Digital Revolution: the Barbican shows bits and bytes in a new light, from retro gaming to Will.i.am

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

What connects 8-bit computer games, LED-embedded fashion and a twenty-foot tall singing pharaoh? The latter is actually a virtual representation of singer, entrepreneur and digital evangelist Will.i.am, just one of a host of contributors to the Barbican’s sprawling new show, Digital Revolution. We caught up with Will.i.am to talk about his installation, ‘Pyramidi’, and delved into the dense display of computer culture that makes up this fascinating show.

The distinction between creativity and digital creativity is an increasingly arbitrary one, given the almost utter ubiquity of our connected existence. From the outset, Digital Revolution’s curatorial team acknowledge that the virtual realm has been well-travelled in the past - the Barbican's own Serious Games in 1997 and 2002's Game On attempted to bring the imagery and influence of bits and bytes to a wider audience. But Digital Revolution's point of difference is that it's not just about the arts in isolation or the gaming industry, but about the way digital culture permeates every single aspect of modern creative culture, from fashion to pop to art to apps.

The exhibition also marks a key waypoint in the rapid explosion of digital creativity. We now have a culture that dreams up billion dollar apps, new means of interacting, entertaining, tracking and tracing our paths through life, together with an emerging generation that has never known a world without the internet, email and SMS. They can take every evolution or revolution in their stride.

Crammed into a sub-divided and darkened Curve gallery, the first section of the main show is dedicated to 'digital archaeology', and features a host of early computers, consoles, cabinets, machines and multimedia projects, many of which have been literally excavated from the accumulated detritus of the pop culture that followed. Sprites glow, bleeps beep and the overall effect is a dark, brooding retro-futurism, a space of wonder and nostalgia.

Guest curator Conrad Bodman has also devoted sections to the myriad ways in which modern computing can enable us to collaborate and create, as well as the multifarious and splendid realms that emerge from the world's cinema SFX houses. From here it's a short step to literally immersing oneself in a series of digital artworks, many of which have been specially commissioned for Digital Revolution. Just as the touch screen device has transformed the way we react to information, so we are entranced by large scale video displays that pump out instant graphic modifications - adding wings to arms, a swarm of pecking birds, a Boccioni-esque breakdown into a thousand shimmering lines, or a host of other objects and presentations that are part of the ongoing creation of a reactive, hybrid digital world.

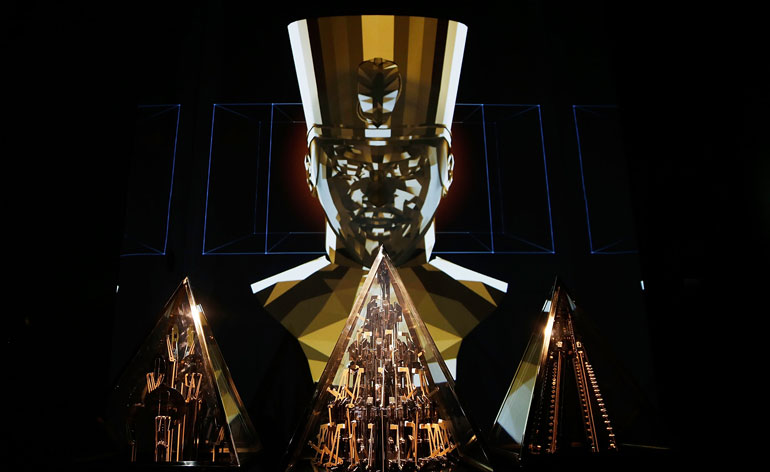

One of the largest installations is the new piece by the musician Will.i.am and the artist Yuri Suzuki. 'Pyramidi' puns on the universal language of computer music, and sets three elaborate 'instruments' alongside a titanic computer-generated animation of Will.i.am singing a new composition, Dreamin' about the future. Thanks to the combination of cutting edge projection mapping and the age-old hollow-face illusion, the Pharaonic visage of Will.i.am genuinely seems to follow you around the room as the music rolls and the three instruments do their stuff.

Digital Revolution is more akin to a mini-festival, one which will evolve and mutate over its two-month run with many immersive exhibits that bring the viewer right into the artwork. Given the wealth of material on display and the sheer depth of some of the generated worlds, the show will repay repeated visits.

We spoke to Will.i.am about his involvement in Digital Revolution and his thoughts on the future of technology and creativity...

W*: How did this come about? Why are you here now at the Barbican?

Will.i.am: They asked if I was interested in collaborating and doing an installation. Yuri and I were already in the process of figuring out how we materialise this concept of robotic instruments. We just married the two roads.

So the pyramids are deconstructed instruments, creating the sounds?

They're playing the songs, playing MIDI. Sérgio Mendes is the star of the show. That Rhodes solo is Sérgio Mendes, played just like he played it the first time - every single time that piano plays it it's exactly the same. It's similar to a player piano. When the player piano was invented, there wasn't a player guitar and a player drummer.

How did you come up with the aesthetic of the video component?

Once we'd figured out the way to do the trio, we were like 'what about vocals?' 'Oh, why don't we do projection mapping - oh yeah.' We were geeking out at the highest level of geekdom.

You basically had access to any way you wanted to do things...

My circle of collaborators is vast, from visual effects to light installations, through to gadgets and doodads and making things and then there's a whole other army of people I can work with.

How do you feel about the rest of the show?

It's awesome to be in this creative company - I couldn't have chosen a better place to have my first installation.

Is there anything in terms of technology that you want to do but are unable to because of limitations? What's the next thing?

You know what's crazy? That there's nothing in the world besides cures for diseases, that you can't manifest with the right collaboration and the right will instilled in the people you're collaborating with. Anything is possible now, for the first time in humanity. It's an amazing time.

Will this kit live on in other performances?

It opens up a whole new platform to compose for. We wanted to take yester-world, the equipment and function of a piano and blend it with the mind of a computer - a true hybrid. I would like to see Kanye West compose for this set-up. Hey Kanye, here's a projector, here are the instruments, drums, keys, guitar and backing synths for sub-bass. Create here.

What do you think this exhibition means and why is it significant?

I remember [Interscope Geffen A&M chairman] Jimmy Iovine had a quote. We were sitting in his office in 2003. The Black Eyed Peas were about to launch iTunes with Hey Mama and everyone was hollering about Napster and the fight between the entertainment industry and Silicon Valley. Jimmy said that 'you know, when the Renaissance stopped, it's not liked people stopped painting.' What we're experiencing right now is the beginning of a new Renaissance. A whole new type of artist is emerging - the makers, the coders. They're artists.

One of the largest installations is a new piece by musician Will.i.am and artist Yuri Suzuki. 'Pyramidi' puns on the universal language of computer music, and sets three elaborate 'instruments' alongside a titanic computer-generated animation of Will.i.am singing a new composition.

Thanks to the combination of cutting edge projection mapping and the age-old hollow-face illusion, the Pharaonic visage of Will.i.am genuinely seems to follow you around the room as the music rolls and the three instruments do their stuff.

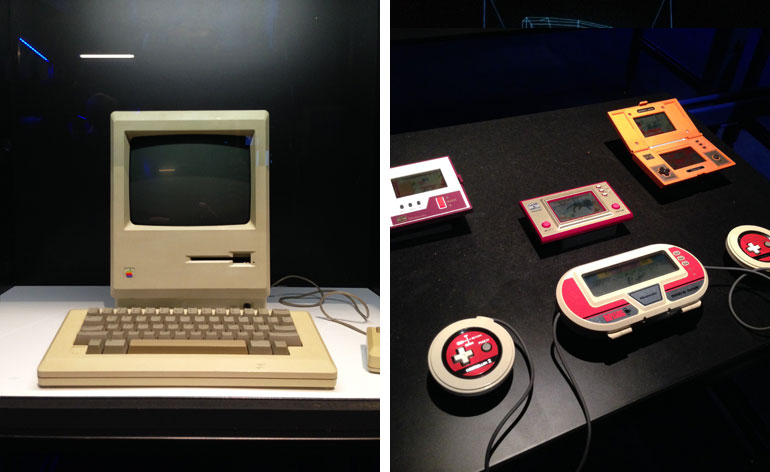

The first section of the main show - crammed into a sub-divided and darkened Curve gallery - is dedicated to 'digital archaeology', and features a host of early computers, consoles, cabinets, machines and multimedia projects.

Many of the artefacts on show have been literally excavated from the accumulated detritus of the pop culture that followed.

Detail of an obsolete Apple Macintosh interface

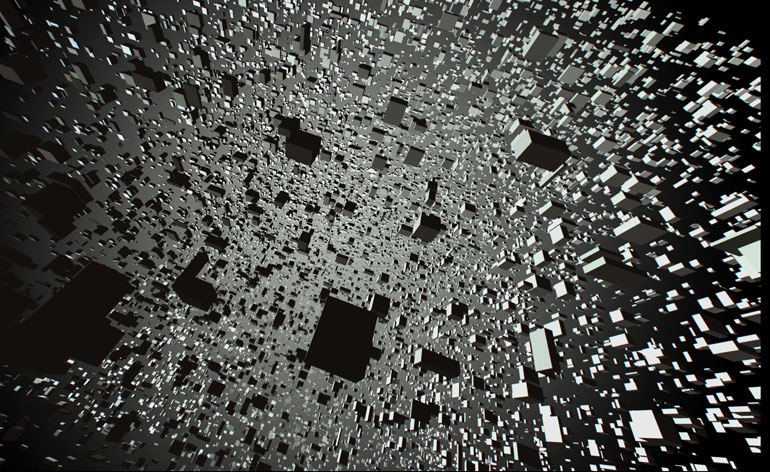

The curator, Conrad Bodman, has also devoted sections to the multifarious and splendid realms that emerge from the world's cinema SFX houses, such as in the recent science fiction thriller Gravity (pictured). The film, which takes place in outer space, contains an unpredecented 80 per cent CG imagery.

In the adjacent installation, Chris Milk experiments with notions of play and gesture, transforming visitors into birds with his striking shadow play work, 'The Treachery of Sanctuary'.

From here it's a short step to literally immersing oneself in a series of interactive digital artworks, which have been specially commissioned by the Barbican and Google for the show's DevArt section, celebrating art made with code.

Visitors are invited to share a spoken wish at the 'Wishing Wall', and watch their words transform into fluttering digital butterlies.

'iMiniSkirt', by fashion technology studio CuteCircuit, is an interactive pleated mini-skirt that animates in colourful patterns, controlled by an iPhone app.

'Wearable Solar', by Pauline van Dongen, 2013. © Mike Nicolaassen

The Barbican's foyer holds court with an interactive installation by Minimaforms, named 'Petting Zoo'. Here, visitors can play with giant pet 'snakes' equipped with sensors that react to movement and touch.

Another work commissioned especially for the show is 'Assemblance' by creative think tank Umbrellium, in the Pit Theatre.

The installation is an atmospheric and unique three-dimensional light field where visitors can collaborate with others to shape, manipulate and interact beams of light.

A still from the 1983 game 'Attack of the Mutant Camels', published and developed by Llamasoft.

'Pixorama', by Eboy

Digital Revolution's point of difference is that it's not just about the arts in isolation or the gaming industry, but about the way digital culture permeates every single aspect of modern creative culture, from fashion to pop to art to apps.

'ISAM', by Amon Tobin, 2011.

'Clouds', by James George and Jonathan Minard, 2013

ADDRESS

Barbican Centre

Silk St

London EC2Y 8DS

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.