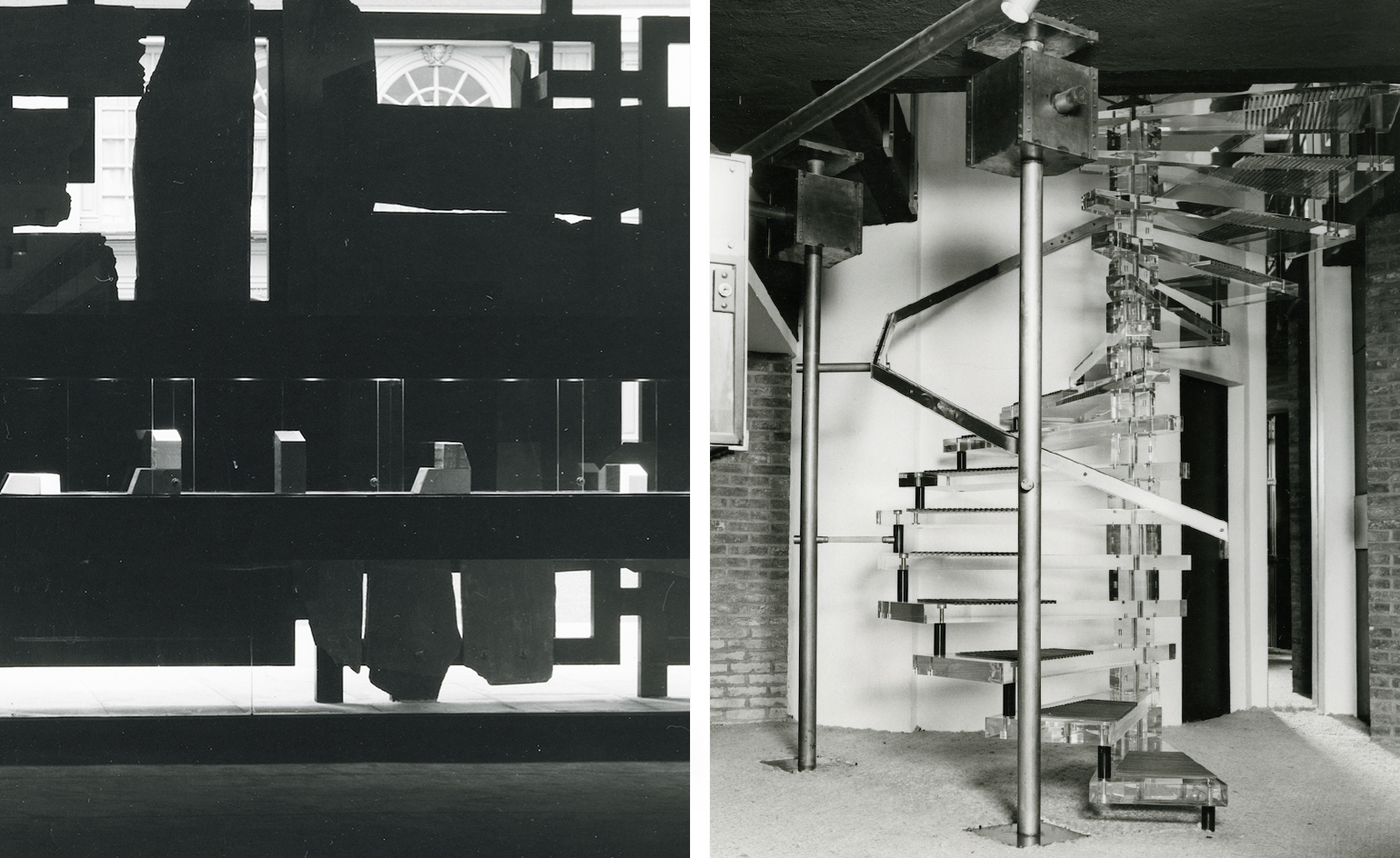

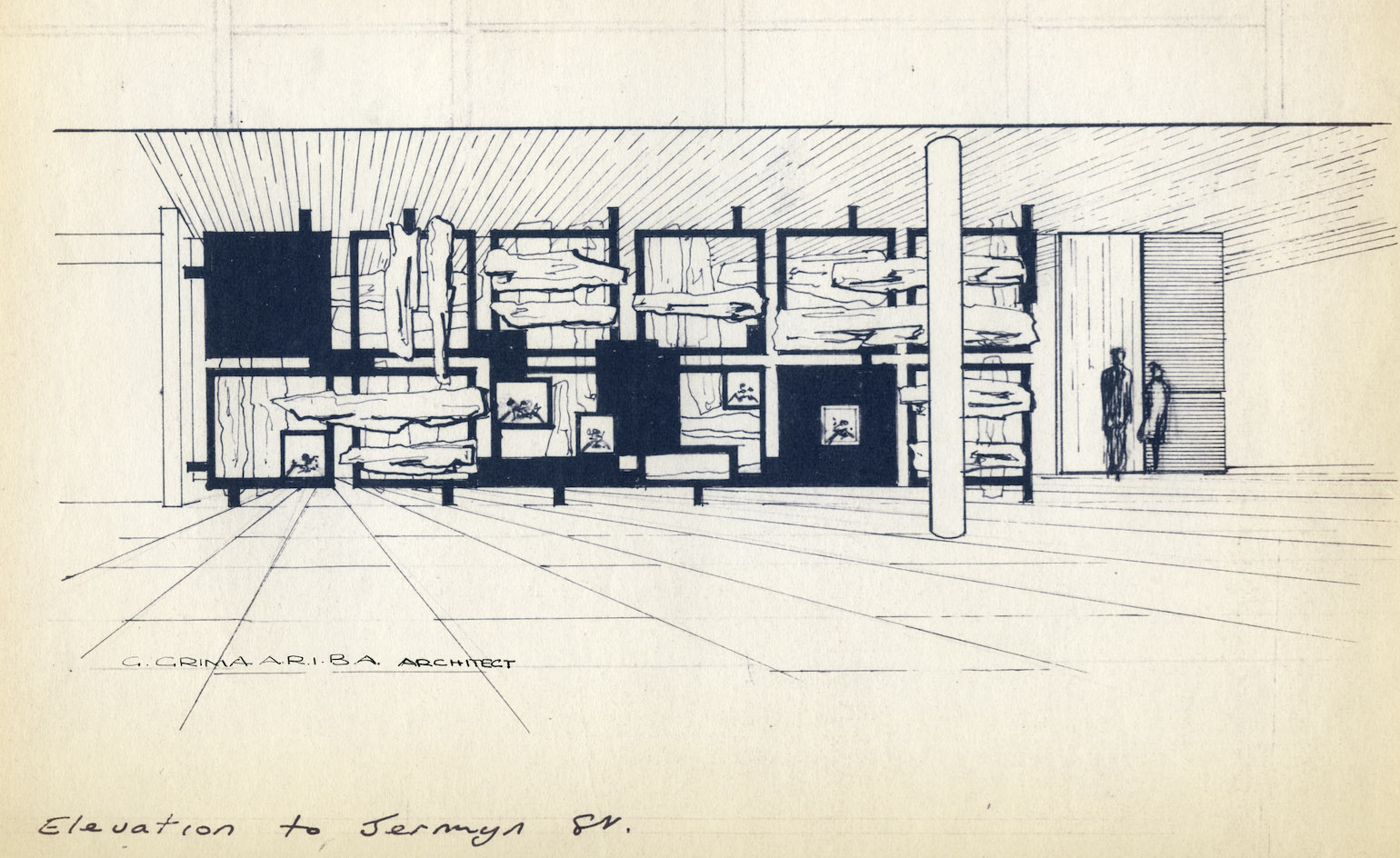

The Grima 1960s boutique in Jermyn Street, London, was designed around a central staircase by Ove Arup. How did the boutique design evolve?

The London boutique was designed by my father’s architect brothers Godfrey and George Grima. The façade was a large screen designed by sculptor Bryan Kneale RA, formed of slabs of slate bolted on a steel framework. A massive cast aluminum door by Geoffrey Clark protected the entrance to the boutique and was opened automatically from the inside. The confidence my father had in designing jewellery also translated into a confidence in his shop design. Before opening to the public, he had a soft opening for the trade. I have heard from many people that there were whispers of ‘this is madness and will never work’ between other jewellers that evening. Not only was the shop design something they had never seen before but the location on Jermyn Street was unusual as it was known as the place one would go to buy a shirt or a suit, not jewellery. My father thought that men would visit Jermyn Street to buy their clothes, spot the shop and be intrigued and tempted to buy something for their wives. My father was quick to prove everyone wrong.

The jewels have a particular – and fine – organic realism. What techniques did Grima employ to achieve that?

My father drew on his engineering background to experiment with techniques that had never been used in jewellery making. He would cast leaves, lichen and even pencil shavings using the lost wax process to achieve a very organic and naturalistic design.

Grima’s ‘About Time’ watch designs for Omega in the late 1960s have proved hugely collectable among renowned designers today. How did the association come about?

When Omega approached my father with the idea of him designing a collection for them, his first condition was that he should be given creative carte blanche. He didn’t want to design watches that looked like watches; he wanted to design a collection of striking jewellery that happened to tell the time. His craftsmen were given dummy movements which they would make the watches around in the London workshop and when they were finished, a few goldsmiths would travel from London to the Omega headquarters and fit the movements with the aid of the Swiss watchmakers.

There’re a sense of otherworldliness about Grima jewellery design. Tell us more about that.

When he was designing in the 1950s I think my father was revolting against the delicate designs of the day; most women wore bees and bows and he decided it was time to add boldness and volume to jewellery. His pieces mirrored the positivity of the 1960s in other areas too, such as the rising popularity of air travel, automobiles, (colour) television and a general hunger for innovation and the new. Great designers often challenge the status quo. My father was not burdened with the preconceptions of what jewellery should look like and ultimately, my father wanted to create pieces that were timeless and unique. That is what he cared about.

The facade of the Andrew Grima Zurich store

Left, Grima’s ’pencil shavings’ series was a typically witty, fresh and exquisite take on jewellery design. Right, Andrew Grima photographed in the Jermyn Street boutique

Left, Andrew Grima’s sketches for the ’About Time’ series of watches, made in collaboration with Omega. Right, ’About Time’ gold watch with tourmaline-covered dial

Grima’s Jermyn Street boutique was designed around a frieze using giant slabs of slate by the sculptor Bryan Kneale. The internal central staircase, right, was designed by Ove Arup

Architect’s drawing of the facade of Grima’s Jermyn Street shop, London. It was designed around a frieze using giant slabs of slate by the sculptor Bryan Kneale

INFORMATION

The private collection of Jewels by Andrew Grima is offered as part of Bonhams London Fine Jewellery sale on 20 September. For more information, visit the Bonhams website and the Grima Jewellery website

ADDRESS

Bonhams

101 New Bond Street

London W1S 1SR

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Caragh McKay is a contributing editor at Wallpaper* and was watches & jewellery director at the magazine between 2011 and 2019. Caragh’s current remit is cross-cultural and her recent stories include the curious tale of how Muhammad Ali met his poetic match in Robert Burns and how a Martin Scorsese Martin film revived a forgotten Osage art.