Disruptive nonagenarian Julio Le Parc is still making waves

We caught up (virtually) with the trailblazing Argentine artist to discuss bureaucracy, defying categorisation and his latest wave of optokinetic art

Claire Dorn - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

One morning in the early days of France’s national lockdown in the wake of the Covid-19 outbreak, Julio Le Parc is sitting in his studio in Cachan, south of Paris. ‘I’m here, waiting,’ complains the 91-year-old Argentine artist over the phone, like the unwilling character of a Beckett play.

But in normal circumstances, Le Parc isn’t one to wait around. Upon emigrating in the late 1950s, the Op Art master was quick to make his mark in the French capital, where he has continued to captivate and challenge the establishment in equal measure. Since then, his large-scale kinetic sculptures and rainbow-coloured geometric paintings have been exhibited around the world, including in solo exhibitions at the Serpentine Galleries in 2014 and at the Met Breuer last year. Now, in anticipation of a post-pandemic exhibition at their New York outpost, Galerie Perrotin is launching an online viewing room for the summer.

Julio Le Parc, photographed in his studio in Cachan in February 2020, with artworks from his Surface-couleur series. Photography: Claire Dorn. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

The son of a railroad worker, Le Parc grew up in the western-central city of Mendoza, on the eastern side of the Andes. In the 1940s, after his parents separated, he relocated to Buenos Aires where he attended a weekly sculpture module taught by Lucio Fontana for a foundation course at the School of Fine Arts. ‘We’d listen to his ideas on spatialism,’ recounts Le Parc, the only student of the cohort who refused to sign the great Italian artist and theorist’s White Manifesto, over principles of authorship. While an entire generation of Latin American artists were advocating the figurative ideals of the Mexican muralists à la Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, Le Parc turned his interest to abstraction, favouring the geometric forms and bold colours popularised in Argentina by the Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención.

Unlike the muralists, who relied on figuration to address social injustice, Le Parc and his peers were interested in the radical potential of an unmediated encounter between the artwork and the viewer. ‘We were aware of Kandinsky, Mondrian and the Constructivists in general,’ recounts the nonagenarian artist. But it wasn’t until 1958, at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires, that he came across the work of French-Hungarian artist Victor Vasarely, the grandfather of the Op Art movement. ‘My friends and I were very impressed,’ he says of the optical tricks played by the emblematic black-and-white checkerboard paintings. ‘It was very strong.’

Categories, in general, are reductive. I would prefer to be classified as an experimentalist

Thanks to a grant from the French government, Le Parc moved to Paris that same year. There, he became acquainted with Vasarely and a group of young, like-minded artists, including François Morellet, Francisco Sobrino and Horacio Garcia Rossi. Together, and with the help of others, they formed in 1960 the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV), an artist collective which advocated against the mystification of the solitary artist, favouring instead the audience’s active participation through the use of optokinetic forms. After the group’s dissolution in 1968, Le Parc remained a key representative of Kinetic Art: a label which he, however, has little patience for. ‘Categories, in general, are reductive,’ says the artist, who received his first solo exhibition at the now-defunct Howard Wise Gallery in New York in 1966, the same year he was awarded the painting prize at the Venice Biennale. ‘I would prefer to be classified as an experimentalist.’

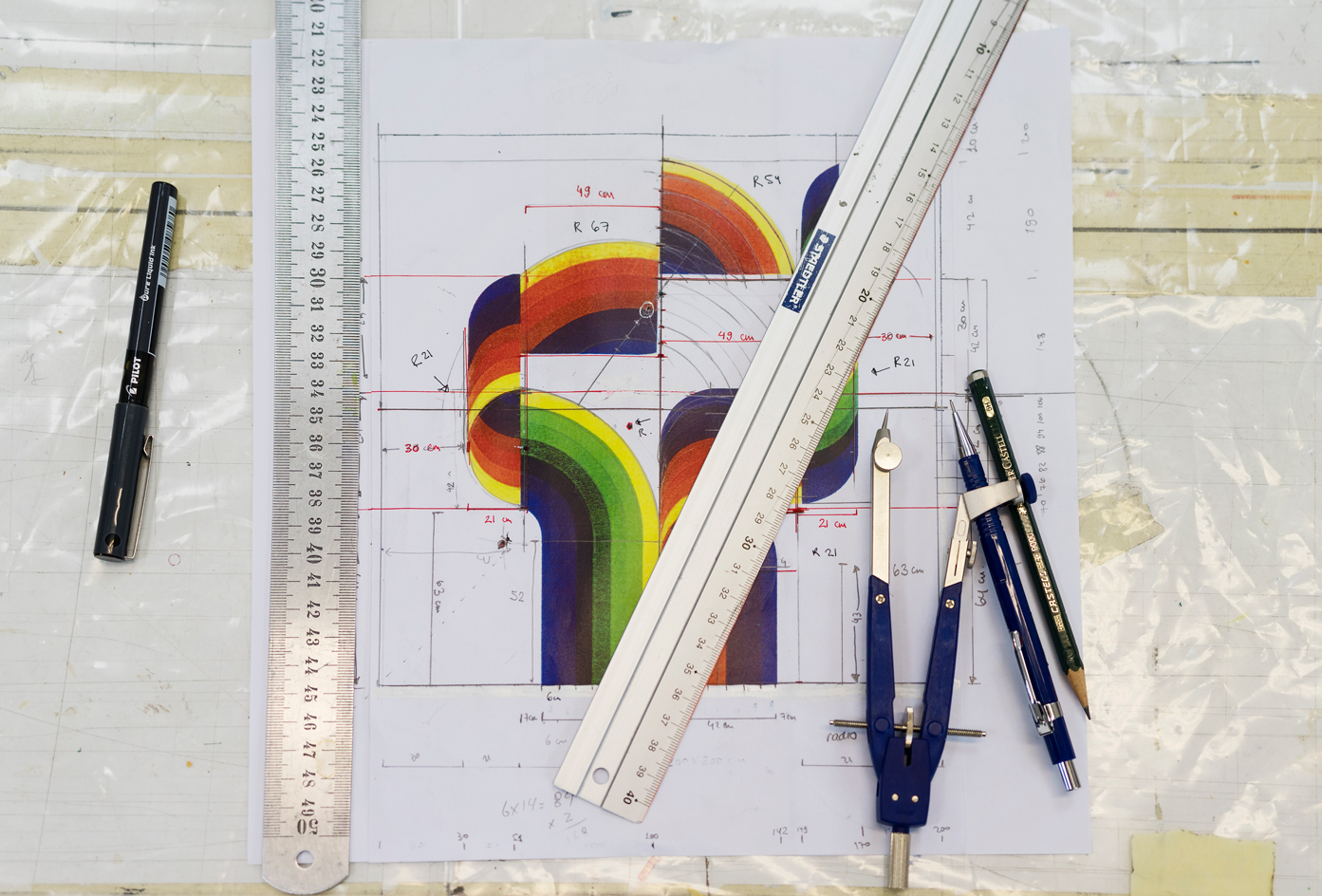

Artworks from Julio Le Parc’s Surface-couleur and Alchimie series. Photography: Claire Dorn. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Indeed, Le Parc’s taste for experimentation has shaped much of his oeuvre up to this day. He first introduced light into his work in 1959, resulting in the moving-light installations he is now best known for. They include the kinetic relief Continual Mobile, Continual Light from 1963 (part of the Continual Mobile series) in which mirror-plate squares attached to nylon threads hang from a thin metal plate, creating optical effects made of shadows dancing against a white background. Meanwhile, Continual Light Cylinder (1962-2019) is a series of unique, site-specific kinetic sculptures that project light reflected through a volumetric form, altering the environment of the gallery. Through their use of light and movement, these works call on the viewer’s engagement in ways that are at once playful and disruptive.

Today, Le Parc is considered a national treasure in France, where he was decorated by the ministry of culture as an Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. But it wasn’t always the case. Much like his artistic practice, the enfant terrible has gained a reputation as a disruptor. In the wake of the civil unrest in 1968, he was briefly expelled from the country for his involvement in the occupation of a Renault factory. Then, in the 1970s, not only did he turn down a solo exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne on a coin flip (which, he assures me, he never regretted), but he was at the forefront of an artists’ protest group against the management of the nascent Centre Pompidou. ‘I thought they had to invite the artists to discuss their plans and ideas,’ he tells me, recounting how the museum’s founding director, Pontus Hultén, preferred befriending a coterie of top-notch galleries. ‘It wasn’t against the Centre Pompidou,’ Le Parc adds, ‘but it seemed important to me that the museum built relationships with artists living in Paris.’

Spray guns (tools for the creation of artworks). Detail of Julio Le Parc's Studio. Photography: Claire Dorn. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Does he think the art bureaucracy he so distrusted has improved since? ‘The situation is worse,’ he responds categorically. ‘Artists don’t have a say in the decision-making process. The market is practically the only system that gives value to contemporary creation. In my view, we need to find new ways of assigning value. Otherwise, the power stays in the hands of the rich, and in the majority of cases, institutions internationally adhere to that system.’ We’ll have to see if such a paradigm shift becomes conceivable in the post-pandemic era. But for now, and despite his longstanding efforts, Le Parc continues to wait.

This is an extended version of an article originally featured in the May 2020 issue of Wallpaper* (W*254) – on newsstands now and available for free download here

INFORMATION

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.