How Amy Sall is highlighting the beauty of African cinema

Amy Sall is highlighting the cultural impact of African filmmakers with ‘The African Gaze: Photography, Cinema and Power’, published by Thames & Hudson

In 2016, writer and researcher Amy Sall started teaching a course at The New School, titled ‘The African Gaze: Visual Culture of Post-Colonial Africa and the Social Imagination’. An introductory but critical study, the course offered a deep dive into African photography and cinema from the mid-20th century to the modern day.

‘At the end of 2020, I wanted to make the work more accessible because I realised there was such a strong demand and interest in material on African visual culture,’ says Sall. ‘When people heard about the course, they wanted to have my syllabus and sit in my classes.’

After releasing the syllabus to outstanding public response, Sall embarked on a journey to create a wider and more inclusive conversation. The result is a 288-page book, a collection of striking images and comprehensive text on some of the continent’s greatest photographers and filmmakers, named The African Gaze: Photography, Cinema and Power.

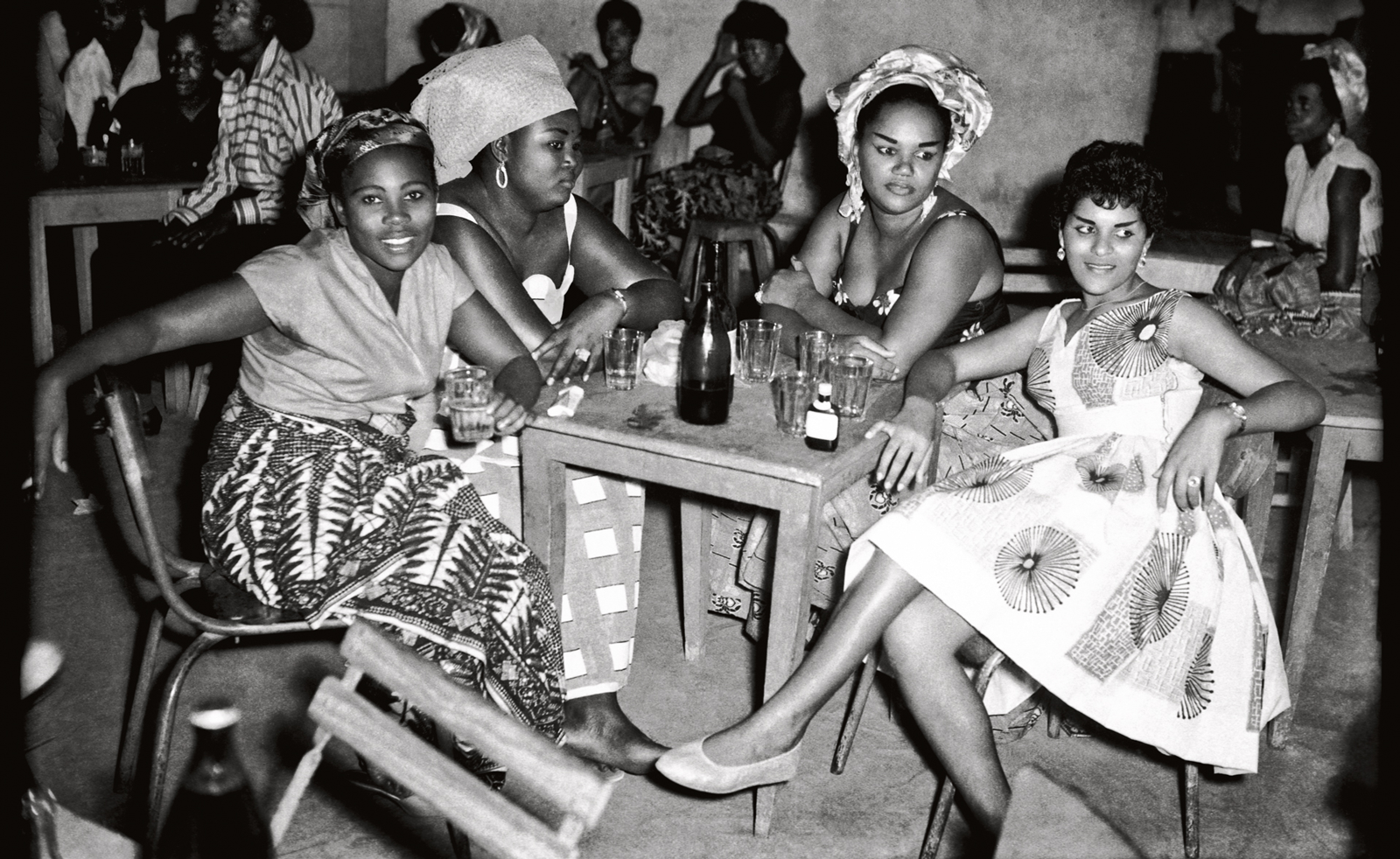

Filles du bar-dansing, Léopoldville, 1955-65

Based on a pan-African perspective, the book documents the depth of the continent’s visual culture, dating as far back as the time of colonial rule and the postwar period, to the postcolonial era and beyond. Concise chapters illuminate significant cultural moments through the lens of some of Africa’s best, including James Barnor’s exploration of Ghana’s city life before and after independence, Ernest Cole and his visual commentary on the harsh realities of Black South Africans in the Apartheid regime, and Samuel Fosso’s gender-bending self-portraiture in 1970s Cameroon.

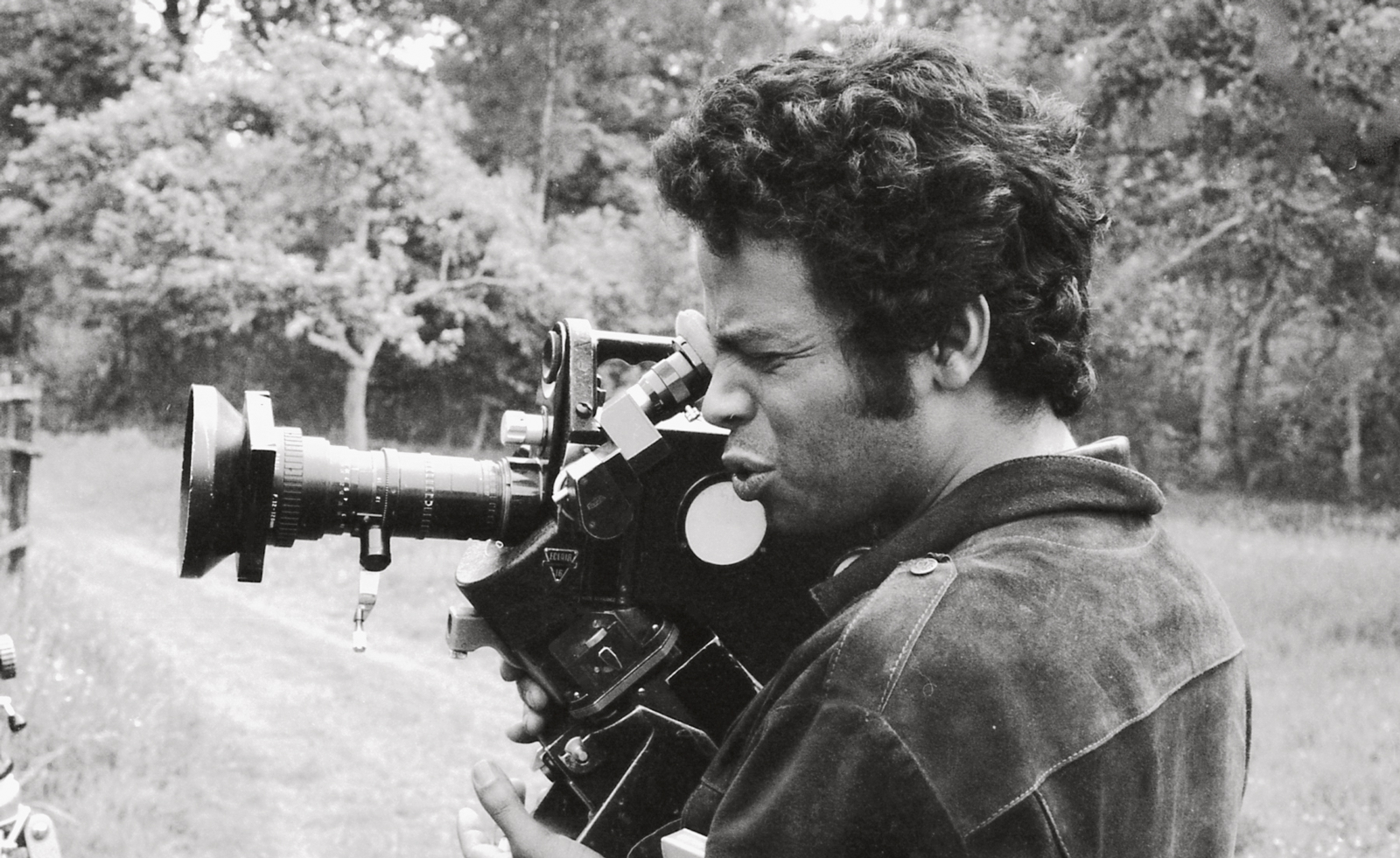

Beyond photography, The African Gaze cuts across the world of cinema, highlighting the social, political and cultural impact of filmmakers, from Ousmane Sembène and his dedication to depicting the postcolonial climate exactly as it was to Souleymane Cissé‘s pushback against flawed, Eurocentric depictions of Africans. ‘The colonial photographic framework positioned Africans as being uncultured and tried to extract their humanity, but from Africa’s image-makers we see the breadth of the human condition and everything in between,‘ remarks Sall.

Sall’s love for African visual culture deepened in grad school, where she took an ‘incredible, life-changing’ pan-African course by Columbia University professor of West African history, Mamadou Diouf. Between this and her self-study on African visual materials, the author realised the need to create a space where people who had an interest in cinema, photography, literature and human rights issues on the continent could gather to share and discuss archival material.

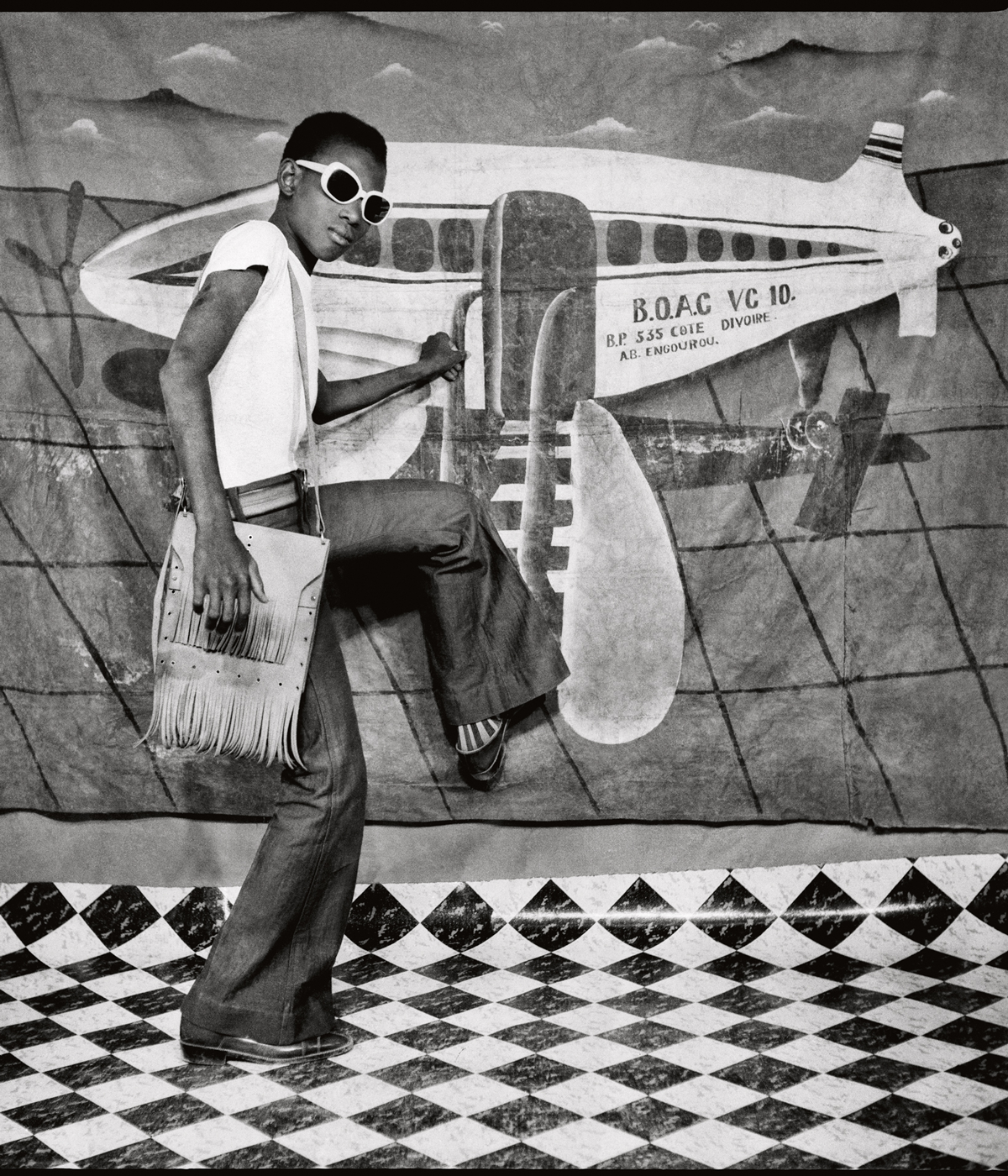

Je vais décoller, 1977

As a reflection of all her interests, she later launched SUNU Journal, a platform where young scholars and creatives who had something compelling to say about Africa could showcase their work. ‘I value all of the culture and history across Africa, so I knew that there were people like me who would be interested in the same things.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

This desire to promote culture while protecting it plays a major role in ‘The African Gaze’. Aside from making memories and documenting history, many of Africa’s pioneer visual artists highlighted the importance of self-preservation. ‘Before these works became a part of the Western art world, they circulated privately amongst family members and friends to be framed and hung up on walls in the privacy of the home,’ Sall affirms. ‘They are not just pieces made for galleries or museums, but they serve a personal, sacred function.’

In recent years, these works have been distributed widely across the art market, and although Sall agrees that the language of photography and cinema is a universal one, she also believes that the level of commodification within the industry brings a sense of loss around significant work. ‘These days, there are dealers and gallerists who go to Africa to buy photographs in bulk from small cities and villages, looking for imagery from family members of popular image-makers to take back to galleries in the US and Europe,’ Sall explains.

Self-portrait, from 1970s Lifestyle series, 1975-78

This extractive practice, she suggests, leads to a situation where the work is appreciated more for its aesthetic value rather than the deeper meaning intended by the original creators. ‘It’s a sort of double-edged sword, because while more people are discovering these photographs, there are deeper levels and underlying ideas embedded in them that tend to be overlooked,’ she goes on. ‘It’s about what this means to our culture and people, and what we can learn from the work beyond its beauty.’

For Sall, engaging with African photography and cinema means deepening one’s knowledge and research, and not merely consuming for consumption’s sake. ‘No matter what your practice is, whether literature or art, people can be inspired in some way by the image-makers who were known for taking great risks,’ she says. ‘A lot of them faced bans or had to go into exile because their messages were so profound, going against neo-colonial governments and staking their claims fearlessly.

‘Overall,’ she concludes, ‘I hope that the boldness of these image-makers also inspires some of today’s creators.’

The African Gaze: Photography, Cinema and Power'by Amy Sall is published by Thames & Hudson

Marris Adikwu is a culture writer with a special interest in art, fashion and music. Her work has been featured in Vogue Magazine, Billboard, New York Magazine, and more