Man at work: rigour, neurochemicals and 24/7 assistants at Takashi Murakami’s studio

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

So far, 2017 has been a busy year for Takashi Murakami. His first solo show in Scandinavia, ‘Murakami by Murakami’, ran from February to May at Oslo’s Astrup Fearnley Museet, and was closely followed by ‘The Octopus Eats Its Own Leg’, an exhibition of his paintings at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, on show until 24 September. Just five days later, the artist’s first major survey in Russia opens at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow. Murakami likes it this way. ‘I am very grateful that my exhibitions are held simultaneously around the world,’ he says. ‘In the midst of this boom of a sort, I feel my head is spinning, though I feel anxious when I think about a quiet future without such flurries of activity.’

Murakami really lives for his art. He literally camps down in his factory-sized studio in Miyoshi, a rather bleak, predominantly industrial area about an hour outside Tokyo. He sleeps there, in a large cardboard box in a corner of one of the rooms. He eats there, often preparing his own simple meals. And, of course, he works there. The studio is in operation 24 hours a day, seven days a week. In the early evening, the night shift takes over from the day shift, and the hectic working schedule runs on.

The studio is remarkably clean and highly organised. Large sheets of cardboard give information about who is on duty, production schedules and deadlines, and changes to artworks. When a dot of black paint has been added to a painting, the painting is photographed. This photograph is then printed out, time-stamped and added to the production board for the artwork so Murakami can go back to previous versions if he chooses. He is constantly making changes and doesn’t like deadlines for wrapping up his art. ‘The deadline of an exhibition used to be my deadline,’ he says. ‘Today, if I am really unhappy about a particular work, I will ask for it to be returned to the studio after the exhibition so I can complete it. If I keep at it for more than two years, however, the galleries and the clients start to become seriously upset, so when their anger reaches tipping point, I deliver the work.’

On sheets of cardboard, a record of the many changes each artwork goes through.

In lieu of windows, the studio is illuminated by hundreds of fluorescent tubes, making it impossible to tell the time of day. There is also hardly any sound. Staff work assiduously at computers or crouched over paintings. Murakami sits at his table, sketching or making corrections on transparent sheets of vinyl superimposed over printouts of works in progress. From time to time he walks around, with his dog Pom in tow, to check on what’s happening and give orders to assistants. ‘I live like a monk, which is a way to induce the release of neurochemicals in my brain to heighten the senses and achieve a state of alertness,’ Murakami says of his rigid working style. When Wallpaper* visited, his focus was on the exhibition at Garage. The opening was barely two months away and several of the commissioned works for the show were still unfinished.

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art was founded in 2008 by oligarch Roman Abramovich, an avid art collector, and his then wife Dasha Zhukova. The museum takes its name from the bus garage, designed by constructivist architect Konstantin Melnikov, that was its first home. After a brief period in a temporary space designed by Shigeru Ban, the museum moved in 2015 to a permanent location, a prefabricated concrete pavilion that previously housed a restaurant. The space had been out of use for more than two decades and was in ruins when Zhukova commissioned an overhaul by OMA, which wrapped the existing concrete structure in a double polycarbonate skin. The wide, open spaces were renovated but kept as close to their original form as possible. A beautiful mosaic mural depicting autumn, which now greets visitors entering the museum, was also salvaged from the restaurant.

For the past two years, Garage’s senior curator Katya Inozemtseva has been hard at work on the exhibition. To explain Murakami to a Russian audience, she has organised more than 70 artworks into five sections, each exploring a Japanese cultural phenomenon that is examined in Murakami’s art. In the ‘Kawaii’ section, a new 3m long painting serves as a backdrop. Featuring Murakami’s trademark smiling flowers, the partly gilded piece introduces visitors to the artist’s treatment of the Japanese concept of ‘cuteness’, via an all-star cast of Doraemon, Pokémon and Hello Kitty characters.

The ‘Geijutsu’ section promises to appeal to visitors interested in Murakami’s background in traditional nihonga painting. Situating his art in a historical context, it also features older works by Katsushika Hokusai, Kawanabe Kyosai and Utagawa Kuniyoshi, on loan from the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, to help viewers better understand the references to Japanese art history often found in Murakami’s work. ‘Because the Russian public only has an approximate notion of Japanese history and history of art in particular, we don’t recognise the influences and references he continuously makes,’ says Inozemtseva. ‘Murakami basically continues what has been called the “lineage of eccentrics” that began in the Edo period [1615-1868] with artists like Iwasa Matabei, Kano Sansetsu, Ito Jakuchu and Soga Shohaku. There has never been a show that explores these kinds of connections to history, which is why I wanted to take this approach.’

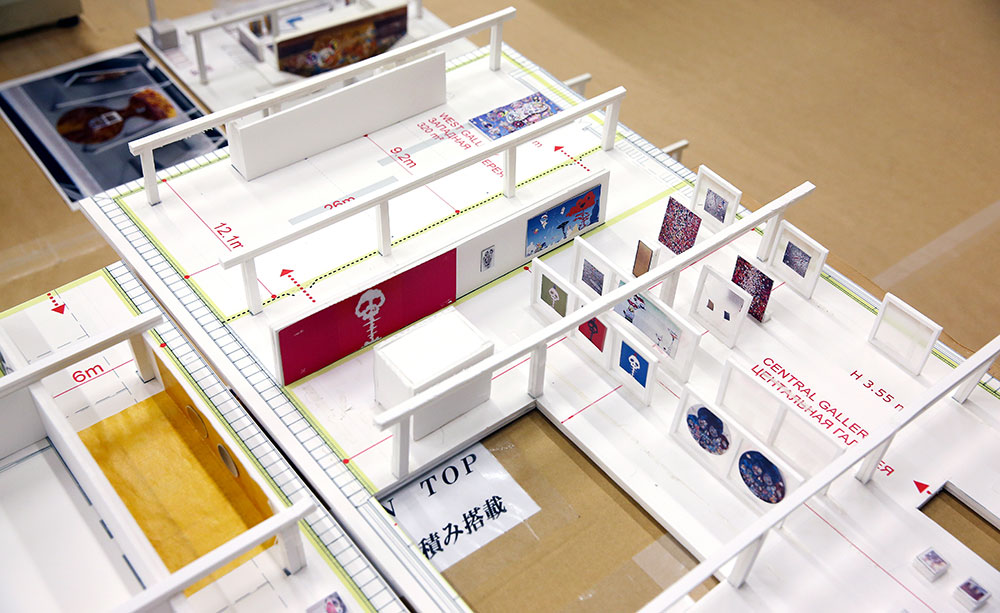

A work in progress model of the Garage exhibition. Specially designed mesh mounts will allow some works to be seen from both sides.

Another section, ‘The Little Boy and the Fat Man’, explores how the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings in 1945 transformed Japanese visual aesthetics. In a European first, Murakami’s Sea Breeze installation from 1992 is on display. The piece is a large, open box on wheels, with a set of mercury lamps in the middle. The lamps turn on and off in powerful glares reminiscent of the flashes after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. According to Inozemtseva, ‘this is the crucial and very early piece that reveals and outlines the shape of Murakami’s intense interest for the whole post-bombing/post-war thematic’. One of the artist’s trademarks also features prominently: a skull appearing out of a large mushroom cloud, which he calls ‘Time Bokan’ after a famous Japanese anime TV series. These motifs engage in a visual conversation with the large neon Time Bokans that decorate the façade of the museum.

Rather than simply hanging the artworks on its walls, Garage is mounting many of them throughout the space on a specially made metal mesh. Inozemtseva wanted to make the back of Murakami’s paintings visible. ‘The back sides are perfect, no less elaborate than the front,’ she says. ‘Plus, you can see the names of all the contributors who participated in the creation of each painting. Sometimes Murakami works on one painting for years, so the list can be almost endless. I believe it reveals his attitude to his team. They are not just anonymous assistants, like in a medieval studio or contemporary art factory. They are highly devoted and appreciated collaborators.’

To offer an insight into the workings of the artist’s studio, Garage is recreating its mood and structure in the ‘Sutajio’ section (a phonetic rendering of the Japanese for ‘studio’). This is another first for a Murakami exhibition: assistants are staying on after the installation to give classes on his art and techniques. The final section, ‘Asobi & Kazari’ (fun and decoration), spreads playful pieces throughout the museum, extending Murakami’s universe to the gift shop, the façade and the world beyond.

As originally featured in the October 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*223)

Murakami’s many assistants work in near silence at the studio, which is operated 24/7, in shifts. On the wall hangs work in progress of a piece comissioned for the Garage exhibition

Left, Murakami sketches and makes corrections on transparent vinyl sheets laid over printouts of his works in progress. Right, the studio’s impressive cactus garden inspires some of the forms in Murakami’s artworks

Murakami’s Vans dry off outside the studio

INFORMATION

‘Takashi Murakami: Under the Radiation Falls’ is on view from 29 September until 4 February 2018. For more information, visit the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art website

ADDRESS

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Moscow 119049

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Originally from Denmark, Jens H. Jensen has been calling Japan his home for almost two decades. Since 2014 he has worked with Wallpaper* as the Japan Editor. His main interests are architecture, crafts and design. Besides writing and editing, he consults numerous business in Japan and beyond and designs and build retail, residential and moving (read: vans) interiors.