Super sense: Sissel Tolaas gives us an education in smell

With a new project that explores togetherness through smell, Berlin artist Sissel Tolaas is leading us by the nose

Adrian Escu - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Sissel Tolaas sniffs where others fear to tread. ‘When other people start throwing up,’ she says, ‘that’s when I start to work.’ The self-professed scientist of smell has created cheese from David Beckham’s sweat and finds the odour of ordure far more fascinating than what she calls ‘cover-up perfumes’. But she has also recreated the scent of extinct flowers and encapsulated the life story of a Douglas fir tree in a Dinesen plank.

Though she’s long been based in Berlin, Tolaas was born on the west coast of Norway, where, she recalls, ‘we always looked west, to America’. The young Tolaas, by contrast, looked east. At 17 she left squeaky-clean Scandinavia, first for Poland and then for Russia, to study organic chemistry and linguistics. ‘I need to be somewhere I feel uncomfortable,’ she says, ‘so I had to get away from the safety of home.’ For this, she couldn’t have chosen a better time and place; she arrived just as the old Soviet Union was coming apart at the seams. ‘Everything in Russia was so political,’ she recalls. ‘Even in church, the priests would be preaching politics, not religion.’

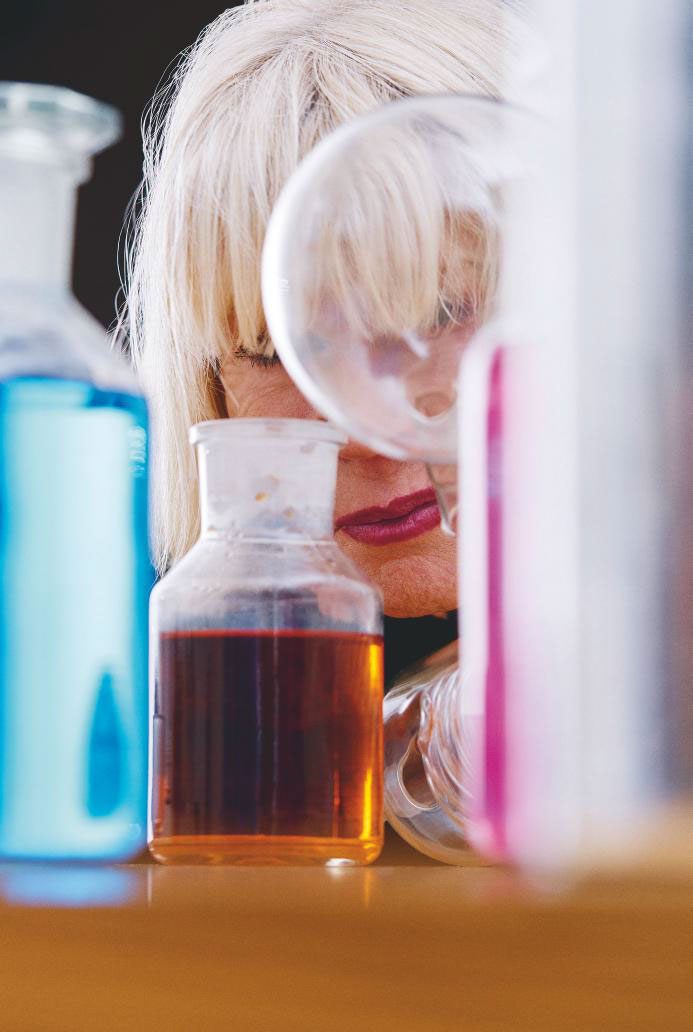

Sissel Tolaas in her Berlin laboratory, where her research into smell spans science and art

It was partly to get away from the supercharged politics of the day that she started thinking about non-verbal communication, and that led, eventually, to her obsession with smell. Tolaas does mean smell, not perfume. Her view is that we now experience far too much via sight and sound, and that we’ve lost an essential component of our humanity as a result. ‘We breathe 24,000 times a day,’ she says. ‘Every breath tells us something about the world, yet we have, essentially, forgotten how to smell.’ Not only that, but over the last century a vast industry has grown to sell products that actively suppress what we’ve been taught to think of as dirty smells. The result is what Tolaas calls ‘blandscapes’ – sanitised cities, their natural odours scrubbed and sprayed to extinction.

It may seem ironic that, since 2004, her work has been supported by International Flavors & Fragrances (IFF), one of the biggest global players in ‘cover-up perfumes', whose perfumers have had a hand in everything from high-end fragrances for Frédéric Malle to the stuff you squirt down your sink. Yet the hook-up makes sense, since in the end, Tolaas and IFF are interested in the same things. ‘When I first met their CEO I’d already been researching smell for years,’ Tolaas says, ‘but my research was completely hermetic: I knew nothing about the fragrance industry. Luckily, they saw the potential of my work, and that changed my life. Their support enabled me to set up my research studio in Berlin, and it’s been fantastic to have access to their R&D.’

Her research has taken her all over the world, and involved intriguing collaborations. Her ‘celebrity cheese’ project with synthetic biologist Christina Agapakis investigated the differences between ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ smells. Based on the premise that the bacteria that turn milk into cheese are similar to those that live on our skin, Tolaas used sweat from David Beckham’s Adidas trainers to make cheese, which was served to VIPs at the London Olympics.

More recently, she was commissioned by Balenciaga to create the smells of blood, antiseptic, petrol and money for its S/S20 show, and by Dinesen to help tell the story of its products through scent. She collected samples from Douglas fir trees in the Black Forest, as well as from the Dinesen sawmill at Jels in Denmark, including the workers. From this archive she developed a scent, DD-2, launched at the 2019 London Design Festival and shortlisted for a 2020 Wallpaper* Design Award. ‘It got people talking about people rather than just about planks,’ she says.

Seaweed awaiting analysis in Tolaas' lab

For her latest collaboration, at London’s Science Gallery, she’s worked with audiovisual artist Jenna Sutela and New York-based writer Elvia Wilk on an installation entitled nnother, part of the exhibition, ‘Genders: Shaping and Breaking the Binary’ (until 28 June). The project, a take on the mother-child relationship, explores the effects of the hormone oxytocin, and includes a scent embedded in the walls, intended to give visitors a feeling of togetherness.

Bringing people together is what Tolaas’ work is all about, and bringing us back to our senses. ‘People don’t use their noses, because marketing took over and science stood back,’ she says. ‘Relearning to smell is difficult, you have to work hard at it, but the moment I learned what the nose can do it gave me great joy and freedom.’

INFORMATION

As originally featured in the April 2020 issue of Wallpaper*, available to download for free here.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.