Remembering master joiner Ejnar Pedersen (1923-2020)

Ejnar Pedersen, one of Danish midcentury modernism’s most prolific craftsmen, passed away last month, aged 97. To pay our respects, we bring you the following article, that was first published in the May 2014 issue of Wallpaper* (W*182)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

In a light-filled, open-plan living room in Hørsholm, a residential town on the Øresund coast some 30 minutes north of Copenhagen, the dining table has been immaculately set for two. It’s lunchtime on a Sunday. At the cooker, humming, stands Ejnar Pedersen, one of Danish midcentury modernism’s most prolific craftsmen and, at 91, one of its last.

‘Sit down, sweet one,’ he says, approaching with a steaming cast-iron pot in one hand, and pointing with the other to a Hans Wegner ‘Chinese Chair’. We take our seats and start on the soup, a brothy mélange of vegetables and micro-meatballs. Three variations of herring sit waiting in their porcelain dishes.

I’ve been invited for lunch to discuss Pedersen’s forthcoming book, A Life Well Crafted, which is an autobiographical tell-all about the inception and rise of Danish modernism and, though he would never admit it, Pedersen’s pivotal role in its enduring legacy.

The ‘EP’ makeup table and vanity box, at Pedersen’s home in Hørsholm. It was designed by his longtime partner Hanne Kjærholm in 2004 and created in mahogany and brushed steel by Pedersen at PP Møbler.

Indeed, as the founder of PP Møbler, one of the most respected of the furniture manufacturers associated with the Danish modernist movement, Pedersen worked side by side with some of the leading architects and designers of the time: Hans Wegner, Poul Kjærholm, Finn Juhl, Arne Jacobsen and Verner Panton among them. What they drew, or dreamed of, Pedersen helped turn into a functional reality.

‘I’m just a happy cabinetmaker who happened to get very lucky and work with some of the best,’ Pedersen says, shrugging. I suggest that perhaps it wasn’t luck. He changes the subject. ‘My favourite wood is ash, the light one,’ he says, looking at the pristine floorboards underfoot, ‘but I’m also very fond of maple. The truth is that I’ve never really come across a piece of wood I don’t like – so long as it’s untreated.’ Pedersen recalls that a radio journalist once asked him why he never lacquered any of the furniture he produced. ‘I told him I felt the same way about my wood and my women: they’re best when kept natural – too much polish and they age too quickly, so just stick to soap and water.’

He’s unable to contain a smirk, and sure enough, it doesn’t take long to uncover that there have been four great loves in Pedersen’s life. One being his craft, the other three, women: Kirsten, his late wife, and mother to his two children; ‘Ten years Birthe’, as he affectionately refers to a decade-long relationship with a woman of that name during his middle age; and then there was the architect Hanne Kjærholm, his girlfriend for 28 years, until her death four years ago.

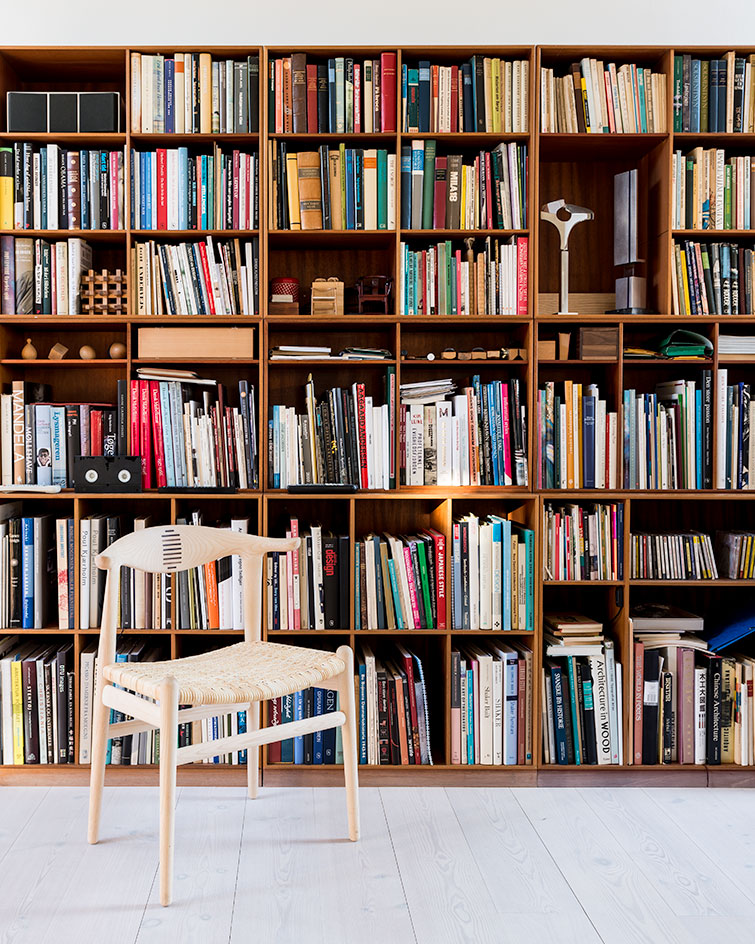

Also at Pedersen’s home, besides shelves by the celebrated Danish architect and designer Mogens Koch, one of the smaller Hans Wegner chairs, the ‘Cow Horn Chair’, carved at PP Møbler. The joint in the backrest is made a feature by the use of contrasting wood.

‘I have been so lucky with the wonderful women in my life,’ says Pedersen, who seems to reflect on just about everything with an earnest sense of gratitude. ‘To think that a little joiner from the country like me met all these wonderful people along the way.’

Born in 1923 in Vejen, a small town in the rural south of mainland Jutland, Pedersen was raised in a working-class home where religion, socialism and monarchism happily co-existed. At 14, he was sent, reluctantly, to work at the local joinery workshop, Willadsen.

‘I thought it was awful, the wood seemed to hate me, and I it, but the alternative was farming, which I thought was an even less appealing option,’ says Pedersen. ‘So I stuck with it, and that’s how I became a cabinetmaker and, eventually, a very happy one.’

Frames, legs and backs in the store room at PP Møbler.

Pedersen finished his apprenticeship in 1943 and moved to Copenhagen, where he worked at AJ Iversen, then the country’s most respected furniture manufacturer, before setting up shop with Knud Willadsen, the son of his old master, back in Vejen. They got a successful workshop up and running, and quickly became established in the furniture trade.

A turning point came in 1951 when the two joined forces with artist Gunnar Aagaard Andersen and architects Nanna and Jørgen Ditzel to put on the exhibition ‘Wood, Form and Colour: A Cabinetmaker’s Collaboration with Artists’, at Winkel & Magnussen, an art dealer and auction house in Copenhagen. The ambition was to rebel against traditional rules of interior decoration and present new ideas about how to furnish the modern home. It was all about clean lines and minimalism, new materials and unexpected woods.

Wegner (left) and Pedersen pictured at the workshop in 1980, inspecting an example of the ‘Chinese Chair’ (1945).

‘It was a taste of what was to come, of what was possible when architects and cabinetmakers joined forces, worked together, listened to one another,’ says Pedersen. While critics snubbed the exhibition as youthful experimentation that had no staying power, enthusiasts heralded it as a look into the future, a sign of changing times and modernism coming to Denmark.

The next morning we meet at the PP Møbler workshop in Allerød, a sleepy industrial municipality that was once the hotbed for the Danish furniture trade. PP sits as a sort of enduring relic on the same plot of land where it first opened in 1953 – of the few workshops that remain, it’s one of the tiny number that still produces everything on-site. Dressed in jeans, a grey cashmere jumper and sensible shoes, Pedersen is a robust figure with feathery white hair and a matching beard. He winds his way through the workshop, stopping at various workstations to check up on the chairs in progress.

Although he handed the day-to-day operations of PP over to his son, Søren, in 2000, Pedersen still spends three or four days a week at the workshop: ‘I can’t quite break the habit after 60 years,’ he says. Pedersen founded PP with his older brother, Lars Peder, also a cabinetmaker, just as modernism was taking hold in Danish households, which were enjoying the relative prosperity that came with the budding welfare state.

‘It was a time of experimentation and rebellion in the furniture trade – out with the establishment, in with a new way of thinking,’ says Pedersen, ‘and no one captured that way of thinking quite like Poul Kjærholm.’ A Bauhaus-inspired functionalist who rebelled against the Danish tradition of woodwork, preferring instead to experiment with leather, steel and glass, Kjærholm became one of Pedersen’s close friends and collaborators.

Their partnership began when they developed an extension ring for Kjærholm’s ‘PK54’ table, made up of six, marvellous maple leaves that are inserted and seamlessly interlinked around the 200kg, round marble (or granite) slab, balanced on top of a delicate steel cube. ‘It is unquestionably the world’s most beautiful dining table’, says Pedersen. Most famously, they worked together to design and craft the chairs for the Vilhelm Wohlert-designed concert hall at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, a space that became an icon of Danish design. Their partnership was cut short, however, when lung cancer struck down Kjærholm in 1980, at the age of 51.

In the later stages of production at PP Møbler, the ‘Chinese Bench’, the ‘Rocking Chair’, and the ‘Circle Chair’, all by Hans Wegner.

It was some years later that Pedersen and Hanne Kjærholm, Poul’s widow, became a couple. What had begun as friendship had blossomed into romance. I ask Pedersen if there are other Kjærholm pieces that he holds particularly dear.

The ‘PK9’ chair was born of Hanne Kjærholm asking her husband to make a seat that would ergonomically fit a woman’s entire backside. The result is as sculptural as it is functional, all hips and waist atop a three-pronged steel base. We come to rest in front of a very different chair, simply known as ‘The Chair’. A slender, modest Hans Wegner model that epitomises the tradition of Danish woodwork, it was made famous in 1960 when it appeared as seating in the first-ever televised US presidential election debate between Kennedy and Nixon.

‘We spent years as subcontractors to his bigger producers, but in the 1960s Wegner himself came knocking,’ says Pedersen. ‘By then he was already a star on the furniture scene, and it was a real vote of confidence to find him suddenly standing on our workshop floor.’ Wegner offered PP the rights to two chairs, and it marked the workshop’s next chapter. Many more models would follow, and today, PP manufactures the majority of Wegner’s designs: from the exclusive and stately ‘Papa Bear’ to the exquisite ‘Circle Chair’ – with its intricately woven flagline back, it’s a true peacock of a seat.

‘Wegner wasn’t just an architect, he was one of the finest craftsmen Denmark has ever seen; he understood wood better than most,’ says Pedersen. ‘He could be difficult, a particular man, but he was prolifically productive, leaving some 1,000 designs to his name.’

I’m just a happy cabinetmaker who happened to get very lucky and work with some of the best

Indeed, many famous names and faces passed through the PP workshop over the years – Verner Panton always came round with ideas to develop prototypes, and Arne Jacobsen called about a particularly difficult shelving project. But Wegner and Kjærholm were the regulars, the two architects standing amidst the joiners in the sawdust.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

A post shared by PP Møbler (@ppmobler)

A photo posted by on

I ask Pedersen why he thinks their designs have remained so relevant, still coveted not just by an architectural elite, but by diverse international audiences. Why is the Danish modern aesthetic simultaneously cool enough for the hip, discreet enough for the refined, prestigious enough for the ostentatious, and principled enough for the high-minded? ‘When you cut down to the bone, you take away excess, that’s when things become timeless. They last for generations, they’re passed down,’ says Pedersen. ‘These things come into existence when there is an open dialogue between architect and joiner. When the architect’s eye and the joiner’s hands connect, you make soulful objects that have purpose, both in terms of function and aesthetic.’

Finally, perhaps inadvertently, Pedersen gives himself a bit of credit. Our tour of the workshop is coming to an end when a young man with two full sleeves of tattoos places Wegner’s ‘Tub Chair’ in front of Pedersen for inspection. A slender, elegant piece, the chair never went into production, but is now entering the official PP line-up. It was being shot on the day of my visit for promotional materials for a PP exhibition during the Salone del Mobile, in celebration of Wegner’s 100th birthday in April 2014.

‘See, now I think we’ve got the joints just right,’ says the young man, ‘and we’re going to put some lacquer on it before it goes upstairs to be photographed.’ ‘Like hell you are,’ replies Pedersen. True to form, we don’t linger and Pedersen walks me to the door. He hugs me, says goodbye, and with that, the happy cabinetmaker disappears back inside the workshop – back to his Wegner, his wood and his women.

A version of this article originally featured in the May 2014 issue of Wallpaper* (W*182)