How Arne Jacobsen built a whole design universe

Everything you need to know about the Danish designer who brought modernism to the mainstream – and created some of the most recognisable buildings and objects of the 20th century

Few designers have shaped both the skyline and the domestic landscape as profoundly as Arne Jacobsen (1902–71). The Danish architect and designer is remembered not only for modernist landmarks such as Copenhagen’s SAS Royal Hotel but also for furniture, lighting and objects that have become part of everyday life, from chairs to cutlery. More than half a century after their debut, Jacobsen’s designs continue to define the language of modern living – quietly radical in their time, yet still relevant today.

His design philosophy, centred on the concept of total design – a harmonious integration of architecture, furniture and interior elements, was guided by functionalism and simplicity, ensuring that it was accessible and enduring. He believed that form follows function, and that good design is essential to a good quality of life, emphasising proportion and the seamless combination of materials to create unified, human-centred environments. Now, as Prestel launches a new monograph exploring his work, we reflect on Jacobsen’s career and the events that shaped it.

Between architecture and design: who was Arne Jacobsen?

Jacobsen's early life and education

Born in 1902 into a middle-class Jewish family in Copenhagen, Jacobsen originally dreamed of becoming a painter. His father, a wholesaler, persuaded him to pursue the more stable path of architecture. After a stint as an apprentice stone mason, he enrolled at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1924, where he produced his first pieces of furniture. His professors included Kaare Klint, regarded as the father of Danish modernism, and Kay Fisker, one of Denmark’s leading functionalist architects, who instilled in Jacobsen a disciplined approach to proportion and material.

Aarhus Town Hall boasts a whole range of tables and chairs, fixed counters, wooden panel wallcoverings, signs, clocks, lighting, and more, all designed as a collaboration between Jacobsen, Møller, and Wegner

In 1925, aged just 23, Jacobsen worked with Fisker on the Danish pavilion for the Paris World Fair, where he won a silver medal for a wickerwork design known as the Paris Chair – an early example of his natural flair for sculptural form.

Paris chair by Arne Jacobsen

Family and travels

Two years later, Jacobsen married Marie Jelstrup Holm, with whom he had two sons, Johan and Niels. He established his own studio in 1929 and began to explore the idea of total design. Travels with Marie across Europe proved to be a rich source of inspiration: everywhere they went, Jacobsen painted watercolours and took experimental photographs, capturing the nature and architecture around them. These studies would continue to inform his practice throughout his career.

The wedding chamber at Aarhus Town Hall with the grey-painted chair-and-sofa series. In the background is the original wall decoration by Albert Naur of wild flowers painted directly on the wall, which also inspired Jacobsen’s textiles

Civic commissions and ‘total design’

In the early 1940s, Jacobsen completed two significant public buildings: Aarhus City Hall, designed with Erik Møller, and Søllerød Town Hall, in collaboration with Flemming Lassen. In both, the architects took responsibility for the interiors as well as the architecture – designing everything from furniture and lighting to bathroom fittings, door handles and signage. This holistic approach cemented Jacobsen’s reputation as a designer of complete environments.

It was during the Søllerød commission that Jacobsen met his second wife, Jonna Møller, a textile printer who produced fabrics for the project. They married in 1943 and developed a creative partnership, with Jonna helping to translate Jacobsen’s botanical studies and watercolours into textile patterns.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

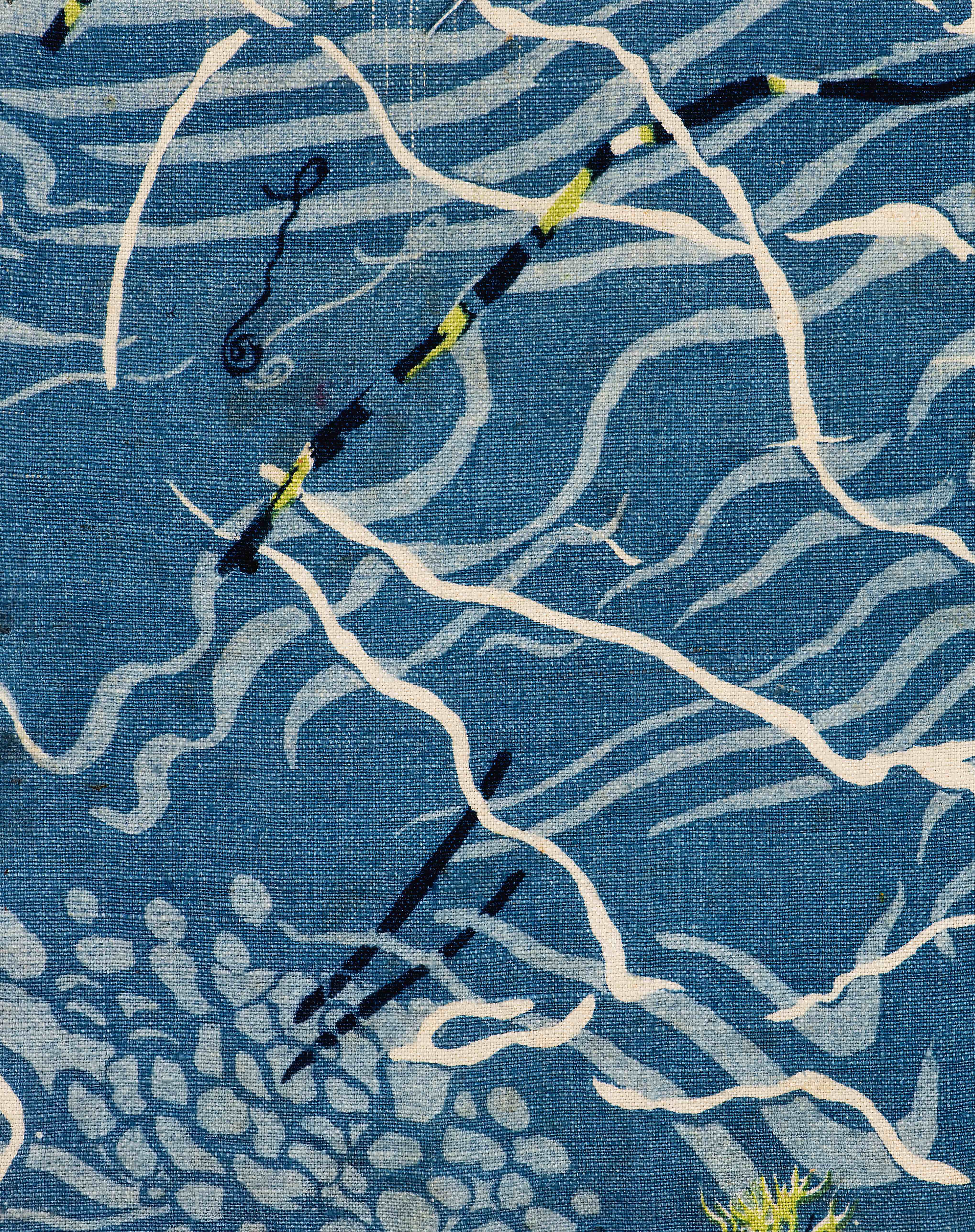

Arne and Jonna\s textiles evolved from the deeply figurative motifs towards the more abstract. The textile 'Water' was inspired by looking down over the waves. Produced for Textil Lassen

Jacobsen the botanist

That same year, as a Dane of Jewish descent, Jacobsen was forced to flee Nazi-occupied Denmark. He and Jonna lived in exile in Sweden until 1945, where their creative collaboration deepened. Jacobsen continued to paint botanical studies, many of which Jonna adapted into textiles that were put into production by Swedish department store Nordiska Kompaniet.

After returning to Denmark in 1945, the couple eventually settled at Strandvejen 413 in Klampenborg (1951), a home and studio Jacobsen designed for the family, complete with a botanical garden containing more than 300 plant species. His lifelong passion for botany inspired him to create buildings where architecture and nature are symbiotic, such as the Munkegaard School (1957), where every classroom opens onto its own garden, and St Catherine’s College in Oxford (1964), where he personally selected many of the trees and plantings to complement the modernist buildings.

The AJ cutlery produced by Georg Jensen was designed as an affordable and functional alternative to traditional silver cutlery

Arne Jacobsen's legacy

Jacobsen’s influence extends far beyond his lifetime. His architecture and furniture continue to be reissued, studied and celebrated as milestones of modern design. The Arne Jacobsen Foundation preserves his archive and supports research into his work, ensuring his philosophy of total design remains visible to new generations. More than half a century on, Jacobsen’s creations still shape the way we live – proving that clarity, simplicity and a respect for human experience never lose their relevance.

SAS Royal Hotel

Room 606 at the SAS Royal hotel has been restored to look like Jacobsen's original design

Jacobsen’s international breakthrough came with the SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen (1958–60), the world’s first design hotel. Commissioned by Scandinavian Airlines to symbolise postwar modernity and international travel, it was conceived as a 'gesamtkunstwerk' – a ‘total work of art’. Jacobsen designed not only the building but also the interiors, furniture and fittings – from the famous Egg and Swan chairs to cutlery, door handles and even ashtrays. While much of his interior scheme was later removed, Room 606 remains intact as a rare glimpse into his holistic vision, embodying his belief in complete, cohesive environments.

The SAS Royal Hotel photographed in 1960

Other works by Arne Jacobsen

Rødovre Town Hall (1952–56) was one of Jacobsen's first major public commissions. Here, he refined his modernist vocabulary into a civic context

Beyond the SAS Royal, Jacobsen left his mark on education, housing and civic buildings. Early residential projects such as the Bauhaus-inspired Bellavista housing complex north of Copenhagen (1934) showcased his embrace of clean lines, light and sea views, bringing functionalism into everyday life. The Søholm housing development (1951–55) in Copenhagen’s Klampenborg suburb further demonstrated his skill at designing humane, light-filled homes. At Rødovre Town Hall (1952–56), one of his first major public commissions, he refined his modernist vocabulary into a civic context, with a focus on details that bear the hallmarks of industrial manufacturing.

At St Catherine’s College, Oxford (1964), Jacobsen combined traditional and modern ideals

At Munkegaard School in Copenhagen (1957), he balanced architecture with landscape, weaving courtyards and gardens into the learning environment. At St Catherine’s College, Oxford (1964), his first major project abroad, he created a modernist campus where buildings, furniture, textiles and planting formed a seamless whole. Finally, the National Bank of Denmark in Copenhagen (1961–71) revealed the same rigour on a monumental civic scale, with refined proportions and meticulous detailing. His approach consistently blurred the line between architecture, interiors and nature.

7 Arne Jacobsen designs to know (and own)

Further reading

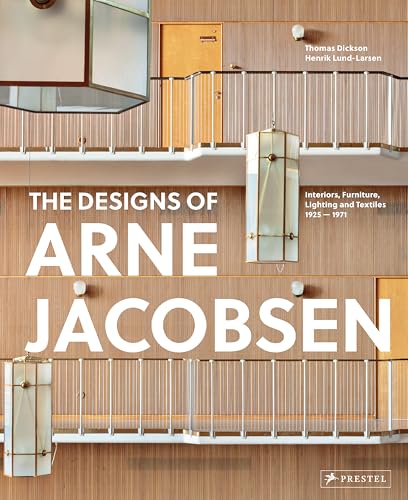

Out in September 2025, this new tome is the most comprehensive book on the designer, tracing Jacobsen’s career as from his early functional experiments to his most influential works in architecture, furniture and product

Ali Morris is a UK-based editor, writer and creative consultant specialising in design, interiors and architecture. In her 16 years as a design writer, Ali has travelled the world, crafting articles about creative projects, products, places and people for titles such as Dezeen, Wallpaper* and Kinfolk.

-

High in the Giant Mountains, this new chalet by edit! architects is perfect for snowy sojourns

High in the Giant Mountains, this new chalet by edit! architects is perfect for snowy sojournsIn the Czech Republic, Na Kukačkách is an elegant upgrade of the region's traditional chalet typology

-

'It offers us an escape, a route out of our own heads' – Adam Nathaniel Furman on public art

'It offers us an escape, a route out of our own heads' – Adam Nathaniel Furman on public artWe talk to Adam Nathaniel Furman on art in the public realm – and the important role of vibrancy, colour and the power of permanence in our urban environment

-

'I have always been interested in debasement as purification': Sam Lipp dissects the body in London

'I have always been interested in debasement as purification': Sam Lipp dissects the body in LondonSam Lipp rethinks traditional portraiture in 'Base', a new show at Soft Opening gallery, London

-

Meditations on Can Lis: Ferm Living unveils designs inspired by Jørn Utzon’s Mallorcan home

Meditations on Can Lis: Ferm Living unveils designs inspired by Jørn Utzon’s Mallorcan homeFerm Living’s S/S 2025 collection of furniture and home accessories balances Danish rationality with the elemental textures of Mallorcan craft

-

Tableau presents previously unseen Poul Gernes flower lamp

Tableau presents previously unseen Poul Gernes flower lampDanish design studio Tableau worked with the Poul Gernes Foundation to bring to life the design for the first time

-

The Danish shores meet East Coast America as Gubi and Noah unveil new summer collaboration

The Danish shores meet East Coast America as Gubi and Noah unveil new summer collaborationGubi x Noah is a new summer collaboration comprising a special colourful edition of Gubi’s outdoor lounge chair by Mathias Steen Rasmussen, and a five-piece beach-appropriate capsule collection

-

3 Days of Design 2023: best of Danish design, and more

3 Days of Design 2023: best of Danish design, and moreOur highlights from 3 Days of Design 2023: a city-wide programme of launches and exhibition by leading Danish and international design brands

-

Reform kitchens’ New York showroom opens in Brooklyn

Reform kitchens’ New York showroom opens in BrooklynLocated in Dumbo, Reform kitchens’ New York showroom brings Scandinavian kitchen design to the American East Coast

-

3 Days of Design 2022: best of Danish design, and more

3 Days of Design 2022: best of Danish design, and moreExplore the best new spaces and furniture launches from Danish and international brands and designers at Copenhagen’s 3 Days of Design 2022

-

Danish studio Tableau takes flower arranging into uncharted waters

Danish studio Tableau takes flower arranging into uncharted watersWe talk to Tableau Copenhagen founder Julius Værnes Iversen on the studio's evolution from flower shop to fully-fledged design operation and its collaboration with artists, designers and design brands

-

Talent and textiles come together in a new project by Kvadrat Febrik

Talent and textiles come together in a new project by Kvadrat Febrik28 emerging designers from around the world create furniture and objects using Kvadrat Febrick fabric range