How Charlotte Perriand helped shape a progressive modern world through design

Everything you need to know about the French designer who pioneered modular living and tubular steel designs and combined them with humanity and pleasure

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Charlotte Perriand was one of the few women to shape the development of modernist design in the 20th century, breaking ground in an industry dominated by men. Through furniture and interiors, her style adapted the uncompromising geometry of the era to the shape of bodies and realities of everyday life, without losing the bold vision that made modernism truly revolutionary. Though she frequently collaborated with modernist designers Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, Perriand made a lasting mark on the evolution of design all her own.

Charlotte Perriand's life and influences

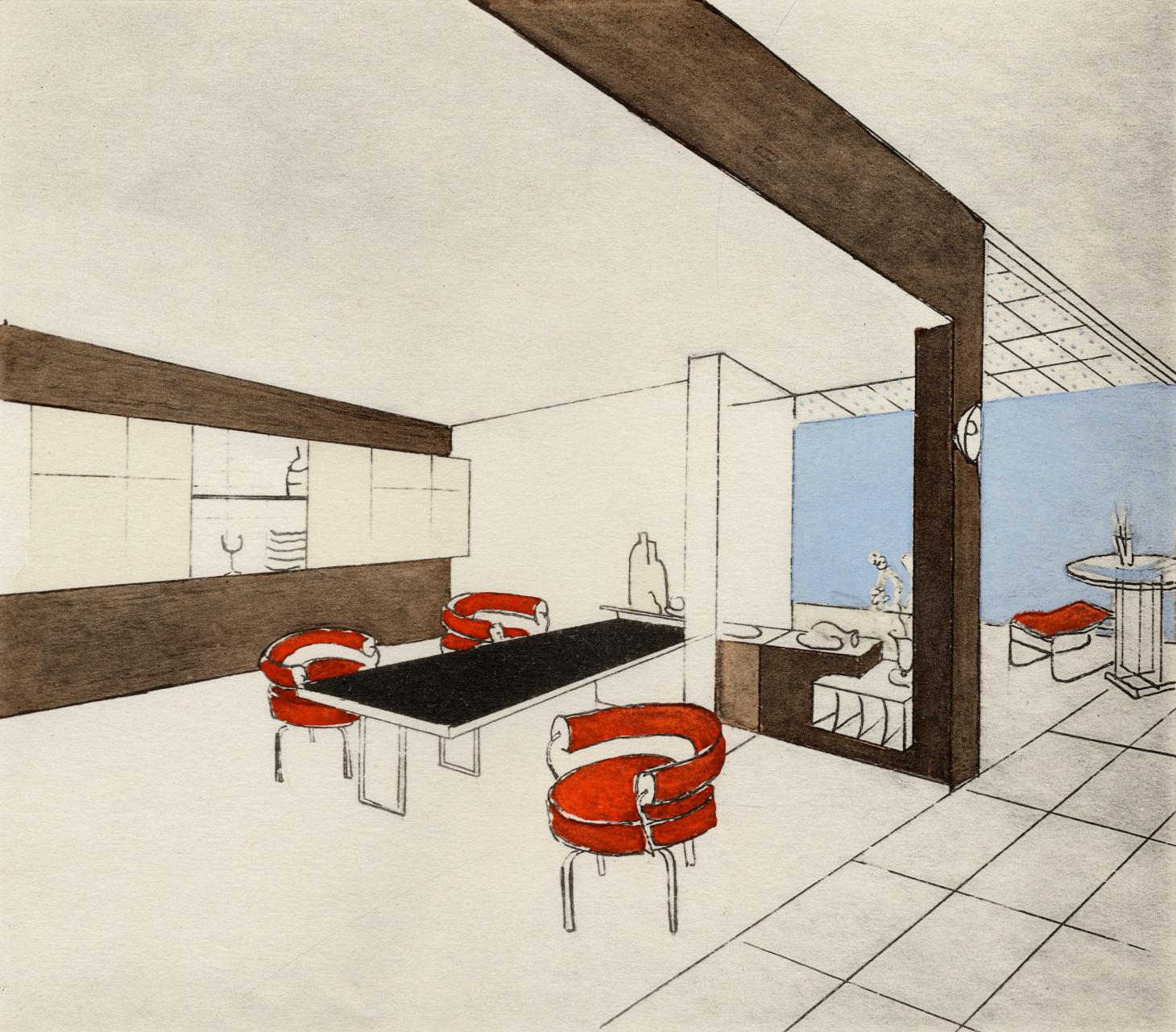

Charlotte Perriand, perspective drawing of the dining room in the Place Saint-Sulpice apartment-studio, Paris, 1928

Born in 1903 in Paris, Perriand studied at the École de l'Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs (1920–1925), before establishing herself as an interior and furniture designer. From her apartment-studio on Place Saint-Sulpice, she developed designs that eschewed decorative detail and drew on new materials including chromed tubular steel – such as her ‘Swivel Armchair’, which combined a metal frame with red leather upholstery.

Place Saint-Sulpice apartment-studio room recreation with the ‘Table extensible’ (Extendable table), 1927 (Centre Pompidou, Paris National Museum of Modern Art – Centre for Industrial Creation), and the ‘Fauteuil pivotants’ (Swivel chairs), 1927 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London). The chairs are now part of Cassina's collections

Filled with her furniture designs, Perriand’s apartment became an expression of her early approach – a vision of sleek metal and minimalist forms. In 1927 she recreated the space in an installation for the Salon d’Automne, an annual exhibition devoted to avant-garde arts. The story goes that Le Corbusier – who turned down Perriand’s request to work together mere weeks beforehand, with the dismissive line ‘we don’t embroider cushions here’ – saw the installation and immediately hired her to join the atelier he ran with his cousin, the architect and furniture designer Pierre Jeanneret.

A tubular steel pioneer

Fauteuil Tournant, 1927, from Cassina iMaestri

Some of Perriand’s best-known work emerged from her collaborations with Le Corbusier and Jeanneret over the subsequent decade. As well as designing interiors for architectural projects including the Villa Savoye and Villa Church, two residences on the outskirts of Paris, she is said to have introduced the pair to tubular steel in furniture design.

The material was central to the creation of three designs – the ‘Adjustable Chaise Longue’, ‘Grand Comfort Armchair’, and ‘Tilting Back Armchair’ – that showed how furniture could adapt to work and leisure. The combination of rigid steel structures with soft canvas or leather resulted in utilitarian designs that were nonetheless luxurious.

'LC4' chaise lounge by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Charlotte Perriand, 1928, om Cassina iMaestri

The chairs were exhibited at the 1929 Salon d’Automne, within an open-plan model apartment. Inspired by the prevalent ‘machine age’, a time of industrial advancement and mechanised production, Le Corbusier had in 1923 written that a house was a ‘machine for living in’ and furniture its necessary equipment. Perriand, though aligning with the era’s ethos of mass-produced egalitarian design, infused Corbusier’s technical approach with humanity and pleasure.

A photograph of Perriand reclining on the chaise longue at the 1929 exhibition has since become iconic, as her relaxed pose alongside her cropped hair and knee-length skirt embodied the progressive modern world Perriand and her contemporaries were building for themselves.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Works in wood

By the mid-1930s, Perriand’s grip on tubular steel was loosening, and she soon embraced natural materials such as straw and wood. She turned away from Le Corbusier in 1937 to pursue her own designs.

Her wooden ‘Free-form’ tables, a series which began in 1938, were simple and practical, while elegantly refined. Designed for everyday life, they took into account varied spaces and ergonomics, often displaying organic contours. Perriand’s biographer (and son-in-law) Jacques Barsac described them as having a ‘poetic functionalism on the human scale’.

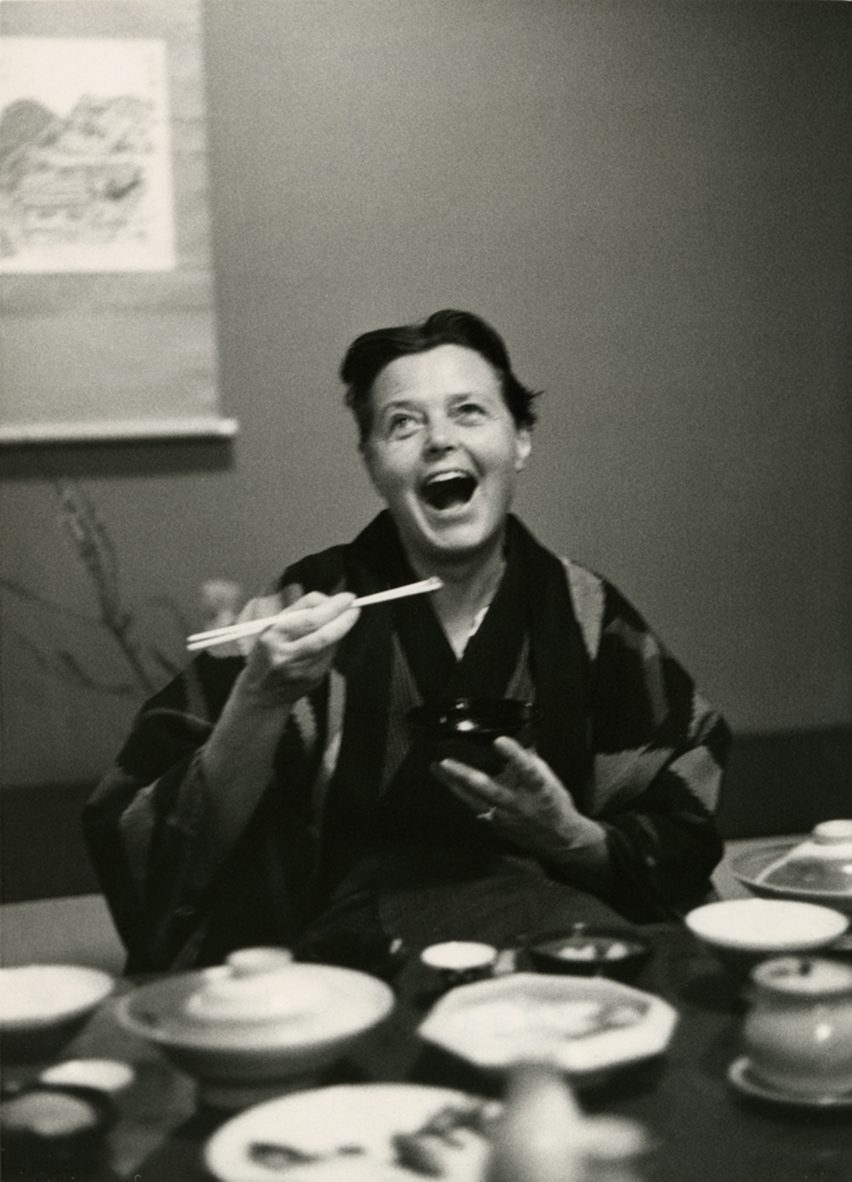

The Japan years

In 1940, just before the Nazis invaded France, Perriand sailed to Japan for two years, where she acted as official advisor on industrial design to the Japanese government. Her 1941 exhibition Tokyo and Kyoto, ‘Selection, Tradition, Creation’, showcased her own modernist designs through the lens of Japanese craft, made with materials such as bamboo and straw.

‘Nuage’ bookcase

Her time in Japan was pivotal on the trajectory of her style, with subsequent work displaying clear influences of Japanese design: rooted in nature – yet efficient and utilitarian.

Perriand’s famous ‘Nuage’ (‘Cloud’) bookcase from 1953 was reportedly inspired by shelves she saw in the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto. Her modular, rectilinear design combines sliding panels, trays and wooden shelves that could be rearranged according to need. Multiple iterations were produced over the years, their rhythmic grid compositions recalling Mondrian paintings come to life.

Modularity and the art of living

Air France offices in Tokyo

For Perriand, modularity was central to achieving flexibility and freedom, and, resuming collaboration with Le Corbusier, she designed a modular kitchen for his 1952 Unite d’Habitation in Marseilles, a now-iconic mass housing block that kickstarted the brutalist style. The compact kitchen had built-in cabinets, easy-to-clean aluminium countertops and multifunctional features. A bar counter with sliding doors for dishes below provided integration with the living areas, enabling the user to be visible and connected to family life.

Perriand believed furnishings, art and architecture should be designed together to achieve the ‘art of living’, and in 1955, on a return to Japan, she demonstrated this approach in the ‘Synthèse des arts’ exhibition in Tokyo. Presented as a complete interior, the exhibition featured her furniture designs alongside artworks by contemporary and friend Fernand Léger.

Perriand applied this approach to the interiors of student accommodation projects in Paris – the Maison du Mexique and Maison de la Tunisie, both 1952 – where she collaborated with artists including Sonia Delaunay on the colour schemes and Ateliers Jean Prouvé on the furniture. Perriand also worked with Prouvé on modular metal and wooden furniture for the Air France office and employee housing in Brazzaville, Congo, in 1952.

Air France was an important client for Perriand – a collaboration strengthened by her husband, Jacques Martin, who worked for the firm – and she remodelled its offices in Paris, London and Tokyo between 1957 and 1963, blending practical business needs with a vision of modernity and comfort. The ‘Nuage’ bookcase became a statement room divider, and the modular approach to fittings and furniture enabled flexible configurations.

Perriand’s vision also extended to whole buildings. Early work focused on pre-fabricated structures: her 1934 design for a wooden waterside house on stilts (Maison au Bord de l'Eau) was intended for mass production (it was only constructed posthumously in 2013 for Louis Vuitton, which has showcased it at fairs and exhibitions since). Refuge Tonneau, a mountain shelter she designed in 1938 with Jeanneret, took the form of a futuristic, spaceship-like metal exterior in dodecahedron form with pinewood interiors; unbuilt at the time, it was later created by Cassina.

'Les Arcs' photographed in 1988

In 1967, however, she led a team of architects and designers to create the Les Arcs ski resort in the French Alps, her largest architectural project. A collection of angular buildings reflecting their mountainous surroundings, the resort hosted hundreds of guest rooms benefitting from generous views and minimalist furnishings.

Perriand died in Paris a few days after her 96th birthday, in 1999, but her legacy and influence endures. A recent resurgence of interest includes a travelling retrospective at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris (2019) and Design Museum in London (2021) and displays of her work at Milan Design Week 2025 presented by Saint Laurent and Louis Vuitton. Major brands including Cassina continue to produce her designs, ensuring Perriand’s vision for modern life can continue in our interiors.

Six Charlotte Perriand designs to know (and own)

One of Perriand’s key works exhibited at the 1927 Salon d’Automne was the ‘Swivel Armchair’, a practical yet playful design combining tubular steel and leather. Also known as the ‘LC7’or ‘B302’, it embodied a punchy modern aesthetic recalling the work of Marcel Breuer, but with more liveliness and sumptousness. It was manufactured in the early 1930s by Thonet, and an evolved version with various finishes is now produced by Cassina.

Designed with Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, this was presented to the public at the 1929 Salon d’Automne. Featuring a leather recliner held by a sweeping arc frame of tubular steel, the chair blended machine-age technical precision with sensuous elegance. Also known as ‘LC4’ or ‘B306’, the design has since become an iconic modernist design. Initially manufactured by Thonet, the chair has been produced by Cassina since 1965.

Perriand’s lighting designs often displayed the adaptability she prioritised in her interiors and furniture. The ‘Pivotante a Poser’ lamp took on a compact, playful yet practical form, its cylindrical metal exterior rotating to enable the direction and intensity of the light within to be controlled. This is one of multiple Perriand lighting designs produced by Nemo.

Although Perriand began to design this series in 1938, embracing natural wood and organic contours, the tables only went into production in 1959 thanks to Galerie Steph Simon. Designed in various sizes and at different heights, the tables had three legs and asymmetric forms to elegantly adapt to space and bodies.

After visiting the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto, Perriand wrote in her journal about seeing shelves ‘arranged in the form of a cloud’, a formation she admired for the way it ‘gives rhythm to space and enhances the objects it supports’. It is believed that Nuage developed from this idea, with a design that could adapt to different contents and locations. Perriand used the design in many of her interiors, sometimes doubling as a room divider. The early versions are entirely in wood, while later ones also employ aluminium.

This stackable, lightweight chair was made from a single piece of plywood – cut, folded and curved, evoking the paper art of origami – and manufactured for Tendo. Unveiled at the ‘Synthèse des arts’ exhibition in 1955, it shows the influence Japanese design had on Perriand’s work. It is now produced by Cassina.

Francesca Perry is a London-based writer and editor covering design and culture. She has written for the Financial Times, CNN, The New York Times and Wired. She is the former editor of ICON magazine and a former editor at The Guardian.