Commedia show: Max Mara prizewinner Corin Sworn takes a theatrical turn

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

When I meet Canadian artist Corin Sworn, recently returned from six months in Italy to her adopted city of Glasgow, she is completely, unapologetically in love. The object of her obsession does not ride a moped, nor does it have anything to do with gorgeous sun-beaten colours or masters of the Renaissance. It is what she describes as the ‘loud, wild, licentious, sometimes problematic’ commedia dell’arte.

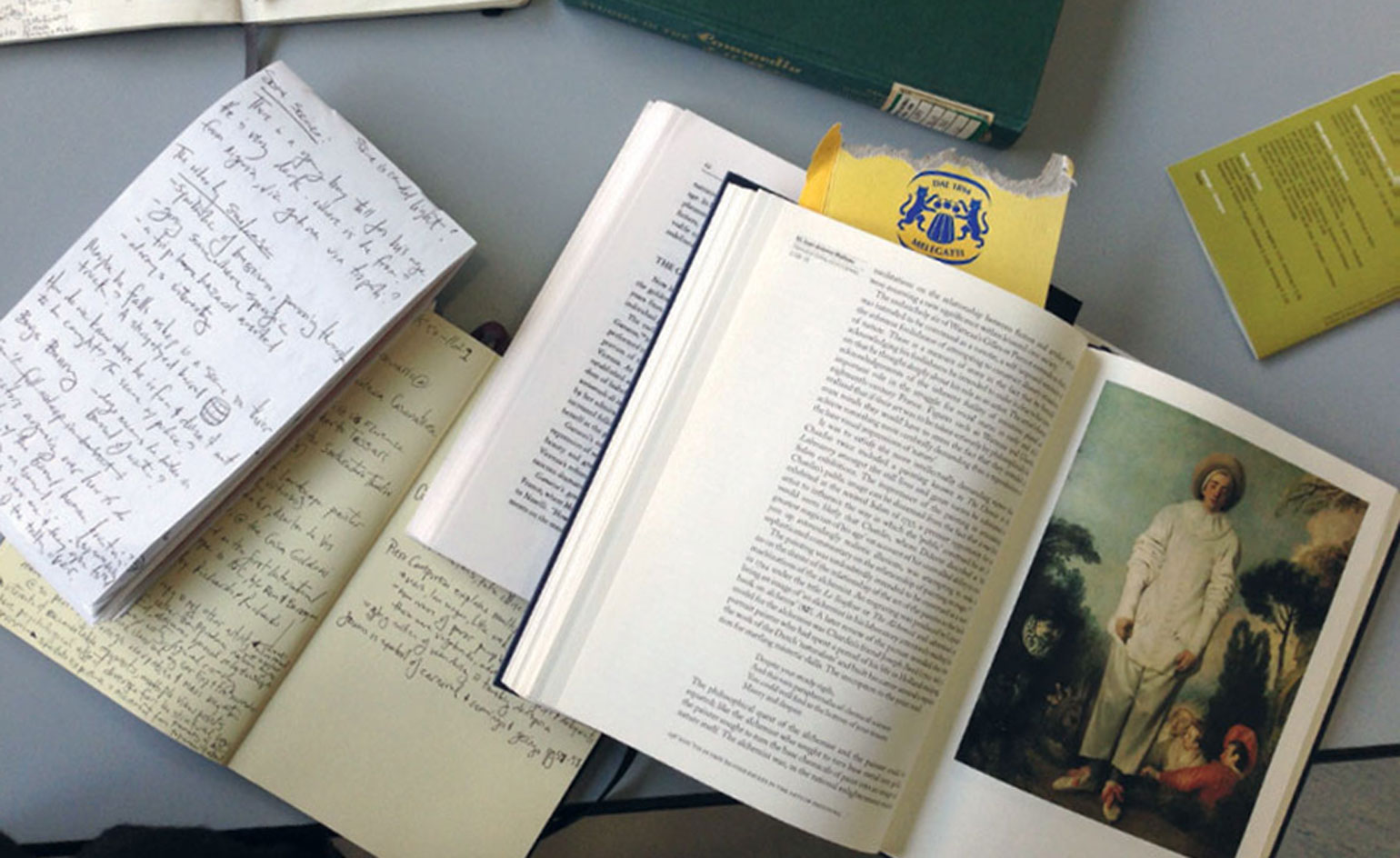

Sworn’s studio space, on the top floor of a warehouse overlooking the city, has become an immersion den. Books on the subject are everywhere; photocopies of library articles spill out of plastic bags; old prints of famous commedia masked characters (sassy Columbine, greedy Pantaloon, wily Zanni) are scattered around along with cuttings of costume sample fabrics.

Sworn is the fifth winner of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women, picking up the award early last year. The golden ticket as far as opportunities for young female artists go, the prize funds one rising UK-based artist on a dream research trip across Italy, and includes an invitation to show the fruits of her travels in a solo show at London’s Whitechapel Gallery.

Sworn was awarded the prize for her proposal to research the social origins of the commedia dell’arte in Mannerist Italy by spending time in and around some of the cities where early touring troupes originated. What attracted Sworn to the subject was her belief that there are little-explored dimensions to commedia that have contemporary relevance – particularly aspects of movement and expression which illustrated history books can’t capture.

Sworn makes installation and film works that reflect on social and cultural history. She’s previously had work shown at Tate Britain and Whitechapel, but her breakthrough was her well-received solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 2013, where she was one of three artists representing Scotland.

Sworn approaches all her material in a scholarly way, even describing herself as an academic. The wellspring of her inspiration is invariably the world of critical ethnographic ideas. Her interest in touring theatre stems from her fascination with its ability to transcend differences in language and class. The advantage of commedia’s unscripted, impulsive nature, and its gypsy-like movement across regions and countries, is that it gave actors a licence to break rules and challenge hierarchies. ‘The early plays broke through the class barriers of the day. These pieces would be performed both in market squares and at royal weddings.’

The contents of Sworn’s laptop testify to the breadth and depth of her research. An archive of hundreds of images includes antique costumes, actors learning commedia traditions, Palladio’s 16th-century trompe l’oeil theatre in Vicenza, a commedia-inspired puppet show put together by an eccentric actor in a Naples street, and studies of street theatre audiences. One shot is a detail from a painting by Vittorio Carpaccio she snapped on her iPhone in Venice. Carpaccio, the son of a leather manufacturer, paints in splendid detail the lithe-leged young posers in Venetian streets during the 16th century. ‘Look at those tights. Look at all these young dudes,’ she says.

Facts and theories about the place of theatre in mid-16th century society bubble up constantly in our conversation. The whole scene is worthy of a Borges story – a mad scholar wilfully conjuring the life and essence of the past in order to funnel it into the future. It’s a process she grapples to express: ‘I think that’s what I find a bit of a battle: how do you make a historical object, like a costume, how do you make action happen around it so that it’s employed in a way that allows us access to other ways of thinking?’

Born in London in 1976, Sworn grew up in Toronto, before studying for her BA in psychology and art history in Vancouver. ‘I was lousy at essays so I decided I’d take an art class. That way I could explore the ideas I was intrigued by but I didn’t have to write papers.’ She went on to do her MFA at Glasgow School of Art and still lives there with her partner, artist Luke Fowler, and their young son. ‘Someone told me Glasgow was like Vancouver because it’s not an enormous city but has a very strong art community,’ she says.

The ‘Glasgow miracle’, a term coined by curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, is common parlance in the city because seven Turner Prize winners have either lived or studied there. Sworn puts the Glasgow miracle down to open-mindedness. ‘People turn up at exhibitions ready to be surprised and spend time trying to come to terms with work that they’re not used to. That helps build a strong community.’ What Sworn has described are the same qualities she looks to encourage in her audience. ‘I want to make people encounter objects in a way that’s counter-intuitive to the way we read things now. These days cinema uses the face as a way of gauging an actor’s emotions on a micro-level. That had never happened in the past.’ She opens a book on a beautiful picture of commedia’s most famous character: Harlequin, the melancholic fool. In the picture he’s crying. Sworn copies him using her thumbs, hands and arms to portray emotion – an action ridiculous to us in its simplicity and emotional extravagance yet, she points out, fresh and moving to a contemporary.

Her research also took her in a direction she hadn’t foreseen when she hit on a little-explored theme, and one that struck her as being particularly relevant: the role of women and costume – or more specifically, women liberated through costume. (Max Mara has been so delighted by this turn of events that it has agreed to create costumes for Sworn’s show at its headquarters in Regio Emilia, northern Italy.)

Commedia was the first form of theatre to foster thinking actresses, and Sworn has used its cast of feisty feminist characters as inspiration for the performance and installation she’s planning at the Whitechapel Gallery. ‘Columbine, for example, could be agile and notoriously quick-witted. In one of the more famous stories she would play games of cross-dressing. She dressed as both defence lawyer and prosecution, then performed a battle with herself.’

But if there is a feminist drive behind her show at the Whitechapel, it’s gentle and teasing. Before Sworn closes her laptop she giggles at a picture of a Roman marble statue, a coquettish Venus with her towel slipping. ‘I thought I could use something like that in the performance, when the actress is cross-dressing. What if she just happens to moon the audience?’ she says. ‘I’d love it to be a little bit naughty.’

Originally printed in the June 2015 edition of Wallpaper* (W*195)

Research photograph taken for the project

Research photograph taken for the project

Research photograph of marionette bottle stops found in a market in the Pigneto district of Rome

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.