Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

The penis paintings of Tom Wesselmann exist in strange spaces in-between; at once figurative and abstract, somewhere between the mainstream pop art and the counterculture of ‘porno chic.’ This moment in American film and culture, brought on through Blue Movie, a 1969 film by Andy Warhol (another pop artist), and lasting through to the 1970’s, saw sexually explicit and pornographic films enjoy a brief moment in the cultural spotlight, even being taken seriously as art; whether in the 1970’s adult films like Deep Throat and The Devil In Miss Jones, or arthouse films with sexually explicit content like Last Tango in Paris. It’s in this moment, of sexuality – and sexual explicitness – being taken seriously, that animates the work on display in Up Close, with Wesselmann challenging the limits of figurative painting, and the ways in which we might understand sexually explicit art.

Tom Wesselmann, Study for Bedroom Painting #13, 1968

At first glance, something like ‘Bedroom Painting #19’ (1969) is, irrespective of its subject matter – a penis spanning the majority of the canvas, with fragments of a rose and an alarm clock in the background – almost archetypally figurative, an extension of studies and nudes that have been part of art history for centuries up until this point. But by placing this nude in a more sexually explicit position and context, Wesselmann’s work veers towards the abstract, asking us to consider what it means to see a penis – at once a shorthand for so much symbolism of male domination, and sexual desire – as something divorced from the rest of the body, and without any kind of context in which it might exist. It becomes an erotic contradiction, at once able to be full of so much desire, and yet framed in a way that could be completely divorced of it.

It feels reminiscent of another Warhol film from the 60’s which explored the ways in which sex could be depicted on screen: Blow Job (1964), which presents the eponymous act but only through an extreme close-up on the face of DeVeren Bookwalter, leaving the act as something that viewers project onto his expression.

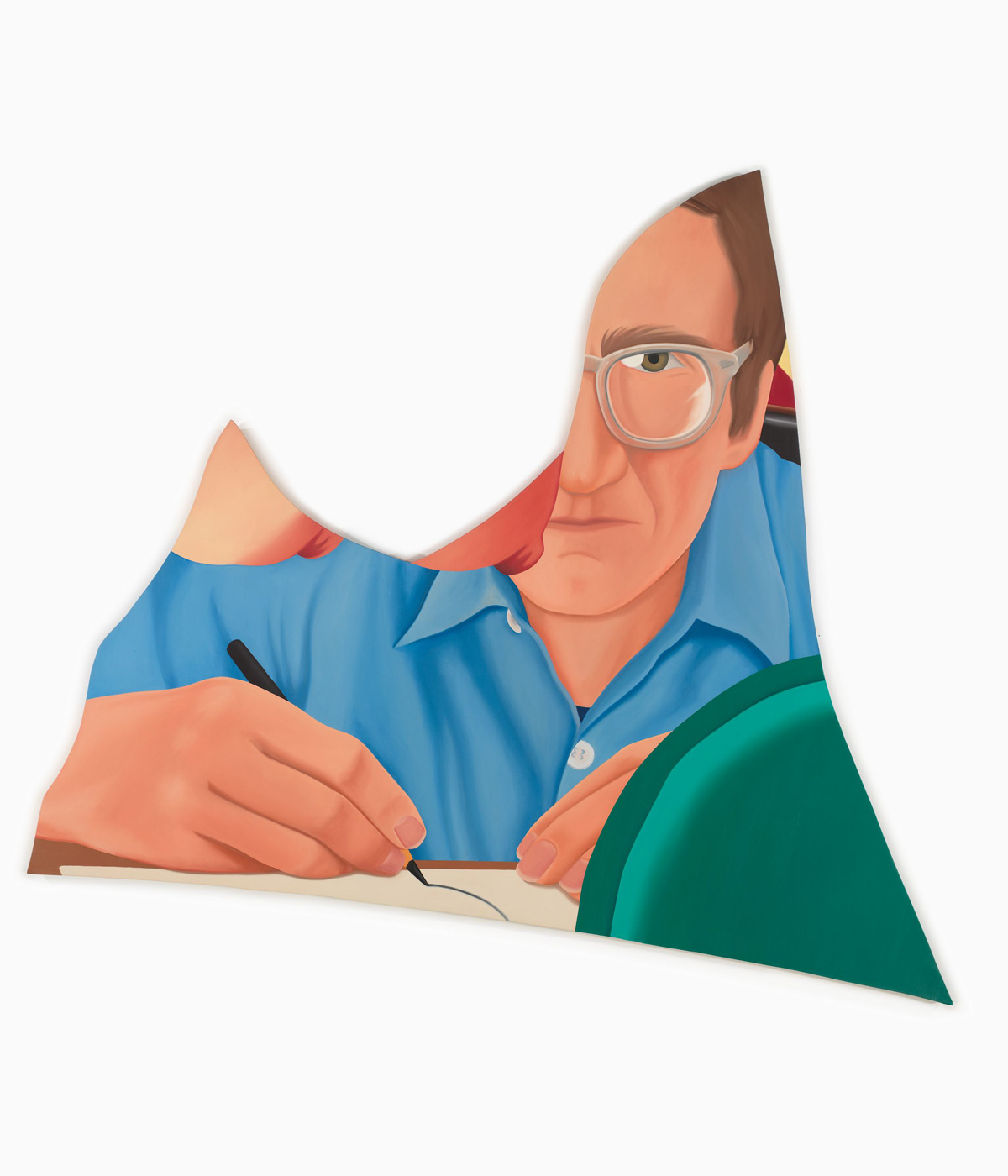

Tom Wesselmann,Self Portrait While Drawing, 1983

If anything, the idea of sexuality and pleasure in Wesselmann’s work can be defined through this very absence; in ‘Seascape #27’ (1967-69), the penis extends beyond the edge of the background itself, occupying an even more abstract space at the very edge of the canvas, leaving this lack – of context, of the rest of the body, even of physical space – as the place in which desire can be formed. This is where Wesselmann’s pop art sensibility is at its most interesting and effective; through their simplified forms and vivid colours, they become objects in the same way as the soup cans and comic strips of his contemporaries. Wesselmann takes the maxim sex sells and pushes it to the limit.

Installation view of Tom Wesselmann 'Up Close', Almine Rech London, 2025 / © 2025 The Estate of Tom Wesselmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York - Courtesy of the Estate and Almine Rech - Photo: Melissa Castro Duarte

It’s this movement to the limits of things – of form, figuration – that make Wesselmann’s paintings so compelling, and what gives them an almost cinematic language as it echoes the era of the golden age of porn. The vivid red, wide open ‘Cut-Out Mouth’ (1977) is another of Wesselmann’s extreme close-ups, one that also feels like its in dialogue with the landscape of adult film (knowing the context of his work, something like ‘Cut-Out Mouth’ feels like it immediately exists in association with a film like Deep Throat). Wesselmann uses the extreme close-up as to challenge the limits of this very language; so often on film, a close-up is used to bring us close to the interior world of a character, to provide intimacy, as well as having very specific uses in hardcore films.

Tom Wesselmann in the studio, 2003

The recurring background in so many of Wesselmann’s ‘Bedroom Series’ feels almost like a film set; a space that exists in a playful, symbolic way, with both ‘Bedroom Painting #19’ and ‘Bedroom Painting #30’ (1974) featuring a solitary, burnt out cigarette in an ashtray (another image commonly associated with phallic symbolism, and a post-coital pleasure). This idea is brought to even more abstract territory in his seascapes, which place the nudes outside of the bedroom – and therefore outside of spaces that would normally be associated with sex and desire – placing them against backdrops of skies, seas, and sand.

The dissonance between the object and the location in which Wesselmann places it leaves a linger question in the air: is this what you desire? Up Close isn’t interested in presenting Wesselmann’s work in a way that provides an answer to this question, instead offering a series of objects and fragments through which one can try and understand what it is that makes them desirable in the first place, and what can be done with that desire once awakened.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tom Wesselmann: Up Close until 12 April at Almine Rech

Sam is a writer, artist, and editor. Their publications include All my teachers died of AIDS (Pilot Press, 2020), and Search history (Queer Street Press, 2023). They are one of the co-curators of TISSUE, a trans literary events and publishing initiative based in London