Exploring Night Fever at Vitra Design Museum

Dry ice, block rockin’ beats and a DJ booth elevated on high from a Konstantin Grcic pimped up Smart car… the preview of ‘Night Fever: Designing Club Culture 1960-Today’ wasn’t your average exhibition launch. But then the subject matter is as visceral as it is theoretical. Indeed, few exhibitions are likely to inspire as much instantaneous joy and nostalgia than this, debuting at the Vitra Design Museum.

Attempting to capture snapshots of an ephemeral phenomenon is brave, but encapsulating recent folk history is also a canny move. Reminding people how they tripped the light fantastic during their late teens and twenties – the most liberating decades of anyone’s life – Night Fever surely has crowd-pleasing blockbuster written all over it. Something that didn’t escape the trio of curators, Jochen Eisenbrand (Vitra Design Museum), Catharine Rossi (Kingston University London) and Katarina Serulus (ADAM - Brussels Design Museum). Vitra museum director Mateo Kries put it succinctly when he said: ‘Few other topics speak so directly to a museum visitor and recall such intense memories and feelings. We all remember experiencing nightlife, a place where you had the most memorable moments with music and dancing.’

The entrance to the Night Fever exhibition and The Palladium in New York, 1985 by architect Arata Isozaki with a mural by the late pop artist Keith Haring| Simon Gallery New York

Beyond this rose-tinted reminiscing though, there is depth. Nightclub design is not just a superficial glitterball of a topic that only deserves to shine after dark. It projects a kaleidscope of reflections, which in their fleeting spontaneity can reveal much about how we live. (As French semiotician Roland Barthes recognised when he penned his 1978 essay on Paris’s Le Palace club.) What makes nocturnal adventures in clubland so appealing, from an immersive perspective and as subjective museum fodder, is its deeply entrenched love affair with the avant-garde, creativity and experimentation (something I explored in my 2002 book Bar & Club Design; Laurence King).

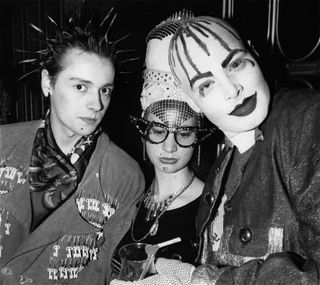

Clubs are liberating spaces where playing with identity and self-expression through dress, music, dance and drugs is encouraged by equally outré, theatrical or radical interiors and graphics. ‘Design here is about not about sharing an object,’ Kries added, ‘it’s about sharing moments and experiences. Clubs often reflect changes in society, and are a condensed image of what happens in society.’ What’s more, short-lived throwaway nocturnal spaces are often where the designers of tomorrow hone their skills.

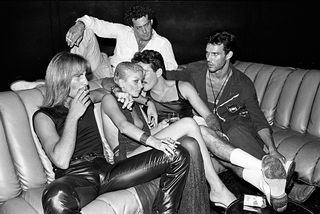

Guests in conversation on a De Sede DS 600 sofa, Studio 54, New York 1979

Compiling ‘Night Fever’ wasn’t easy, it’s still relatively unexplored territory and much of the information presented here is compiled from aural histories. Loans came from just three institutions; the majority of items were contributed by individuals – 50 in total from architects, designers, DJs and die-hard devotees (and memorabilia collectors) of legendary clubs like Manchester’s Haçienda (the frenzied fandom of which is revealed in a documentary of those who bought fragments of the club when it was auctioned off) New York’s Studio 54 and The Paradise Garage.

DJ Larry Levan and The Paradise Garage, New York play a starring role in the Night Fever exhibition

Strangely, Ibiza doesn’t feature, but as co-curator Catharine Rossi says, ‘We don’t pretend its comprehensive that would be impossible, but we recognise it is a global story. Every culture creates its own nightlife, sealed off spaces that are heterotopian places where you can go and be who you want to be.’ The excellent accompanying catalogue is more extensive and packed with interesting essays and interviews with DJs and club operators.

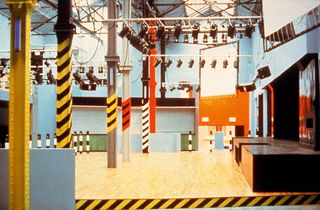

An evening at Space Electronic, Florence 1971. Design Gruppo 9999.

Wisely eschewing the temptation to recreate an actual club environment (it was initially muted) the exhibition is arranged chronologically through four exhibition halls, each named after pop and rock songs with seminal venues presented as case studies throughout to tell the story. Hall 1, Beginning to See the Light, explores the 1960s and how nightclubs such as New York’s fantastically named The Electric Circus (1967), Florence’s Space Electronic (1969) and Munich’s Yellow Submarine (1971) emerged alongside new counter cultures and alternative lifestyles. There is a particular focus on here Italian clubs associated with Italy’s Radical Design movement. Materials on display range from poster graphics, photography, magazine articles, film and furniture, including a discotastic chair by Gufram.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

Visitors get lost in music in Konstantin Grcic and Matthias Singer’s immersive installation.

Neon signs replicating club logos, industrial structural elements, film footage and the use of blown-up photography effectively bring the topic to life, but it’s Hall 2 – Can you feel it? – where visitors will immerse themselves and get lost in music. Konstantin Grcic and lighting designer Matthias Singer’s interactive installation takes the form of a mirrored booth lined with a grid of multi-coloured neon lighting that pulsates, reflecting into infinity. It’s Justin Timberlake’s Rock your Body video meets silent disco. Headphones suspended from the ceiling enable visitors to plug into four distinct decades and music genres: pre-disco, disco, house and techno. The playlists are spot on; House features Frankie Knuckles Tears, Mr Fingers Can you feel it? and Phuture’s Acid Tracks.

Hall 3 features John Travolta, Night Fever at the Vitra Design Museum

The euphoric mood climaxes with disco and Slave to the Rhythm (Hall 3), signposted by a giant screen playing John Travolta’s mesmerising Saturday Night Fever dance routine on loop. Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell’s Studio 54 is the undeniable star here, dazzling hand-in-hand with dancefloor partners – celebrity culture and fashion. This is when clubbing transformed into a decadent performance art of its own, with the venues of the Seventies and Eighties occupying old theatres, cinemas and film studios, encouraging the see-and-be-seen ethos.

We follow its inevitable commercialisation as it gives way to the new edgier, grungier House music scene, initially fuelled by gay subculture and rising up from the post-industrial landscape of American – represented here by The Paradise Garage and later in the UK Ben Kelly’s Haçienda. Rave culture gets a look in too as part of Mark Leckey’s brilliantly evocative short film Fiorucci Made me Hardcore (1999) and this was surely the age of the inventive flier, as proven by examples from the UK Acid House and the 1990s club scene.

Inside the Haçienda, Manchester.

Around the World concludes Night Fever, charting the flourishing of techno in the vast vacant buildings of post-wall Berlin, while also documenting the widespread demise of the nightclub and the emergence of the commercialised global club brand. London’s Ministry of Sound is highlighted for its diversification into other lifestyle arenas – namely work (with new co-working spaces) and leisure (gyms) – catering to changes in social behaviour in order to survive.

We look to the future, as the urban nightclub wanes, it’s superseded by open-air music festivals and pop-up clubs, with case studies including Carsten Höller’s club for Prada, Assemble’s Newcastle stage for Belgium’s Horst festival and incredible Brazilian sound systems. There is less here about the club goer and more focus on architectural models and the technology, from sound systems to the turntables of choice.

Trojan, Nichola and Leigh Bowery at London club Taboo, 1985.

For those who hark back to the clubbing heydays of the 1970s, 80s and 90s that felt such fertile, anarchic places for youth subcultures and alternative identities to thrive – this denouement feels like a bit of a comedown. However, if anything Night Fever demonstrates that although the clubs of yesteryear may become the luxury flats of tomorrow, people will always seek music-fuelled escapism en masse and these spaces will continue to mutate (note that illegal raves have increased in recent years).

Meanwhile, designers and artists continue to flirt with hedonistic spaces; last year Carsten Höller’s The Prada Double Club pop-up was the highlight of Design Miami and this year’s Salone del Mobile promises to be the year of the club with a renewed interest in creating after-dark spaces from India Mahdavi’s Chez Nina private club for Nilufar to Disco Gufram, from Studiopepe’s Club Unseen to Lasvit’s Cabaret.

For the art and design community at least, night fever continues to burn, baby burn and for that we salute them.

Akoaki, Mobile DJ Booth, The Mothership, Detroit, 2014 features in the final hall of the exhibition.

Newcastle stage at Horst Arts & Music Festival, Belgium, 2017 designed by Assemble architects.

INFORMATION

‘Night Fever: Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today’ is on view until 9 September, after which the exhibition will travel to Belgium. For more information visit the Vitra Design Museum website

-

The Eurovision stage for 2024 has been unveiled

The Eurovision stage for 2024 has been unveiledThis year's stage design aims to bring the audience into the performance more than ever before.

By Charlotte Gunn Published

-

Ikea meets Japan in this new pattern-filled collection

Ikea meets Japan in this new pattern-filled collectionNew Ikea Sötrönn collection by Japanese artist Hiroko Takahashi brings Japan and Scandinavia together in a pattern-filled, joyful range for the home

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

Coming soon: a curated collection of all the new EVs and hybrids that matter

Coming soon: a curated collection of all the new EVs and hybrids that matterWe've rounded up new and updated offerings from Audi, Porsche, Ineos, Mini and more to keep tabs on the shifting sands of the mainstream car market

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

Faye Toogood brings new life to Matisse’s legacy

Faye Toogood brings new life to Matisse’s legacyMilan Design Week 2023: tapped by Maison Matisse, the London-based designer has taken inspiration from the French master’s forms to create a collection of heirloom-worthy objects

By Sam Rogers Published

-

Prada Frames 2023: Milan programme announced

Prada Frames 2023: Milan programme announcedProgramme announced for Prada Frames 2023 at Milan Design Week, the annual symposium curated by Formafantasma at Luigi Caccia Dominioni's Teatro Filodrammatici from 17 to 19 April

By Rosa Bertoli Last updated

-

Alessi Occasional Objects: Virgil Abloh’s take on cutlery

Alessi Occasional Objects: Virgil Abloh’s take on cutleryBest Cross Pollination: Alessi's cutlery by the late designer Virgil Abloh, in collaboration with his London studio Alaska Alaska, is awarded at the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2023

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

Salone del Mobile 2023: highlights from Milan Design Week

Salone del Mobile 2023: highlights from Milan Design WeekIn pictures: our highlights from Milan Design Week, held during the 61st Salone del Mobile 2023 (18-23 April)

By Rosa Bertoli Last updated

-

Nendo’s collaborations with Kyoto artisans go on view in New York

Nendo’s collaborations with Kyoto artisans go on view in New York‘Nendo sees Kyoto’ is on view at Friedman Benda (until 15 October 2022), showcasing the design studio's collaboration with six artisans specialised in ancient Japanese crafts

By Pei-Ru Keh Last updated

-

USM launches blushing pink limited edition of its modular furniture

USM launches blushing pink limited edition of its modular furnitureFollowing an installation during Milan Design Week 2022, USM launches a new pink limited edition of its Haller range

By Rosa Bertoli Last updated

-

Italian craftsmanship comes to Los Angeles in this eclectic Venice Canals apartment

Italian craftsmanship comes to Los Angeles in this eclectic Venice Canals apartmentBoffi Los Angeles celebrates a juxtaposition of texture throughout a waterside bolthole

By Hannah Silver Last updated

-

Design Miami/Basel 2022 explores the Golden Age

Design Miami/Basel 2022 explores the Golden AgeDesign Miami/Basel 2022, led by curatorial director Maria Cristina Didero, offers a positive spin after the unprecedented times of the pandemic, and looks at the history and spirit of design

By Rosa Bertoli Last updated