Danish brand Lindberg offers divine lightness and infinite variety

A pair of nearly invisible glasses – floating frames formed by two thin, titanium wires stuck straight into small slits in the upper corners of round, rimless lenses – were the signature of my minimalist mother, a Dane living abroad in Washington DC throughout the early 1990s.

The temples were a metallic hue, a less pink version of Apple’s take on rose gold, and I remember the glasses so vividly because, as a small child, removing and replacing the slender silicone tubes that slipped over the ends of the temple pieces to protect the ears became a regular pastime.

Unknowingly, I had been introduced to upmarket Danish eyewear brand Lindberg at a very young age, so when I recently found myself in front of its HQ in Aarhus, Denmark’s second largest city, it was with a hint of nostalgia, and slight embarrassment, as I stood polishing my clunky Warby Parker frames, with the hem of my shirt.

CEO Henrik Lindberg in his private office, Mats Theselius’ ‘Hermit’s Cabin’, on his factory’s open-plan first floor

‘Your eyes, and what’s in front of them, are the first thing people see when they meet you – not your feet, hands or legs,’ says Henrik Lindberg, the company’s founding CEO. ‘So I really don’t grasp when someone puts so much effort into their overall look, and then they just grab their glasses without thought – they don’t polish them, they probably have mushrooms growing on the nose pads – and out the door they go.’

Wearing tapered leather trousers and slip-on trainers, with a mop of frizzy grey hair and Scandinavian-blue eyes framed by black rectangular specs, Henrik recounts a story about a friend who’d recently traded in a lifetime of ill-fitting blue suits for a stylish new wardrobe. But he’d kept the same glasses.

‘I told him: “You’re still wearing the same cheap shit from Hong Kong, which doesn’t suit you – it’s time you think about that”.’ One imagines that Henrik may have subsequently sorted out his mate with a pair of Lindberg frames, as he’s now spent nearly half of his 60 years building a brand that has arguably made the world a slightly prettier place: certainly for those lucky enough to see through Lindberg frames, but also for the rest of us, who knowingly or not, look at others wearing glasses that actually suit them.

Known for lightweight, technically advanced frames that take inspiration from the minimalist aesthetic and impeccable craftsmanship of Danish modernism, Lindberg glasses are a subtle, logo-less calling card for those who treasure function as much as fashion, quality as much as cool-factor. To those in-the-know, Lindberg designs are easy to spot for their clean lines and seamless construction, though it’s admittedly difficult to come across two entirely identical pairs. ‘If you want to calculate all the possible outcomes of how many different styles exist in the Lindberg universe, the number is rather absurd, like six million or something,’ says Henrik.

He breaks down the maths: Lindberg has 13 different collections, each with upwards of 20 different models, and within those designs, there are endless different colourways, finishes and frame sizes to choose from. Then there’s the type, colour and length of the temples, the size of the nose pads, and upward the possibilities climb. The Lindberg system is one of building blocks, where end-consumers can choose to buy a pair of glasses off-the-shelf from their optometrist, or create an entirely bespoke, made-to-order pair from a multitude of pre-determined parts (the custom option isn’t pricier). Lindberg sales consultants tend to lug around 850 different frames when they’re on the road, to offer opticians a small glimpse of what’s on offer.

Production manager Lars Grejsmark quality checking precious frames with team member Ha Hong Nguyen

Henrik himself is in transit for about 180 days of the year, tending to the company’s retail network in 138 countries. But on this particular day he’s in-house, standing in the doorway of an 8 sq m wood cabin. Plopped in the middle of an expansive open-plan workspace on the first floor of the elegantly refurbished, early-20th century factory, home to the brand’s 180 local employees (of 600 globally), this is Henrik’s private office. The one-man abode (aka ‘The Hermit’s Cabin’ by Swedish designer Mats Theselius) is outfitted with a bed, table and chair, and a few shelves. An architect by training, it’s only fitting that Henrik would appreciate the simplicity of the micro-suite, and in a way, the set-up captures some of the values that the brand espouses: minimal and no-fuss, but far from ordinary.

Lindberg burst onto the scene in 1985 with the groundbreaking Air Titanium range (the rimless design my mother wore), which upended the eyewear market with its delicate silhouette that was not only featherweight, but also virtually indestructible. At the time, titanium was not widely available on the consumer market – it was mostly used in the aviation and aerospace industries – but Lindberg had managed to get hold of some titanium wire from an American supplier, and its strength and flexibility meant it could be manipulated to ingenious effect. Lindberg was the first brand to patent an entirely screw-free frame, which remains a signature of its designs today. ‘Screw is a really, really dirty word around here,’ says Henrik.

The Air Titanium model was conceived by Henrik’s optician father, Poul-Jørn Lindberg, and his friend Hans Dissing, an architect who was a key member of Arne Jacobsen’s practice (Dissing and his colleague Otto Weitling took over Jacobsen’s studio after his death, subsequently renaming it Dissing+Weitling). In that sense, the Lindberg brand has always had a very direct link to Danish modernism. ‘Our point of departure is the Danish functionalism and minimalism of the 1950s: it’s a matter of taking materials seriously, of prioritising clear forms, and having an ethos to make things that improve people’s lives,’ says Henrik, who gave up his architecture job to help his father develop the original Lindberg prototype.

Once that launched and found an eager audience, Henrik took the reins of the business and built it from the ground up, while his father remained focused on his optometry practice. Today it is run by Henrik’s sister, and is the brand’s only dedicated retail outpost, as they otherwise sell only through partner optometrists.

‘The design element is very important to me, of course, because without that, the rest doesn’t matter – but design is not just the glasses,’ says Henrik, who works closely with the design team on new models. ‘It’s the way we display our product, the way we market ourselves – it’s everything.’ It could be argued that Lindberg is more of a design firm that happens to specialise in glasses than it is an eyewear brand, and a tour of the Lindberg headquarters reveals something to that effect. A microcosm it truly is, as under one roof all elements of the design, engineering, production, manufacturing and distribution take place; the only thing that appens elsewhere is polishing and assembly, which unfolds in a Lindberg-owned facility in the Philippines.

To one side of Henrik’s cabin, four goldsmiths sit fiddling at microscopes, inserting diamonds into the brand’s successful Precious line of solid gold eyewear, which retails from £1,830 to £180,000. That six-figure pair went to a Chinese client with a penchant for pink diamonds.

We pass a workshop where any tools required by Lindberg’s partner optometrists are designed and manufactured; a graphics department; an in-house photo-studio; and a multilingual customer service centre. The seven-strong design team looks after everything from eyewear to packaging, in-store displays, trade-show booths and the like. An in-house carpentry team executes the majority of the displays and furnishings that the designers dream up. ‘We are maybe a bit nuts, to keep it all in house,’ says Henrik. ‘But we’re OK being a bit nuts. That’s our way to survive, and the only way we know.’

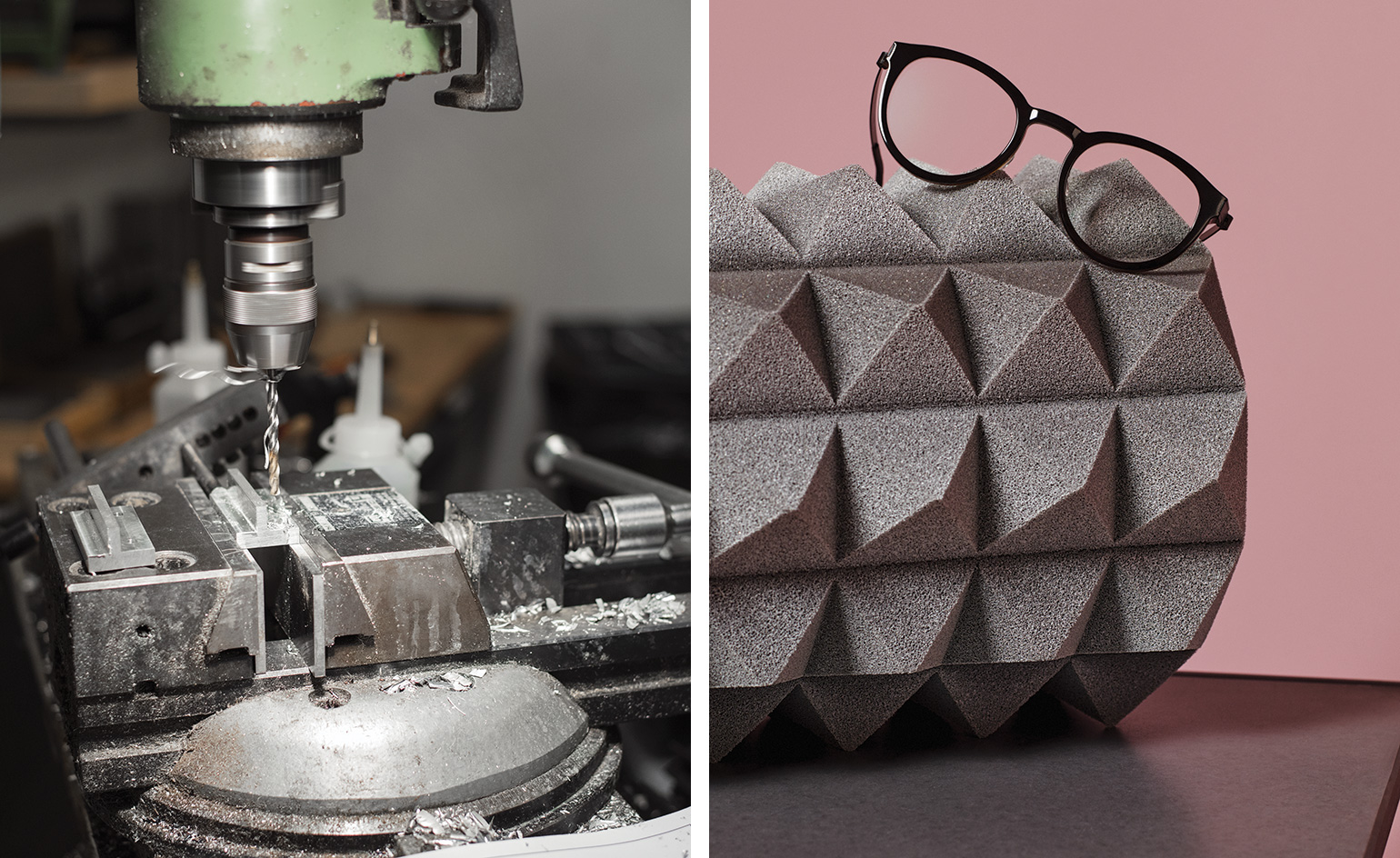

We reach the main production area and here, one of Lindberg’s in-house optometrists, Morten Zacho, leads the way. We inspect state-of-the-art CNC routers stamping out acetate frames, a whirring contraption dedicated to Lindberg’s premium buffalo horn line (a Wallpaper* Design Awards winner for Best Technique in 2015), and two caged machines that look like electronic monkeys bending titanium wires into the right shape and size. Towards the back of the space, Zacho opens the door to a sealed-off room where he proudly points to a big, kiln-like contraption. Here, the company’s recently appointed Chief of Coating apparently researches colour. I ask what that entails, but not much detail is divulged, my only takeaway being that it’s not altogether easy to transform titanium into certain shades.

A Lindberg goldsmith sets a princess-cut diamond on a gold frame

Indeed, because Lindberg manufactures in-house (a rarity in the eyewear business), there are concerns about trade intelligence getting out and there’s a slight air of secrecy surrounding the ins-and-outs of the production process.

By contrast, there is an air of bemused haphazardness about how the company came to find success. With no business acumen whatsoever, Henrik says he has forged Lindberg on instinct and intuition, bringing in a few childhood friends to work with him along the way. It’s worked out well, with Lindberg reporting a turnover of DKK510m (about £46m) in 2015.

In a quiet showroom space near the entrance of Lindberg HQ, rows and rows of Lindberg glasses (and sunglasses) hang neatly on the wall, forming an impressive display of variety: next-gen librarian, aspiring architect, sexy academic, focused financier, Hollywood starlet… there’s something for everyone.

Henrik mentions that, a few months earlier, the company had provided glasses for a four-month-old baby. An optometrist had called from a hospital in Norway to inquire about whether it could customise some of its lightweight children’s frames to fit such a small baby. It could.

Giorgio Armani and Miuccia Prada are repeat clients, and both reportedly have more than 30 pairs (Lindberg is able to keep count, because both like to have their names engraved on the inside of the temple). Queen Margrethe of Denmark is another loyal customer, and then there’s my mum.

When I speak to her a few days later and recount the Lindberg adventure, she says she’s going to try and look for her old frames as her prescription has held steady. She finds them buried in a box somewhere and begins wearing them again some 25 years later –they needed a bit of a polish, but otherwise they were as good as new.

Back at Lindberg, I’d asked: with such a wide variety of styles, does Lindberg even have a target customer? ‘Human beings,’ says Henrik, and with that, there just wasn’t much more left to say.

As originally featured in the November 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*212)

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Lindberg website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling works

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling worksIn an exhibition at Soft Opening, London, Shannon Cartier Lucy revisits childhood memories

-

What one writer learnt in 2025 through exploring the ‘intimate, familiar’ wardrobes of ten friends

What one writer learnt in 2025 through exploring the ‘intimate, familiar’ wardrobes of ten friendsInspired by artist Sophie Calle, Colleen Kelsey’s ‘Wearing It Out’ sees the writer ask ten friends to tell the stories behind their most precious garments – from a wedding dress ordered on a whim to a pair of Prada Mary Janes

-

Year in review: 2025’s top ten cars chosen by transport editor Jonathan Bell

Year in review: 2025’s top ten cars chosen by transport editor Jonathan BellWhat were our chosen conveyances in 2025? These ten cars impressed, either through their look and feel, style, sophistication or all-round practicality

-

How Arne Jacobsen built a whole design universe

How Arne Jacobsen built a whole design universeEverything you need to know about the Danish designer who brought modernism to the mainstream – and created some of the most recognisable buildings and objects of the 20th century

-

Meditations on Can Lis: Ferm Living unveils designs inspired by Jørn Utzon’s Mallorcan home

Meditations on Can Lis: Ferm Living unveils designs inspired by Jørn Utzon’s Mallorcan homeFerm Living’s S/S 2025 collection of furniture and home accessories balances Danish rationality with the elemental textures of Mallorcan craft

-

Carl Hansen & Søn reissues two masterpieces by Danish pioneer Kaare Klint

Carl Hansen & Søn reissues two masterpieces by Danish pioneer Kaare KlintDanish design powerhouse Carl Hansen & Søn presents a bed and chair originally designed in the 1930s by Kaare Klint, the founder of the Danish Modern movement

-

Tableau presents previously unseen Poul Gernes flower lamp

Tableau presents previously unseen Poul Gernes flower lampDanish design studio Tableau worked with the Poul Gernes Foundation to bring to life the design for the first time

-

The Danish shores meet East Coast America as Gubi and Noah unveil new summer collaboration

The Danish shores meet East Coast America as Gubi and Noah unveil new summer collaborationGubi x Noah is a new summer collaboration comprising a special colourful edition of Gubi’s outdoor lounge chair by Mathias Steen Rasmussen, and a five-piece beach-appropriate capsule collection

-

Reform kitchens’ New York showroom opens in Brooklyn

Reform kitchens’ New York showroom opens in BrooklynLocated in Dumbo, Reform kitchens’ New York showroom brings Scandinavian kitchen design to the American East Coast

-

3 Days of Design 2022: best of Danish design, and more

3 Days of Design 2022: best of Danish design, and moreExplore the best new spaces and furniture launches from Danish and international brands and designers at Copenhagen’s 3 Days of Design 2022

-

Danish studio Tableau takes flower arranging into uncharted waters

Danish studio Tableau takes flower arranging into uncharted watersWe talk to Tableau Copenhagen founder Julius Værnes Iversen on the studio's evolution from flower shop to fully-fledged design operation and its collaboration with artists, designers and design brands