Glass act: BIG’s Serpentine pavilion and its four summer houses revealed

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Initiated by outgoing gallery director Julia Peyton-Jones, the Serpentine Gallery's programme of pavilion building began at the turn of the century with a tensile structure by the late Zaha Hadid. Sixteen years later, and the pavilion is a highlight of the summer calendar, both in terms of its creative direction and as a venue for events.

This year sees Peyton-Jones' last summer at the Serpentine, and together with artistic director, curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist, she has chosen to go out with a splash, commissioning not just a pavilion on the traditional front lawn location, but also four 'summer houses'. These – sponsored by developers Northacre – are set a short distance away from the gallery, adjoining Queen Caroline's Temple, a classical folly constructed in 1734 and attributed to the progenitor of English Palladianism, William Kent. Bjarke Ingels' BIG takes the credit for the main structure, while the four 25 sq m summer houses are by Kunlé Adeyemi, Barkow Leibinger, Yona Friedman and Asif Khan.

First, the main event. Ingels is a natural choice for this most ephemeral but high profile of buildings. In the past, big players have come rather unstuck when faced with the transient and demountable nature of the pavilion. Oscar Niemeyer's sturdy concrete shell, Jean Nouvel's red plastic shed, or Frank Gehry's hefty construction of timber and steel all seemed to favour statement over function. They were countered by pavilions so diaphanous they barely counted as buildings at all, from Fujimoto's stack to SelgasCano's riot of stretched ribbons and OMA's bulbous inflatable roof.

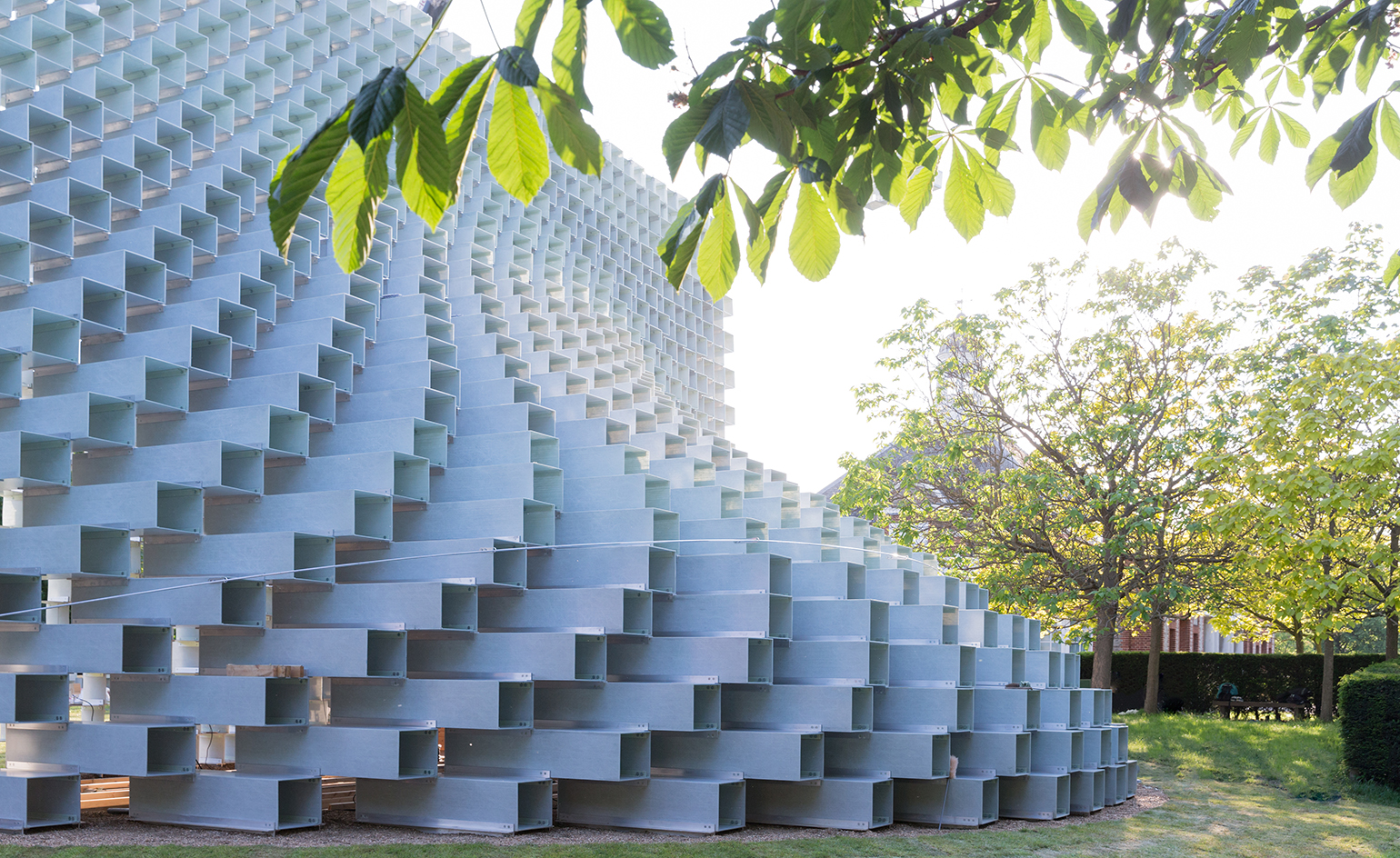

Ingels has an innate understanding of architecture's dramatic potential, and the way in which subtle, repetitive modulations can create a sense of scale and awe. The 2016 pavilion is simplicity itself, built from extruded square tubes of glass fibre, supplied by Fiberline Composites, reinforced and bolted together using hundreds of T-shaped aluminium brackets. This wall of blocks is canted and sloped, rippled and twisted, expanding within to create a cave-like interior, while the exterior 'walls' offer up a slice of man-made landscape in the verdant surroundings.

It is undeniably beautiful, even though the joints and materials are utterly prosaic up close. The sinuous wave of jagged blocks plays games with scale, creating a miniature realisation of the megastructural ziggurats the Danish studio is so adeptly building around the world. As before, the interior space – lined with wood and decked out with simple wooden cube seating – will serve as a café by day and a multi-functional event space by night, with talks, poetry, music, theatre and more. 'There will be no end to experimentation,' Obrist says, paraphrasing Hadid's words to him back in 2000, his acknowledgement of the debt the Serpentine owes her for driving the programme forwards.

Ingels spoke of the project as being a welcome break from the constraints of site and place. 'It's a pure manifestation of the values of the architect,' he says, expounding on the bifurcated functions of the structure. 'It's a wall that becomes a hall, it's a gate but it's open and transparent, or opaque and translucent.' He also cited Jørn Utzon's belief in architecture's ability to create difference from repetition. Above all, Ingels says that the pavilion offers 'unscripted possibilities' to both architect and end users, a rare joy in a world that's becoming more and more unaccustomed to going off-script.

In contrast to the blank slate of the pavilion proper, the four summer house commissions were tasked with taking inspiration from the existing 18th-century folly. This is a little hidden gem, with a cool, stone-flagged and white-washed interior, vermiculated stonework and pared-back detail. The architectural responses are all very different, scattered across the lawns outside in stark opposition to each other.

Frank Barkow was explicit about the prototypical nature of Barkow Leibinger's chunky curved wood extravaganza – 'it has a resonance and will live beyond its four months here', he says. It's countered by Friedman's array of spindly steel cubes, an outdoor exhibition space that looked at the mercy of the elements, even on a calm sunny day. Asif Khan's cool, calm spiky 'temple' is designed to align to the position of the sun on Queen Caroline's birthday, like Kent's original; whereas Kunlé Adeyemi inverted and rotated the interior of the 1734 structure to form a neo-classical object of sandstone and foam, a picturesque pre-fabricated ruin.

The Ingels structure will be rebuilt in both Asia and the US after its sojourn in Kensington Gardens, but the four summer houses will vanish and the landscape return to bucolic splendour. Will this venture set a precedent for the post Peyton-Jones era, ushering in a new era of smaller-scale innovation every summer? Or will the pavilion programme wither without her drive and connections? If it's the latter, the BIG structure is a fitting finale to 16 years of architectural exploration. Today we have a very different relationship with architecture than we did at the turn of the century, and the conjunction of big names and bold forms perhaps no longer dazzles like it once did. Style needs substance, regardless of how temporary a structure is. Ingels delivers both with aplomb.

This wall of blocks is canted and sloped, rippled and twisted; playing with scale and creating a miniature realisation of the megastructural ziggurats the Danish studio is so adeptly building around the world

The base of the structure expands from within to create a cave-like interior, while the exterior 'walls' offer up a slice of man-made landscape in the verdant surroundings

Accompanying the BIG pavilion are four 25 sq m summer houses created by Kunlé Adeyemi, Barkow Leibinger, Yona Friedman and Asif Khan. Pictured: Asif Khan's summer house, designed to catch sunlight reflected from the Serpentine itself

Kunlé Adeyemi’s structure is an inverse replica of Queen Caroline’s Temple, playing with its material space and form to create a new and exciting sculptural object

Yona Friedman's contribution is a flexible modular structure which can be assembled and disassembled in a variety of ways

Frank Barkow was explicit about the prototypical nature of Barkow Leibinger's chunky curved wood extravaganza – 'it has a resonance and will live beyond its four months here', he says

The modern, free-standing structure is constructed from a series of undulating structural bands

INFORMATION

The Serpentine pavilion and summer houses will be open until 9 October. For more information, visit the Serpentine Galleries’ website

ADDRESS

Serpentine Galleries

Kensington Gardens

London, W2 3XA

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.