The Louvre Abu Dhabi will open this year and curator Jean-Luc Martinez is just a bit terrified

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

My taxi streaks along the Corniche, a black curve of velvet tarmac that looks like a giant apostrophe carved in the desert sand. To the left, the Arabian sea shimmers silver. To the right, the golden skyscrapers of the petrodollar plutocrats soar above the minarets of the mosques. Mammon and God jostle for supremacy in the world’s richest oil city.

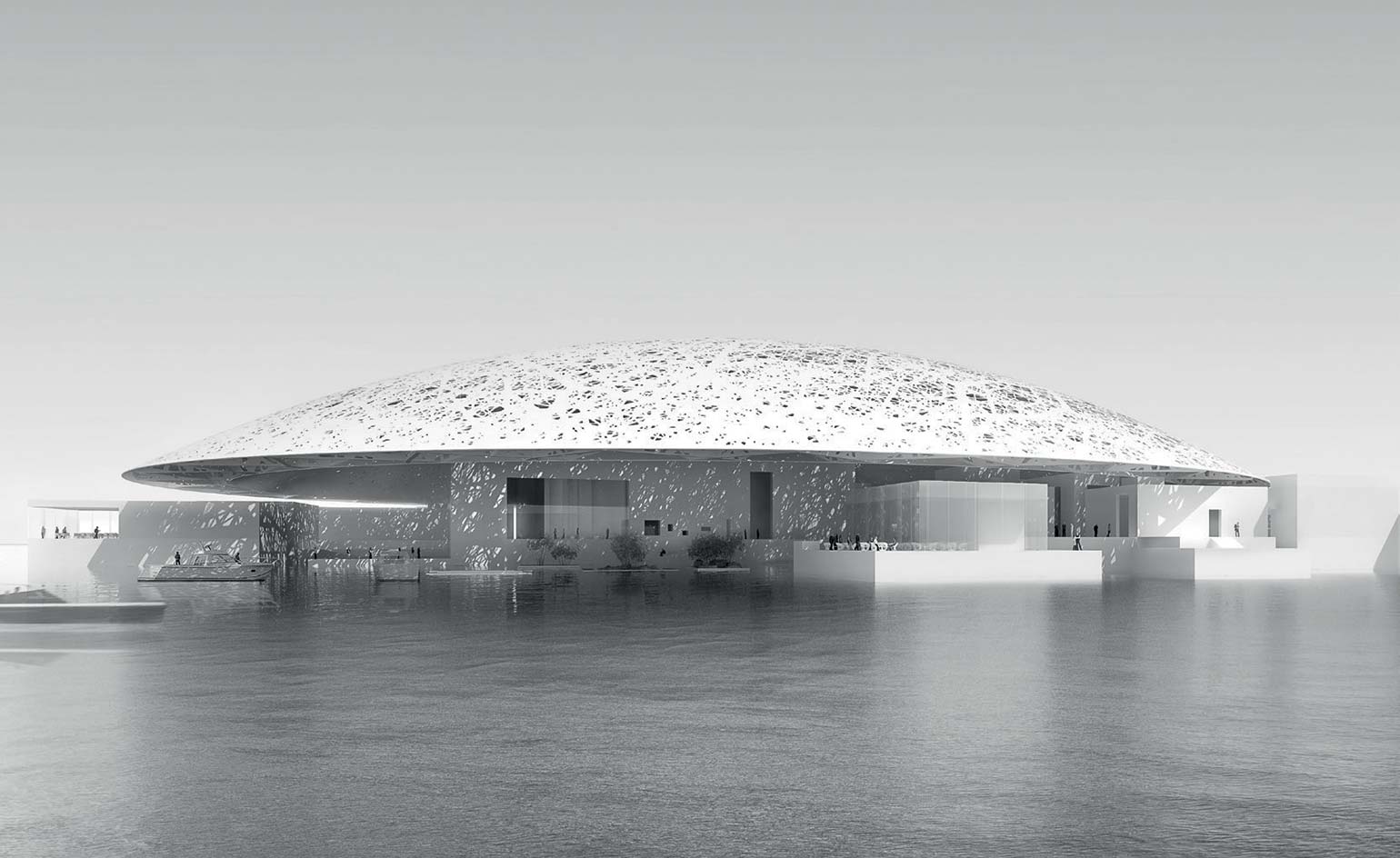

Just past the dhow-lined Port Zayed, the road rises on to Sheikh Khalifa Bridge, which leads to Saadiyat Island, a triangular sandbar off the coast of downtown Abu Dhabi. And that’s when you see it – the most striking new art gallery and the best new building in the Middle East, if not the world.

The 600ft-wide sun-bleached concrete dome of the Louvre Abu Dhabi may weigh 12,000 tonnes, almost double the weight of the Eiffel Tower, but from a distance it seems to float in the soupy desert air. The tops of the four vast pillars that support it are hidden from view. The dome is perforated with a complex geometric pattern of stars, repeated at various sizes and angles in different layers, creating a delicate, lace-like surface. Rays of sunlight dart through the gaps, falling like golden rain into the traditional falaj-style canals that flow between the 12 permanent galleries below.

For now, the heavily guarded perimeter fence is the closest anyone except the building’s architect, Jean Nouvel, plus his benefactors, the ruling Al-Nahyan family of Abu Dhabi, can get to the new Louvre. But this year that will change. After a five-year delay – caused by the global financial crisis and a more local financial crisis, the collapse in the oil price from more than $100 a barrel to less than $30 – the museum will finally open its doors.

The joint venture between the French government, the Louvre and the Al-Nahyans, who govern one of seven semi-autonomous sheikhdoms that make up the United Arab Emirates, is the biggest bet any modern city or gallery operator has made on the appeal and value of art. The Al-Nahyans have lavished an estimated £3bn on the project, in the hope that it will earn the UAE capital a reputation for culture, not merely carbon, and attract tourists, helping to diversify the local economy. The Louvre is pocketing a record £1bn in fees – almost half of that sum alone for granting Abu Dhabi the right to use the Louvre name for the next 30 years. The rest of the cash meets the cost of the Louvre’s curatorial smarts.

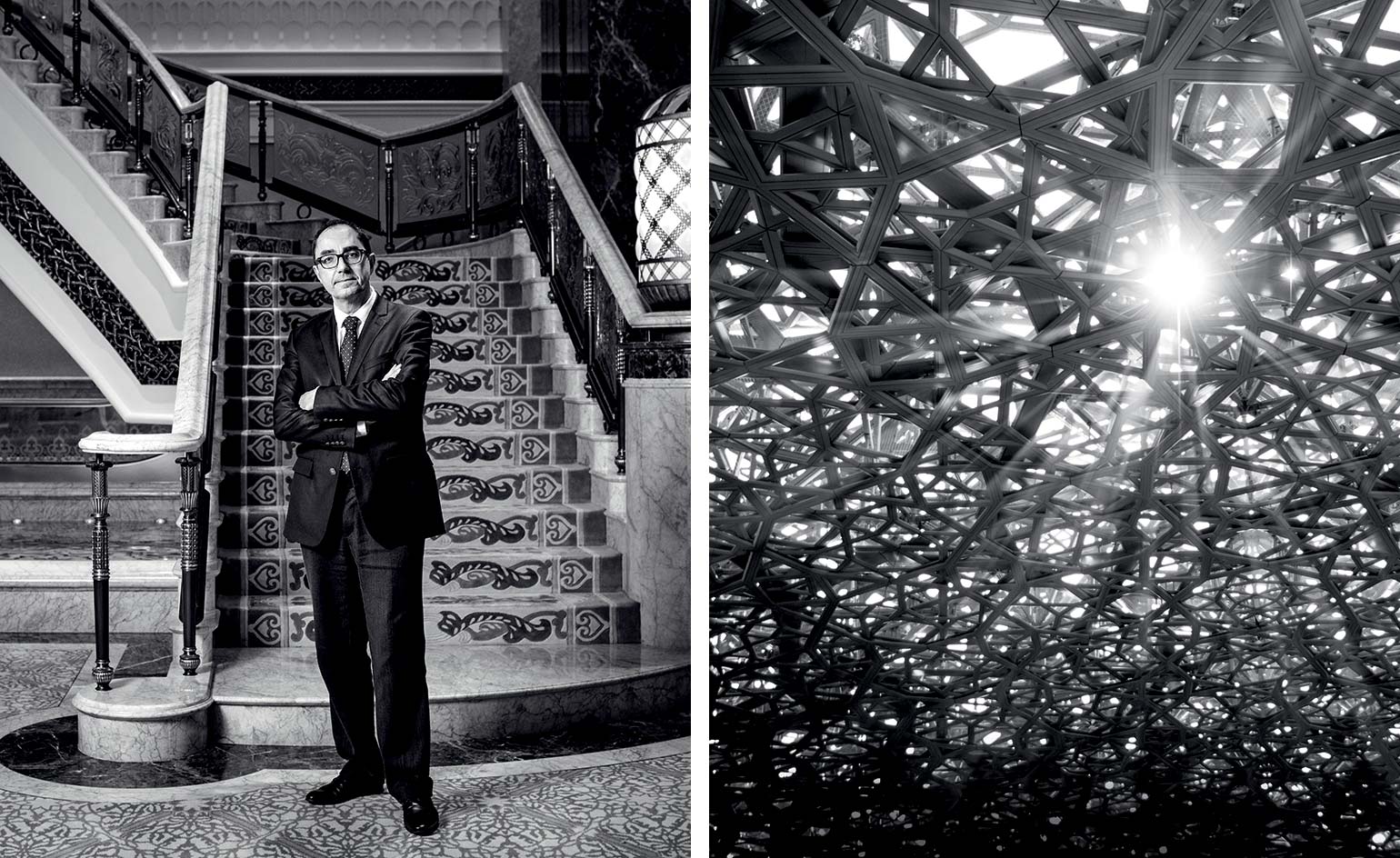

The Middle East is littered with big-budget grand projets that turn out to be white elephants. The Louvre Abu Dhabi cannot be allowed to become another. Too much face and too much cash is at stake. The man whose job it is to guarantee success, and who therefore sits in the hottest seat in the desert, is Jean-Luc Martinez, the president-director of the Louvre. Wallpaper* caught up with him in Abu Dhabi in December for his first interview about the project.

The museum’s 600ft-wide concrete dome weighs 12,000 tonnes. Render: Ateliers Jean Nouvel

We meet in a building that could not be more different from the Louvre: the over-sized, over-gilded Emirates Palace hotel, where a vending machine dispenses gold bars. Martinez is clearly enjoying his time in Abu Dhabi, despite the pressure. ‘In the career of a curator, it’s a rare opportunity to build a new museum with such ambition. It is quite usual to build new museums in Paris, London or New York, but nothing like this,’ he says, gesturing towards Saadiyat. He is also, he admits, ‘a little bit terrified’. That’s not just because French national pride and big reputations are on the line. From the day it was announced a decade ago, the project has been embroiled in the kind of controversy that the art world rarely experiences, and struggles to handle.

Many in France and further afield are aghast at the idea of the Louvre creating ‘a branch’ outside the country. Franchising is for McDonald’s, they sniff, not for a treasured national artistic institution that has been France’s bastion of high culture since 1190.

Martinez retorts that the Louvre Abu Dhabi is not a branch of the Louvre. Nor is it even French. ‘It is not for the Louvre or, indeed, for France,’ he says. ‘It is a new museum for Abu Dhabi. It is from this country, by this country. We are working for current and future generations here in the UAE. That is its heart. Bon!’

Martinez points out that the Al-Nahyans have acquired more than 600 works ‘from the earliest period of civilisation to contemporary’. The Louvre itself and other French institutions, including the Musée d’Orsay and Centre Pompidou, will supply only half that number on revolving annual loans, including works by da Vinci, Manet, Matisse and Monet, many of which have never left Paris. The number of loans will reduce over time, so that the museum becomes the near-total preserve of the UAE.

The aim, Martinez says, is to create the first museum in the Middle East that uses art and other artefacts ‘to tell the story of humanity from its earliest days to the present time. We want to show that every culture in the world can be presented together, working in the same direction.’ To help achieve this, works will be arranged chronologically, not by region or civilisation.

The Middle East is the perfect spot for such an institution, Martinez insists. ‘This region was, historically, the bridge between Asia, Africa, India and Mesopotamia and modern Iraq. In today’s globalised world, it has become the transport crossroads of the planet, linking East and West, China and Africa, China and Latin America. In the Louvre in France we have a French view of the world. Here we have a global view.’

The timing is pretty good, too, he argues – albeit for uncomfortable reasons. When the ancient cities of Palmyra, Hatra and Nimrud have suffered the destructive wrath of the so-called Islamic State, when tourists have been murdered in Tunisia simply for going to a museum and when a US president has banned travellers from some Muslim-majority countries from entering America, you can scarcely spend too much on promoting understanding between East and West, Martinez believes. ‘It is very important for a European museum to create an opportunity here to see the world outside Europe, to try to understand other audiences.’

Fine. But what about all that cash? What does Martinez say to those critics who argue that the Louvre is ‘prostituting’ its name and renting its treasures for grubby petrodollars? And there are many of them. When the ‘deal in the desert’ was announced, an online petition in France titled ‘Our museums are not for sale’ quickly drew several thousand signatures. French art historian Didier Rykner accused the Louvre of ‘pillaging’ its treasures. Catherine Goguel, emeritus director of research at the Louvre’s own prints and drawing department, dismissed the deal as a bribe to induce the Louvre to lend its seal of approval and integrity to what is merely the artistic version of the leisure theme parks being built all over the Gulf.

‘I can understand these questions,’ Martinez admits. ‘Let me answer. The Louvre is not a brand. We are a cultural institution, a name and a story. We do not and will not sell anything. We are lending to the Louvre Abu Dhabi. That’s normal. We and others do that all the time, all over the world. Yes, we have sold our expertise, but it is normal to sell expertise, too.’

But what about the extraordinary fee for the right to use the Louvre name for the next three decades? Surely that’s flogging a label? ‘We have a legal duty to protect our name,’ he replies. He won’t say it, of course, but the dune of petrodollars comes in handy when state funding of the arts across the world is tight and getting tighter.

What does Martinez make of Goguel’s suggestion that Saadiyat will be an artistic theme park, little better than the gaudy, go-faster Ferrari World complex next to the Formula One circuit on the neighbouring Yas Island? ‘Is the Louvre in Paris a Disneyland for art? No, I don’t think so. It is the same thing here.’ He pauses and adds: ‘Remember, Disneyland is now near Paris, too, but people still go to the Louvre. People can do both. People do not have to choose between sport and culture, between cinema and reading.’

One thing people certainly will choose to do is come to enjoy Nouvel’s unique structure. Architecture is a big draw, as the Guggenheim in Bilbao has proven. ‘These days, it is part of the success of a museum to build impressive architecture, and that is what Jean has done,’ Martinez says. ‘I love the scale of the building. I feel like I am in Paris at the end of the 19th century during the building of the Eiffel Tower. People will come to admire it, just as they do the Eiffel Tower. Some people will come only to have a walk. It is part of the pleasure.’

What no one knows is how many people will actually walk inside after the initial flurry that will surround the opening, expected this autumn. If you visit the other great new museum in the Middle East – IM Pei’s £3bn Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar’s capital, which opened almost a decade ago – it is often eerily quiet.

Fears that some new branded museums and galleries will not attract enough visitors or will prove too costly have prompted the Smithsonian, the world’s biggest museum and research complex, to abandon its plan for a bespoke outpost in London. Helsinki recently decided it doesn’t want to be home to the latest Guggenheim. Does Martinez ever wake up in the middle of the night worrying that the galleries will be so whisper-quiet that the new musée will feel more like a mausoleum than a celebration of the finest achievements of mankind? Or, to put it more bluntly: how many people will come?

‘I don’t know,’ he concedes. ‘But the strategy of the Louvre Abu Dhabi is to focus first on the local audience. Visitors from China and India are less than two hours’ flight from Abu Dhabi. These two groups will compose the core of visitors.’ It’s telling that he won’t venture a number. Not even a guesstimate.

Qatar’s attempts to use IM Pei’s museum and other galleries, some also designed by Nouvel, to rebrand itself as a cultural oasis have run into the sand over the issue of freedom of expression. Three ancient Greek statues of male nudes that were due to form part of an Olympic exhibition in Doha were removed after local ‘cultural objections’. There have been other squabbles over what can be shown. This has led critics to argue it is wrong for Western art institutions to bring the fruits of the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and the intellectual adventures of modernity into a region where freedom of expression is limited.

‘We have shown nude paintings here in Abu Dhabi,’ Martinez retorts. But he concedes: ‘This is not a French project here. We have been invited here, so we have to be polite and clever. We have to work with the perceptions of people here. It is a fact that nudes are less visible here than in Europe.’

So he is self-censoring? ‘It is not censorship. It’s because we are not a French museum here. It is the same in other countries. When we work in China on an exhibition we do not do things in the same way as we do them in Europe.’

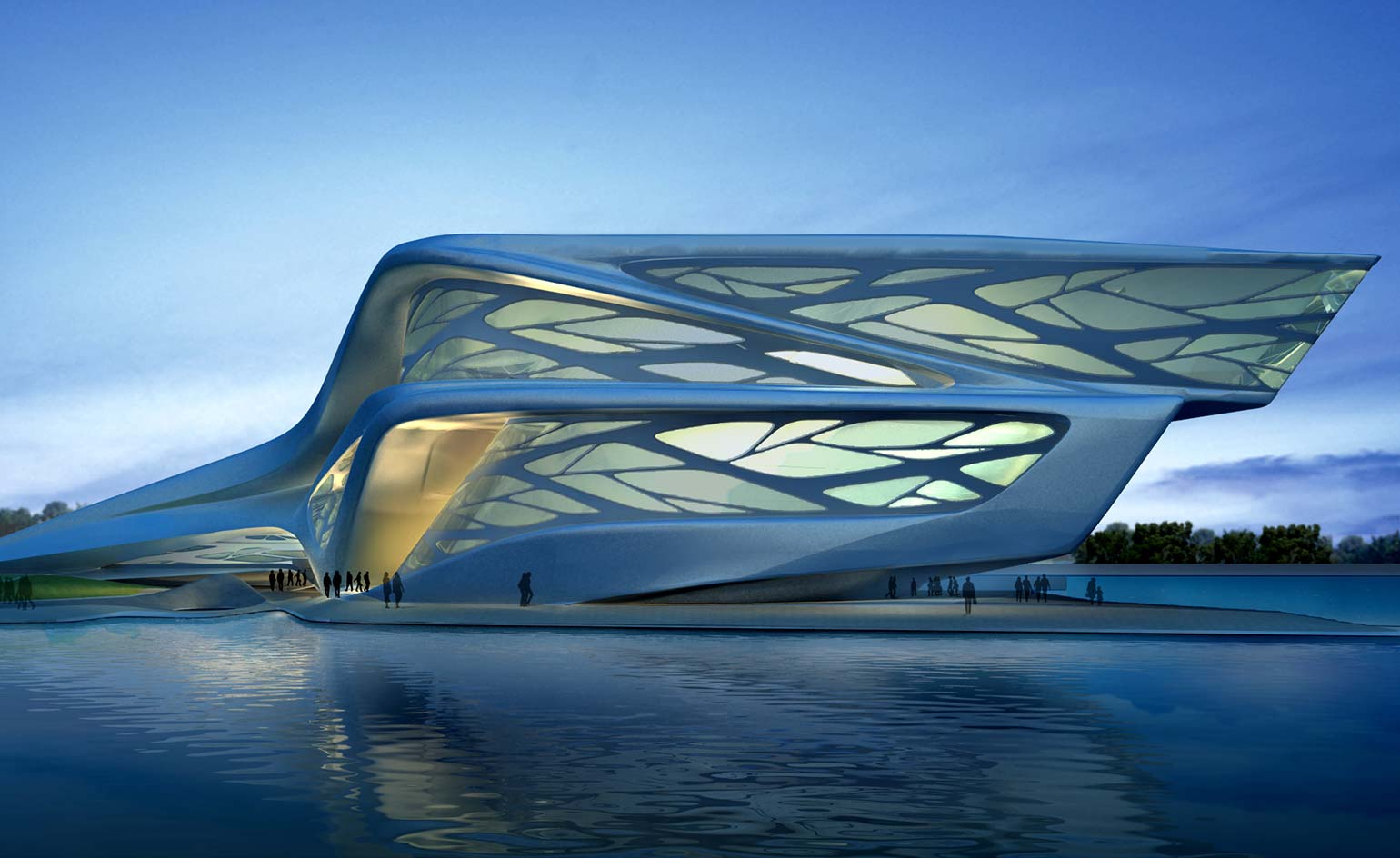

Abu Dhabi Performing Arts Centre, by Zaha Hadid. Hadid's organic structure, which looks like a flower bud washed ashore and about to bloom, will house five theatres with seating for a total of 6,300 people.

Martinez stresses the importance of la politesse not simply to justify the choice of works that will be displayed in the new museum. French hauteur has caused a rift between the Louvre and the Al-Nahyans. The French newspaper Libération has published a leaked private letter of complaint from Sheikh Sultan bin Tahnoun Al-Nahyan, a leading Abu Dhabi royal, in which he complained that the French were arrogant and had failed to keep their promises. Humility ‘can be difficult for a Frenchman’, Martinez says, with a knowing smile. Does that mean the French, the Louvre, have behaved in an arrogant way? ‘Maybe,’ he concedes. ‘We have to show humility. We have to listen and to serve.’

One big question that always dogs large projects in the Gulf is working conditions for the migrant labourers who build them. That goes double when you are creating a cultural institution on an island whose name means ‘happiness’. Human rights campaigners say contractors in the Gulf work crippling hours for low pay and have few opportunities to return home to see their families. Is Martinez satisfied that the sun-baked army of Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi men who have laboured in 45°C heat to build such a modern structure are not the victims of medieval labour practices?

‘To be honest, yes,’ he says. ‘I am not working on this building site myself, of course, but I have visited the village of the team of workers. I have asked the Emirati authorities to do their best and I am sure they did it. I can look at my face in the mirror and feel good.’

Many critics will regard that answer as too soft. But Martinez can give it because his building is built. The Guggenheim – which is supposed to be creating a £2.5bn Frank Gehry-designed outpost next to the new Louvre, as part of the Al-Nahyans’ £25bn masterplan to turn Saadiyat into the 21st century’s largest new art cluster – is less fortunate. It remains at the centre of an international storm of protest over the employment rights of the labourers lined up to build it.

As Martinez prepares for the very grand opening, I wonder what the future will bring. Could Abu Dhabi soon become as important a city on the global artistic grand tour as Paris, London and New York? ‘Yes. I am sure,’ he says. ‘Look at history. At the end of the 19th century, American museums were not so important. But now the Getty, the Met are very important. The same transformation can happen here.’ It will help if the other four museums planned for Saadiyat – the Guggenheim, the Zayed National Museum by Foster + Partners, a maritime museum by Tadao Ando, and a performing arts centre by the late Zaha Hadid – are built. The Al-Nahyans insist they will be, but, thanks to the financial crisis and low oil price, they remain a chimera.

And what of the future of France’s leading cultural institution? Could the Abu Dhabi joint venture be a model for other new Louvres around the world? ‘If another country wanted such a project, why not?’ Martinez says, with a smile. The only thing is, it could not be anywhere else in the Middle East. ‘There is an exclusivity clause in our contract with Abu Dhabi for this region,’ he reveals. Could he open a Louvre in Doha? ‘No. We are not able to.’ Purists, steel yourself for the Louvre Kazakhstan.

As originally featured in the April 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*217)

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Louvre Abu Dhabi website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.