Alexander Wessely turns the Nobel Prize ceremony into a live artwork

For the first time, the Nobel Prize banquet has been reimagined as a live artwork. Swedish-Greek artist and scenographer Alexander Wessely speaks to Wallpaper* about creating a three-act meditation on light inside Stockholm City Hall

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

For more than a decade, Alexander Wessely has moved fluidly between worlds – from his early years roaming the streets of Stockholm in the 1990s, absorbed in graffiti and drawing, through photography and film, to the sculptural installations and large-scale scenography that now define his work. His visual language tends toward the monumental: strobes, towering forms, extreme contrast and a distinctly ritualistic energy typify his work, staged everywhere from concert halls to the global pop arena, including projects with artists such as The Weeknd, FKA Twigs and Swedish House Mafia.

Now, that sensibility enters an unexpected setting. For the first time in its history, the Nobel Prize ceremony (held 10 December 2025) was reimagined through a contemporary artist’s lens, with Wessely given rare freedom to reshape the banquet inside Stockholm City Hall. His response – a three-act meditation on light, atmosphere and human progress – marked a striking departure for both the artist and the institution.

Ahead of the ceremony, Wallpaper* spoke with Wessely about the origins of the project, the process behind it, and the ideas that shaped this unprecedented commission.

Wallpaper*: How did this project first come about? It’s a new direction for you and something unprecedented for the Nobel Prize.

Alexander Wessely: It came through Jacob Mühlrad, the composer. He introduced me to the Nobel Foundation earlier this year, and we started talking about the possibility of this and what it could potentially be.

It’s very exciting. And like you said, in one way it’s quite a different scenario for me to be in, and in another way it’s the same thing as usual – music and light.

W*: When you first received that introduction, was there any kind of brief or structure? Or were you given a blank canvas?

AW: It was pretty much a blank canvas. They gave me creative freedom to approach it however I saw it. Jacob sent me the initial music, and I’ve been working with him previously – we’ve done things at the Royal Dramatic Theatre here in Sweden, at Berwaldhallen, and a couple of things of that nature.

We’ve invited each other into our [respective] worlds over the years, and I’m very gravitated towards his music – the sort of ritualistic tone of it, the serious nature of it, but with that glimpse of hope. It aligns very well with what I do.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

I received the music and went to Athens, my second home in Greece, and lived with it for almost three weeks. I started writing the ideas and then came back to Sweden, sat down with the team, and started building out this narrative and this world and what it could be.

‘I always want to put things on the very tip and push them to the edge, but I also want to respect the context’

Alexander Wessely

W*: When you’re living with the music like that, do visuals arrive quickly? Or is it more gradual?

AW: Yes and no. It does come, but sometimes I have to hold myself back a bit. It’s a fine balance – especially in a context like this. I always want to put things on the very tip and push it to the edge, but I also want to respect the context.

I’m a big user of strobes and very strong, heavy lights and extremely dynamic, high-impact visuals. But with live TV and with the Nobel context in general, I needed to hold that side of me back and invite viewers into a more roomy, dynamic journey – something more pulsation-driven, softer, wrapping people in the experience instead of them just looking at a wall over there.

W*: And the performance unfolds across three acts?

AW: Yes. The first act is an emulation of a sunrise – a dusky silhouette, a hard, almost dystopic introduction, like a new beginning.

Then, in the second act, we introduce another element: a light pillar. It’s basically a laser pillar, a physical object in the centre of the stage shooting up towards the sky.

In the third act, we introduce projection. We have multiple projectors mapping the room to create a surreal situation where I hope people start to wonder what’s real and what’s not – what’s physical and what’s digital. Because I really want to play with atmosphere. We have heavy smoke pouring out of the windows, creating emulations of fog or waterfalls. Blending the physical and the digital really intrigues me. I want people questioning what they’re actually looking at.

‘The idea might start with seven elements, and then we sit down, take it in, peel it back, peel it back, until it’s balanced’

Alexander Wessely

W*: You had a live audience in the room, but also a global televised audience. How did that shape the staging?

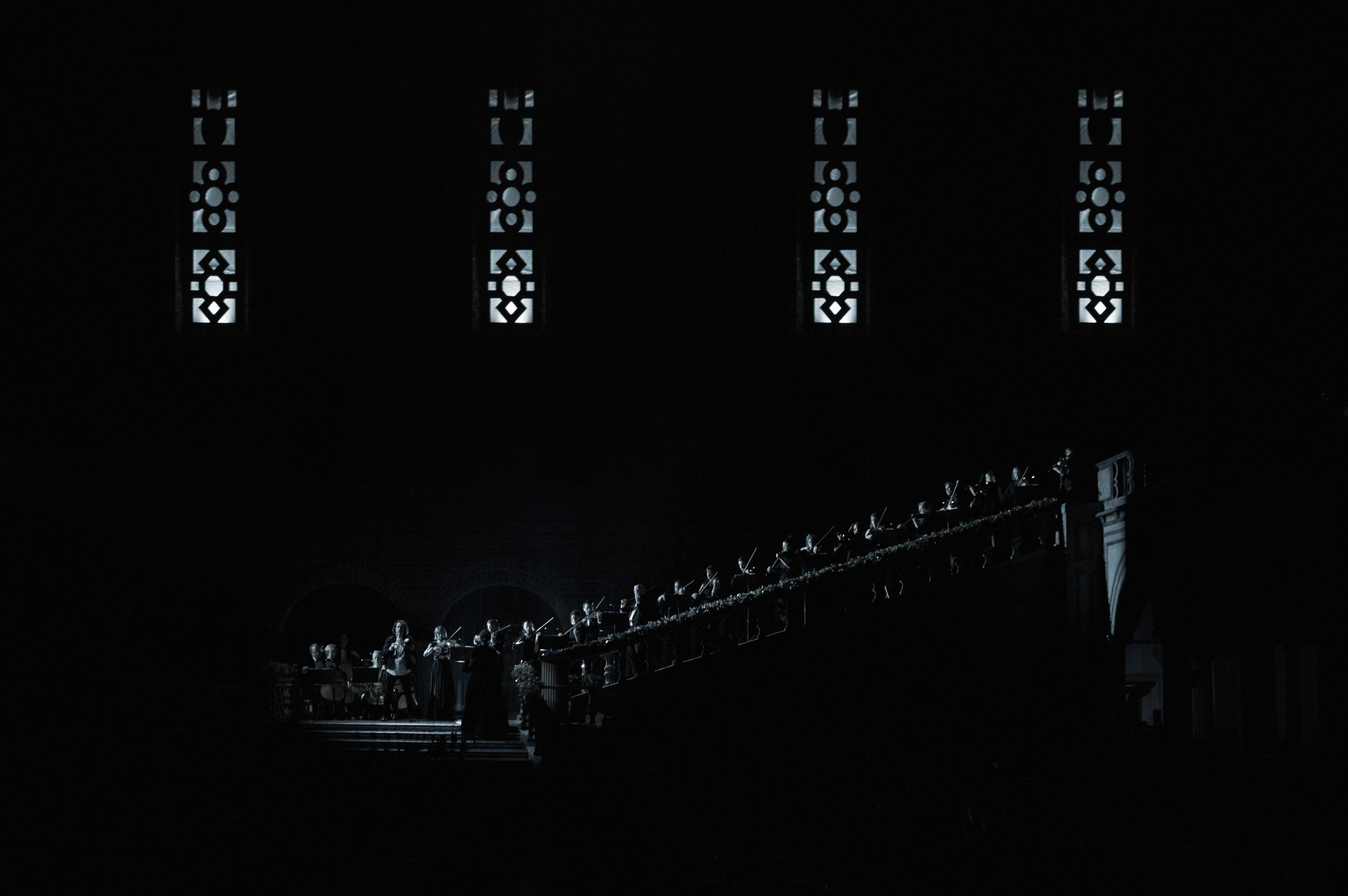

AW: It’s broadcast live, and there are around 2,000 people in the hall. The performance takes place in front of this huge staircase and along the long floor, with the audience sitting at tables on either side.

They’re looking in one direction, but the experience takes place from the sides and the front. As the evening goes on, they start to feel themselves immersed more and more into it – as we add atmosphere, introduce projection and so on.

W*: And Stockholm City Hall itself – did the space influence what you could or couldn’t do?

AW: It’s a sacral, almost church-like architecture, and that plays a role in a lot of my work. We’re in a 150-year-old building with these 30m ceilings, beautiful stone and brick, huge painted-glass windows.

The space is interesting in itself and in a lot of ways makes my work easier – at least with what I want to accomplish – because just placing a light pillar in the centre of this space becomes surreal in itself.

It’s almost like a cheat code, because the room is already so good. At the same time it sets boundaries, because it’s perfect already in many ways, so adding to it is complex. That’s why I keep it minimal in a purposeful way. The idea might start with seven elements, and then we sit down, take it in, peel it back, peel it back, until it’s balanced.

‘Blending the physical and the digital really intrigues me. I want people questioning what they’re actually looking at.’

Alexander Wessely

W*: Is peeling things back – reducing the idea to its core – your usual design process?

AW: Yes. It can be the biggest, most advanced space with 50,000 people, but I love the idea of pushing it to its core. Rather than having all of these things, what can we accomplish with, for instance, one strong beam from this direction, mimicking the sun?

I’m fascinated by how powerful one light source can be when you push atmosphere into the space with haze and smoke. And you actually made me think about that, because I realised it’s the same approach I had in a sculpture exhibition I did a couple of years ago at Fotografiska in Sweden. That whole exploration was about peeling back the layers of the human – exposing the purest form of what we are.

This is the same. Bring it back down. Strip away the extra things. Keep the purest form.

W*: Working in such a charged architectural space – does that make the process more enjoyable, or more challenging?

AW: Right now in my life and career, I enjoy this more. Maybe because it’s more challenging. There are more restrictions – the building is protected, you can’t hang things wherever you want, things are fragile, it’s not flexible.

In a stadium, you have a blank canvas. Here, the architecture is already a beautiful piece of art. That makes it more complex, but also more intriguing.

‘I’d rather hear someone say it’s shit and explain why than have everyone think it’s just “cool” or “good”’

Alexander Wessely

W*: You mentioned the installation period is very tight. What does this final stretch feel like for you?

AW: We’re in the studio working almost 24/7, making sure everything is correct and still doing some trial and error. We start building on Sunday (7 December 2025) evening – about four days before the ceremony.

I’ve become good at handling stress, which is probably not a good thing, because I don’t feel it, but I know it’s inside me. I’m never stressed about what the audience will think. As long as I’m happy and proud of the work we did, then it’s happy days for me.

W*: And when everything finally comes to life – do you get a sense of excitement from seeing something that began in your head become real?

AW: Yes. That’s still the driving factor. Seeing it come alive is the rewarding part. Then the dark part arrives quickly. Months or years of work are over after 60 or 90 minutes, and a big black hole opens up. It’s empty. And then it’s on to the next, in a weird way.

‘Seeing it come alive is the rewarding part. Then the dark part arrives quickly. Months or years of work are over after 60 or 90 minutes, and a big black hole opens up. It’s empty. And then it’s on to the next, in a weird way’

Alexander Wessely

W*: You said earlier that you don’t mind whether people ‘like’ it or not. When you’re designing, do you still hope to make people feel something specific?

AW: I’m very intrigued by making people question what’s real and what’s not – this sort of existential terror. I feel I want to ignite something inside the audience, whatever it might be.

I love the idea of people leaving with extremely different opinions. Not one aligned reality. I’d rather hear someone say it’s shit and explain why than have everyone think it’s just cool or good.

W*: Do projects like this continue to inform what comes next? Do elements carry forward into future work?

AW: Yes. I’m bringing in a couple of projection elements I used at Museu del Disseny in Barcelona. Some things from Berwaldhallen [concert hall in Sweden] are in here too. And then there are new elements.

I’ll most likely condense what felt best and bring that into the next project. It’s like a never-ending puzzle. I’ve always collected things – postcards when I was young, vintage watches from the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s later on. Time fascinates me a lot.

I feel a career is like collecting. You add experiences, ideas, thoughts. You can remove things from the collection and add new ones. That’s how I approach projects. I look into my mental collection, apply things, and add new pieces, remove old ones.

‘I feel a career is like collecting. You add experiences, ideas, thoughts. You can remove things from the collection and add new ones. That’s how I approach projects. I look into my mental collection, apply things, and add new pieces, remove old ones’

Alexander Wessely

W*: So there’s no grand career plan – it’s more about following what feels right next?

AW: Exactly. It’s terrible in a way. Since I was about 20, I’ve had this feeling everything is going to go to shit. When I reach certain milestones, I reboot.

With photography, when I reached certain points, I said: OK, let’s stop. Let’s investigate film. I did the same again. Then creative direction and art.

What’s stuck so far is having one leg in the cultural institutional space and one leg in pop culture and commercial space. That balance suits me – I get easily bored, so I need to challenge myself.

W*: So after working on something monumental, you might go in the opposite direction – do something completely different, something much smaller in scale, like a sculpture?

AW: Yes. I will. It’s like, when I’m standing in Mexico City at four in the morning looking at this huge skeleton of a production and thinking, why am I doing this? What’s the purpose? I go back to the hotel and fall back on that idea – me in a monastery in central Greece, close to Meteora, sculpting, and I get calm.

That’s the light at the end of the tunnel. Even though I love what I do, I sometimes really question the purpose of it, but then I can see the impact it makes on thousands of people. It makes me feel good for a bit – and then it’s on to the next. It’s interesting.

Ali Morris is a UK-based editor, writer and creative consultant specialising in design, interiors and architecture. In her 16 years as a design writer, Ali has travelled the world, crafting articles about creative projects, products, places and people for titles such as Dezeen, Wallpaper* and Kinfolk.