Pioneering author Jean Rhys was hard to define. In London, artists give it a try

'Postures: Jean Rhys in the Modern World' at Michael Werner gallery sees artists from Kara Walker, Celia Paul, Hurvin Anderson, and Francis Picabia bring Rhys to life in a curation by Hilton Als

To truly understand Jean Rhys, it is perhaps easiest to take the writer in her own words. ‘I would never really belong anywhere, and I knew it, and all my life would be the same, trying to belong, and failing,’ she wrote in Smile Please, her posthumously published autobiography. ‘Always something would go wrong. I am a stranger and I always will be, and after all I didn’t really care.’

Celebrated as a pioneer of feminist and postcolonial literature, the Dominican-born Rhys’s vision continues to inspire a new generation of Caribbean voices today, including Jamaica Kincaid and Caryl Phillips. Perhaps more surprising, though, is her affinity with the visual arts: now her work finds new life at Michael Werner Gallery’s ‘Postures: Jean Rhys in the Modern World’, an exhibition curated by Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and critic Hilton Als. Drawn from archival research at Yale, the show brings together drawings, paintings, books, and archival material alongside works by artists such as Kara Walker, Celia Paul, Hurvin Anderson, and Francis Picabia, creating, ambitiously, a ‘collective portrait’ of Rhys’s life.

Kai Althoff “Untitled”, 2020

The first section comprises art that references Rhys’s childhood in Dominica. Reggie Burrows Hodges’s Crossing Roots (2025) presents an enigmatic encounter: a woman and a tropical scene emerge from black linen. Then there’s Anderson and Walker’s lurid paintings of the West Indies, and Cynthia Lahti’s Cousins (2005): a raku-fired sculpture of fourteen young girls on pedestals that form something like a dispersed family tree.

The next section deals with Rhys’ time in London, where she moved at sixteen, and the final section with Paris, where she would meet writer Ford Madox Ford. Under his tutelage, Rhys completed her first book in 1928, The Left Bank and Other Stories; the following year, she fictionalised their affair in Quartet. Through the 1930s she published After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, Voyage in the Dark, and Good Morning, Midnight: novels of haunted, lonely women – avatars of Rhys and her peripatetic life spent adrift in London, Paris, and Vienna – navigating poverty, leaning on drink and pills to endure their isolation. Dismissed by critics as beautifully written but bleak, Rhys withdrew to Devon until 1966, when she would publish her masterwork Wide Sargasso Sea: a reimagining of Jane Eyre through the eyes of the Creole Bertha Mason.

Hurvin Anderson “Untitled”, 2025

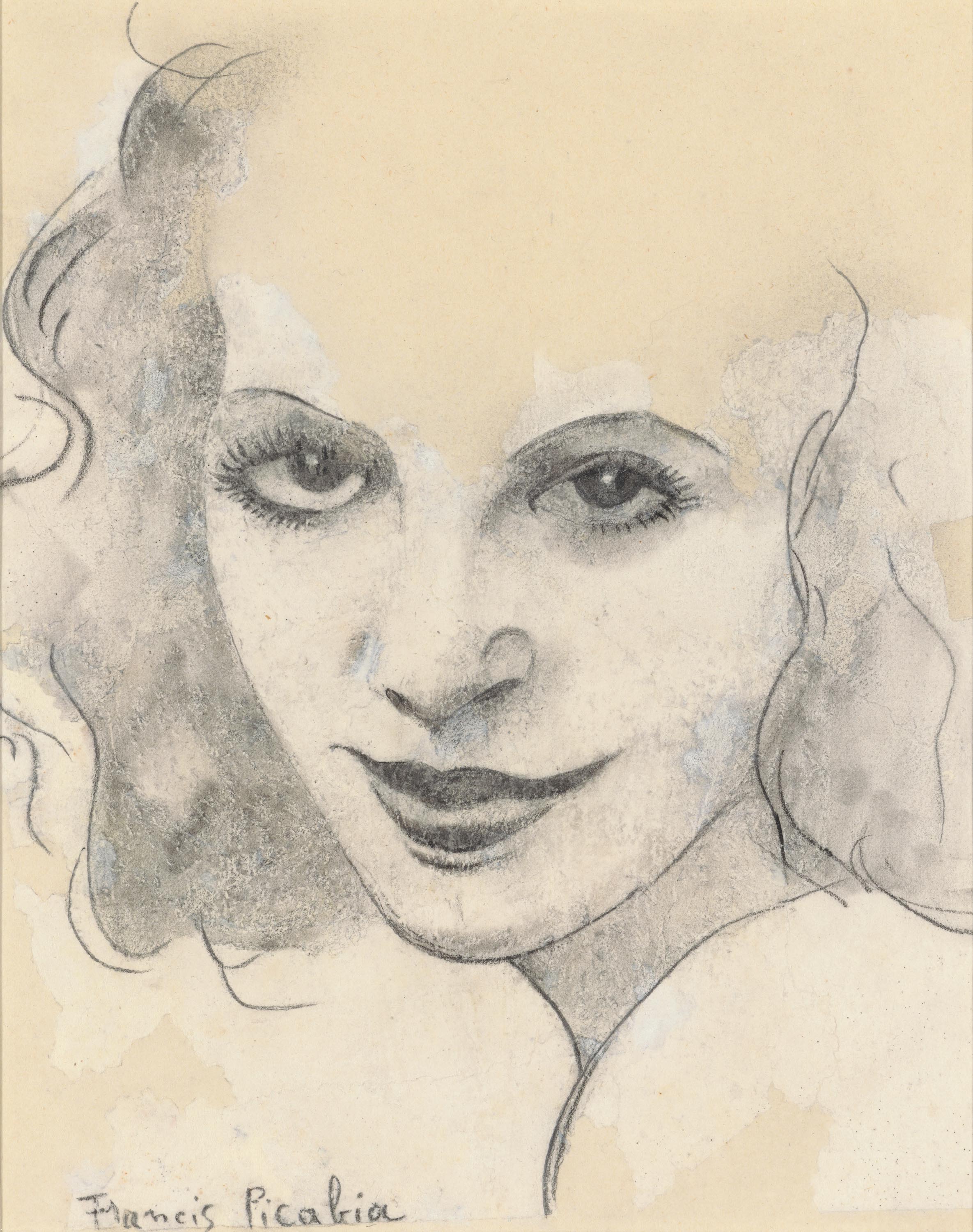

Francis Picabia “Tête de femme”, ca. 1941-1942

As you might expect, several paintings seem to resemble Charlotte Brontë like those by Celia Paul and Gwen John. Elsewhere, portraits by Winold Reiss and Picabia take a different approach, offering Art Deco-inflected visions of the New Woman: stylish, self-possessed, and alert to the possibilities of modern life. Rhys, with her restless intellect and defiance of convention, was most certainly among them.

Although she spent most of her life in relative exile, drifting between Parisian hotels and bleak English lodgings, Dominica remained the wellspring of Rhys’ imagination throughout her career. A modernist of the margins, her work spoke to the dislocated and the overlooked, offering – in sparing, unsentimental prose – a view into lives and cultures largely ignored by European male writers.

It was precisely this attentiveness, Als suggests, that made Rhys fertile ground for a visual dialogue. ‘Because to work with [Michael Werner Gallery’s] roster of stars is like plunging one’s hands into mounds and mounds of delicious gold, rich in intellectual and sensual nutrients that, here, not only spoke to Rhys, but about her and the visual artist simultaneously,’ he says. ‘[It’s] a collaboration that happens when you open your mind to the possibilities of language and the visual working in tandem, not “just” in support of one another.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jean Rhys at Michael Werner Gallery in London runs until 22 November

Florian Krewer “Untitled”, 2021

Katie Tobin is a culture writer and a PhD candidate in English at the University in Durham. She is also a former lecturer in English and Philosophy.

-

These Guadalajara architects mix modernism with traditional local materials and craft

These Guadalajara architects mix modernism with traditional local materials and craftGuadalajara architects Laura Barba and Luis Aurelio of Barbapiña Arquitectos design drawing on the past to imagine the future

-

Robert Therrien's largest-ever museum show in Los Angeles is enduringly appealing

Robert Therrien's largest-ever museum show in Los Angeles is enduringly appealing'This is a Story' at The Broad unites 120 of Robert Therrien's sculptures, paintings and works on paper

-

The Wallpaper* style team recall their personal style moments of 2025

The Wallpaper* style team recall their personal style moments of 2025In a landmark year for fashion, the Wallpaper* style editors found joy in the new – from Matthieu Blazy’s Chanel debut to a clean slate at Jil Sander

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week'Tis the season for eating and drinking, and the Wallpaper* team embraced it wholeheartedly this week. Elsewhere: the best spot in Milan for clothing repairs and outdoor swimming in December

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekFar from slowing down for the festive season, the Wallpaper* team is in full swing, hopping from events to openings this week. Sometimes work can feel like play – and we also had time for some festive cocktails and cinematic releases

-

The Barbican is undergoing a huge revamp. Here’s what we know

The Barbican is undergoing a huge revamp. Here’s what we knowThe Barbican Centre is set to close in June 2028 for a year as part of a huge restoration plan to future-proof the brutalist Grade II-listed site

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s wet, windy and wintry and, this week, the Wallpaper* team craved moments of escape. We found it in memories of the Mediterranean, flavours of Mexico, and immersions in the worlds of music and art

-

Each mundane object tells a story at Pace’s tribute to the everyday

Each mundane object tells a story at Pace’s tribute to the everydayIn a group exhibition, ‘Monument to the Unimportant’, artists give the seemingly insignificant – from discarded clothes to weeds in cracks – a longer look

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThis week, the Wallpaper* team had its finger on the pulse of architecture, interiors and fashion – while also scooping the latest on the Radiohead reunion and London’s buzziest pizza

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s been a week of escapism: daydreams of Ghana sparked by lively local projects, glimpses of Tokyo on nostalgic film rolls, and a charming foray into the heart of Christmas as the festive season kicks off in earnest

-

Wes Anderson at the Design Museum celebrates an obsessive attention to detail

Wes Anderson at the Design Museum celebrates an obsessive attention to detail‘Wes Anderson: The Archives’ pays tribute to the American film director’s career – expect props and puppets aplenty in this comprehensive London retrospective