Alick Phiri’s black and white portraits capture the realities of post-colonial Zambia

After decades of capturing Zambia’s capital city, the photographer returns for an exhibition featuring his works alongside South Africa’s William Matlala

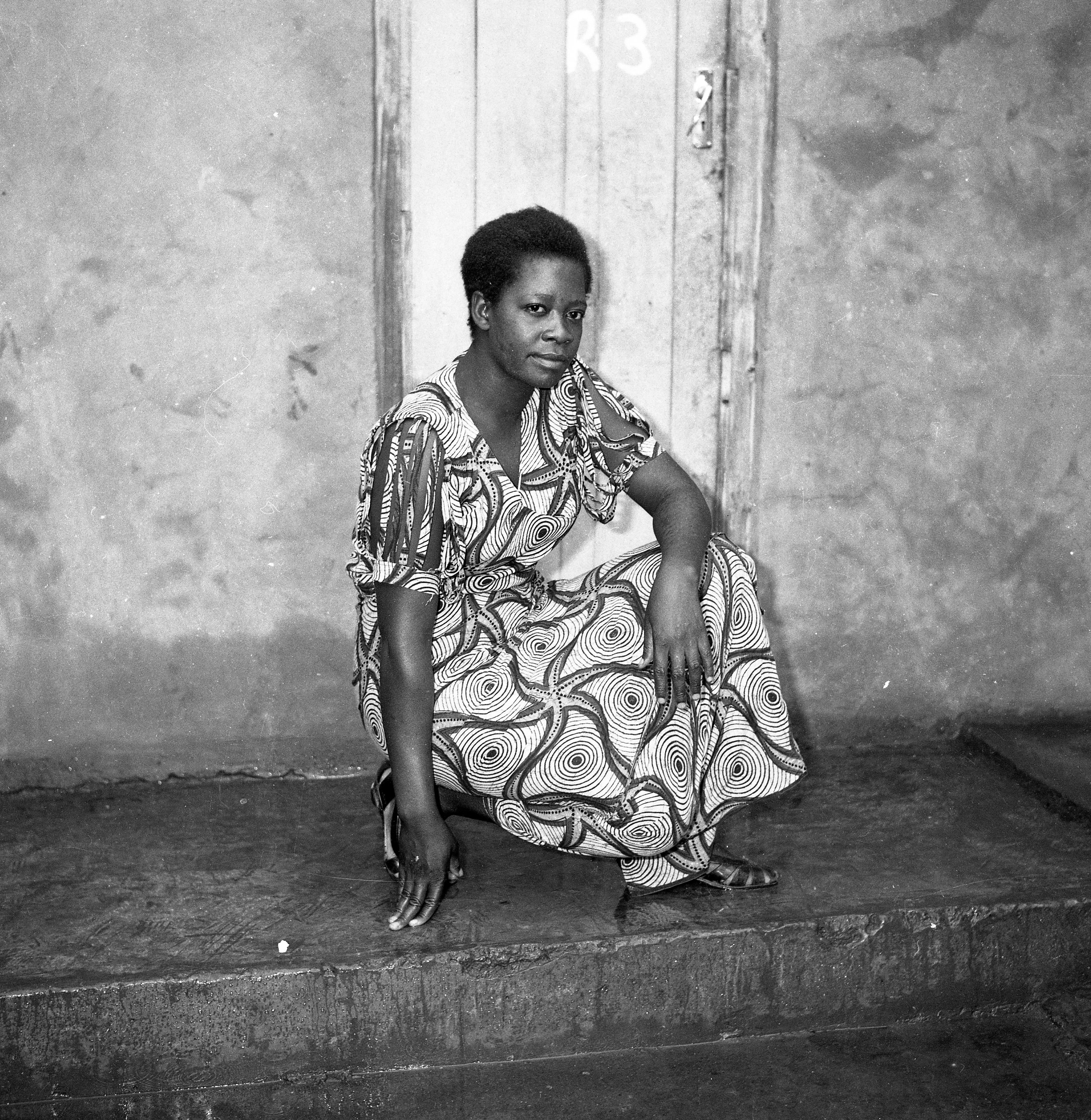

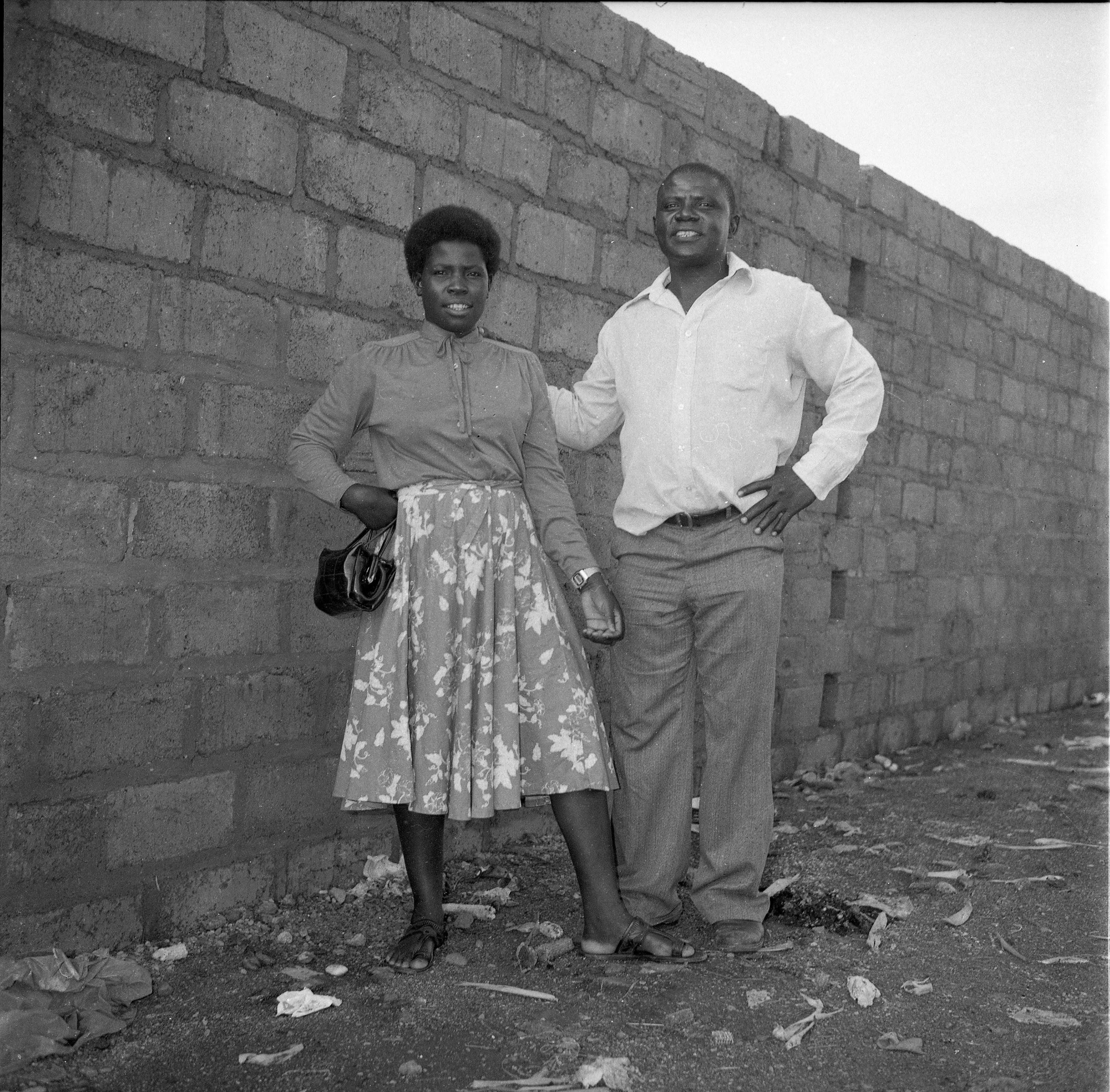

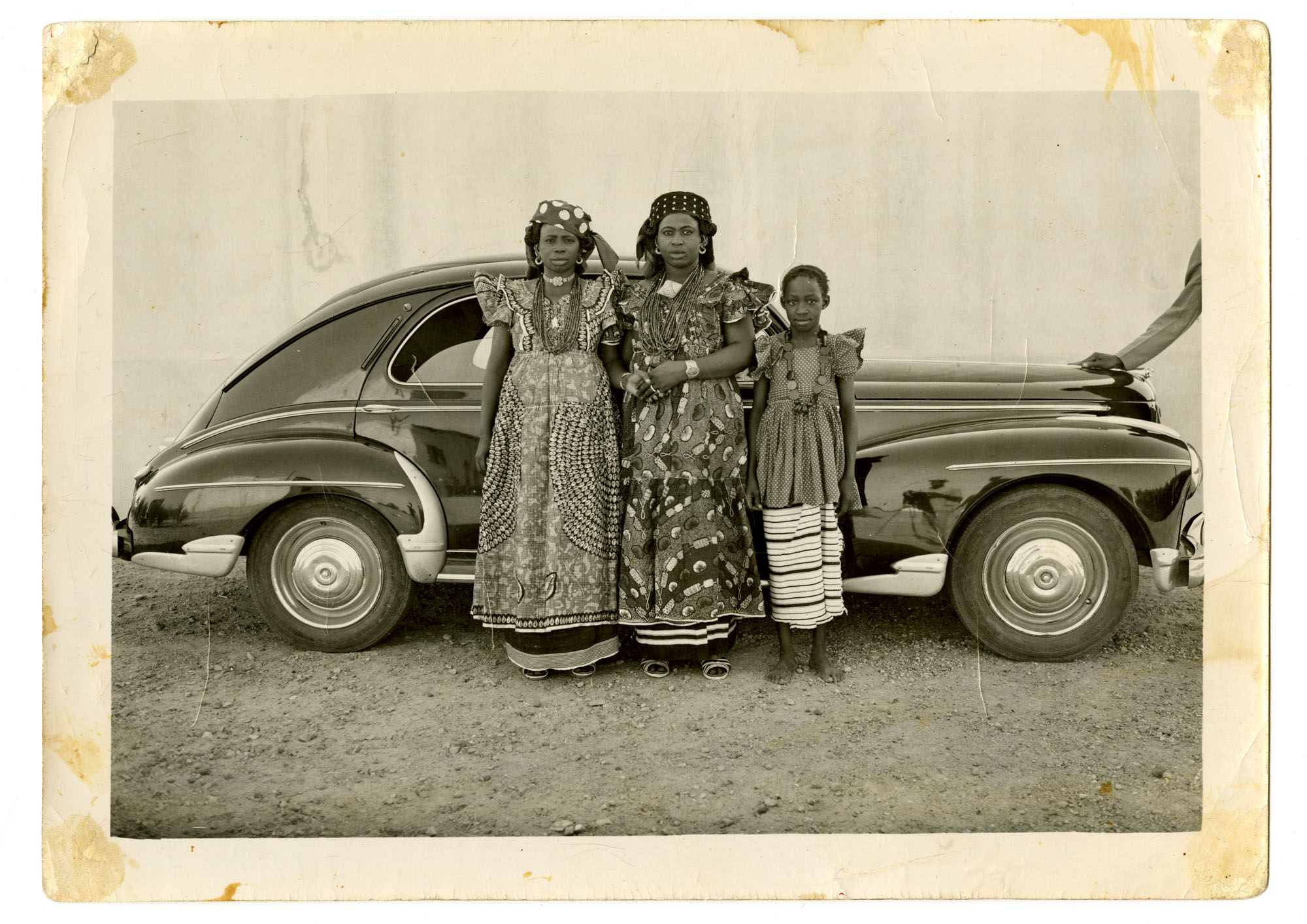

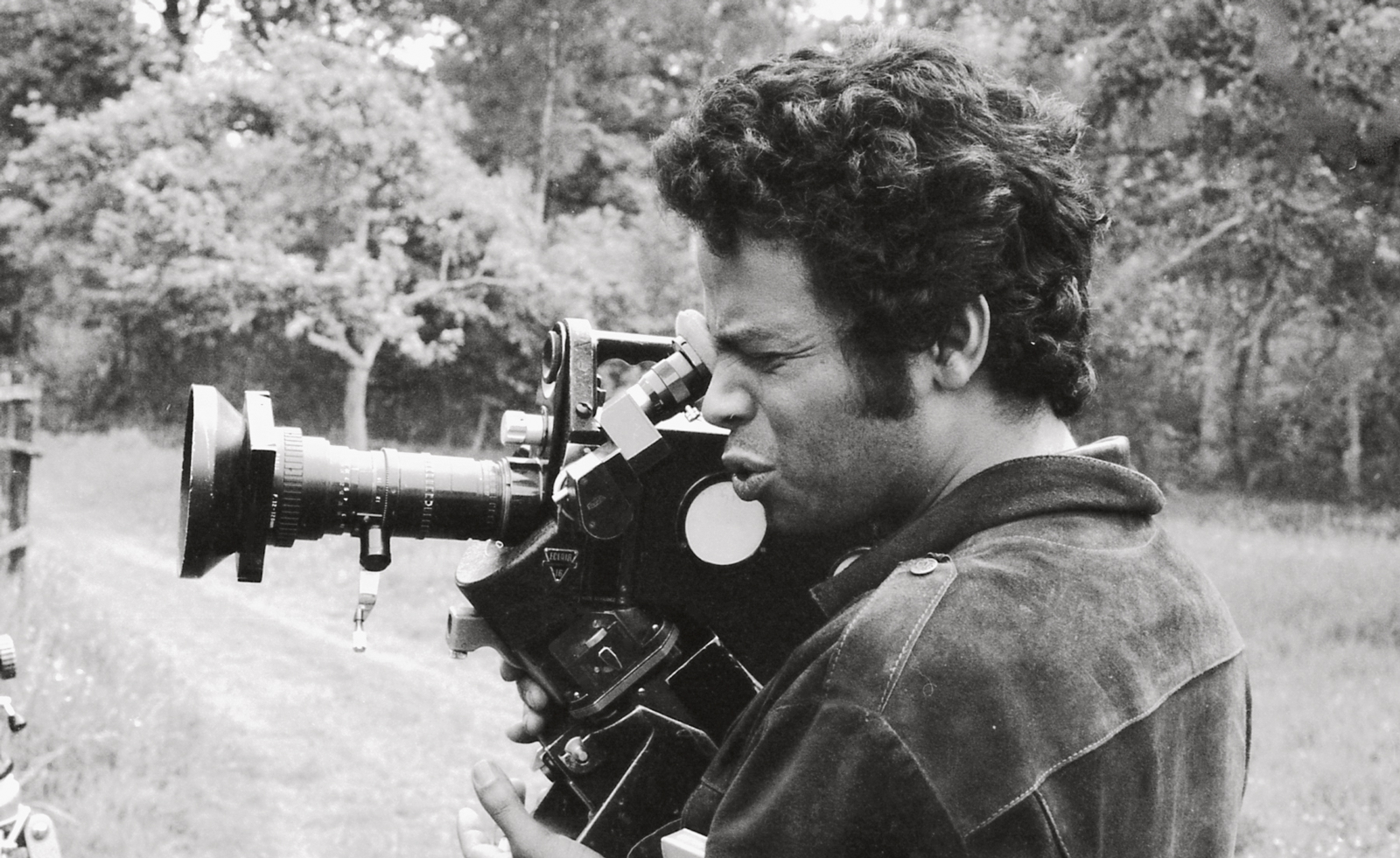

Understanding the creative legacy of Alick Phiri seems like grasping a light through the slats of history, through old images that convey nostalgia, the fleeting brilliance of photographs that define the zeitgeist of life in the 70s and 80s Lusaka society where the photographer captured people and emotions. During the mid to late twentieth century, photography was limited to Black Zambians due to the lingering effects of colonialism and apartheid-era dynamics in southern Africa. This made professional photographic equipment so inaccessible to purchase.

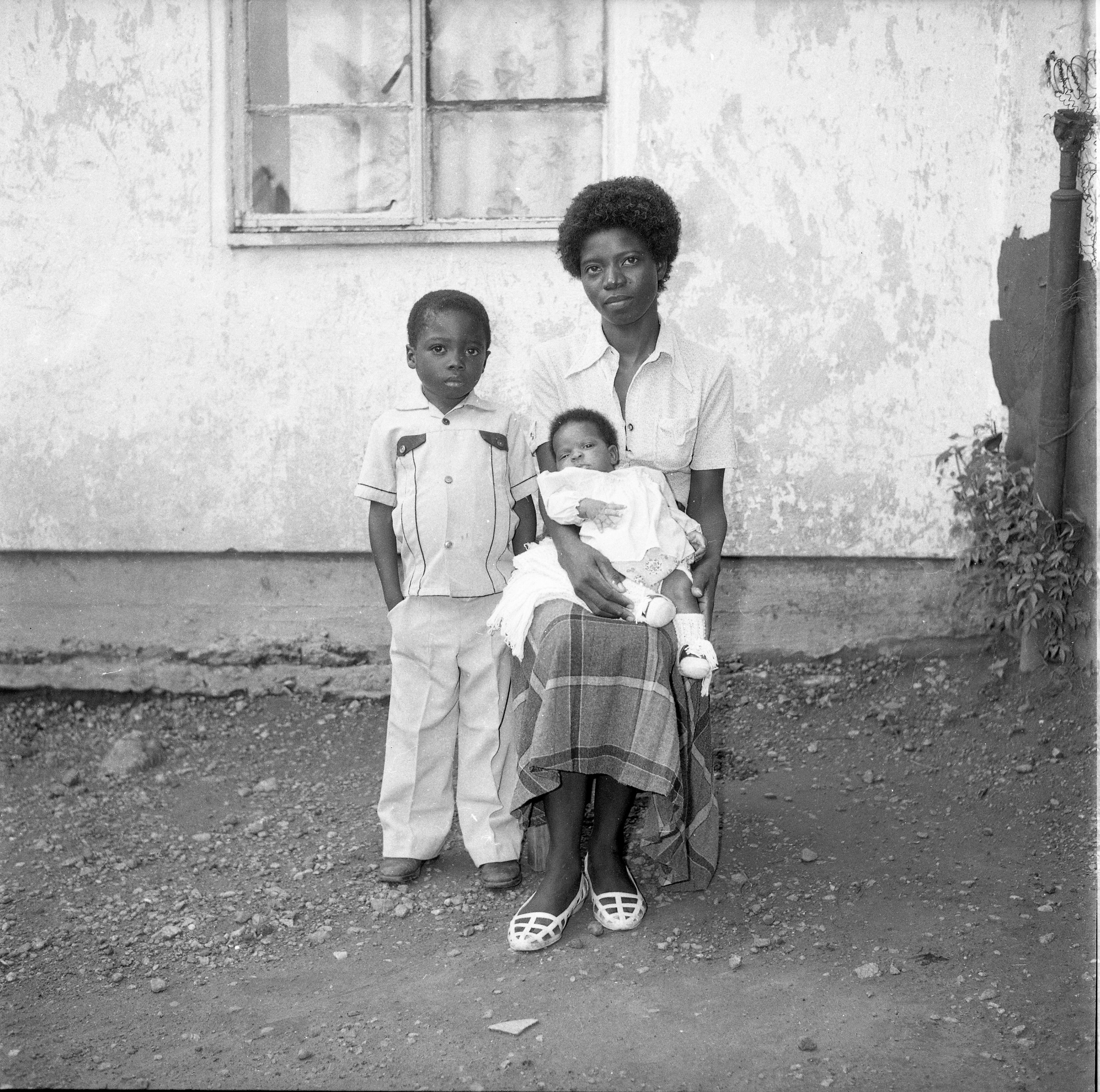

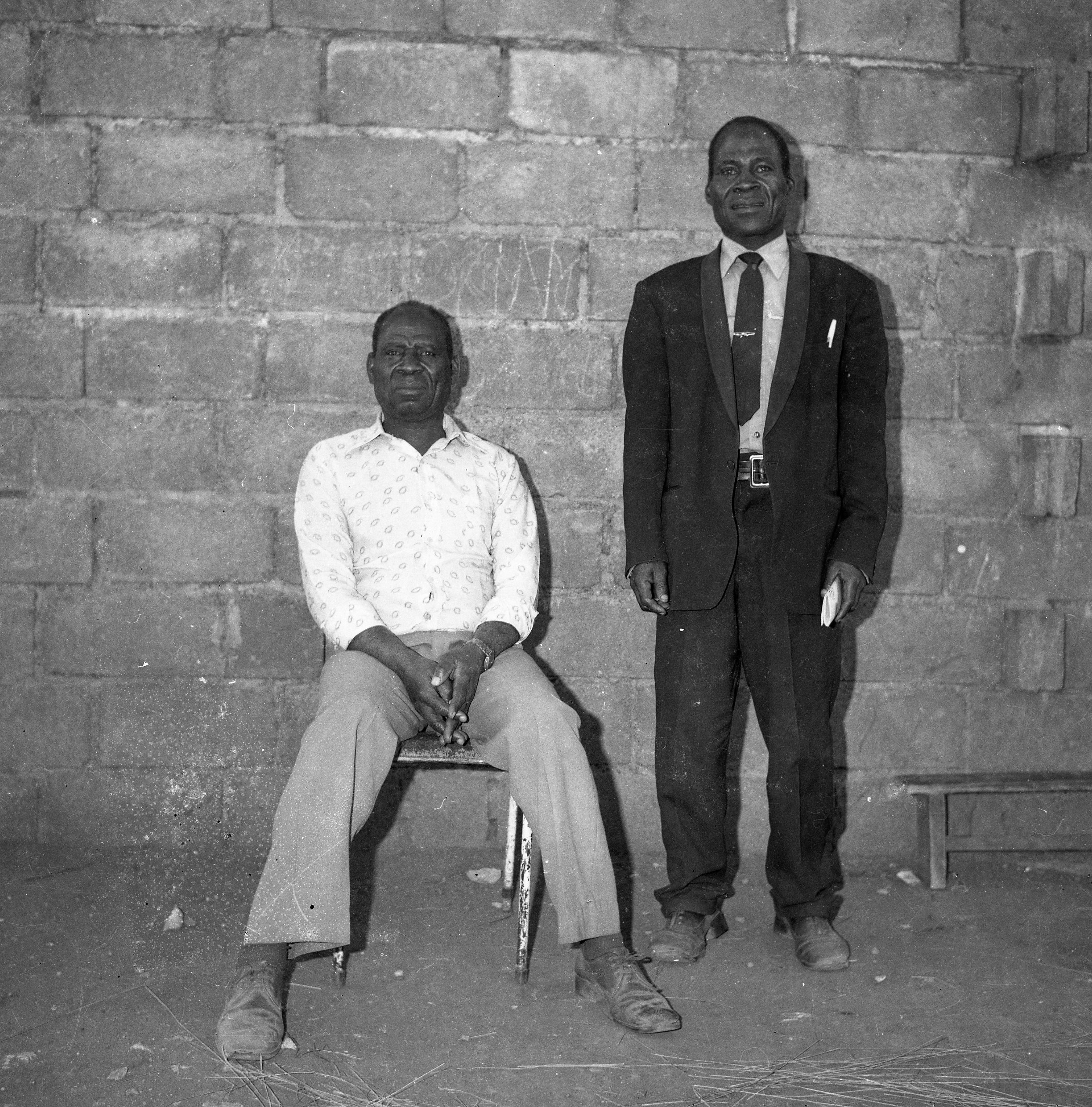

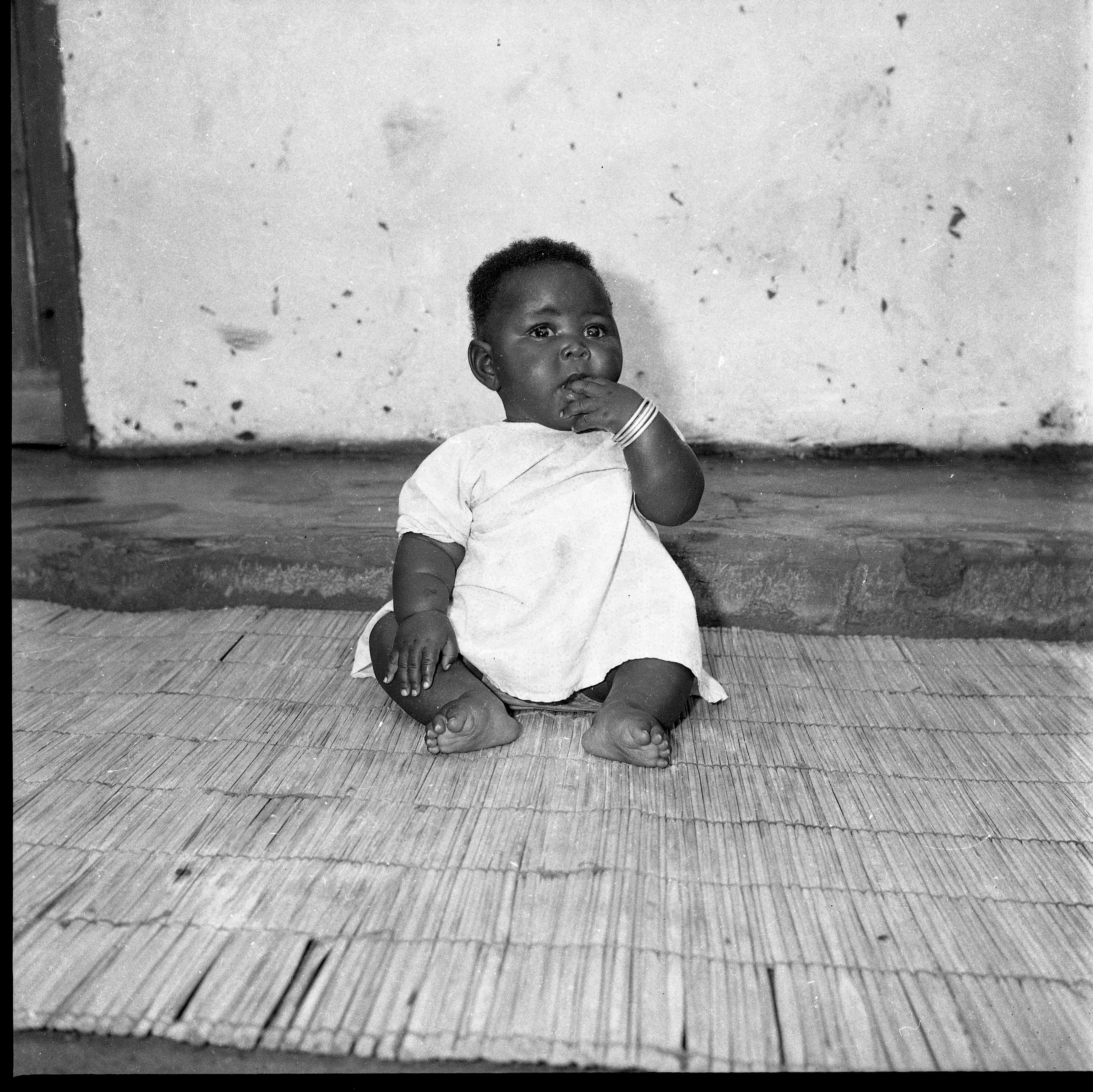

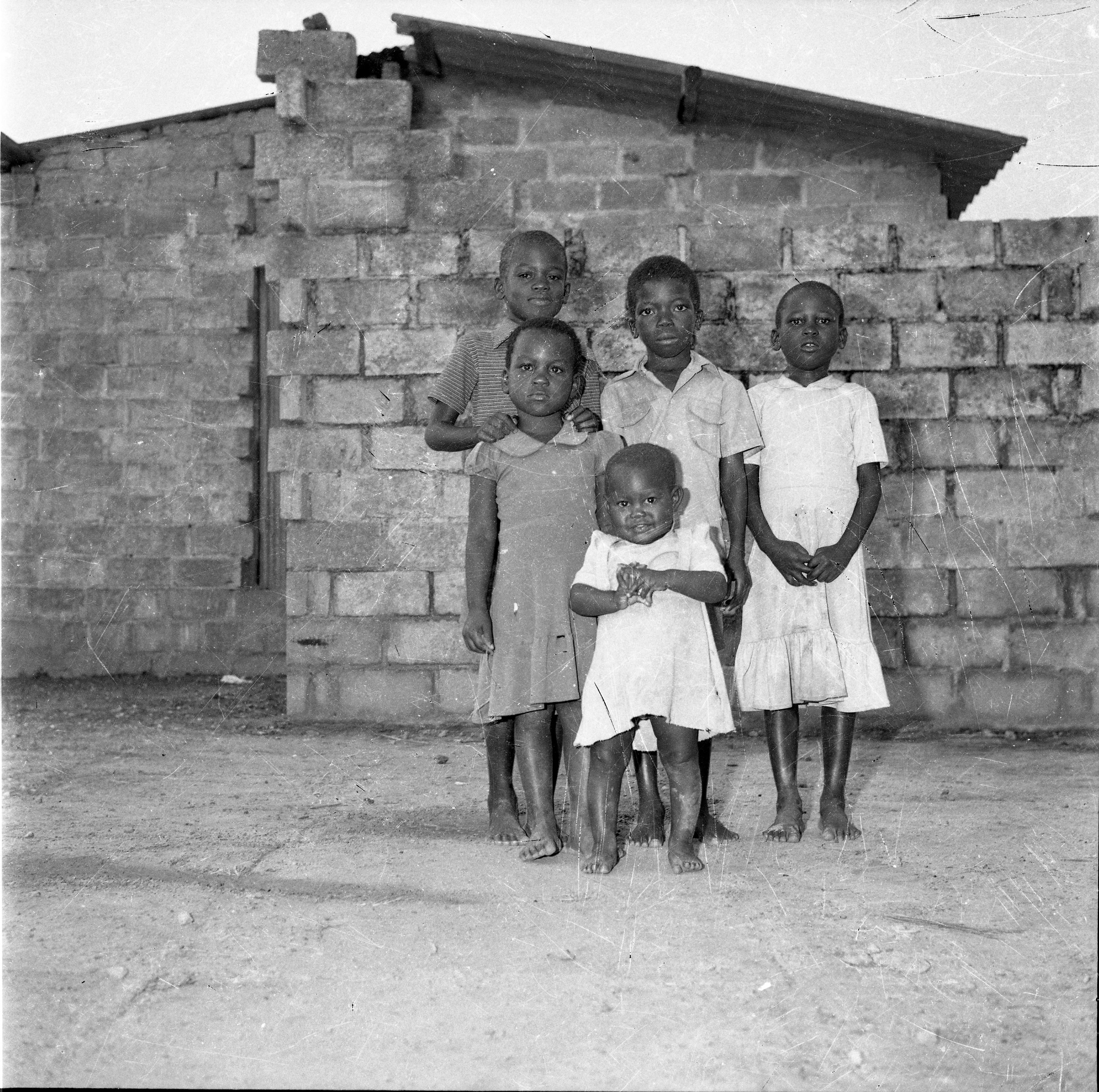

However, Phiri found his own way forward, tutoring under Mr. Prabhubhai Patel at Lusaka's Photo Art Studios, where he learnt the concepts of photography and film production. By 1983, Alick launched his own studio: 'Kwacha Photo Studio', in Kanyama, Lusaka where his focus lay in making black and white portraits for families, images that would come to describe post-colonial Zambia featuring siblings in well-tailored uniforms, twins in corporate outfit, a mother and her children and a large portrait of extended families.

In respect to celebrating his legacy, an exhibition featuring his works alongside South African photographer William Matlala is currently open at Everyday Lusaka gallery. Titled I’ll Be Your Mirror the exhibition reflects on both photographer’s archives, sparking conversation about their careers and spotlighting that classic feel. 'After Mr. Patel passed away a few years ago, I felt a sense of urgency in showing Alick Phiri’s work during his lifetime,' says curator Sana Ginwalla. 'In a time when Lusaka’s landscape and population is rapidly growing on a daily basis, I wanted to offer a moment of reflection of what the city and its residents looked like in the past and honour the work of photographers like Alick who documented this.'

Alongside the exhibition is the debut photobook by Alick and Sana Ginwalla titled Lusaka Street, the inaugural photo book of archival street photographs made in Lusaka. Ginwalla’s intention was to honour the generational links between Mr. Patel, Alick Phiri, Fine Art Studios and Zambia Belonging. 'As an Indian-Zambian, I wanted to spotlight these otherwise unacknowledged modes of allyship that the Indian community in Zambia had contributed to in colonial Northern Rhodesia. Zambia Belonging would have never become realised, and I would not have met Alick if Mr. Patel had not started Fine Art Studios in the 1950s,' she says.

I’ll Be Your Mirror marks Alick Phiri’s public debut in Lusaka.

In Conversation With Alick Phiri

Wallpaper*: What drew you to photography?

Alick Phiri: My cousin had a small cheap camera. He used to give me that to play around. Then one of these Indian boys I played with saw me with the camera and said, 'ah, you take pictures?” He showed me a place to get it developed and I left it there. Then after leaving it, the next day I came to collect it. So, he (Mr. Patel) became interested in me, you see. I was very small at the time. He asked me if I wanted to be a photographer. I said yes. At the time I used to play guitar. Mr. Patel said to me, “ah, this is not your line”. I said, “I want it”. Mr. Patel used to play the piano. I asked myself, “ah, he's playing piano, now why shouldn’t I play guitar?”. So later on, he said, I'll teach you better things. That was photography. He took me to school, by then it was £1.50 for tuition. I went to Kamwala Primary School, and I took evening classes.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

W*: Describe your family background, what were your earliest artistic experiences in Zambia?

AP: When I first moved to Lusaka, I used to play with a number of Indian boys outside Limbada Hardware opposite the UNIP office – when President Kaunda would come, I used to explain who the different people were, and the children enjoyed that. When they went to school, when they asked them questions, they knew who the people were. So that's how I came up with them. I enjoyed staying here. In fact, I learned a lot of things, you see. When you have a problem, you learn a lot of things, and obey the old people.

W*: Prior to starting your photography career, you interned for Mr. Prabhubhai Patel, how did that shape your own career?

AP: At that time, being the youngest man at the Photo Art Center, there were white people that would look at how small I was and they didn't want me to take their photo. They were always unsure of me. Mr. Patel would come near me and guide me on the process and what exposures to use whether it was a Black man or a white man. Whenever I photographed white clients, Mr. Patel always told me to take two or four pictures for them because they were quite troublesome, you see, so I started taking two.

Then after taking it, I process it, I bring it to Mr. Patel, who would look at them and decide. Then he’d go into the darkroom, print it and everything, then he came to me, and showed me the result. When we’d come to the client, they’d say, “you took a very good picture.” They wouldn't know that the process was done by the boss. That's how I went into photography.

W*: You lived in Zimbabwe earlier on, did it partly inspire your passion for photography?

AP: No, but there were a number of photographers from Lusaka going to Zimbabwe for photography. South Africans also were coming to Zimbabwe. Black Zimbabweans were a bit higher than ourselves regarding prestige. Most of these Zambian journalists and photographers went to Zimbabwe and they were coming first place in competitions when they went there. Black Zimbabweans were at a higher status than we were as Black Zambians. In fact, higher than the Black South Africans because the white people there thought that they were the only ones who can do photography. So, Africans were overlooked. I'm sorry to say this, but this is fact.

W*: You opened your studio in the 80s, what services were you offering?

AP: I was taking black and white photos, it was more accessible. To develop colour photographs, we used to send the film to East Africa or Bulawayo. Nobody did that here. It was much later when the Colour Photo Company started processing colour photos on Lumumba Road.

W*: Was finding your studio a means to break colonial and racial boundaries?

AP: It was the next step in my career as a photographer. We had a few Black Zambian and Congolese studios. I remember very well, we had two Congolese in Chilenje having their own studios. We had three in Chaisa Market, one in Mandevu Market, and one in Kanyama, which was me.

W*: Aside from documenting everyday Lusaka, what other things did you capture?

AP: I didn’t take pictures of anything other than people. Photographing people in the street was a bit difficult because you have to get a deposit from them. If you don't get a deposit, you won't see them again. They’re gone for good, you lose out on the film. The studio was much better because when they come to the studio, I take the money straight away. The next day, they collect their picture. Most of the time, when it’s holiday time or the weekend, I used to do it all the same day and give it to them..

W*: As one of the pioneering photographers in Zambia, how does it make you feel that you have built an important legacy for younger generations?

AP: I feel very proud to see my work. My wife didn't think much of most of the pictures at home – she was thinking that they’re useless. So I had to take everything and put them in a photo album to preserve them. We thought, “ah, this is rubbish.” I didn't know.

'’ll Be Your Mirror' is at Everyday Lusaka Gallery, Zambia until 9 August, 2025

-

Mickalene Thomas and Tom Wesselmann consider the female nude in Palm Springs

Mickalene Thomas and Tom Wesselmann consider the female nude in Palm Springs'The Female Form: Tom Wesselmann & Mickalene Thomas from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation' places the artists' work in cultural context at Palm Springs Art Museum

-

Prada’s A/W 2026 menswear show was about excavating the past to find the future

Prada’s A/W 2026 menswear show was about excavating the past to find the future‘It’s a kind of archaeology,’ said Raf Simons of his and Miuccia Prada’s latest menswear collection, which was presented at Fondazione Prada yesterday in Milan

-

‘The Iconic Nordic House’ explores the art, craft and influence of the region’s best residences

‘The Iconic Nordic House’ explores the art, craft and influence of the region’s best residencesA new book of Nordic homes brings together landmark 20th-century residential architecture with stunning contemporary works; flick through this new tome from Bradbury and Powers

-

Inside the work of photographer Seydou Keïta, who captured portraits across West Africa

Inside the work of photographer Seydou Keïta, who captured portraits across West Africa‘Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens’, an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, celebrates the 20th-century photographer

-

‘It is about ensuring Africa is no longer on the periphery’: 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London

‘It is about ensuring Africa is no longer on the periphery’: 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in LondonThe 13th edition of 1-54 London will be held at London’s Somerset House from 16-19 October; we meet founder Touria El Glaoui to chart the fair's rising influence

-

Love, community, anti-gay laws: the queer African artists redefining visibility through portraits

Love, community, anti-gay laws: the queer African artists redefining visibility through portraitsIn honour of Pride Month, Ugonnaora Owoh speaks to three artists on African queer legacies and their optimism in advocating for queer rights through art

-

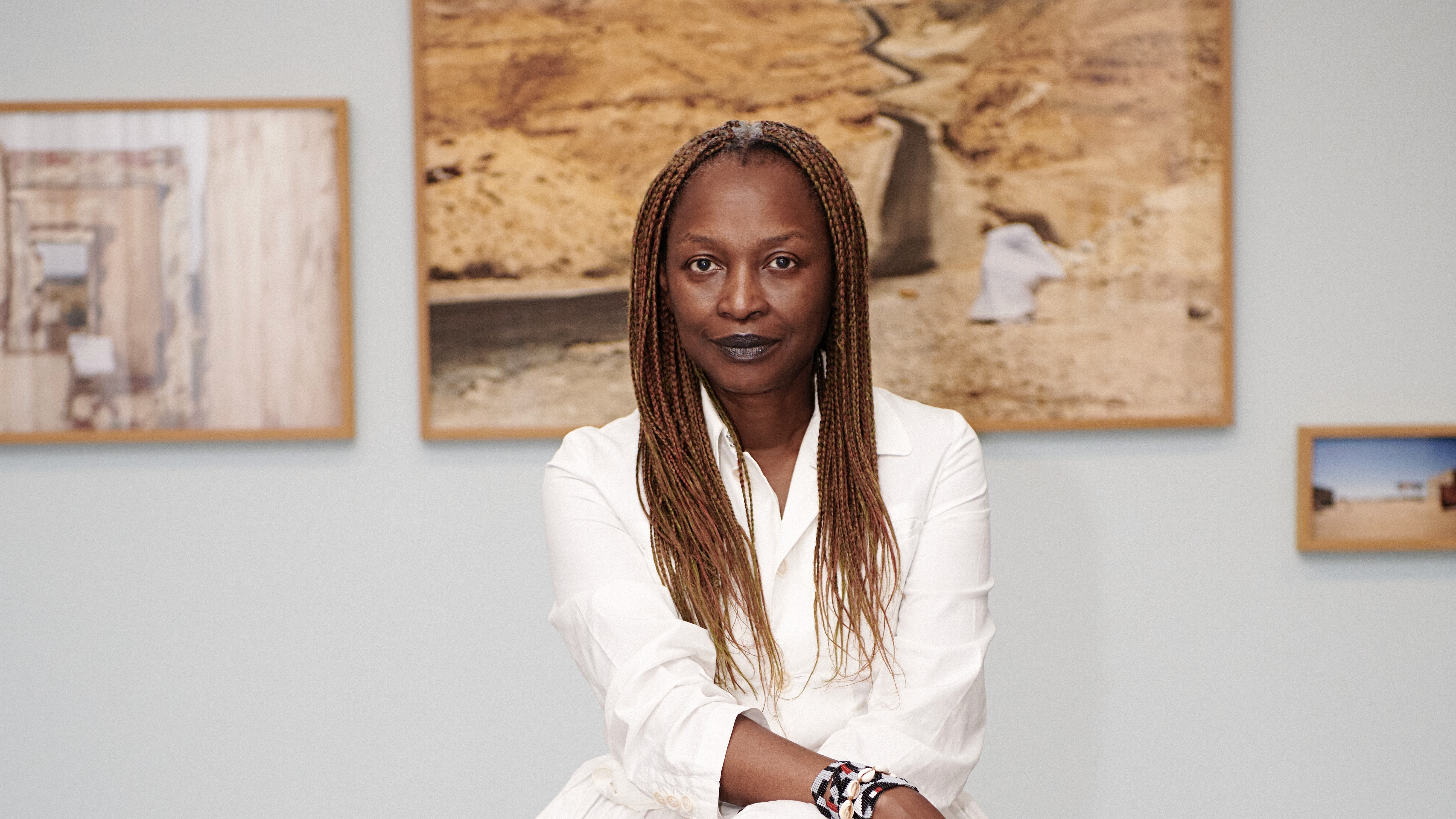

Remembering Koyo Kouoh, the Cameroonian curator due to lead the 2026 Venice Biennale

Remembering Koyo Kouoh, the Cameroonian curator due to lead the 2026 Venice BiennaleKouoh, who died this week aged 57, was passionate about the furtherance of African art and artists, and also contributed to international shows, being named the first African woman to curate the Venice Biennale

-

Inside Yinka Shonibare's first major show in Africa

Inside Yinka Shonibare's first major show in AfricaBritish-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare is showing 15 years of work, from quilts to sculptures, at Fondation H in Madagascar

-

Don’t miss these artists at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair 2024

Don’t miss these artists at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair 2024As the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair returns to London (10-13 October 2024), here are the artists to see

-

How Amy Sall is highlighting the beauty of African cinema

How Amy Sall is highlighting the beauty of African cinemaAmy Sall is highlighting the cultural impact of African filmmakers with ‘The African Gaze: Photography, Cinema and Power’, published by Thames & Hudson

-

Ghana’s artists celebrated in new book by Manju Journal

Ghana’s artists celebrated in new book by Manju Journal‘Voices: Ghana’s artists in their own words’, from Manju Journal, celebrates 80 Ghanaian creatives