Cecilia Vicuña: the artist reclaiming oppressed histories with vigour, resilience and love

As Cecilia Vicuña opens her long-awaited Hyundai commission in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, (titled Brain Forest Quipu and on view until 16 April 2023), we revisit our recent interview with the Chilean artist, poet and activist

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

You might have seen the work of Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña before. You might have been staggered by its scale, its command of materials, or its ability to envelop space and all who encounter it. But you might not know all that Vicuña’s work stands for, or all it took to get here.

Vicuña has the sort of speaking voice that doesn’t demand attention. It’s quiet, dulcet and melodious. What she says, however, warrants undivided attention, an advantage she and her work have long been denied.

For most of Vicuña’s prolific 50-year career as an artist, poet, filmmaker and activist, she has been ignored, censored, marginalised, and ridiculed. When we meet at her studio, in the Tribeca district of New York, she explains that this alienation has its roots in the West’s ‘mastery’ in denying all that matters to people, the Earth and the future. This, she notes, is not just a story about how the Global North has excluded the South, but how the South has excluded itself by only embracing a Northern mentality. ‘All knowledge that disagrees with the Western system is eliminated, sometimes brutally, like in the current extermination of Indigenous people around the world’, she explains as a thread of incense billows through the air between us. ‘The Western mind is not just Europe and the US, [it] also operates in the colonies, and I consider Chile, even today, a colonised country where everybody is subjected to a colonisation of the mind, spirit and soul. So how could my work be meaningful under those conditions?’ In light of her potent and steadfast opposition to this oppressive landscape, Vicuña ‘never expected or looked for appreciation [or] recognition.’

Hyundai Commission, Cecilia Vicuña installation view at Tate Modern 2022. Photography © Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood)

Now, in 2022, Vicuña is having what is known as a moment. In April, she was honoured with the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 59th Venice Biennale (where she has an installation in the main exhibition, ‘The Milk of Dreams’); she’s the subject of a major survey show at the Guggenheim in New York, and later this year, she will dominate the nave-like cavern that is Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall for the 2022 Hyundai Commission.

Is she frustrated it all took so long? ‘Incredibly, no,’ she says. ‘This is true and not completely true, because what happened to me is the reason I was able to continue doing what I was doing; I found souls, people, that believed in what I did.’

Born in 1948 in Santiago de Chile, Vicuña spent her early years in the Maipo Valley, enveloped in a liberal rural environment where being clothed was actively discouraged (‘my mother believed that clothes were detrimental’, she says), and education and creativity were nurtured (her father even built her a garden studio for painting). ‘The whole family knew I was an artist [at] two years old,’ she laughs. But her childhood was not entirely

drenched in freedom. Her grandfather, a historian, was jailed four times for defending civil rights in Chile, and her family frequently took in refugees from the Jewish diaspora and the República Española following the Second World War.

Top and Above: Cecilia Vicuña Installation view, 'The Milk of Dreams', 59th International Art Exhibition: Venice Biennale, April 23 – September 25, 2022, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London

In spite of what was to come, Vicuña’s early life held a promise of swift success. At 18, her poetry was published in Mexico’s El Corno Emplumado (according to Vicuña, ‘the best poetry magazine that existed at the time’). At 23, she received two solo exhibitions at the National Museum of Fine Arts, Santiago. Vicuña believes this was only possible because it was the 1960s, a decade when minds were opened and ‘creativity engulfed the entire planet’. Then, in 1973, a wave of military coups arrived in Latin America, which deposed the democratically-elected Chilean president Salvador Allende and ushered in the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. This, as Vicuña puts it, brought ‘a closing of the mind, and the closing of all potentialities.’

As these events unfolded, Vicuña was in London, where she had enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Arts on a British Council scholarship and would remain in exile for three years (from 1975, she continued her self-exile in Bogotá, Colombia). ‘They asked me “which course do you want to follow?” I said, “I don’t want a course, I just want a studio”, so that’s what they did. I never had classmates’, she recalls. The studio was in Stepney Green, then a ‘brutal’ area defined by prostitution and deprivation.

In London, Vicuña was poor in material, but rich in ambition. She began searching for somewhere to show her work. She found the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) and proposed an exhibition. ‘I didn’t know that young South American girls didn’t do that. I was so naïve,’ she says. But Vicuña’s proposal fell into the hands of the ‘enlightened’ ICA co-founder, Roland Penrose, who requested that she visit him at the museum. ‘He said to me, “you are a great artist, but my board is absolutely adamant that you should not have an exhibition here”,’ she recalls. ‘“They think that you are worthless. But be sure, you will encounter this throughout your life, but you have to know within yourself that that’s not true.’ In spite of his board’s reluctance, Penrose managed to secure a space for Vicuna’s first solo show in London. ‘Pain Things & Explanations’ (1973) took place in the hallway leading to the ICA toilets.

‘Many years later, through friends who were scholars and researchers, I told this story and they searched the archives of the ICA and this exhibition, along with many other exhibitions, were not in their archives. Not in their records, like it never happened,’ she recalls.

In the late 1960s and 70s, Vicuña created a number of oil paintings, many of which were either lost or destroyed due to travel, the Chilean military coup, and a lack of care and respect for her painting practice. Vicuña estimates that, during her career, around 40 per cent of these works were thrown away. In 1986, she stopped painting entirely. She has only recently returned to the medium, reclaiming her history through reimagined versions of significant earlier works, driven by the lost paintings of her past. ‘Sometimes I wish they still existed, but I think an awareness of the precarious nature of our existence imbued everything that I did all along.’

Vicuña’s most recognisable works are installations called quipus. These monumental pieces rain from the ceilings of exhibition spaces in streams of raw, unspun wool and debris. They are an homage to, and contemporary reactivation of the ancient record-keeping quipus (made from long textile cords with a knot system) of the Incas and other ancient Andean cultures that bound communities but were banned by the Spanish during their colonisation of South America. Contemporary audiences may be surprised to learn that her first quipu consisted only of an empty cord – it was a ‘mind quipu’, perhaps an elegy to what was taken away, or an invitation to imagine what could have been. ‘All the quipus I have done come from the “mind quipu”,’ she explains.

Installation view of Cecilia Vicuña, Quipu del Exterminio / Extermination Quipu 2022, wool, natural plant fibers, horse hair, metal, wood, seashells, nutshell, seeds, bone, clay, plaster, plastic, and pastel, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul

and London

Vicuña’s exhibition at the Guggenheim is the premiere of a new three-part work titled Quipu del exterminio / Extermination Quipu (2022). Suspended in the High Gallery, a double-height space at the beginning of the museum’s spiral ramp, it’s at once an installation, a poem, and a call to action against the extinction of the Earth’s species. ‘Can we acknowledge extermination?’ asks a poem hand-scrawled in red on the wall behind the installation, inspired by texts by American theoretical physicist Frank Wilczek. ‘The quipu is the speaker of blood. Each knot marking a loss… a wound… the extermination of life.’

‘More than a year ago, before knowing exactly how the quipu was going to be, she asked for some silent time for herself in the High Gallery. This allowed her to use the Guggenheim spiral as a connector, connecting her with Earth and sky, and incorporating energy and millennial wisdom into the work,’ recalls Pablo León de la Barra, who co-curated the show with Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães. ‘Then [on] the day of installation she asked all of the team to make a circle in the space and hold hands. Incorporating her shamanic persona, she began chanting sounds and connecting us to one another, to the space, the building, her work and the energy of the universe. In the same manner, she did a prayer the day the quipu installation was finished, and now called it a prayer against extinction and for the Earth.’

León de la Barra first became aware of Vicuña’s work ten years ago while researching for an exhibition for the David Roberts Foundation (now The Roberts Institute of Art), which focused on Latin American artists who had been in political exile in London during the late 1960s and early 70s. ‘Although [Vicuña] has been based in New York for 40 years, the New York art world ignored her until she showed in Documenta in 2017’, León de la Barra notes. ‘On the other hand, this allowed her to develop her incredible and diverse body of work in silence and without the pressures of the art market.’

Installation view, Cecilia Vicuña: 'Spin Spin Triangulene, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum', May 27, 2022–September 5, 2022, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London; and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Titled ‘Spin Spin Triangulene’, the Guggenheim show is a focused offering of multidisciplinary work from the 1960s to today. Themes such as memory, language, science, cybernetics, and Indigenous spirituality and knowledge are explored through paintings, works on paper, language-based Palabrarmas (or ‘word weapons’, political and metaphorical riddles and poems which present language as a living entity), textiles, a site-specific quipu, and a one-time performance on 31 August of a ‘living’ quipu, commissioned by the museum’s Latin American Circle.

Lining the walls of the Guggenheim’s spiral are Vicuña’s paintings, which subvert colonial symbols, formats and media. Autobiography meets the rise of global socialism, alongside works that directly confront Frank Lloyd Wright’s museum architecture.

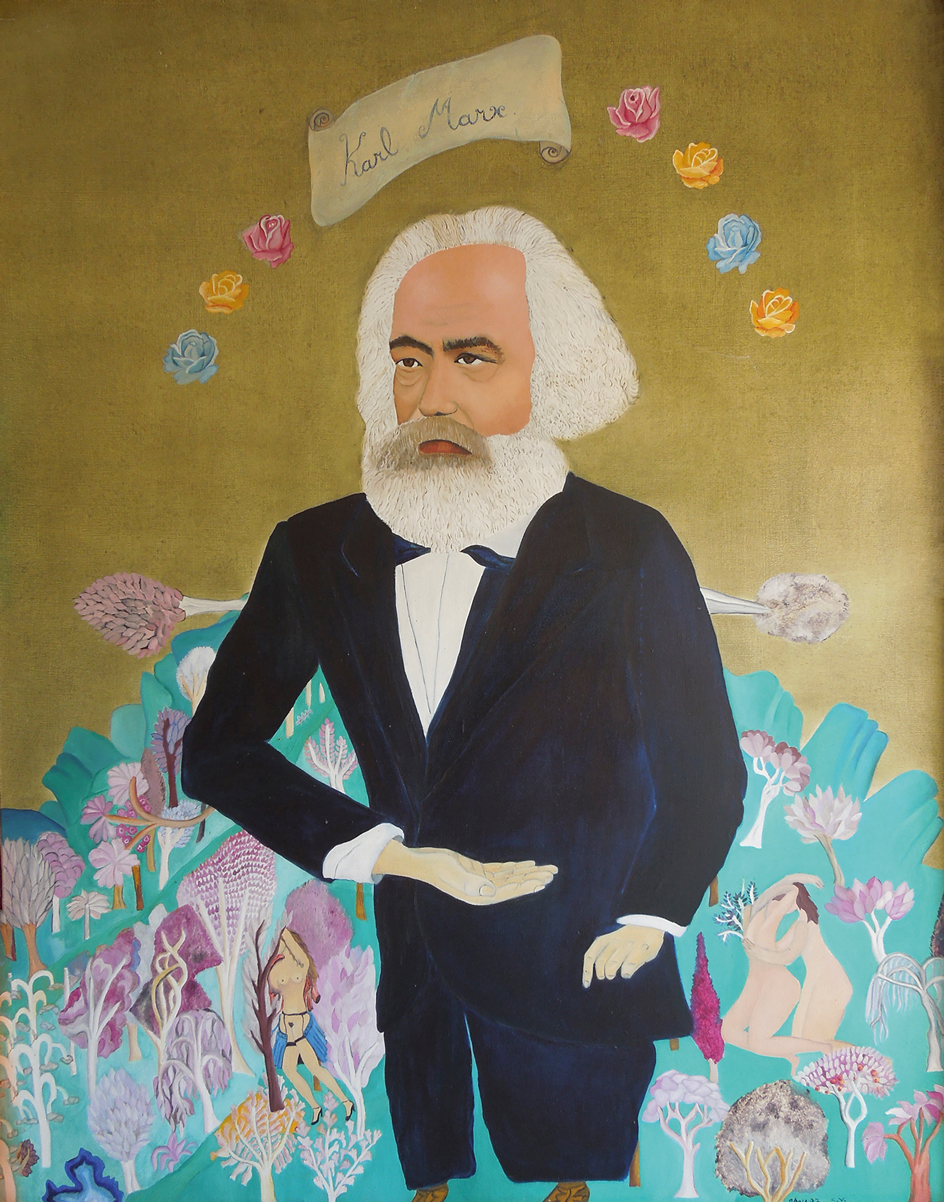

These include the deeply personal Autobiografia, which traces Vicuña’s life from birth until the work’s creation in 1971, and paintings of figures including Chilean folk singer and social activist Violeta Parra and German philosopher Karl Marx, which evoke religious icons. Vicuña presents Marx in a utopian ‘garden of eternal delights’ filled with amorous homosexual bodies. This painting has its own story of survival during Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile, when those who opposed the regime were openly persecuted. To prevent the work from being seized by authorities, Nemesio Antúnez, artist and then-director of Santiago’s Museum of Fine Arts, hid the painting in his home, painted over the name ‘Karl Marx’, and replaced it with ‘Charles Darwin’ (the evolutionary biologist had a similar white beard), an amendment since reversed.

Top: Cecilia Vicuña, Violeta Parra 1973, oil on canvas, Tate, Purchased with funds provided by Catherine Petitgas, 2017. Above: Karl Marx, 1972 oil on canvas, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Purchased with funds contributed by the Latin American Circle with additional funds contributed by Elisa Estrada, Camila Sol de Pool, Eugenia Braniff, Clarissa Bronfman, Mara and Marcio Fainziliber, Marianne Hernandez, Catherine Petitgas, Ana Julia Thomson de Zuloaga, and Rudy Weissenberg, 2017

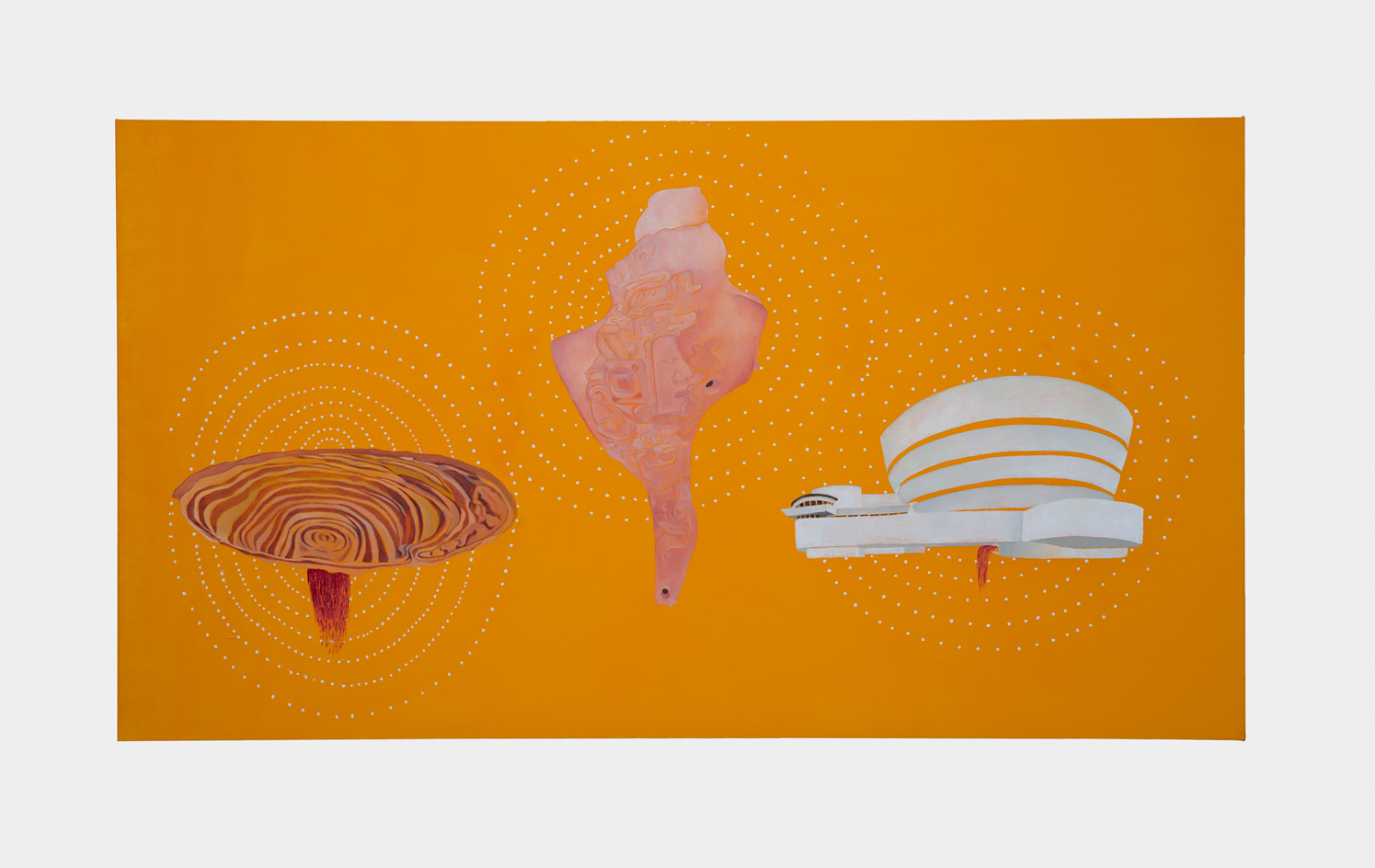

Another notable work in ‘Spin Spin Triangulene’ is the new painting, Three Spirals. It contains three images and three narratives, each distinct, but inextricably linked. On the left is Chuquicamata, the world’s biggest open-air copper mine, located in the north of Chile and owned by the Guggenheim family from 1912-23. In the centre is a spiralled conch flute, used by Mayans in sacred rituals. Mayan architecture in turn was a frequent source of inspiration in Wright’s work; a likely source of inspiration for the Guggenheim’s spiral form was the staircase of El Caracol (the snail), an ancient observatory at the Chichen Itza in modern-day Mexico. On the right is the Guggenheim itself, which appears to bleed with a river of red paint.

Vicuña doesn’t oppose the usual narratives around Wright’s design inspiration (the Guggenheim website references the incorporation of ‘organic form’ into the museum’s architecture), but instead poses an open question: is there more to this story? ‘Even though I’m not an archaeologist or an art historian, and I cannot say for sure, I wanted people to sense that an artist such as Frank Lloyd Wright also takes his inspiration from Indigenous art.’

With this question, Vicuña is addressing the foundations of the Western art world, specifically the history of the Guggenheim family and the source of its fortune in extractivism. It is noteworthy that a museum now celebrating Vicuña’s life and work had derived its early capital from destroying what the artist fought for an entire career to preserve. She contends that most museums around the world are entangled in capitalist exploitation. ‘The entire world is dependent on the destruction of the world, so it’s something that has to change if there’s a chance of surviving.’ That’s why I bring it up, because every chance we have to bring awareness to the deadly effect of extractivism, is something that every citizen should be involved in’, says Vicuña. ‘We are trapped in this complicity and this “looking away”, pretending that this is not the case. Now we have received the final warning from the scientists that the planet is becoming uninhabitable for humans.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Cecilia Vicuña, Tres espirales (Three Spirals), 2022 oil on canvas. , New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London; and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Installation view, Cecilia Vicuña: Spin Spin Triangulene, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, May 27, 2022–September 5, 2022, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London; and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

As León de la Barra explains, Three Spirals is questioning the ‘dependency today of the art system, institutions and artists on extractivist funding which has an effect on our fragile environment and climate change… Cecilia’s message is clear: if we don’t change our destructive ways and our relationship with our environment, our days on this Earth are counted.’

Throughout Vicuña’s paintings and installations are common threads, and they’re often a shade of deep, visceral red. This is red as the absolute core of humanity: life, death, blood, spirituality, the cosmos; the power of the female body, and its oppression. In her paintings and installations, red is murder, wounding, and menstruation, sometimes all at once. ‘The negative view of blood and menstruation is pretty universal. The patriarchy has been instilled in the entire planet, and nobody escapes that. But human culture is far older than the patriarchy. It existed for perhaps millions of years before the idea that blood was shameful.’

‘Red is incredibly important. I knew what it meant, this relationship or fascination, but I don’t think it would be in my art,’ she says. ‘

It is for each viewer to decide whether this is the blood of hurt, the blood of murder, the blood of destroying the Earth, or the blood of complicity. When we’re faced with blood, whether it is of our own menstruation or the blood of a wounded person, we have all this ambivalence in our response: disgust, horror, compassion. Red mobilises strange, profound forces within us.’

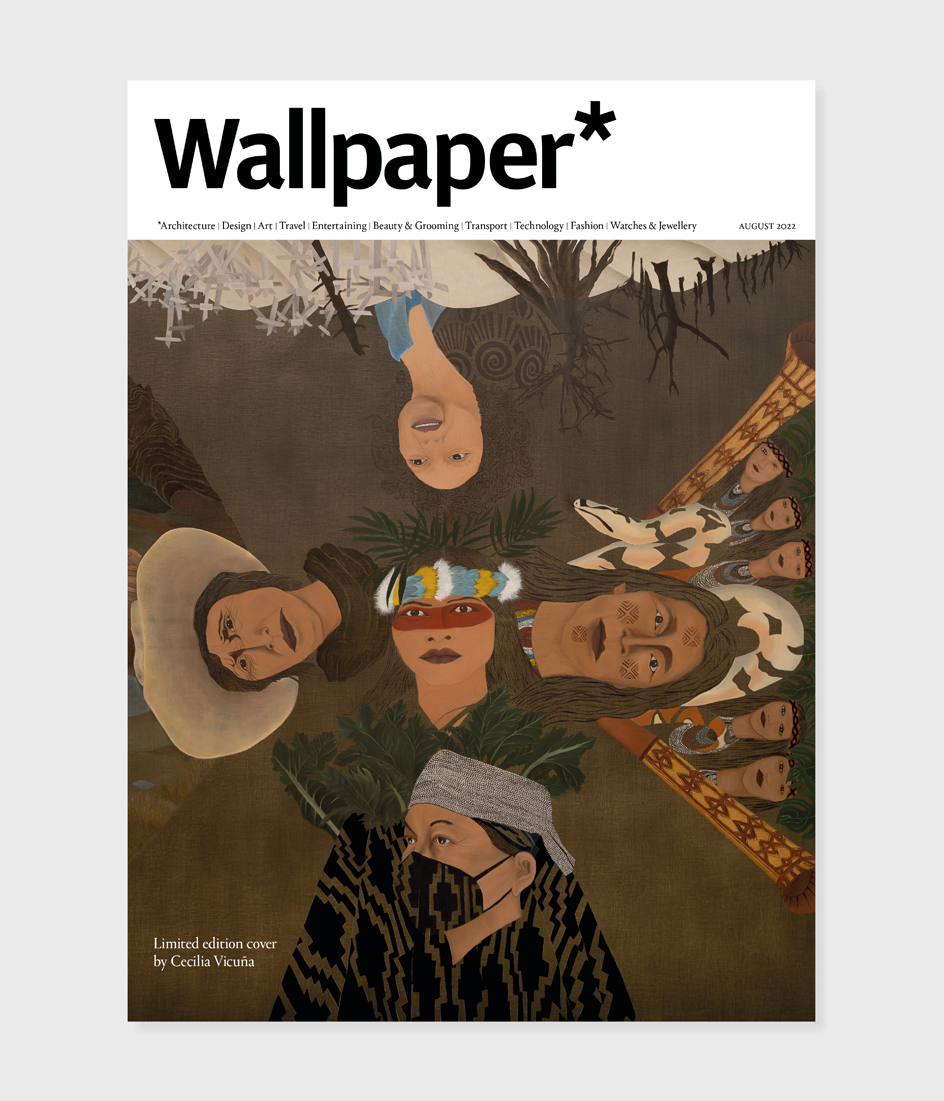

Above, the August 2022 limited-edition cover features Cecilia Vicuña’s Liderezas (Indigenous Women Leaders) (2022), an oil painting celebrating the vital role of Indigenous women leaders from Latin America

Vicuña created her first red quipu in 2006, the year that Michelle Bachelet became the first female president of Chile, and the first popularly elected female head of state in South America. Vicuña was unable to vote – the electoral register had been burnt by the dictatorship. ‘I wanted to vote! So I decided I would go up to the glacier that feeds Santiago, and [create] a red quipu at the foot of the glacier for the specific purpose of praying for the awareness of the union of water and blood.’

Another example recently dangled from the rafters of Tate Modern, where, in October, Vicuña will take on the ambitious Turbine Hall commission. Vicuña believes that the ‘very visceral, fantastic response’ to her monumental installation, Quipu Womb (2017), which debuted at Documenta 14 and was recently acquired by Tate, was part of the reason she was selected for the Turbine Hall.

Frances Morris, director of Tate Modern explains, ‘Vicuña has been an inspirational figure for half a century, championing concerns of ecology, community and social justice which grow ever more urgent today. Her radical textile sculptures combine pressing political messages with stunning visual form, creating a truly unforgettable experience for the viewer – one that resonates with and connects audiences all around the world. Recognition of Vicuña's powerful work is long overdue and I'm thrilled that she'll be bringing fibre art to the heart of Tate Modern for the first time this autumn.’

Installation view of Quipu Womb (The Story of the Red Thread, Athens), 2017, Cecilia Vicuña, on display at Tate Modern

Given her historical entanglement with London, Vicuña’s forthcoming Tate commission will offer a sense of coming full circle. ‘I have a love for London, where everything was so difficult and beautiful at the same time. The Turbine Hall, in particular, feels like a park, like a public space, and people use it that way. I’m fascinated by that because that’s the origin of my art,’ she says. ‘Whatever I do in the Turbine Hall will continue that spirit of complete fluidity of the public space. Even though it’s inside the museum, people take it differently, perhaps because it’s an industrial space, it belongs to everybody. Experiencing – not telling, but sensing, feeling – is the most powerful way of transmission.’

Vicuña’s artworks are living entities, with a gravitational pull stronger than their earthly weight suggests. They are circular, ephemeral, and in a sense, unfinished, much like our existence and purpose on Earth. Their message, at their core, is that eco-activism, feminism, and the rights of Indigenous people are not responses to distinct plights, but part of the same tapestry. Her work is a eulogy to all that’s been lost, and a plea to avoid what might be if we continue on our path of inaction and destruction.

Vicuña brings the Earth, its people, and its lost histories onto the stage to speak for themselves. Together, they proclaim that what weaves us together might just keep us alive, and the world spinning.

Portrait: Tina Tyrell

INFORMATION

‘Spin Spin Triangulene’ is showing until 5 September at the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York, guggenheim.org

Hyundai Commission, 13 October 2022-16 April 2023, Tate Modern, London, tate.org.uk

ceciliavicuna.com, lehmannmaupin.com

A version of this article appears in the August 2022 Design for a Better World issue of Wallpaper*, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today!