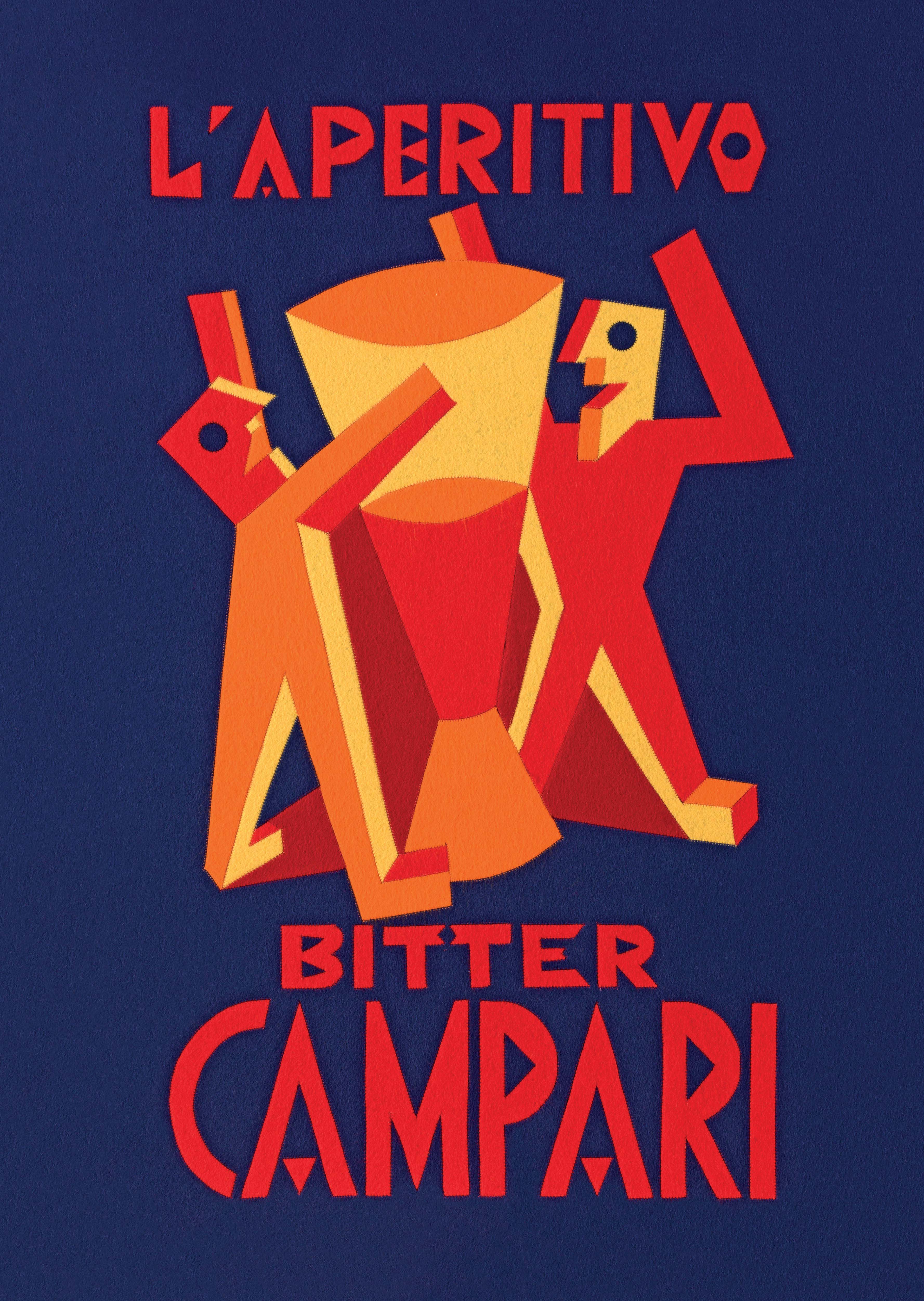

Cin cin: discover the story behind Campari, Milan’s signature aperitivo

Where better to indulge in the delights of the Italian golden hour than Milan, the home of Campari? We trace the origins of the city’s signature aperitivo

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

There's a liquid flowing through Milan as vital as the water running in the river Po; as connected to the city as the river's hidden tapestry of da Vinci-designed navigli – canals – that spread out among the Neoclassical and Gothic constructs and under the feet of the Milanese; as defining of Milan's identity, inwards and outwards, as La Scala opera house or the city’s magnificent cathedral.

The liquid is, of course, Campari.

The history of the aperitivo

If the comparisons sound a little overwrought, an aperitivo pilgrimage to Italy's second (and in many ways, first) city would change the mind of the most ardent cynic. For the uninitiated (surely not?), an aperitivo is a pre-meal drink, designed to get the juices flowing, metaphorically and literally, for the feast ahead. However, the culture of aperitivo dwarfs any idea of a quick snifter before a sandwich: generally observed between 7pm and 9pm across Italy, aperitivo is a national sport, the country coming together to enjoy some light dishes and a drink or two before heading for dinner proper. This is happy hour for grown-ups.

What has made this golden evening activity particularly happy has been the role of Campari as apéritif-in-chief. In 1860, 11 years before the unification of modern-day Italy, Gaspare Campari settled upon a recipe for the bitters-style apéritif he’d been tweaking since the 1840s. Containing an infusion of aromatic herbs, roots, woods, spices, flowers and fruits from across the world – thanks to Italy’s role in global trade at the time – the eponymous drink has barely changed for 162 years, forming a cornerstone of aperitivo that persists to this day.

First stop in Milan for any self-respecting scholar of aperitivo is the magnificent Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, the city’s hyper-fashionable double arcade designed in 1861. Settling in Milan in 1862, Gaspare opened a café neighbouring the cathedral and and nascent Galleria, founding a second café, the Camparino, within the finished arcade five years later. The luxurious, three-storey, brass-and-mosaic bar was where Gaspare perfected Campari, where his son Davide was born, and where the story of the famous red liquid really began to blossom.

The birth of Campari

The business has developed slightly since 1860: Campari Group now owns more than 50 brands, has assets stretching into the billions and recently celebrated its 20th year on the Italian stock exchange. It produces all manner of drinks – big-name whiskies, rums, even the world's first pre-mixed drink, the Campari Soda invented by Davide – but its original tipple still reigns supreme over both the portfolio and the drinks world.

Bruno Malavasi, biochemist and Global Formula & Process director at Campari Group, is a 26-year veteran of the company, having overseen the original recipe for much of that time. The development of the spirit can still be analysed in Gaspare’s original notebooks (understandably under lock and key in the company’s archives), which reflect the country’s leadership in botanical usage: ‘These recipes are all based on the fact that a wide number of botanicals have been available in Italy for centuries,’ Malavasi tells me in Camparino’s plush basement reception. ‘We’ve been used to managing these kinds of materials for ages – the oldest books are from the 15th century, and we have plenty that describe recipes we see now.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘The tradition in southern Europe is to keep these recipes secret. That's why, I guess, the [Campari] recipe is so well-guarded. There's nothing that you can patent at the end of the day. Artemisia is artemisia: you can use it, I can use it, but not in the proportion, or in the cutting that I'm using, or in the way I'm infusing it, or in the way I'm distilling it.‘

The Negroni

The classic Negroni recipe calls for equal parts gin, red vermouth and… Campari. Not a generic spirit, not a flavour that can be replicated and tweaked, like vermouth or (especially) gin, but Campari. It’s that rare sort of product inextricably linked to its name, a more glamorous Hoover, Tannoy and Blu Tack: instantly recognisable, but unlike its more practical peers, impossible to imitate.

Malavasi sees this as Campari’s greatest strength: ‘It’s a wonderful recipe. I know there’s this story that nobody knows how many botanicals there are: somebody says 20, 60, 11, 100, or whatever. It doesn't matter. What really fascinates me is the fact that even if it’s not such a big number, the way the components are so properly blended means that the profile of Campari is just Campari.

‘It has the right strength, right combination of sweetness and bitterness, and most importantly, is incredibly mixable: and even when mixed, it always provides a signature contribution to the profile. Whenever you are mixing it, you can always say, “Yes, there is Campari here.”’

For Milan and aperitivo, it’s a signature that’s not likely to fade. Cin cin.

INFORMATION