‘Beyond the Bassline’: 500 years of Black music in Britain

Music is the touchpaper for this superb social-history exhibition at the British Library, London

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

If you’re delving into half a millennia’s worth of cultural research, then you’re really going to need some help. And that’s how ‘Beyond the Bassline: 500 Years of Black British Music’ has become a major exhibition at The British Library in London. ‘At first, people kept asking, ‘Why is the library telling the story?’, admits exhibition curator and public historian Dr Aleema Gray. ‘Of course, it is a place of quiet, but the British Library has an incredible sound archive, too, and so that's where we started.'

Celebrating 500 years of Black British music

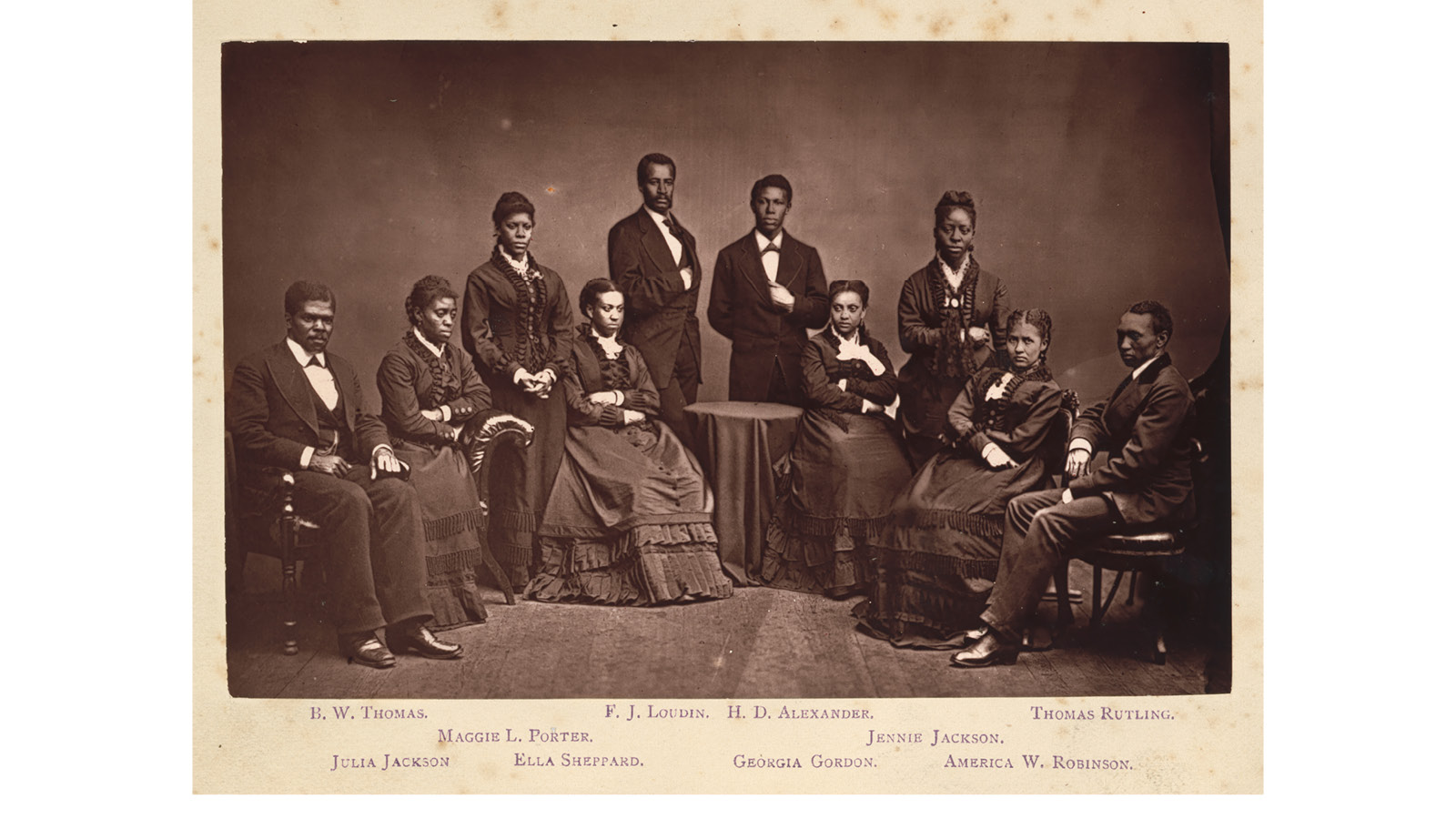

The Black choir, Fisk Jubilee Singers, photographed in 1875

Bringing a noisy idea into a haven of silence, then, is exactly the point, because ‘Beyond the Bassline’ is more than music – the British Library offers over six million sounds in its aural archive, much of it bursting with human expression, from poems and local retellings to random opinions and rare records. It's like a junk shop of noises, packed full of multiple voices and perspectives. ‘Beyond the Bassline’ is a social history with Black British music as its touchpaper. It unfolds through 200 illustrations, including audio-visuals, manuscripts, stage looks, sound systems, Sony Walkmans, photography and Beethoven’s tuning fork. More of which later.

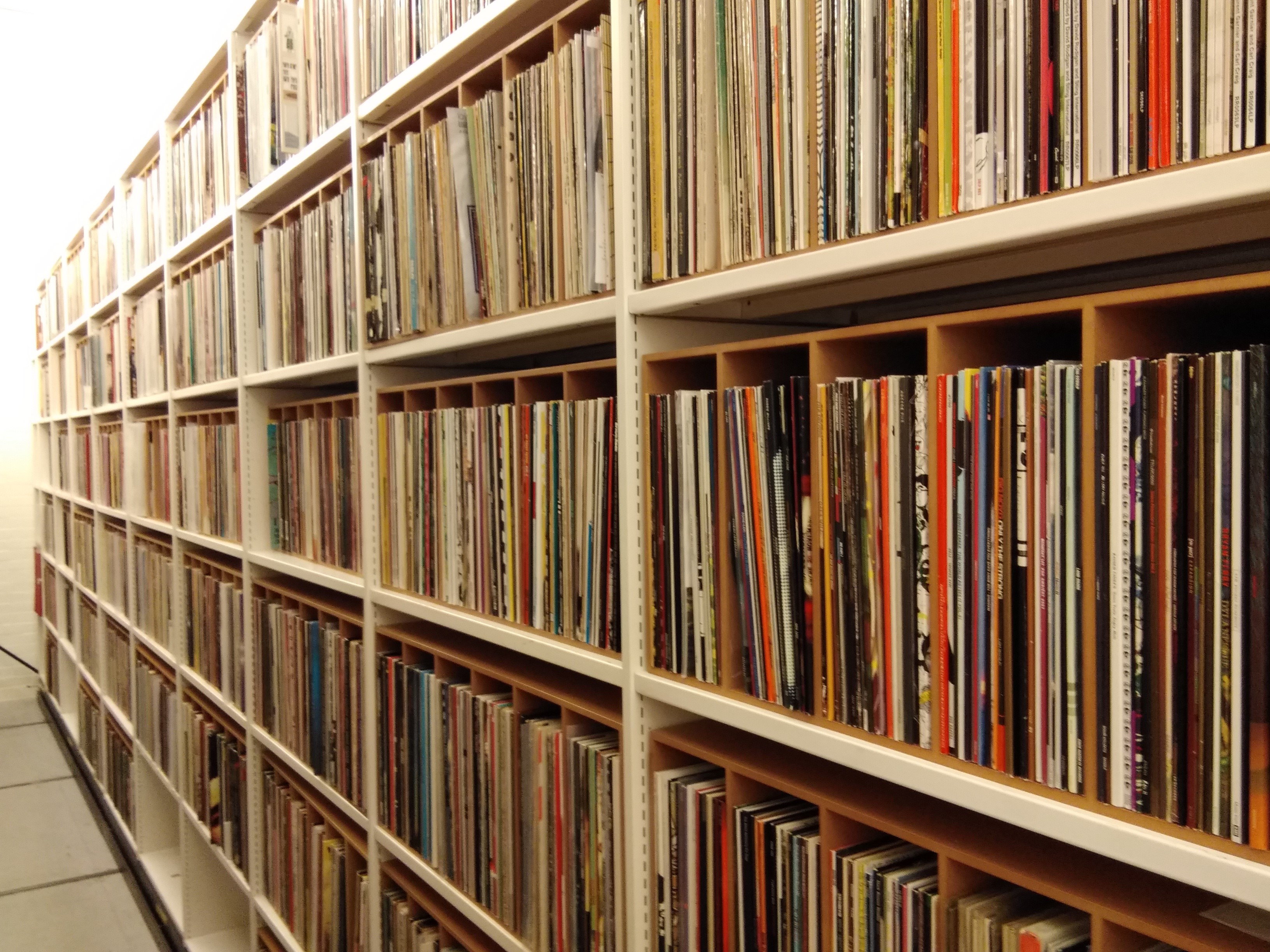

Inside the British Library sound archive

Designed by east London architects, Freehaus, the exhibition, created in partnership with the University of Westminster, is a coruscating journey of African and Caribbean music, creatives and entrepreneurs across Britain, from the 16th century to today. It starts with John Dee’s 1577 map Brytannicæ Republicæ Synopsis (Summary of the Commonwealth of Britain), presented to Elizabeth I, spurring notions of an expansive English navy and empirical pursuits.

Where style and sounds merge

‘The music, the culture we are celebrating took place because of a broader transatlantic exchange, one that is in conversation with colonialism and empire, but that has also brought so many people to this space,’ Gray points out. 'Also, we tend to look towards America when thinking about popular Black music, because it has dominated pop music and a lot of our ideas around Black culture. It was interesting to see a map of our own story emerge through this journey – lovers’ rock, jungle, garage, grime – Black British music genres that were fostered and created in Britain.' (Coincidentally, London’s V&A East is also set to celebrate this legacy with its inaugural show in 2025, ‘Music is Black: A British Story’.)

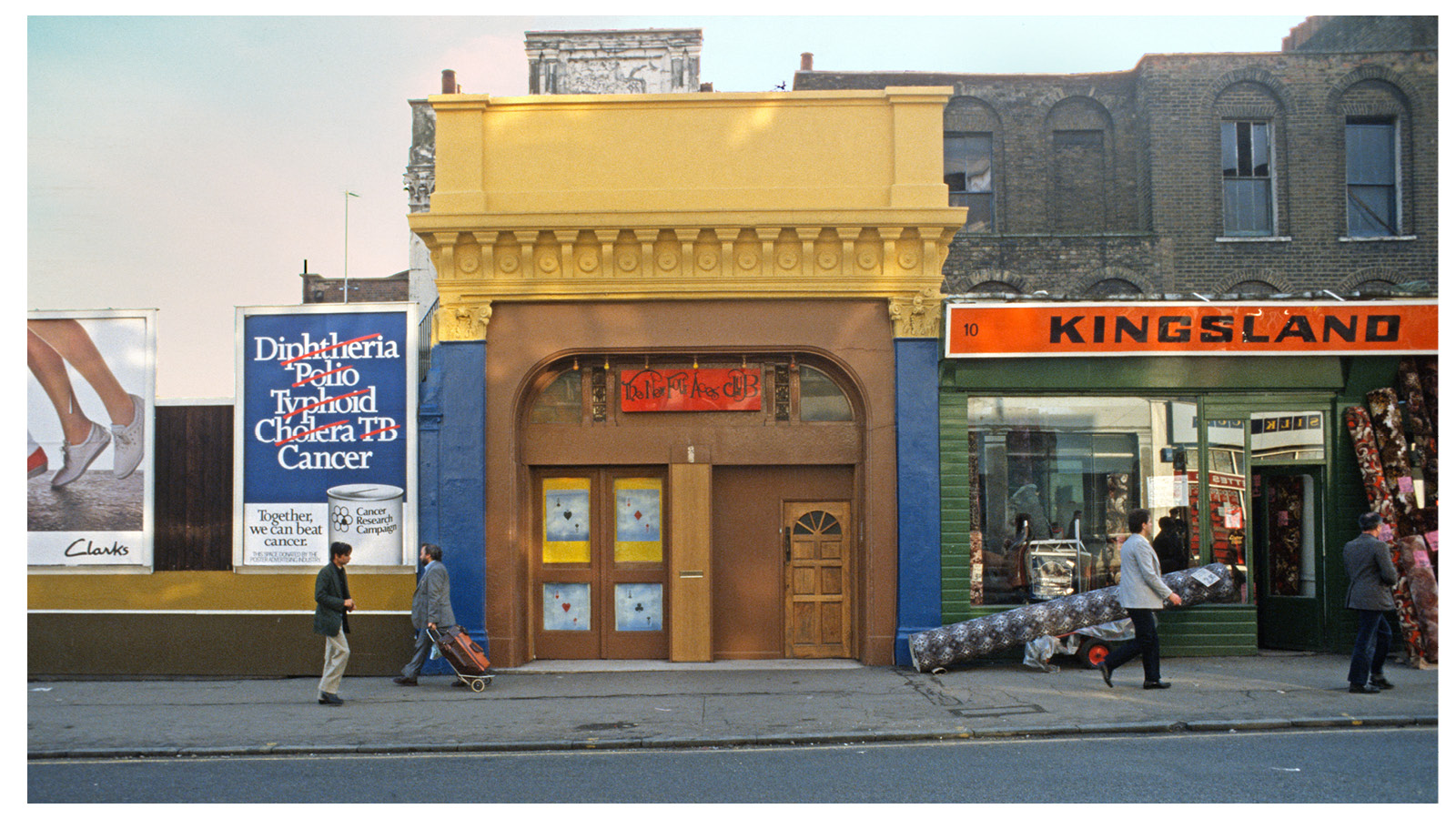

The legendary Black music venue, The Four Aces club, in east London

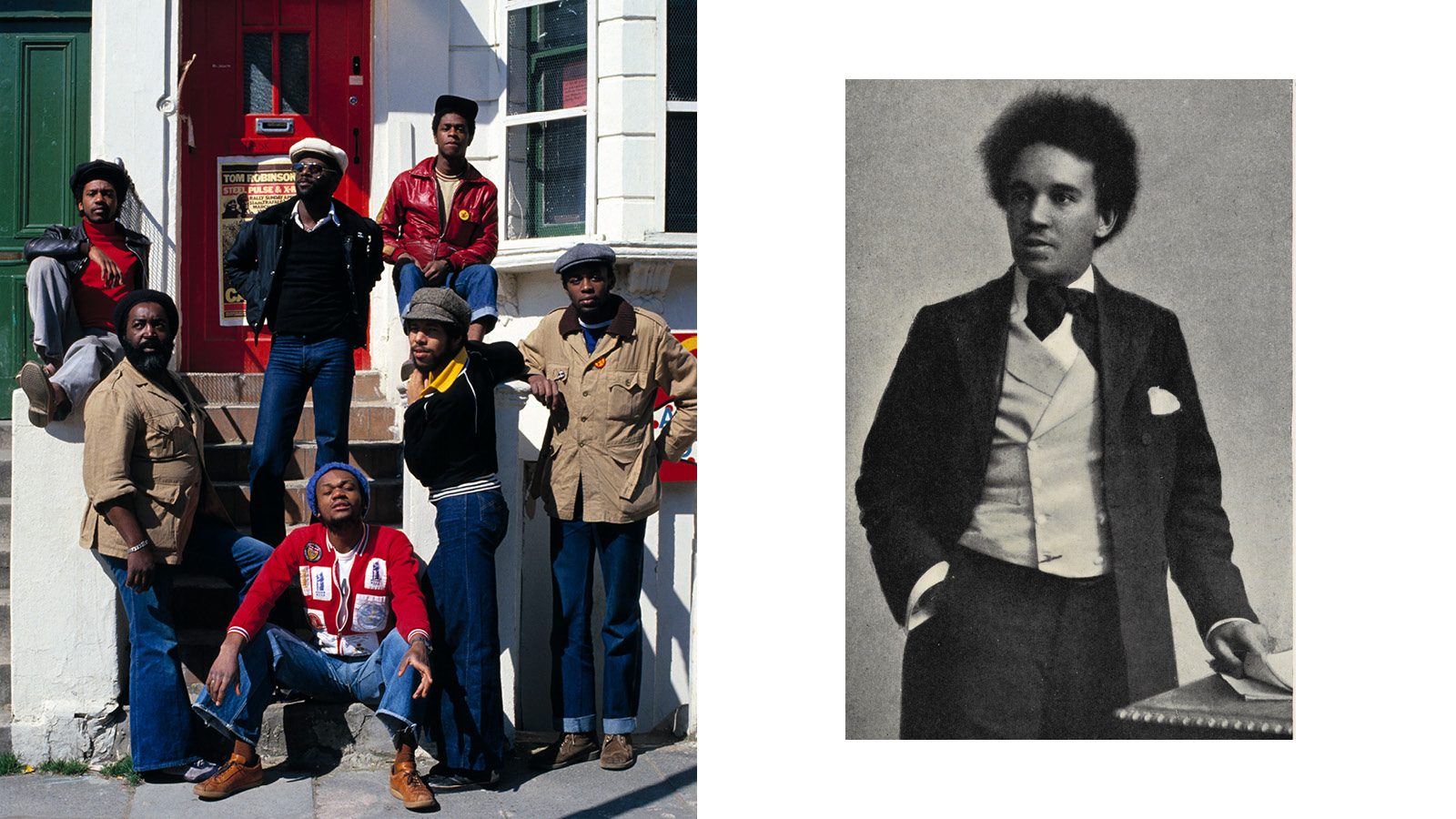

Star names feature, of course – Bob Marley , Stormzy, Soul II Soul, Joan Armatrading, Shirley Bassey, and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor among them. But while they form a recognisable outline, ‘Beyond the Bassline’ doesn’t just stick to the big names or the big city. It illuminates the social scenes that bubble up around music, rummaging around treasured memorabilia from venues such as the 1970s Dundee social, the Reggae Klub, Manchester’s Reno funk and soul club, and the jazz clubs of London’s Soho. Arguably, it’s an homage to communities – the people, spaces and genres that influenced the landscape of Black British music.

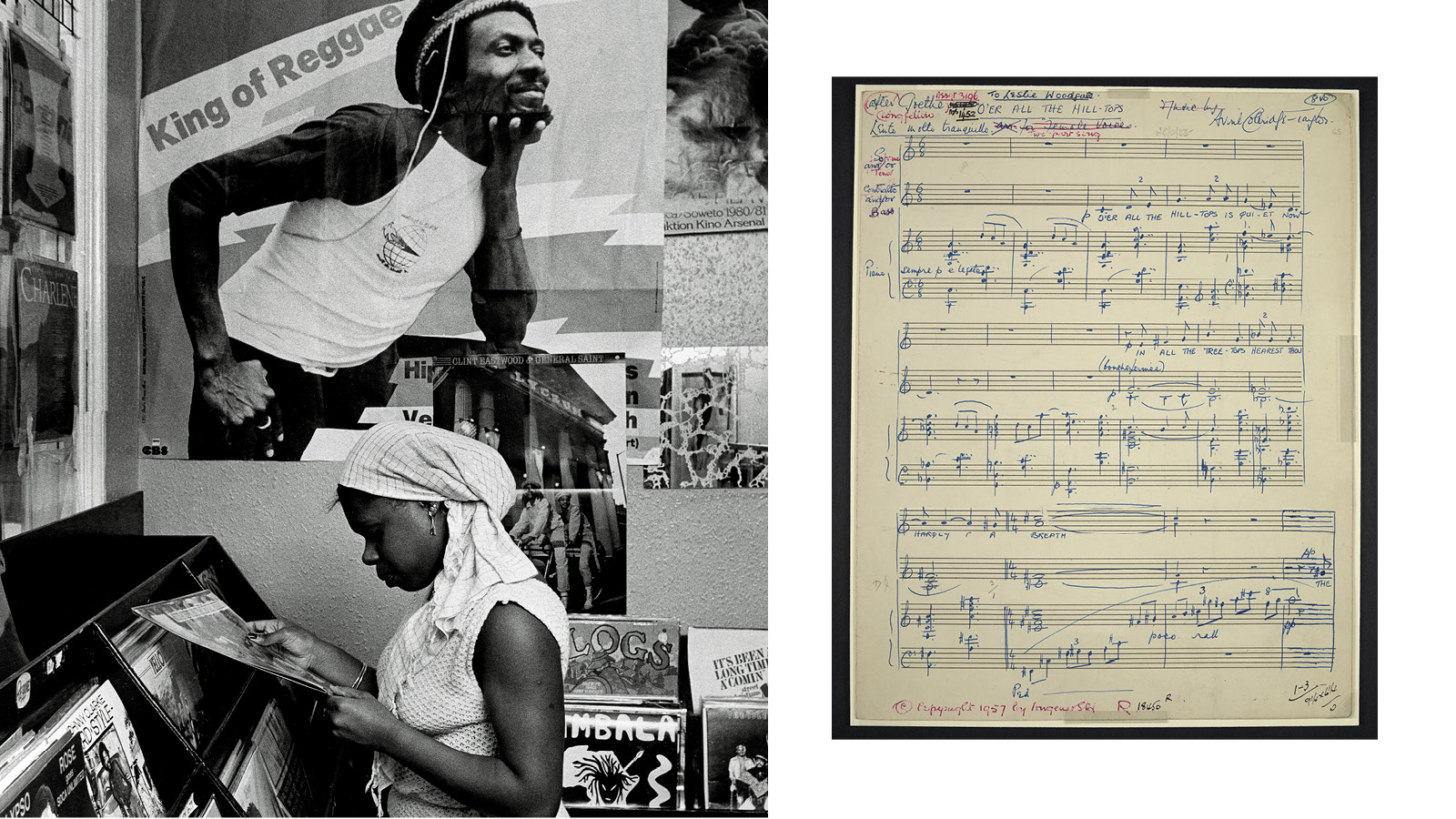

Coventry Ska outfit The Selecter, with singer Pauline Black at the centre

The photography is worth the visit alone, as the exhibition surreptitiously highlights a naturally emerging British photography style in the late 1970s and 1980s, a time when personal cameras had become affordable, and a laissez-faire approach to documenting the everyday was often a natural reaction as opposed to a creative pursuit. Club poster designs, T-shirts and record-sleeve art reveal a similarly ad hoc British style, while The Selecter’s Pauline Black’s trademark trilby is just one of the contributions underlining an associated fashion trajectory. There are paintings by, among others, Jamaica-born, British-based artist and book illustrator Errol Lloyd, while other visual contributions include a specially commissioned short film and sound installation by Tayo Rapoport and Rohan Ayinde in collaboration with the south London-based musical movement Touching Bass.

Left, Birmingham Roots Reggae band Steel Pulse in 1978. Right, Portrait of 19th-century composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

The show is Freehaus’ first exhibition design, and a story spanning 500 years is a weighty brief. But their production is beautifully inventive, using light, texture, colour and unexpected viewpoints with a lightness of touch that does not impinge on the subject, but rather joins in. ‘This is a big story and Freehaus presented a design that was flexible, meaningful, sensitive, considered and completely in line with our curatorial vision,’ says Gray.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

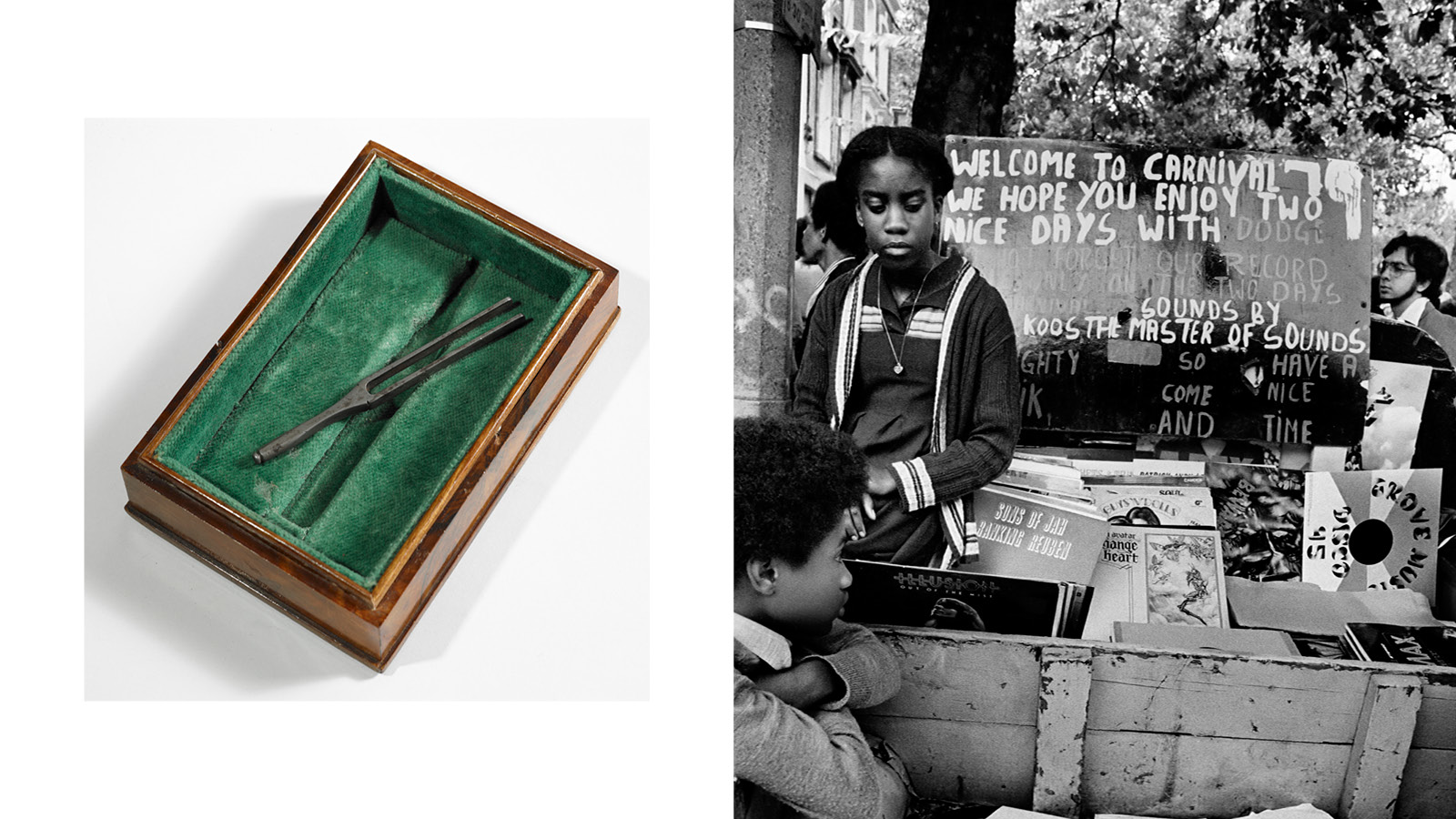

Left, Beethoven's tuning fork, lent to Black violinist George Bridgetower for his performance at the court of George IV. Right, Notting Hill carnival, London

And what about that tuning fork? ‘Everyone is obsessed with Beethoven’s tuning fork,’ says Gray, smiling. ‘Beethoven lent it to George Bridgetower, a super-talented violinist and composer, who took part in a series of concerts that so impressed King George IV, he sponsored the musician’s education.’ The life of John Blanke, the African trumpeter at Henry VIII’s court is also highlighted. ‘That’s what makes “Beyond the Bassline” so interesting,' concludes the show curator. 'It really disrupts a lot of our ideas around Black music and musicians. Music breaks boundaries, but it also inspires activism, identity, fashion and style.’

Left, perusing records while Jimmy Cliff looks on, in 1983. Right, a 1917 handwritten score by Avril Coleridge-Taylor, daughter of composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

‘Beyond the Bassline: 500 Years of British Black Music’, at the British Library until 26 August 2024, is accompanied by a programme of public events, including live performances, club takeovers and in-conversations with singer-songwriters. Beyond the Bassline

Caragh McKay is a contributing editor at Wallpaper* and was watches & jewellery director at the magazine between 2011 and 2019. Caragh’s current remit is cross-cultural and her recent stories include the curious tale of how Muhammad Ali met his poetic match in Robert Burns and how a Martin Scorsese Martin film revived a forgotten Osage art.