Sarah Morris cuts through the noise at White Cube

It’s a homecoming of sorts for the Kent-born, New York-based artist, who debuts new paintings and her first ever sculptural work at the gallery’s Bermondsey space

Sarah Morris is having a moment: the US artist’s first solo exhibition in the UK in six years sees her emerge from what has largely been a cocoon of film and painting, along with her first ever sculptural work. ‘Machines do not make us into Machines’ at White Cube Bermondsey is as much an exhibition as a manifesto. But what does it say? A great deal as it happens, though it’s hard to tell rhetoric from reality. Morris believes that truth lies not in what can be proven, but what can be disproved. This London show is what happens when the assertion of a scientist, the insight of political philosopher and the artistic flair of a true radical collide.

Morris was born in Kent to a family of medics and forms Cambridge University’s prestigious alumni. But even before Sarah Lucas, Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst had begun scandalising the nation with sex, death and pickled farm animals, Morris had fled the nest to America. The YBA who got away? Not really, she herself will explain how she might have been born in Britain, but she was made in New York. She now occupies a Long Island studio in a former aviation manufacturing facility – an industrial space for an industrial scale mentality.

For Morris, language is, quite literally, a construct. She’s invented her own painted dialect which looks and sounds somewhere between the synthetic snarl of scrolling computer code and a political declaration. The gathering of ideas is as regimented as the execution, and it all begins with plucking phonetics from sentences and plotting coordinates.

‘Machines do not make us into Machines’ at White Cube Bermondsey.

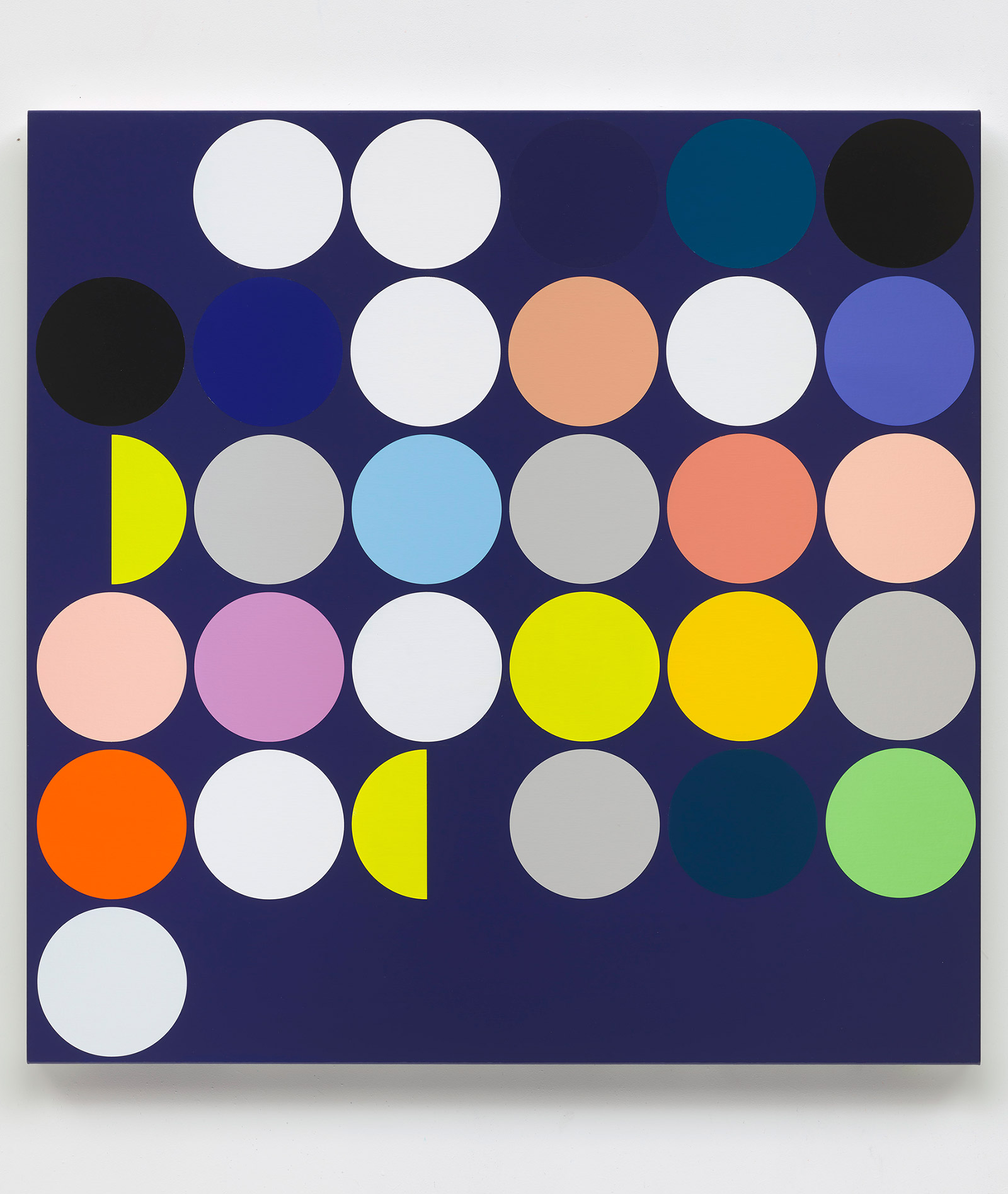

In this painting-rich show, each canvas forms an index for transport networks, surveillance, wild conspiracy theories and global connections. Aggressivity and Thinking (Sound Graph) 2019, demonstrates how sound bites become garishly coloured bars and dots, resembling radio waves and flirting with the language of American abstraction, minimalism and pop art. ‘They’re static but the eye makes them move,’ Morris explains.

Her paintings are as energetic as an Elsworth Kelly and as smooth as the polished concrete floors they watch over. An enormous, site-specific wall painting – named after Ataraxia, a philosophical concept meaning an ‘end state of imperturbable calm’ – is supposed to leave you in ‘suspended judgement’, but you’re too mesmerised to care. Not a smear, drip or speck of dust in sight, just block fragments filled so perfectly to each brim that there isn’t much left for the paint to do. It has the intricacy of a computer motherboard – everything in its right place or it will cease to function.

Morris’ zinger of a sculpture, What can be explained can also be predicted (2019), is a network of vibrant glass tubes which look like one of her paintings has climbed off the walls, sprouted two-metre legs and planted itself on gridded marble plinth. The test tube-like form could be a neon sea anemone, a Vegas chapel organ or something phallic if you squint hard enough. ‘I wanted to make a cross between a musical instrument and an image of a future city, and it has a bit of The Wizard of Oz in it too’ she says.

Compared with the paintings, her films move at a glacial pace. They’re sullen, reflective and pose all the important questions with little resolution. ‘You can project a lot into these narratives that are fragmented, interrupted, don't have a beginning and don’t have an end’ she explains ‘the coordinates are set, the time is set, the but what’s in that moment is not set – that’s the fun part for me.’

Still from Abu Dhabi, 2017, Sarah Morris.

Still from Abu Dhabi, 2017, Sarah Morris.

It seems like Morris has a taste for critiquing capitalism, bureaucracy and power, but that might be a misdiagnosis. They could actually be muses, or she could be totally indifferent. In 2017 architects Herzog & de Meuron hit headlines with a renovation that cost a ludicrous €789 million. Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie concert hall takes the spotlight for Finite and Infinite Games (2017), a film Morris shot within the gleaming, cacophonous belly of its central auditorium, inspired by a book by religious scholar James P Carse.

‘The film became so much more than the script and so much more than this irreparable excuse of the concert hall’ she says, ‘all of that aspiration of the city and all of this capital going into the building.’ This piece is both lulling and disconcerting with no tangible narrative aside from flecks of gaming psychology and industrial capitalism. It all feels in flux, in anticipation of a finale that never comes to be. In a similar vein, Abu Dhabi (2017), a Guggenheim commission, surveys the psycho-geography and political undercurrents of the Middle Eastern capital through film, underlining the consequences of rapid urban transformation in a city that went from desert to decadence in less than half a century.

Much of Morris’ work doesn't look like human hands created it. Her aptitude for order and dominion over paint is intimidating. You leave with her grids, graphs and algorithms still stained on your brain, confused by what you may or may not have seen or learnt, which might be an entirely new language. ‘It all goes back to speech and how you pin meaning to something,’ she says. ‘Art in the end is a series of conversations.’

April 2019, 2019, by Sarah Morris, household gloss on canvas.

Installation view of Sarah Morris’ ‘Machines do not make us into Machines’ at White Cube Bermondsey.

![Machines do not make us into machines [Sound Graph], 2018, by Sarah Morris](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/tc8NiZZcB9bCERgyAxM9w9.jpg)

Machines do not make us into machines [Sound Graph], 2018, by Sarah Morris, household gloss on canvas.

INFORMATION

‘Machines do not make us into Machines’ is on view until 30 June. For more information, visit the White Cube website

ADDRESS

White Cube

144-152 Bermondsey Street

London SE1 3TQ

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.