Remembering Richard Rogers (1933 – 2021)

We celebrate the life and career of Richard Rogers, one of the most influential architects of our era and winner of the 2007 Pritzker Prize, who passed away on 18 December 2021 at age 88

As one of the most influential architects of our era, Richard Rogers had an immeasurable impact on the modern city. His studio brought artistry and elegance to everything from factories and warehouses to office towers, transforming the literal building blocks of architecture into their primary aesthetic expression. As a pioneering exponent of what became known as ‘high-tech’, Rogers and his peers realised the machine-age dreams of the first modern architects.

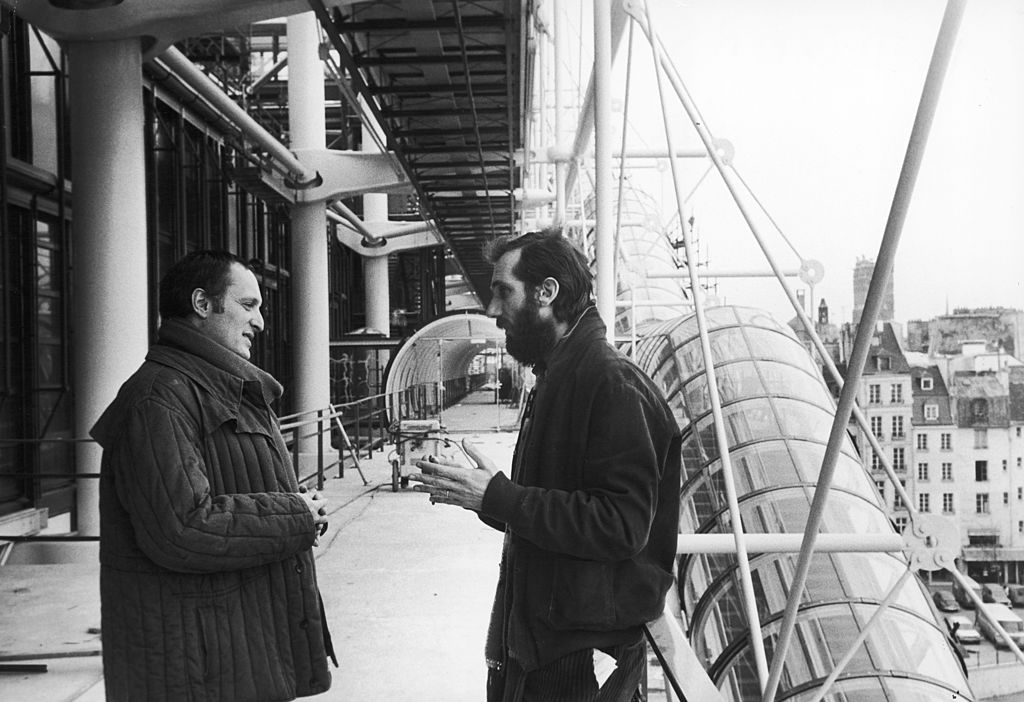

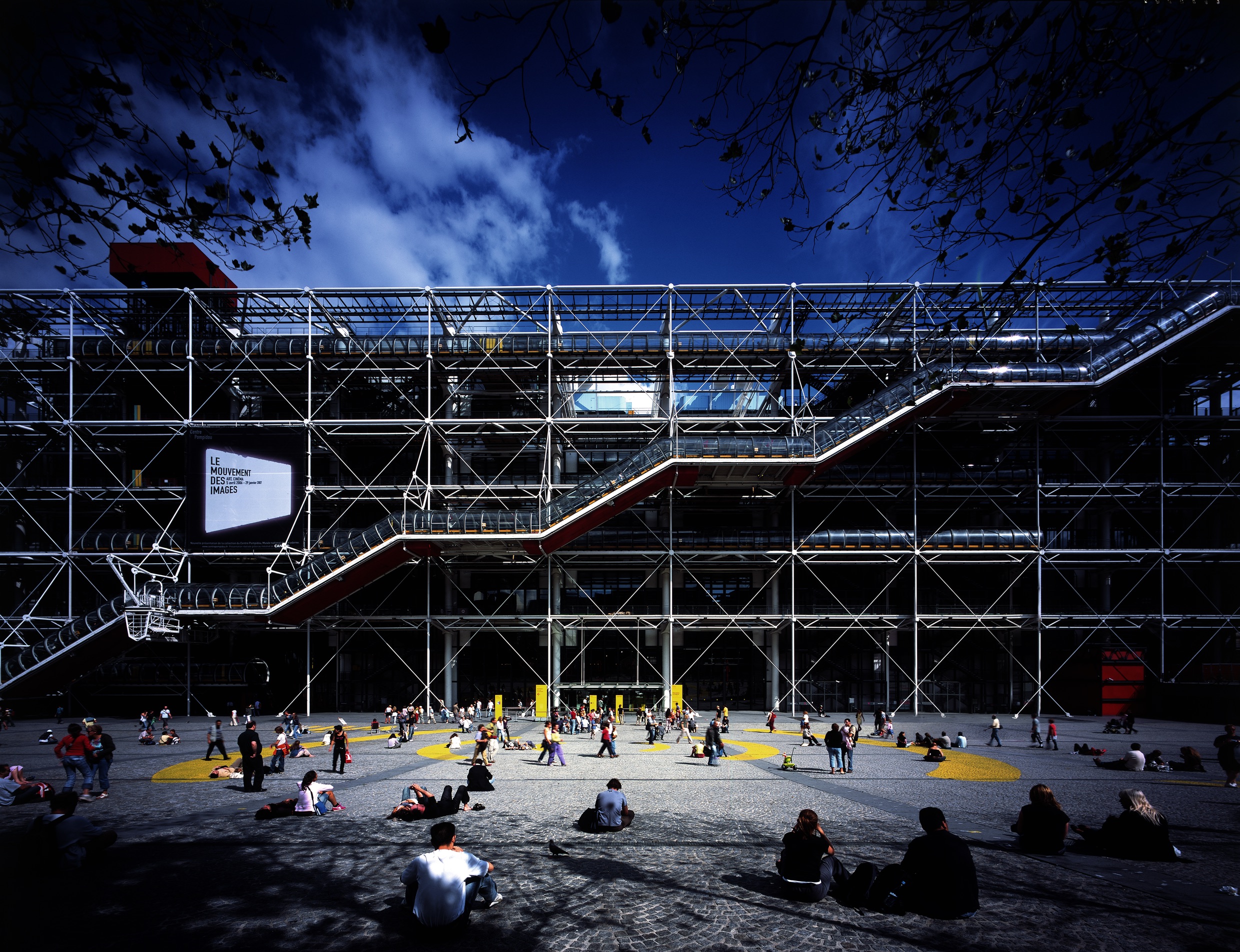

Born in Italy, Rogers studied at the Architectural Association and then Yale, where he met Norman Foster and Su Bramwell, later to become his first wife and partner, together with Foster and Wendy Cheesman, in Team 4 Architects, founded in 1963. After over a decade of experimental, pioneering practice, working mostly in industrial architecture, the studio fragmented, and the Richard Rogers Partnership was set up in 1977. The studio’s first major work, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, came to define an era. Devised in collaboration with another titan of the new industrial architecture, the Italian Renzo Piano, the Pompidou was the most prominent of the five projects the partnership completed. Drawing on the spirit of 1960s experimenters like Archigram, the arts centre created huge floor plates of flexible exhibition space by pushing all its services to the exterior. The result was a jigsaw of coloured pipework and snaking escalators that stood in striking contrast to the historic fabric of the city.

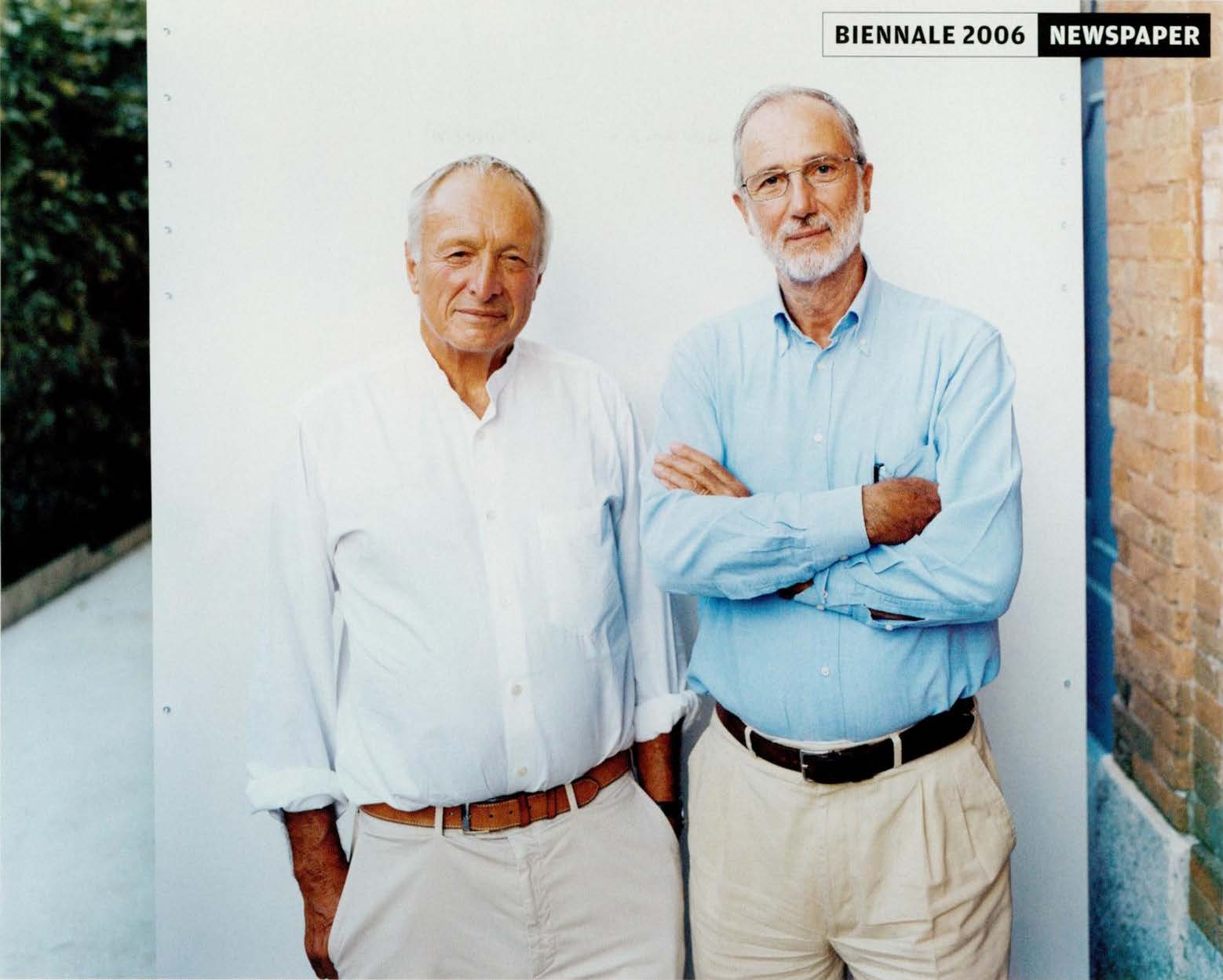

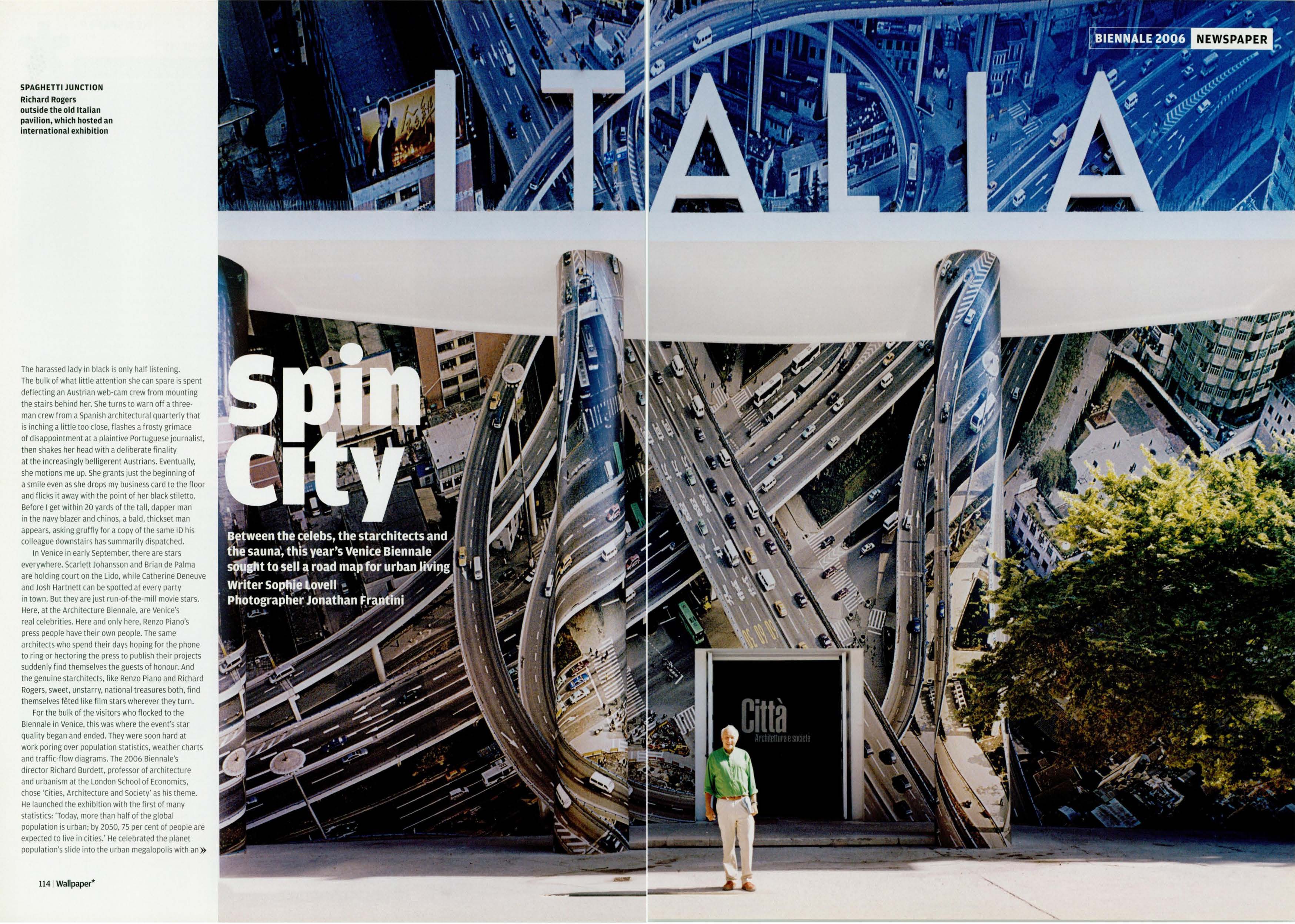

Top: Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano on the construction site of the Centre Georges Pompidou in January 1977. Above: Rogers and Piano at the 2006 Venice Architecture Biennale, for the December 2006 issue of Wallpaper* (W*94)

Piano went on to set up his own Building Workshop in Genoa, but Rogers, it seems, was destined to go from one epoch-defining building to another. The next project on the drawing board was a new office for Lloyd’s of London. Whereas Pompidou carried the loose fit legacy of 60s freedom into the 70s, the Lloyd’s Building presaged the rather more strait-laced and venal qualities of the 80s. It was corporate HQ as power suit, adopting the Pompidou’s infamous ‘inside-out’ qualities for the City streets, yet with a sober disavowal of colour; stainless steel and glass were the dominant materials. In the six years it took to build, technology barely had time to catch up with the vision and it opened in 1984, over-budget and highly controversial, but also undeniably brilliant. It was perhaps the first modern office building to capture the joy in detail that defined the great municipal buildings of Soane or Lutyens, swapping decoration for a delight in technology.

Richard Rogers created the limited-edition cover for the July 2013 issue of Wallpaper*, featuring a quote by the architect that appeared in AD magazine in the late 1970s after the Centre Pompidou was completed

In 1986, Rogers, alongside James Stirling and Foster, had an epoch-defining show at the Royal Academy. This was the architectural equivalent of Hugh Hudson’s cinematic war-cry: ‘The British are coming!’. High-tech architecture was deemed the true heir to the legacy of the country’s white hot technological revolution, a space age affirmation of the Dan Dare futurism that infused the post-war era. Rogers, however, never quite subscribed to his former partner’s love of the machine. RRP’s work was underpinned by a long-running obsession with urbanism and sense of social justice. Rogers’ commitment to big ‘m’ Modernism was firmly rooted in the movement’s socialist origins. Rogers had architecture in his blood. His cousin, Ernesto Nathan Rogers, was one of Italy’s leading post-war architects and the creator of the 1958 Torre Velasca in Milan, along with his partners in BBPR. There has always been a broadly Mediterranean approach to the role of society, family, culture and space in the Rogers office. The practice’s self-designed studios in Hammersmith were famous for being to adjacent to the River Café – co-founded by Rogers’ second wife Ruth. The practice itself limits its directors’ salaries to a proportion of the lowest wages, and there are generous employee benefits that have maintained a loyal, long-serving team.

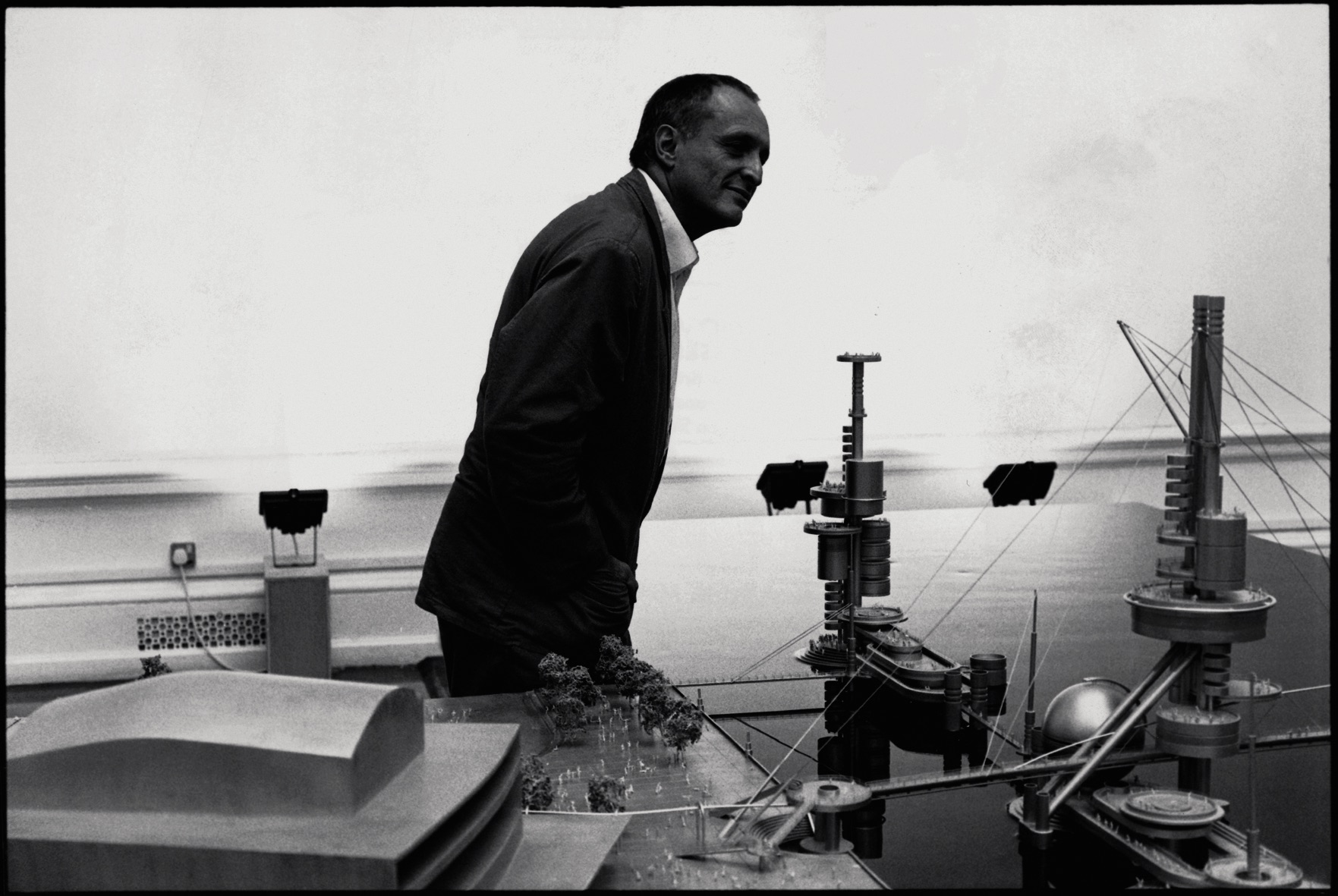

Rogers at the 1986 exhibition ’London as it could be’.

For a while, Lloyd’s’ industrial aesthetic led to a run of genuinely industrial projects, with schemes for urban design thwarted by funds or opposition. Massively complexity bred specialisation within the firm, and decade-long projects became increasingly common as clients approached Rogers’ team to untangle complex puzzles of urbanism and infrastructure. At the same time, the firm evolved a palette of materials, forms and colours, refining off-the-shelf components and developing their own bespoke solutions for the services and structure that shaped their works.At the pioneering, Philip Johnson-curated ‘Machine Art’ exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1934, industrial objects like ball-bearings and springs were placed on pedestals and celebrated like shiny abstract sculptures. Perhaps this point of divergence – one path to streamlining and machine-made purity, one path to naked mechanical fascination – is what divides Rogers from Foster. The latter might be said to have more discipline, more desire to see the machine subsumed by the sculptural potential of new material; but Rogers, on the other hand, finds not just aesthetic purity in mechanical innards, but a freedom of space and function.

Richard Rogers at the 2006 Venice Architecture Biennale, as featured in the December 2006 issue of Wallpaper*.

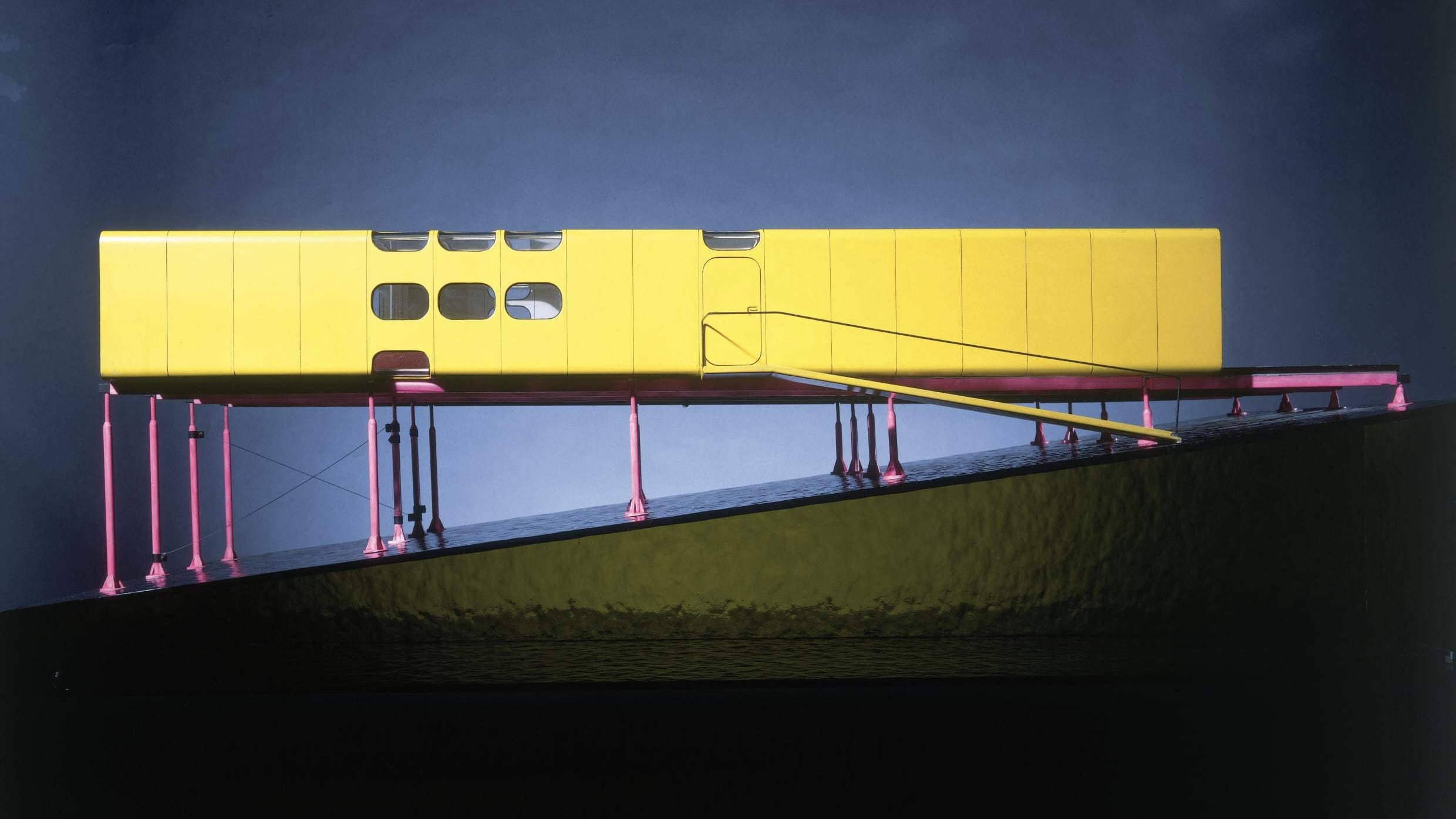

Inevitably, success has meant an increase in scale. From its inception, the Rogers Partnership has never baulked at grand projects. This has occasionally meant sticking his head up above the parapet and taking some political flak. It’s widely agreed that RRP’s Millennium Dome was the best thing to come out of the UK’s flawed year 2000 celebrations, a vast structure that subsequently fulfilled its flexible brief. Despite other well-publicised spats – most especially with the Prince of Wales – Rogers inevitably became an establishment figure, living in a grand Georgian conversion in the heart of Chelsea, receiving a knighthood in 1991 and taking a seat in the House of Lords five years later. Baron Rogers of Riverside can still rile the industry, only these days it’s the firm’s broad portfolio – running from the Homeshell experimental pre-fab housing unit through to London’s most expensive apartment building at One Hyde Park – that is sometimes at odds with its social conscience.

A view of Richard and Ruth Rogers’ home in London, including their collection of Wallpaper* magazines (left, on the low shelves) and a painting by Philip Guston. As featured in the April 2018 issue of Wallpaper*.

The practice’s own democratic structure is undiminished. In 2007, Ivan Harbour and Graham Stirk became senior partners and the name was changed to Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners. Rogers retired in September 2020, and his final project, the Drawing Gallery at Provence's Château La Coste, was unveiled in spring 2021. A small but spectaular building within an orange still frame that cantilevers out of a thickly wooded ridge, the building offered a powerful summation of the life and work of a visionary architect.

Experimentation and innovation are high on the agenda for Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners. Housed in 122 Leadenhall in the City of London – the firm’s own smartly designed spec office building, sitting over the road to the tailored perfectionism of Lloyd’s – upcoming projects include Terminal 4 at Shenzhen Bao'an Airport, a distillery for Horse Soldier Bourbon in Kentucky, the Hammersmith & Fulham Civic Campus in London, and H-Farm, a library and auditorium at the heart of a start-up education campus in Venice. Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners continues to offer a bold architectural vision.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

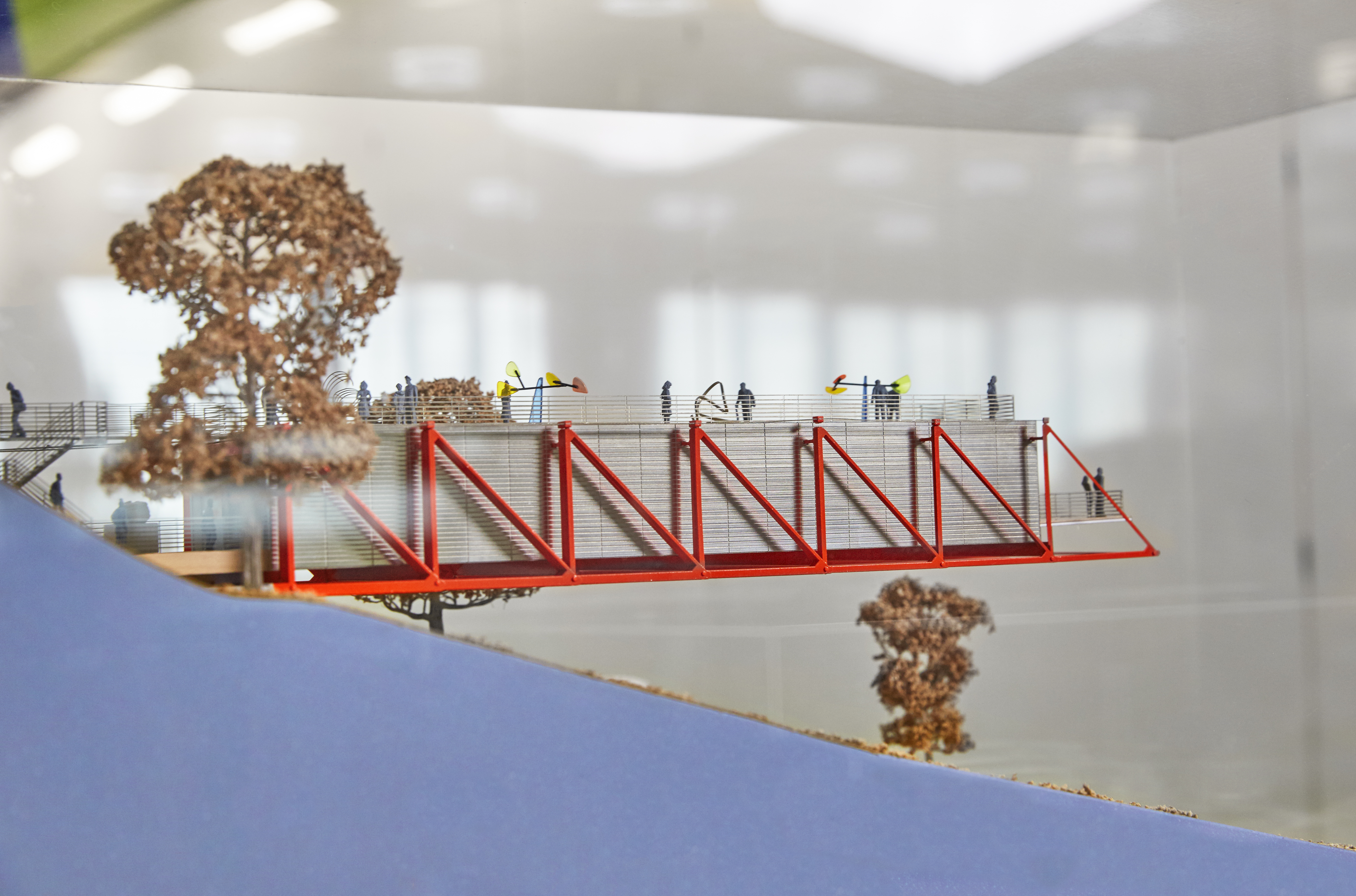

Top: an architectural model of Rogers’ design for the Drawing Gallery at Château La Coste, Provence, France. Below: the finished gallery, 24 metres long and anchored to a ridge by galvanised steel rods so it appears to hover over the slope.

22 Parkside in Wimbledon, London, designed by Richard Rogers and his then wife, Su Rogers (née Bramwell), as a home for Rogers’ parents William Nino Rogers and Dada Rogers. Completed in 1968-70, the house was donated to the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 2015. courtesy of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano’s Centre Pompidou, completed in 1977. courtesy of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

Lloyd’s of London, designed by Richard Rogers and completed in 1986. The steeple of St Andrew Undershaft can be seen to the left. Lloyd’s was Grade I listed in 2011, the youngest structure to obtain this status. English Heritage describes it as ’universally recognised as one of the key buildings of the modern epoch’. courtesy of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

The trading floor at Lloyd’s of London, designed by Richard Rogers and completed in 1986. The building was designed so that the trading floor could expand or contract, according to the needs of the market, by means of a series of galleries around the central space. Services are banished to the perimeter. courtesy of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

The Millenium Dome, London by the Richard Rogers Partnership, completed in 1999. Its twelve masts are intended to be perceved as great arms, outstretched in celebration. courtesy of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

The check-in hall at the Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners-designed Terminal 5 at London Heathrow Airport. The terminal offers an unencumbered, long-span ‘envelope’ – developed with Arup – with a flexibility of internal space conceptually similar to that of the Centre Pompidou. courtesy of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

Three World Trade Center by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, borders 9/11 Memorial Park and is flanked by Santiago Calatrava’s World Trade Center Transit Hub and Fumihiko Maki’s Four World Trade Center. courtesy of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

Three World Trade Center by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, as viewed from 9/11 Memorial Park. The stepped profile accentuates the building’s verticality, relative to the memorial site and is sympathetic to the height and position of the neighbouring buildings. courtesy of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

Richard Rogers (middle) with architects Graham Stirk (left) and Ivan Harbour (right), in their offices on the 14th floor of the Leadenhall Building, a 50-storey tower in the City of London designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners and completed in 2014. for the November 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*224), on the occasion of RSHP’s 10th anniversary

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

Jeweller Ara Vartanian and rapper Swizz Beatz team up on a fusion of spiky silhouettes, sculptural forms and seductive gems

Jeweller Ara Vartanian and rapper Swizz Beatz team up on a fusion of spiky silhouettes, sculptural forms and seductive gemsA pairing that's been in the works since 2019 – and finally we get to see the results

-

The new CLA brings Mercedes's all-electric know-how to a new market sector

The new CLA brings Mercedes's all-electric know-how to a new market sectorMixing high tech moves with tremendous tactile qualities, the buttery smooth new Mercedes-Benz CLA is an electric winner. Wallpaper* drives across Denmark in a triumphant new car with a three-pointed star

-

Collagerie and Zara Home debut perfectly imperfect home accessories

Collagerie and Zara Home debut perfectly imperfect home accessoriesLucinda Chambers’ Collagerie collaborates with Zara Home on a collection that is an ode to the everyday

-

A new London exhibition explores the legacy of Centre Pompidou architect Richard Rogers

A new London exhibition explores the legacy of Centre Pompidou architect Richard Rogers‘Richard Rogers: Talking Buildings’ – opening tomorrow at Sir John Soane’s Museum – examines Rogers’ high-tech icons, which proposed a democratic future for architecture

-

Remembering architect David M Childs (1941-2025) and his New York skyline legacy

Remembering architect David M Childs (1941-2025) and his New York skyline legacyDavid M Childs, a former chairman of architectural powerhouse SOM, has passed away. We celebrate his professional achievements

-

Remembering architect Ricardo Scofidio (1935 – 2025)

Remembering architect Ricardo Scofidio (1935 – 2025)Ricardo Scofidio, seminal architect and co-founder of Diller Scofidio + Renfro, has died, aged 89; we honour his passing and celebrate his life

-

Remembering Christopher Charles Benninger (1942-2024)

Remembering Christopher Charles Benninger (1942-2024)Architect Christopher Charles Benninger has died in Pune, India, at the age of 82; we honour and reflect on his passing

-

East London's disused gasholders are being reinvented

East London's disused gasholders are being reinventedRegent's View by RSHP reinvents a pair of disused gasholders in east London as contemporary residential space and a publically accessible park

-

Remembering Alexandros Tombazis (1939-2024), and the Metabolist architecture of this 1970s eco-pioneer

Remembering Alexandros Tombazis (1939-2024), and the Metabolist architecture of this 1970s eco-pioneerBack in September 2010 (W*138), we explored the legacy and history of Greek architect Alexandros Tombazis, who this month celebrates his 80th birthday.

-

In memoriam: John Miller (1930-2024)

In memoriam: John Miller (1930-2024)We remember John Miller, an accomplished British architect and educator who advocated a quiet but rigorous modernism

-

In memoriam: architect Antoine Predock (1936-2024)

In memoriam: architect Antoine Predock (1936-2024)The late Antoine Predock has left a lasting, international architectural legacy and portfolio, from residential designs to art museums