London's Royal Opera House unveils makeover by Stanton Williams Architects

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

The Royal Opera House is opening up. The ground floor foyer and the Linbury Studio Theatre at the beloved London institution have been transformed by Stanton Williams Architects; and this week sees the launch of the foyer’s extensive makeover, while the theatre’s complete reconfiguration is due to be fully operational by December.

It’s an ambitious scheme that took more than a little planning in what is essentially an incredibly busy and dense structure, explains the architects’ co-director Alan Stanton. ‘The Open Up project was an architectural aspiration to open up the building physically and culturally as much as possible to the general public’, he says.

‘[The brief] evolved massively over time. The building is so complex, it is absolutely packed with things’, continues Stanton, who points out that the original brief contained a new entrance and the moving of a set of shops on the Covent Garden side, a plan that was later abandoned due to cost and practical implications. ‘Essentially, we wanted to liberate public space. It was like open-heart surgery. We had Placido Domingo rehearsing in opera and we had jackhammers going on downstairs. But in the end you want it to look natural and effortless.’

The scheme, which kicked off in 2013 after a high profile international competition, creates a new, open foyer area on the ground floor, to connect the existing main auditorium to the renewed Linbury Studio Theatre below. The refreshed space now includes a new café, interval bars, cloakroom facilities, a shop and informal event spaces, as well as a wide landing and a set of steps in the reimagined Linbury foyer. These steps will double as an informal stage, to host a variety of performances and events for the public; these will now be visible both from the café area and the street.

This internal openness and porosity were important to both the architects and the institution. ‘Since a major redevelopment in the late 1990s, a generation of audiences and artists had moved on’, says Alex Beard, ROH’s chief executive. ‘Over that time, the nature and the setting of Covent Garden has changed, and expectations of public institutions changed. I firmly believe that great institutions should regard themselves and behave as part of the fabric of their cities and this project was an opportunity to do just that. Also, architecture is extremely important and powerful as a metaphor. The opportunity to have a window from the street into the ROH and for people to see that this building is full of activity and creativity and to be invited in whether or not you have a ticket in and of itself is a good thing; it also sends a strong signal.’

Equally important attracting visitors from nearby busy Covent Garden. The revamped ground level café is now informal enough for passers-by to make a pit stop to refresh and replenish, but also remains welcoming for longer stays too. It is also the ideal place for pre-show drinks.

The Linbury foyer will now double as an informal stage for scheduled and impromptu performances.

Stanton Williams worked with a careful selection of fine materials, such as stone from Alicante, patinated brass, stainless steel and polished plaster. Minimalist, brass cabinets behind the café’s long stone counter keep all the necessary tableware neatly tucked away. The foyer’s walnut wood cladding is at places left clean and butter-smooth, while in other areas has a ribbed effect to aide acoustics, provide subtle richness of texture and reference the building’s existing striped wallpaper. The architects chose Crema Marfil marble floors throughout the new public spaces; the material was selected for its durability and compatibility with the existing floors, helping to link old and new parts together.

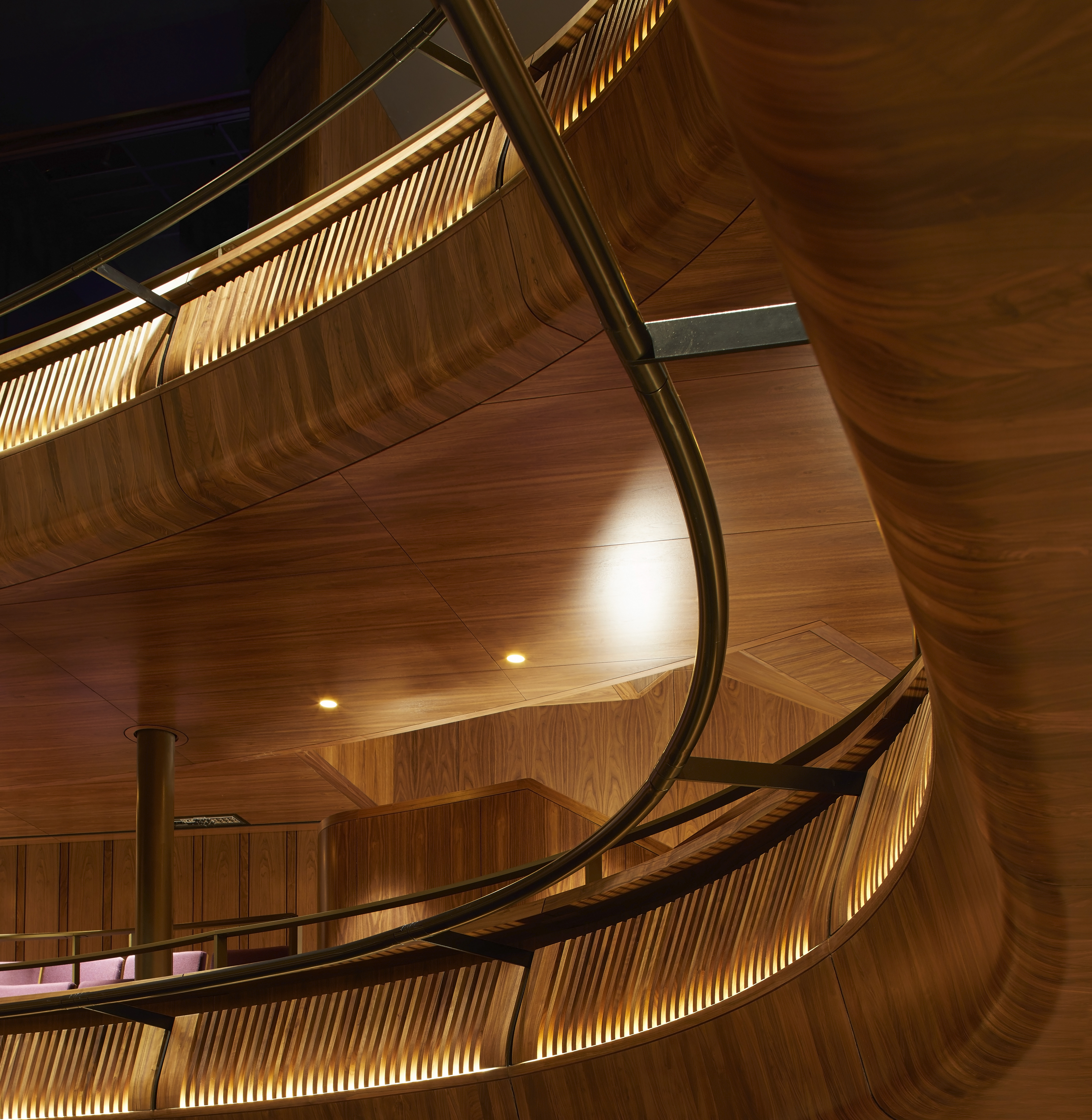

Clever reconfigurations were required in order to achieve this sense of openness and the ROH’s newfound ease of circulation. A new, repositioned ‘baby grand’ staircase at the heart of the ground floor replaced the lobby’s existing stairs in connecting the ground level foyer to the amphitheatre level bar and restaurant at terrace level above. The architects also freed up space on the ground floor by moving the ladies’ WC down to the lower lever. Now, the more functional and significantly larger modern facilities feature contemporary stone and a streamlined aesthetic.

Moves such as these don’t come without their challenges. The scheme required careful consideration as most building work took place while the ROH was fully operation (‘we haven’t lost a single performance or a single rehearsal’, says Beard). Engineers Arup and Robert Bird Group conceptualised and supervised the large, historical complex’s structural construction work. The Linbury's open foyer was crafted by gutting the space and clearing out existing walls and pillars with surgical precision and painstaking structural analysis; no mean feat, as the concrete pillars were about 2x1m thick and needed to be replaced by a large steel truss.

‘For us to extend this space – and that was vital part of the project – we went through a variety of scenarios. In the end we assembled this massive beam on site from components and inserted it’, recalls Stanton. ‘There were three different sets of engineers triple checking everything. It was a huge effort. They gradually nibbled away those great columns, we dug a great big hole, and then the light came in, the space expanded and everybody saw that it was absolutely worth the effort, liberating this space.’ At the same time, the theatre itself now has the most sophisticated stage systems for state-of-the-art 21st century performances.

American black walnut lines the display cases along one of the entrance walls, where content, such as photographs, music scores and costumes, from the ROH’s rich archives, will be displayed, highlighting that this is an ingenious architectural intervention designed to complement the art of performance. ‘It’s an architectural language that is highly refined but also very theatrical. Everything that we did within this project should be on the same level and ambition as what happens every night on stage’, says Beard.

See more about the Pioneering imagery captures balletic choreography for new Royal Opera House campaign

Part of the project was the main ground level foyer's extensive makeover, which spills over into the lower ground Linbury Studio Theatre's own foyer.

The revamped space is now sleek and modern, featuring lots of walnut wood.

The ground level features a welcoming modern café, for long and short stays.

A repositioned ‘baby grand’ staircase at the heart of the ground floor replaced the lobby’s existing stairs.

The Linbury Studio Theatre interior was entirely reimagined.

Modern facilities and streamlined timber cladding brought the space into the 21st century.

American black walnut also lines the display cases along one of the entrance walls, where content from the ROH’s archives will be displayed.

INFORMATION

For more information visit the website of Stanton Williams Architects

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).