Inside Helmut Lang’s fashion archive in Vienna, which still defines how we dress today

New exhibition ‘Séance de Travail 1986-2005’ at MAK in Vienna puts Helmut Lang’s extraordinary fashion archive on view for the first time, capturing the Austrian designer-turned-artist’s enduring legacy

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

‘Looking at Helmut Lang’s store architecture, it became obvious: his stores were all about directing the gaze. This is also what exhibitions need to do, but here it was essential. A photo wouldn’t suffice; you have to experience it,’ says Marlies Wirth, curator of ‘Helmut Lang: Séance de Travail 1986-2005’, the first retrospective of the Austrian designer’s oeuvre, now open at Vienna’s Museum of Applied Arts (MAK).

It is a statement that encapsulates the extraordinary precision and intelligence behind Helmut Lang, who shaped the look of modern fashion in the 1990s with his cool, razor-sharp minimalism and continues to influence today (he is one of contemporary fashion’s most oft-referenced designers, alongside Martin Margiela). In MAK, every detail of the space has been choreographed to immerse visitors in his world: even the floor itself maps the layout and name tags of front-row guests – from Isabella Blow to Edward Enninful – of a runway show, or ‘Séance de Travail’, as Lang liked to call them.

‘Helmut Lang: Séance de Travail 1986-2005’, exhibition view. Excerpts from the MAK Helmut Lang Archive

‘Here is another European designer who literally brought the water to the well… of course I had an out-of-body experience at a Helmut Lang show,’ says the late Vogue editor Andre Leon Talley in an archival interview, discussing Lang’s A/W 2002 collection, that plays in one exhibition room. Another is filled with screens showing rare runway footage, backstage fittings, and further interviews, including with Lang himself. It is clear from the display that identity, for him, was a gradient: a man could wear a transparent shirt; a woman could wear sharply tailored, clean-cut, menswear-inspired jackets. There is an almost architectural discipline to the work: lean, aerodynamic lines run throughout, and silhouettes feel sliced in a single decisive gesture.

‘He didn’t formally study fashion,’ Wirth continues. ‘He grew up in the countryside; his grandfather was a shoemaker. He was exposed early on to workwear and utility wear, and said in interviews that he was fascinated by how things make sense when you understand their purpose. If a shoe looks a certain way because it needs to function, you understand the logic.’

Helmut Lang, test print of an advertisement, Helmut Lang Collection Hommes Femmes Séance de Travail # Été 03 (2002)

This is clear from some of the garments in the archive, like the ‘Astro Biker Jacket’ from the A/W 1999 collection, which combines elements of classic motorcycle gear with references to astronautics and aeronautical engineering. Its metallic finish feels almost extraterrestrial, while concealed straps and a foldaway harness – meant to be worn on the back when the jacket isn’t being worn – give it Lang’s signature mix of futurism and functionality. Alongside his practical designs, he drew on images, such as Robert Mapplethorpe’s stark, coded photography – a perennial reference. Even his branding was memorably minimal: in two vitrines in the exhibition are objects from his famous late 1990s campaigns, which saw New York cabs emblazoned with ‘Helmut Lang’, no clothes on show. The brand spoke for itself.

But Lang’s minimalism was anything but muted. From lacquered eel skin to sheer, cut-out mesh tops, his mostly monochrome lines were punctuated with flashes of texture and fluorescent colour. Strips of leather became dresses on the body; light-wash jeans bore splashes of white paint; while stingray skirts paired with diaphanous tops, and latex-lace dresses, balanced fetish and fragility. Even bursts of cerulean or citron interrupted his mostly monochrome palette. Though some of these garments are displayed in the exhibition as physical objects, they are largely captured through runway film, ephemera and campaigns.

‘Helmut Lang: Séance de Travail 1986-2005’, exhibition view. Excerpts from the MAK Helmut Lang Archive

Instead, Lang’s conviction that clothing and space are inseparable provides the throughline of the exhibition. Sections of his Paris and New York flagships are recreated as sculptural environments, with sleek black cube dividers by Richard Gluckman sitting alongside Jenny Holzer LED texts (Lang undertook numerous collaborations with artists during his career in fashion; since exiting his label, he is now an artist himself). ‘How do I communicate to visitors how special these stores were? Not just because they sometimes casually housed incredible artworks, including Louise Bourgeois’ metal spider sculptures, but because their architecture made you look a certain way,’ Wirth says, speaking about the exhibition design.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

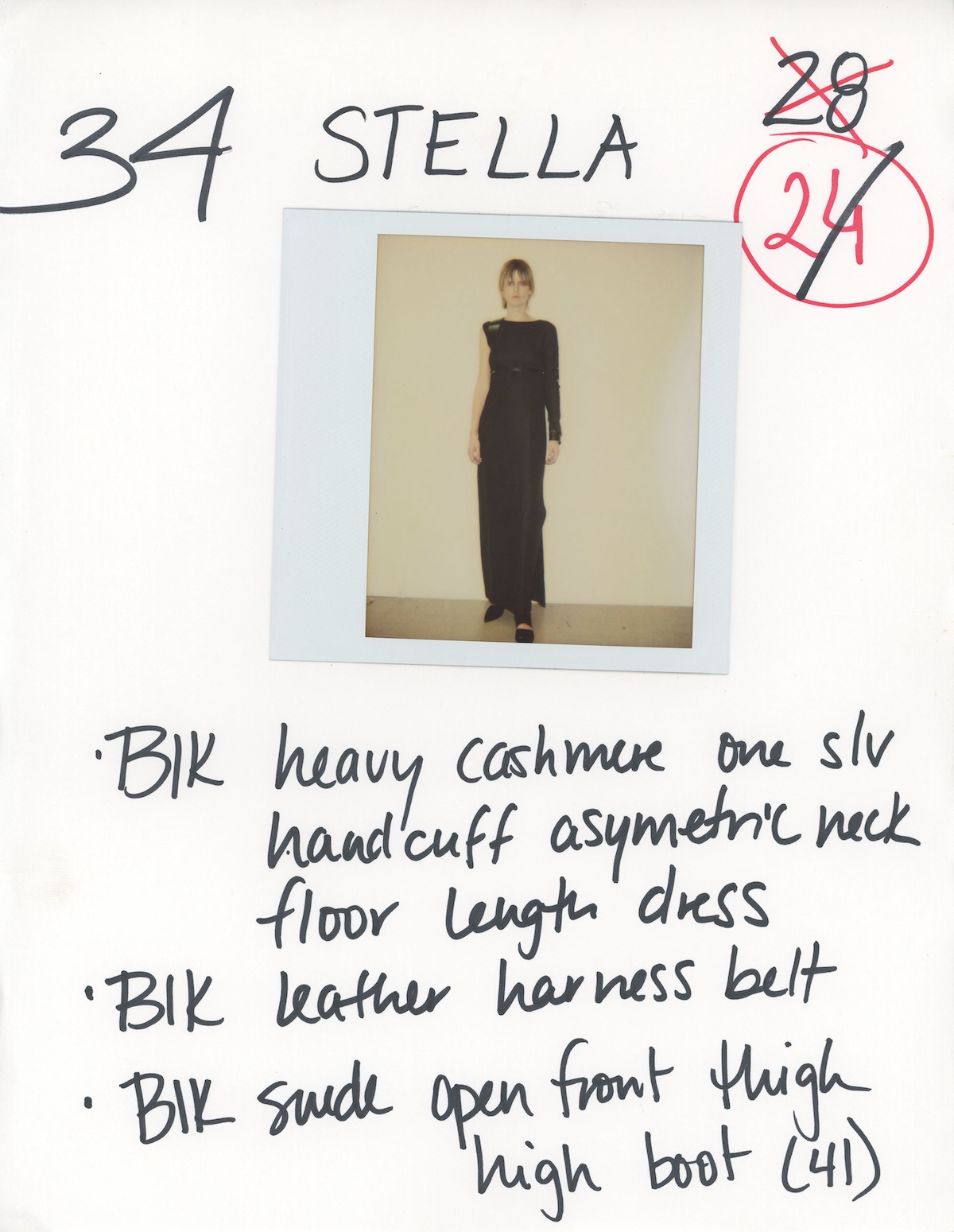

‘It was clear there needed to be a section devoted to backstage,’ she continues. ‘And backstage not only in the literal sense, with footage from the Paris shows, but as a lens on work-in-progress and process.’ Life-size video installations allow visitors to experience the original ‘Séance de Travail’ presentations with their original soundtracks, while lookbooks, Polaroids and fittings also feature. ‘From 1993, his collaboration with Juergen Teller brought new intensity. Immediacy, fragility, and fragmentary perspectives replaced the externally constructed visual aesthetic typical of fashion photography and gave backstage photography increased public visibility.’

‘Helmut Lang: Séance de Travail 1986-2005’, exhibition view. Excerpts from the MAK Helmut Lang Archive

Lang and Teller established a new model of visual communication that not only reshaped the image culture of the 1990s but has become a defining component of contemporary fashion and advertising photography. Fashion commentator Simon Doonan famously observed that Lang ‘casts his shows like a Fassbinder movie’. Cinematic and precise, the runways often mixed Viennese friends, like photographer Elfie Semotan, with models who defined 1990s minimalism: Stella Tennant, Amber Valletta, and even Kate Moss, at the height of her fame, appeared for a look. Among the vitrines displaying Lang’s archive are staff notes, including one from December 2004 that reads: ‘Sent Bill Murray, who seems to be getting quite a bit of press lately, some clothes for the cover of Time magazine. Maybe he has decided to get a publicist.’

Collaborations punctuate the exhibition, underscoring Lang’s interdisciplinary practice. Holzer’s LED and scent installations, his close friendship and work with Bourgeois, and Mapplethorpe’s disciplined lens converge with Lang’s preoccupations of materiality, memory, and surface, creating a networked practice where fashion, art, and architecture intersect. The exhibition’s title, ‘Séance de Travail’, embodies Lang’s philosophy: creation is iterative, continuous, and interconnected.

Helmut Lang, Show Fitting Polaroid on paper with handwritten look descriptions, Helmut Lang Collection Hommes Femmes Séance de Travail Défilé # Hiver 01/02 (2001). Depicted person: Stella Tennant

The exhibition also makes one thing clear: today’s designers rarely enjoy such autonomy. Making certain choices, including to show in New York instead of Paris and structuring a collection around concept rather than commerce, are nearly impossible today. Yet Lang’s precision, tension and spatial intelligence continue to inspire young creators, offering fertile ground for thinking critically about clothes. Even details like his carefully curated soundtracks, including classical music fused with synth-pop and folk, speak to a holistic approach. The exhibition captures a designer who is quiet, precise, uncompromising – a blueprint for creative autonomy, and proof that one person, a small team, and a singular vision can still change the way the world sees fashion.

It feels particularly charged that the first retrospective of Lang’s oeuvre opens not in Paris, London, or New York, but in Vienna, the city where he was raised and where he first began reimagining what clothes could be. MAK holds the only official public archive of his work, a 10,000-piece compendium he donated in 2011. Bringing it into public view now feels like both a revelation and a return. In an era saturated with spectacle, ‘Séance de Travail’ reminds us why Helmut Lang’s radical understatement endures.

‘Helmut Lang: Séance de Travail 1986-2005’, is now open at Vienna’s Museum of Applied Arts (MAK), until 3 May 2025.

‘Helmut Lang: Séance de Travail 1986-2005’, exhibition view. Excerpts from the MAK Helmut Lang Archive

Sofia Hallström is a Sweden-born artist and culture writer who has contributed to publications including Frieze, AnOther and The Face, among others.