Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Windowless walls, made of zigzagging aluminium panels; an impossibly sleek kitchen consisting of repeating geometric units, inspired by the work of Donald Judd; a custom ring-shaped conference table, with a slender marble top and tubular stainless steel supports that bend outwards to offer limited seating. These are some of the defining features of Elmgreen & Dragset’s latest fictional home, installed in Nord gallery of Milan’s Fondazione Prada. Over the years, inspired by the ways in which domestic spaces can express our identities and desires, the Berlin-based artists have created many detailed installations that evoke the lives of imaginary inhabitants – art collector Mr B, whose corpse lay adrift in the pool outside their Venice Pavilion; the elderly architect Norman Swann, disillusioned by professional failures and soon to be evicted from his grand apartment at the V&A; an unnamed family that has just emigrated from the UK back to Germany in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, taking up residence at the Mies van der Rohe-designed Haus Lange. In comparison, the fictional owner of the Fondazione Prada home is even more eccentric and elusive. His belongings suggest enormous wealth and power, but also considerable paranoia.

This point is driven home by a vitrine that houses four artworks: a pair of shrouded heads locked in a kiss, a miniature easel with a peephole that reveals an eye, an egg-shaped silver vessel intended as a resting place for a pair of smartphones (created for Wallpaper* Handmade X), all by Elmgreen & Dragset; plus a black leather-clad bust by Nancy Grossman with an open zipper around its facial features. Our protagonist has shut these symbols of desire behind glass, in the same way he has turned away from the real world and sealed himself in a hermetic bubble.

Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale. La fine di Dio, 1963, hangs above Elmgreen & Dragset’s conference table in marble and tubular steel.

Black, 1973-74, a bust by Nancy Grossman, sits next to Elmgreen & Dragset’s The Bed, 2019, an egg-shaped silver stand for a pair of smartphones created for Wallpaper* Handmade X; Looking Back, 2022, a miniature easel with a peephole, and Untitled (After the Lovers), 2015, a pair of shrouded heads locked in a kiss.

And as the furniture reveals, this is no bubble of comfort. There’s a custom artificial leather bench with a side profile that resembles a cardiogram, and a tempered glass lounger by Konstantin Grcic with a backrest precariously supported by a gas piston. ‘It’s probably the most impossible chair ever designed, and therefore we love it,’ pronounces Michael Elmgreen, as we walk around the freshly installed home in late January. ‘It’s a comment on people arranging their domestic space into more of a showroom than a place for recreation and comfort. We’ve done this to the extreme here – everything is extremely uncomfortable, but it looks really good. Because if we continue to go down our current path in the way we organise our homes, this is what we’ll end up with very soon.’

This minimalist home is part of the artist duo’s new exhibition, ‘Useless Bodies?’, one of the most ambitious thematic investigations realised by the Fondazione Prada to date. As the title suggests, it ponders on the marginalisation of the body in the post-industrial age. Our homes are optimised to serve as social media backdrops, rather than to provide physical refuge; we are reduced to data points to feed the beast of Big Tech. We see this on a digital screen within the home that displays various statistics about our protagonist – his heart rate, stress levels, number of likes accumulated on social media; ‘all these things that have to do with our narcissistic perception of being perfect bodies’, says Elmgreen.

I don’t know if this home resembles a bomb shelter or a spaceship. But for the rich, it will of course be one or the other in the future.

These statistics overlay an image of Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo’s Il Quatro Stato, 1901, one of the earliest paintings ever made of a worker’s strike and a clarion call against extractive capitalism. Its dignified portrayal of working-class protesters suggested an inexorable march towards a more equal society – a promise largely unfulfilled. Corroborating this sense of disappointed hope, an easel props up architectural plans for what appears to be a combination of an art museum, free port, and panopticon prison, a reminder that the trappings of civilisation are often enabled by prerogatives of the wealthy and the exploitation of the poor.

‘I don’t know if this home resembles a bomb shelter or a spaceship,’ remarks Dragset. ‘But for the rich, it will of course be one or the other in the future.’

Elmgreen & Dragset have transformed the Nord gallery at Fondazione Prada into an unliveable home of extreme vanity, with details such as rows of mortuary drawers; seating with a profile shaped like a cardiogram, and a Unitree A1 robot dog, programmed to walk around the home and wiggle, offering visitors a dash of dark humour. On the wall is Circulation, 2019.

Apart from a Unitree A1 robot dog (which is programmed to walk around the home and wiggle, offering visitors a dash of dark humour), there is no sign of activity within the 585 sq m home. As we approach the exit, we see the pièce de résistance – a grid of steel mortuary drawers, one of them left open with a pair of pale male feet jutting out, presumably belonging to our protagonist. It’s meant to be at once disconcerting and reassuring. ‘This is the only real democratic thing in our whole way of living,’ Elmgreen explains.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

It doesn’t really matter how rich or powerful you are, this is what you’ll look like in the end.

Untitled, 2011, a set of mortuary drawers with a single silicone corpse, is the final artwork that viewers encounter in the fictional home that Elmgreen & Dragset have created for the Nord gallery at Fondazione Prada.

While the home in the Nord gallery presents a near-future vision of a one-percenter’s lair, another installation, occupying the upper level of the Rem Koolhaas-designed Podium building next door, shows the engine room of plutocracy. Aluminium foam walls and fluorescent strip lighting lend the space a corporate, clinical atmosphere, which inspired the artists to transform it into a contemporary office. On one end is a 2006 piece, It’s The Small Things in Life That Really Matter, Blah, Blah, Blah. Initially conceived for their seminal ‘Welfare Show’ at Serpentine Gallery, it comprises a number dispenser, an electronic number display, a row of seats and other accoutrements commonly found in a waiting area.

On the other end, the artists have crammed in a mammoth new work, Garden of Eden, 2021, comprising 35 office cubicles (each offering workspace for two) neatly arranged into seven rows. There are computers, desk chairs, as well as small personal items that evoke the lives of individual workers: here’s a kitschy gadget, there’s a postcard from a family holiday to Tenerife, reflecting the desire to shape one’s environment however soulless the corporate workspace may be. It calls to mind the artists’ 2010 installation The One & the Many, a four-storey housing block within the ZKM Museum of Contemporary Art in Karlsruhe that offered brief glimpses of its tenants’ lives – here, grey Maharam fabric partitions have replaced prefabricated concrete, but the weight of conformity continues to loom heavy.

A detail of Doubt, 2019, which features a polished stainless steel mirror with irregular holes that seem to have been created by a hand poking through its surface

As with the Nord gallery, there are no inhabitants in sight. The office looks as if it has been hastily abandoned, calling to mind Covid-era lockdowns, but the artists in fact conceived Garden of Eden long before. It was intended as a comment on the throttling effects of capitalism, and the constant need to optimise space (workers are squeezed into tighter and tighter quarters, so employers can get more bang for their buck), though in light of recent events, it can also be read as a memorial to times past.

‘We can perhaps say, we won’t miss this office set-up, because it wasn’t optimal to work in that way,’ reflects Dragset. ‘But on the other hand, it’s a sad memorial because we’ve lost our togetherness, the social dimension of being in a workspace together.’

Proving his point, a readymade water cooler stands nearby, filled with water from Flint, Michigan, where ongoing lead contamination became a symbol of inequality and political failure. After years of clean-up, the city’s water was scientifically proven to be potable in 2019, but its notoriety lingers, so the artwork title Flint Water is enough to give us pause. It also raises the question of how the experience of the Covid pandemic may have lasting damage on our psyche, to an extent that we can never look at the gathering of our physical bodies in the same way again.

Elmgreen & Dragset, Watching, 2017. Collection of Lora Reynolds and Quincy Lee, Austin.

A post shared by Elmgreen & Dragset (@elmgreenanddragsetstudio)

A photo posted by on

One floor down, the artists have gathered physical bodies nonetheless, only in the form of sculpture. Here, iconic works such as He (Silver), 2013 (a male version of the famous Little Mermaid statue on Copenhagen’s waterfront), and For today I am a child, 2016 (a boy gazing at a rifle that has been encased in a glass vitrine, a vision of a world beyond gun violence) intermingle with more recent pieces, many produced during the Covid pandemic. Notably, a boy on an umpire’s chair (Watching, 2021) highlights the ways in which we have been relegated to observers rather than participants in society, and a pair of young boys wearing VR goggles (This is How We Play Together, 2021) bemoans the toll of digital technologies. They are placed in dialogue with older sculptures, from Greco-Roman to Bertel Thorvaldsen and Luigi Secchi, that defy conventional representations of heroism and masculinity. The duo selected these pieces in response to Fondazione Prada’s inaugural show in 2015, which emphasised triumphant portrayals of idealised bodies within classical sculpture.

‘The more we looked, we saw that there are quite a lot of links between the Greco-Roman tradition and our sculptures, that even we ourselves weren’t aware of,’ says Elmgreen. ‘Classical and neoclassical sculpture is in fact rich in representations of normal citizens, more body types and more effeminate postures.’ To highlight the contemporary relevance of these representations, the artists have developed a system of cross-references, juxtaposing these pieces with their own work and positioning the sculptures in unusual ways – for instance, an athlete appears to be hiding within a metal frame rather than using it as a pedestal.

Elmgreen & Dragset, This is How We Play Together, 2021. Christen Sveaas Art Collection.

Elmgreen & Dragset,The Outsiders (installation view, Unlimited, Art Basel, Basel, 2021), 2020. courtesy of Pace Gallery, New York

Positioning and recontextualising are integral to the practice of Elmgreen & Dragset, who once set up a Prada store in the middle of the desert (Prada Marfa, 2005, is a pilgrimage spot for art lovers and remains one of the artists’ best-known works). On the grounds of the Fondazione Prada, near the entrance to Restaurant Torre, they’ve installed The Outsiders, 2020, depicting two male art handlers made out of silicone, snuggled up against each other among packed artworks in the back of a Mercedes-Benz W123 wagon from the 1970s. Originally envisioned for Art Basel, it is a reminder of the unacknowledged and often deliberately hidden human labour behind the art world’s pristine façade.

The final part of the show takes up the Cisterna, a trio of spaces that contained enormous cisterns back when the Fondazione Prada had been a gin distillery. The artists have transformed these into a forsaken spa, with a locker room on one end and an abandoned pool on the other. In the former, some of the locker doors are left ajar, revealing objects that once again invite us to imagine the personalities and lifestyles of their owners. In one of them, a pair of briefs is suspended on a hook, underneath it is a pair of white flip-flops, neatly arranged as though on a shop floor; in another, an FFP2 mask and a pack of aspirin. A particularly messy locker reveals a small heap of rumpled clothing, a full ashtray, and a used espresso cup atop a torn packet of sugar. There’s also an empty locker with its interior entirely clad in 24-carat gold leaf, a reference to OMA’s gold cladding for the Haunted House at Fondazione Prada.

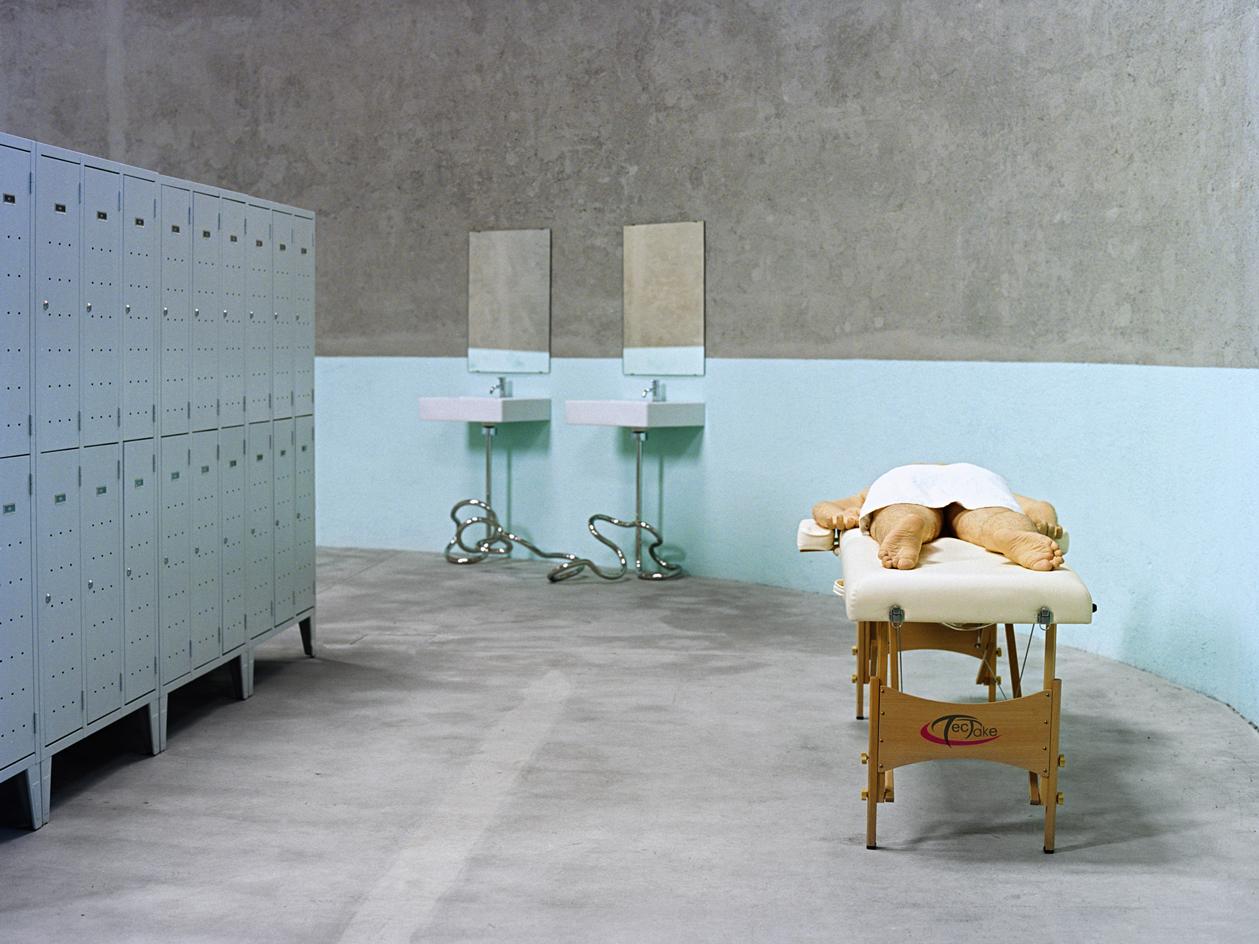

In the Fondazione Prada exhibition, a locker room features Marriage, 2004, two sinks connected with a twisting pipe and The Touch, 2011, a life-size silicone figure of a naked man on a massage table. Some of the locker doors open to reveal their fictional owners’ personal effects, such as a heap of clothing, a full ashtray and a used coffee cup.

Further spa and changing room-related sculptures populate the space, including a massage bench where a life-size silicone figure of a naked man lies prone, covered only by a white towel over his hips. Despite its title, The Touch, 2011 does not include the figure of a masseur, giving the impression of eternal purgatory. Alongside, we see a pair of sinks connected with a twisting pipe, a pair of wooden doors linked with a security chain that would prohibit either from fully opening, and two pairs of rumpled jeans and some underwear that seem to have been recklessly discarded in a steamy rendezvous. Meanwhile, the empty pool, reminiscent of the artists’ installation at Whitechapel Gallery in 2018, is littered with debris and incongruously adorned with a bronze car seat, and a lacquered aluminium rock on a trampoline.

Elmgreen & Dragset's Powerless Structures, Fig. 137, 2015, featuring a pair of wooden doors connected with a security chain that prevents them from opening.

The space in the middle is also the last one visitors see as they exit the exhibition, and it’s empty at ground level – we have to look up to discover the final artwork, What’s Left, 2021, showing a young man, clinging on to a wire with his right hand to prevent himself from falling, and clutching a balancing pole in another. With this piece, the artists want us to ponder, ‘should we really try to come up on that wire again and continue? Or should we just give up, loosen the grip and see if we will survive or die?’

Littered with debris, the empty swimming pool in the gallery’s Cisterna is reminiscent of Elmgreen & Dragset’s installation at the Whitechapel Gallery in 2018. The space also features Too Heavy, 2017, a lacquered aluminium rock on a trampoline.

Next to the empty swimming pool is I must make amends, Fig. 2, 2019, a patinated bronze cast of a Mercedes-AMG car seat that references Janis Joplin’s ‘Mercedes Benz’ song, a hymn to anti-capitalism.

Dragset adds that this is a commentary on our physical existence, as well as on political ideology. There’s a 1990s look to the young man’s attire, alluding to the optimism of the West following the fall of the Berlin Wall. But the words ‘What’s Left’ on his T-shirt are the artists’ commentary on how capitalism has failed us. We have been disappointed, but are nonetheless unable to come up with a viable alternative.

It’s a nerve-wracking note on which to end a disquieting exhibition. But don’t call the artists pessimistic. ‘It’s important to note that the show is titled “Useless Bodies?” with a question mark. Our answer, if any, would be no,’ Elmgreen concludes. ‘It’s an exhibition that we hope will encourage viewers to say, we need better spaces for our bodies, we need to put less pressure on our bodily appearances. And we need to be accepted as bodies and not only minds, to remind ourselves of the value of being physical beings.’

Detail of Powerless Structures, Fig. 19, 1998, which features two pairs of crumpled jeans and some underwear that seem to have been discarded in a steamy rendezvous.

Ingar Dragset and Michael Elmgreen with What’s Left, 2021, which shows a young man hanging precariously from a wire. There’s a 1990s look to his attire, alluding to the optimism of the West following the fall of the Berlin Wall, but the words ‘What’s Left’ on his T-shirt are the artists’ commentary on how capitalism has failed us.

INFORMATION

A version of this article will appear in the May 2022 issue of Wallpaper*, on newsstands and available to subscribers from 7 April. Subscribe today

Elmgreen & Dragset, ‘Useless Bodies?’, until 22 August, Fondazione Prada, Milan. fondazioneprada.org; elmgreen-dragset.com

TF Chan is a former editor of Wallpaper* (2020-23), where he was responsible for the monthly print magazine, planning, commissioning, editing and writing long-lead content across all pillars. He also played a leading role in multi-channel editorial franchises, such as Wallpaper’s annual Design Awards, Guest Editor takeovers and Next Generation series. He aims to create world-class, visually-driven content while championing diversity, international representation and social impact. TF joined Wallpaper* as an intern in January 2013, and served as its commissioning editor from 2017-20, winning a 30 under 30 New Talent Award from the Professional Publishers’ Association. Born and raised in Hong Kong, he holds an undergraduate degree in history from Princeton University.