Reality check: Sarah Sze brings AR to Fondation Cartier

American artist Sarah Sze explores the shadowy spaces between physical and digital worlds with a new show in dialogue with Jean Nouvel's iconic glass building

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

For a while, early on, the American artist Sarah Sze didn’t say much in interviews. She wanted the interviewer to do a lot of the work. Now she talks a lot. And her conversations, like her work, are expansive, dizzying, serious but sometimes funny, fractured but propulsive, and explosive with ideas. They do focus, if you nudge them that way, on the experience of art and how art is about the way we experience everything. She talks about, and makes art about, the internal and external machinery of experience.

Sze studied architecture and painting, but she is known for large-scale sculptural installations – a logical confluence – mostly built using found objects and scraps of paper, sometimes potted plants and moss. The installations mostly spread beyond their assigned space, precisely strewn, constellations to explore, as much nothing as something. Sometimes they look like exploded workstations in a dust cloud of information, notions and conjecture.

Increasingly, Sze has introduced (or rather reintroduced) moving image into her work, projections on walls and those paper scraps, often of nature at its more emphatic – geysers in full gush, cheetahs in full flight. Roaringly physical elements are presented as fragments, flattened and faded. And Sze’s work more and more addresses the indistinct edges of the digital and physical, our willing offloading of remembering, our immersion in the second-hand. In her new show, ‘Night into Day’, at the Fondation Cartier in Paris – not conceived during the pandemic but impacted by it and spookily prescient and pertinent – she takes this conversation further, adding new engines of experience.

Portrait of Sarah Sze, photographed in August via Zoom, at her Manhattan studio.

Part of her ongoing Timekeeper series, the physical centrepiece of the show is Twice Twilight, a sphere, or the suggestion of a sphere – outlined in torn paper and photographs, potent debris and projected images – held in place by a scaffolding of bamboo and metal rods. As Sze says, there is no sphere there at all, we construct the sphere in our heads. ‘It harnesses space, nesting a void,’ she says.

Again, there are moving images of nature and the elemental. And the installation suggests a planetarium, something cosmological in ambition. Though as the French philosopher and sociologist Bruno Latour says, the implied scale of Sze’s work is often hard to gauge. Is she conjuring up expanding universes or imploding stars, or drilling into the sub-atomic?

A second work, Tracing Fallen Sky, is a mirrored concave bowl made of steel and glazed clay, reflecting, distorting, fragmenting, splintering Sze’s universe of matter and moving image. Above it swings a pendulum, keeping some kind of time, though nothing you could dance to.

The two works fill Fondation Cartier’s Jean Nouvel-designed building and take advantage of its transparency. It is a building she knows well and knows how to work with. The Fondation Cartier presented one of Sze’s first major solo shows back in 1999. It was dominated by a giant single installation, Everything that Rises Must Converge (after a Flannery O’Connor short story), a stopped tornado of 39 disassembled aluminium ladders and a multitude of objects. (Sze says she was somewhat spoiled by the early attentions of the foundation. ‘They just do things extremely well. I was a very young artist when I did that show and it was my first catalogue. And they are in an industry where everything has to be excellent so the printing was amazing, everything was colour corrected perfectly, the writing was beautiful. It was just exquisite. The second show I did was at an academic institution and when I got the catalogue, I was horrified. I couldn’t wait for it to go out of print.’)

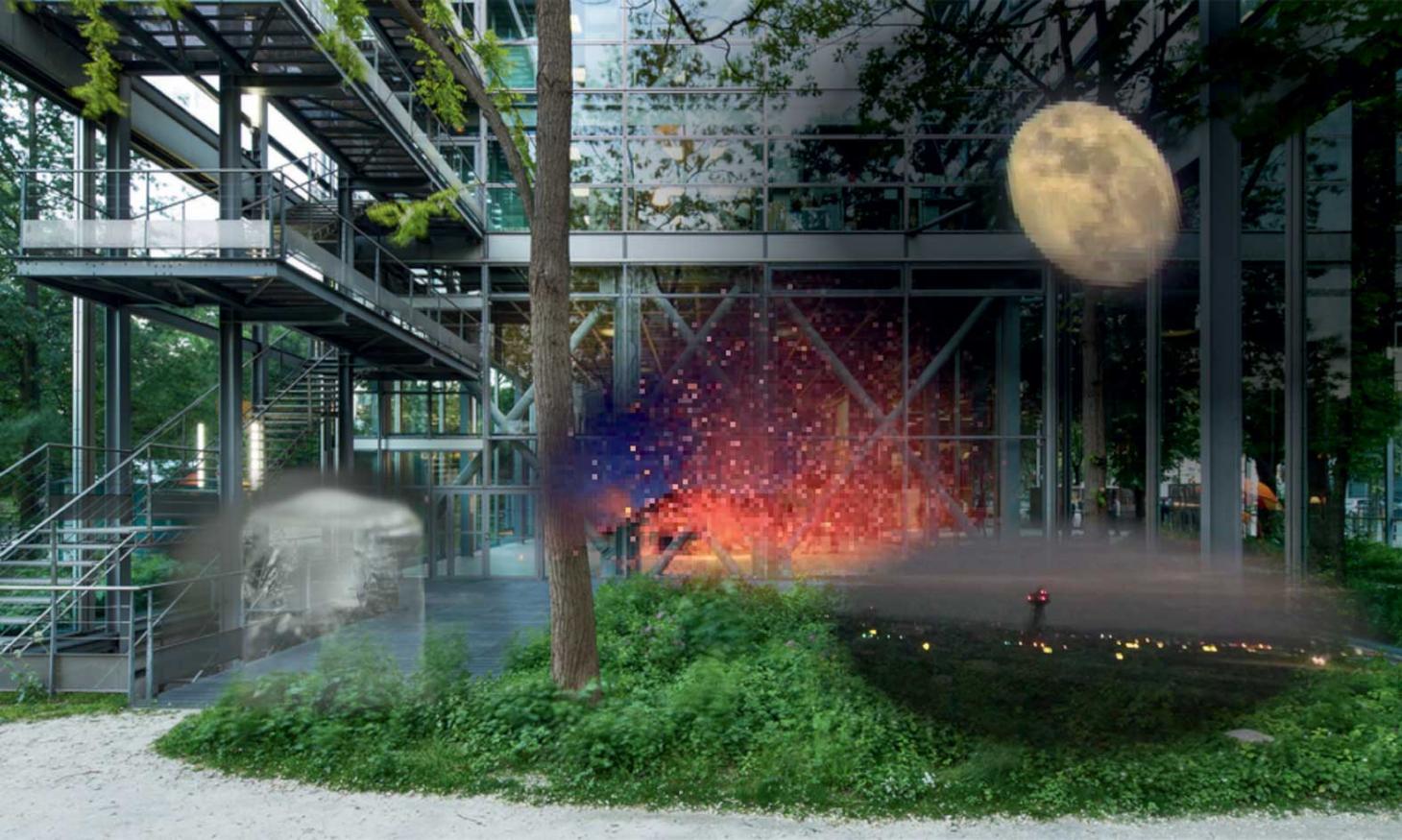

A render showing how smartphone-enabled daytime visitors to Fondation Cartier might see how the exhibition looks at night with the use of augmented reality technology. AR project renderings: 2020, Sarah Sze Studio

Much of Sze’s work is site-specific, sometimes even conceived and created on site. ‘With the Cartier show, I had actually conceived and done one whole piece before the pandemic. So the second one would have been much more improvisational and created on site, but I’m doing it improvisationally from the studio in New York, directing someone in Paris.’ And Sze is getting used to working remotely, off-site but on-site. ‘We’ve done six shows or major pieces since the beginning of the pandemic and we’ve figured out how to do things pretty successfully, but it needs really amazing people on the ground.’

For an installation artist, and certainly one as alert to the particular topographies of her work, and to the creation of energy and accident, this is no small deal. ‘I wanted to make work that felt like it was totally made in the moment, in that gallery, not in the studio. I’ve tried to preserve some of those very fragile moments of discovery that make you feel like you’re in a live space.’

These new creative mechanics reflect some of the concerns of Sze’s work, that digital/physical divide, ‘what needs to be done physically, what can we do digitally and what is that dystopic place between the two. And how that affects the way we remember things. The way we imagine things.’ (Sze did, she admits, enjoy the degree of control our Zoom photo shoot allowed. ‘Because it’s very invasive when a photographer comes into the studio. You have no idea what they want and they’re capturing your space, your artwork. And that can go well or it can go very badly. But this way, I have the screen, you can see yourself and it becomes a complete collaboration.’)

RELATED STORY

A key motivation to return to the Fondation Cartier was the building itself. Completed in 1994, Nouvel’s gallery is a giant glass box with a wildflower garden fronted by another huge glass wall. It is an emphatic but barely-there building, playing with ideas of inside and out, layers of reflection and transparency, de- and re-materialising according to the weather, light, time.

The Fondation Cartier in Paris, an airy glass and steel structure designed by Jean Nouvel in 1994, will host an immersive installation by Sze that will transforms the visitor’s perception and experience of the building.

Few galleries offer as many conversational angles as Nouvel’s. ‘I’ve always loved this building,’ says Sze. ‘I think it’s a masterpiece. When I installed there in 1999, I spent like a month in it, so I really know it. It has a very strong language and you have to engage with that language so it becomes a conversation. In my first show I wanted to turn up the play in the building, to show that it is playing with us. This time I’m using the building as a machine, an image maker, co-opting the building as almost like a camera itself.’

For Sze, for all of us, the screen (phone, iPad, laptop, TV) is a portal, a point of departure into peril and possibility. Nouvel’s building allowed her to supersize that idea. ‘One of the strangest, most radical things about the building is that it is a massive glass screen, a screen that you are kind of passing through. It’s a gateway and then the interior and exterior are constantly flipping.’

As the show’s title suggests, Sze is taking advantage of autumn’s earlier nights. As darkness falls, ‘the entire building will become like a mirage of spinning images, a large zoetrope’. Clearly, during the day this effect will be less impressive. Which is where augmented reality (AR) comes in.

Those looking to advertise the creative potential of AR and VR have long courted Sze. Her work, super-smart, a bit sciency and crucially multi-dimensional, porous and walkable through, seemed like the perfect base material of some kind of AR treatment. Sze wasn’t seeing it. The technology – at least the applications of it that had been suggested to her – was a ‘hammer without a nail’, a tool with nothing to offer.

An installation prototype in Sze’s studio, 2019.

Here, though, there was something AR was good for: it could offer smartphone-enabled daytime garden visitors the chance to see the building at night, to overlay the nighttime display onto day. The phone could become a sort of time machine, zooming you half a day forwards or backwards.

Sze had also been fascinated by the Pokémon Go phenomenon and how that AR treasure hunt became a kind of global mass choreography. She noted how willing people were to become part of that choreography, to happily wander into and linger in that liminal space. Here she could do something similar, choreograph her own kind of dance in the garden. ‘It was a way of activating the outside space,’ she says. ‘And you’re in nature but having this human-made experience. It was the first time I thought there is a need for AR here, to expand the experience of space, rather than let’s think up an AR project. So this isn’t an AR show, it’s a show with a piece where the digital goes into nature and makes you weirdly more aware of your body and that nature. Hopefully it will work and in ways that I don’t understand.’

There is another fascination for Sze in this digital/physical between place; that it might, in some ways, approximate our interior world. ‘Scale is totally screwed up on a screen because scale only relates to the human body. And so trying to create something that surrounds you on a screen is such an interesting idea. And it mirrors the space of the interior world more than the space of the physical world. When we dream, there is no real sense of scale. And we spend so much time with the images that are in our head, but we discuss this as a physical space far less than we should.’ That’s where Sze’s art lives, on the borders between our interior and exterior worlds, and physical and digital worlds. It talks about what passes between, experience, memory, what sense-making machines and engines we build. ‘If you are a visual artist and you are trying to depict something from the real world, you are constantly humbled by the complexity of seeing or perceiving something, remembering something or recalling or imagining it.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

This article originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of Wallpaper* (W*259) – on newsstands now and available for free download here

INFORMATION

Sarah Sze, ‘Night into Day’, 24 October – 7 March, Fondation Cartier. fondationcartier.com; sarahsze.com

ADDRESS

261 Boulevard Raspail

75014 Paris