African brutalism explored: from bold experimentation to uncertain future

Discover the complex and manifold legacies of brutalist architecture in Africa with writer and curator Fabiola Büchele

Brutalism, arguably the easiest architectural language with which to have a love-hate relationship, holds a particularly complex legacy across Africa – welcome to our guide to the continent’s brutalist architecture.

African brutalism: the origins

The movement’s global heyday, from the 1960s to the 1980s, coincided with the independence of many African nations, as they sought to articulate new national identities. Brutalism’s bold experimentation resonated with the optimism of state-building, while its monumental scale conveyed authority and permanence. It seemed a perfect fit for newly independent nations that required educational, financial and healthcare infrastructure, as well as spaces to celebrate culture, history and local heroes.

Mfantsipim School in Cape Coaste, Ghana by Fry, Drew and Partners, 1958 - also included in ’Architecture of Independence: African Modernism’

The history of African Brutalism

This appeal attracted both local architects and planners, some of whom had been educated abroad, and foreign practitioners commissioned by post-colonial governments. The result was a multifaceted body of brutalist architecture, as diverse as the countries in which it was built. The movement’s freedom and experimental character manifested in contextual adaptations such as the use of brise-soleils for shade, thoughtful building orientations and semi-open structures employing ventilation strategies suited to local climates. In some cases, forms and decorative elements drew inspiration from cultural references, further enriching the architectural language.

Yet brutalism carried contradictions. In apartheid South Africa, for example, the style was weaponised as a tool of control. In former Portuguese colonies, where independence came late, much of the brutalist legacy remains entangled with colonial rule. The rapid pace of construction often produced colossal structures that consumed vast resources but failed to fulfil their intended functions. Reflecting colonial hierarchies, international architects frequently secured opportunities to design brutalist buildings across Africa, whereas African architects rarely enjoyed similar prospects abroad. More troubling still, many local architects who shaped the distinctive features of African brutalism remain largely unknown.

A post shared by African Modernism (@african_brutalism)

A photo posted by on

Today, this eclectic legacy stands at a crossroads. Weathered by neglect, expensive to maintain and often cheaper to demolish than restore, these buildings nonetheless serve as markers of a historic period deserving of study and preservation. Renewed interest and critical re-evaluation could transform these monuments into contemporary assets, securing their place in both global and local architectural discourse. They hold significant potential for adaptive reuse and offer lessons in contextual design that merit documentation and conservation.

The following selection provides only a glimpse of the diverse typologies, ambitions and local conditions that shaped the presence of brutalism in Africa.

Examples and typologies

THE BANK: BOAD, Togo

The BOAD, the West African Development Bank building in Lomé, featured in ‘Architecture Encounters’ (Les Rencontres Architecturales de Lomé), the conference taking place in 2024 in Togo

Where: Lomé, Togo

Architect: DMT Architectes (Guy Durand, Philippe Ménard & Gerald Thibault) & Raphaël Ekoué Hagbonon

Construction: 1978-1980

Status: In use

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

A cluster of modernist banks dominates Lomé’s downtown, serving as a striking reminder of the country’s pivotal role in shaping the West African financial sector. Among these, the headquarters of the West African Development Bank (BOAD) stands out for its distinctive architectural language. Its design, which is a collection of domed buildings connected by linear elements, draws inspiration from the compounds of the Tatas Tamberma, an indigenous clay architecture found in northern Togo and neighbouring regions, reflecting a broader trend within Togolese modernism to incorporate local cultural references.

Notably, this cultural dialogue is credited to Togolese architect Raphaël Ekué Hagbonon, who collaborated with the French architectural team commissioned for the project. The BOAD building also represents an uncommon commitment by its owners to the structure’s longevity. The bank maintains a dedicated conservation office, an architectural archive and even a stockpile of the German-made tiles that clad its façade, ensuring that repair and maintenance remain possible well into the future.

THE UNIVERSITY: Obafemi Awolowo University (formerly Ife University), Nigeria

In 2019, a documentary titled Scenes focuses and celebrates the Obafemi Awolowo University in Nigeria

Where: Ife-Ife, Nigeria

Architect: Arieh Sharon

Construction: 1963-1980

Status: In use, with plans for restoration

One of the most significant dimensions of post-colonial freedom was the creation of educational infrastructure. Many universities established during this period remain in use today. In Nigeria, especially, higher education expanded rapidly after independence in 1960, with the country boasting five universities by 1962. These campuses became crucial spaces for intellectual debate on post-colonial priorities and identities.

Among the most notable examples is Ife University, now Obafemi Awolowo University, designed by Bauhaus-trained Israeli architect Arieh Sharon. He was later joined by his son, Eldar Sharon, and Nigerian architect Augustine Akhuemokhan Egbor. Constructed in phases over nearly two decades, the campus features an exceptional collection of climate-responsive buildings that embody the hallmarks of modernism: reinforced concrete, flat roofs and stark linear forms.

Today, the campus is recognised as part of the Bauhaus international heritage, with a transdisciplinary team working to ensure its conservation.

THE MULTI-USE COMPLEX: La Pyramide, Ivory Coast

A post shared by Architectural and arts heritage of Côte d'Ivoire (@paaciv)

A photo posted by on

Where: Abidjan, Ivory Coast

Architect: Rinaldo Olivieri

Construction: 1968-1973

Status: Abandoned

Conceived with exuberant optimism, the multipurpose high-rise La Pyramide now stands as an empty monument to some of the unfulfilled ambitions of modernist architecture. Designed by an Italian architect, the building takes the form of a pyramid with a concrete tower rising from its core. It was among the earliest high-rises of its era, incorporating apartments and offices on the upper levels and retail space at its base.

Constructed over five years during the late 1960s and early 1970s, it soon became evident that the design was ill-suited to its intended function. Signs of deterioration appeared before the building had even reached its twentieth year. Yet its allure persists. The skeletal frame of La Pyramide remains one of Africa’s most recognisable modernist landmarks. Although the Ivorian government announced plans to renovate the structure more than a decade ago, these have yet to materialise, leaving the building as a stark reminder of brutalism’s less successful, yet beloved experiments and an uncertain future.

THE HOTEL: Hotel du Lac, Tunisia

Where: Tunis, Tunisia

Architect: Raffaele Contigiani

Construction: 1970-1973

Status: Abandoned

The construction of large-scale luxury hotels in the 1970s reflected the era’s optimism for tourism and commerce, making this one of the most widespread brutalist typologies across many African nations. Among these is the Hôtel du Lac, an inverted pyramid whose top floor extends to nearly twice the length of its ground floor. Its structure combines exposed concrete slabs with a steel framework, a striking expression of the style’s boldness.

Abandoned since 2000, the building’s future remains uncertain. Yet even in its ruinous state, it endures as one of the most recognised brutalist landmarks in Africa. In Tunis, its prominent downtown location makes it a contested icon, while for its late Italian architect, it stands as the only memorable work by which he is remembered.

THE CINEMA: Cinema Studio Namibe, Angola

Cinema Studio Namibe in Angola is on the World Monuments Fund endangered buildings 2025 Watch

Where: Moçâmedes

Architect: José Botelho Pereira

Construction: 1973

Status: Abandoned

Across the African continent, cinemas form a fascinating architectural legacy, reflecting their central role in the flourishing pan-African film industry of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. In former Portuguese colonies, however, independence came only in the mid-1970s, a fact that shaped the modernist heritage of these nations. Many buildings from this period were still commissioned by the colonial administration, often serving political rather than cultural ambitions.

The Cinema Studio Namibe, resembling a vast concrete saucer, exemplifies this trend. Conceived as part of the Portuguese regime’s effort to use cinemas as propaganda tools, its construction began in 1973. Work progressed to the completion of a semi-enclosed dome designed for natural ventilation and filtered sunlight, enclosing a main theatre planned to accommodate around 400 people. However, construction came to an abrupt halt following Angolan independence in 1975.

Today, the unfinished structure remains an eccentric landmark, a reminder of how political upheaval can shape and interrupt architectural visions.

THE MONUMENT: Cinema Roundabout, Burkina Faso

A post shared by African Modernism (@african_brutalism)

A photo posted by on

Where: Ouagadougou

Architect: Ali Fao & Ignace Sawadogo

Construction: 1986-1987

Status: intact

The brutalist design language and liberal use of concrete are also evident in numerous monuments across the African continent, commemorating different facets of post-independence nation-building. One of the most distinctive and enduring examples is the Place des Cinéastes (Filmmakers’ Square) in Ouagadougou. Standing just over 12m tall, it offers a strikingly literal tribute to the pan-African filmmakers celebrated at FESPACO, Burkina Faso’s long-running film festival, which was a cornerstone of Thomas Sankara’s efforts to strengthen Burkina Faso’s decolonisation efforts.

The design evokes a stack of camera lenses and film reels, which were the essential tools of the craft at the time, and emerged from a public competition won by architect Ali Fao and city planner Ignace Sawadogo.

THE INSTITUTIONAL BUILDING: Kenyatta International Conference Centre, Kenya

The Kenyatta centre will play host to the first Pan-African architecture biennale, to take place in Nairobi in 2026;

Where: Nairobi

Architect: Karl Henrik Nøstvik and David Mutiso

Construction: 1967-1973

Status: partially in use

Still in active use today, the Kenyatta International Conference Centre (KICC) was commissioned by its namesake, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, Kenya’s first president after independence. Designed by Norwegian architect Karl Henrik Nøstvik in collaboration with Kenyan architect David Mutiso, the complex is organised around a cylindrical 32-storey tower. Beside it stands an amphitheatre crowned with a conical roof, a gesture that references traditional rural forms. Inside, a retro-futuristic assembly hall unfolds, characterised by an intricate interplay of angular lines and expansive spaces.

Since its inauguration in 1973, the KICC has remained a central venue for political and cultural life, hosting numerous historically significant symposia, conferences and congresses and thus realising its founding vision as an architecture capable of accommodating the ambitions of a newly independent nation. In 2026, it is scheduled to host Africa’s first architectural biennale, a milestone that will further cement its place in the continent’s architectural history.

THE MUSEUM: National Museum of Ethiopia, Ethiopia

Where: Addis Ababa

Architect: Gashaw Beza Tesfamichel

Construction: 1978-1981

As Ethiopia was famously never colonised, brutalism in this context appears more closely linked to the nation’s socialist orientation and the architectural language that often accompanied it. Architect Gasha Beza Tesfamichel, who designed the National Museum, is believed to have studied in former Yugoslavia, where he likely encountered brutalist influences that informed his work in Addis Ababa.

The museum exemplifies the brutalist vocabulary through its use of unvarnished concrete and straightforward, rectilinear forms. This severity is softened by a vibrant mural by the late Ethiopian artist Afewerk Tekle, depicting some of the museum’s most celebrated artefacts. Positioned above the main entrance, the mural spans the two upper storeys, introducing a vivid cultural narrative to the otherwise austere façade.

Although relatively unassuming and easily overlooked, the museum remains a significant example of how architecture can reflect a nation’s political trajectory and aspirations.

Fabiola Büchele is an Austrian writer and curator based between Berlin and Lomé. She studied Journalism and International Relations in London and Auckland. She spent five years working as a freelancer in Vietnam, followed by time in Tunis working for the Kamel Lazaar Foundation before joining Studio Francis Kéré as their Creative Director in charge of exhibitions and publications during the firm’s Pritzker-Prize winning tenure. In 2023, she co-founded the architecture, design and research studio Studio NEiDA. In 2025, the studio was commissioned to curate Togo’s first national pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale as well as the country’s first participation at the Triennale Milano International Exhibition.

-

John Costi interrogates his fractured psyche with new Somerset House show ‘Bapou’s Bubbles’

John Costi interrogates his fractured psyche with new Somerset House show ‘Bapou’s Bubbles’The artist discovered his creativity while imprisoned for armed robbery. Now, he’s hosting a surreal performance piece that speaks to the healing power of art

-

Europe’s auto industry regroups at the Brussels Motor Show: what’s new and notable for 2026

Europe’s auto industry regroups at the Brussels Motor Show: what’s new and notable for 20262026’s 102nd Brussels Motor Show played host to a number of new cars and concepts, catapulting this lesser-known expo into our sightlines

-

Wallpaper* Best Use of Material 2026: Beit Bin Nouh, Saudi Arabia, by Shahira Fahmy

Wallpaper* Best Use of Material 2026: Beit Bin Nouh, Saudi Arabia, by Shahira FahmyBeit Bin Nouh by Shahira Fahmy is a captivating rebirth of a traditional mud brick home in AlUla, Saudi Arabia - which won it a place in our trio of Best Use of Material winners at the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2026

-

In addition to brutalist buildings, Alison Smithson designed some of the most creative Christmas cards we've seen

In addition to brutalist buildings, Alison Smithson designed some of the most creative Christmas cards we've seenThe architect’s collection of season’s greetings is on show at the Roca London Gallery, just in time for the holidays

-

Richard Seifert's London: 'Urban, modern and bombastically brutalist'

Richard Seifert's London: 'Urban, modern and bombastically brutalist'London is full of Richard Seifert buildings, sprinkled with the 20th-century architect's magic and uncompromising style; here, we explore his prolific and, at times, controversial career

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthFrom Malibu beach pads to cosy cabins blanketed in snow, Wallpaper* has featured some incredible homes this month. We profile our favourites below

-

A neo-brutalist villa for an extended family elevates a Geneva suburb

A neo-brutalist villa for an extended family elevates a Geneva suburbLacroix Chessex Architectes pair cost-conscious concrete construction with rigorous details and spatial playfulness in this new villa near Geneva

-

Cascading greenery softens the brutalist façade of this Hyderabad home

Cascading greenery softens the brutalist façade of this Hyderabad homeThe monolithic shell of this home evokes a familiar brutalist narrative, but designer 23 Degrees Design Shift softens the aesthetic by shrouding Antriya in lush planting

-

Spice up the weekly shop at Mallorca’s brutalist supermarket

Spice up the weekly shop at Mallorca’s brutalist supermarketIn this brutalist supermarket, through the use of raw concrete, monolithic forms and modular elements, designer Minimal Studio hints at a critique of consumer culture

-

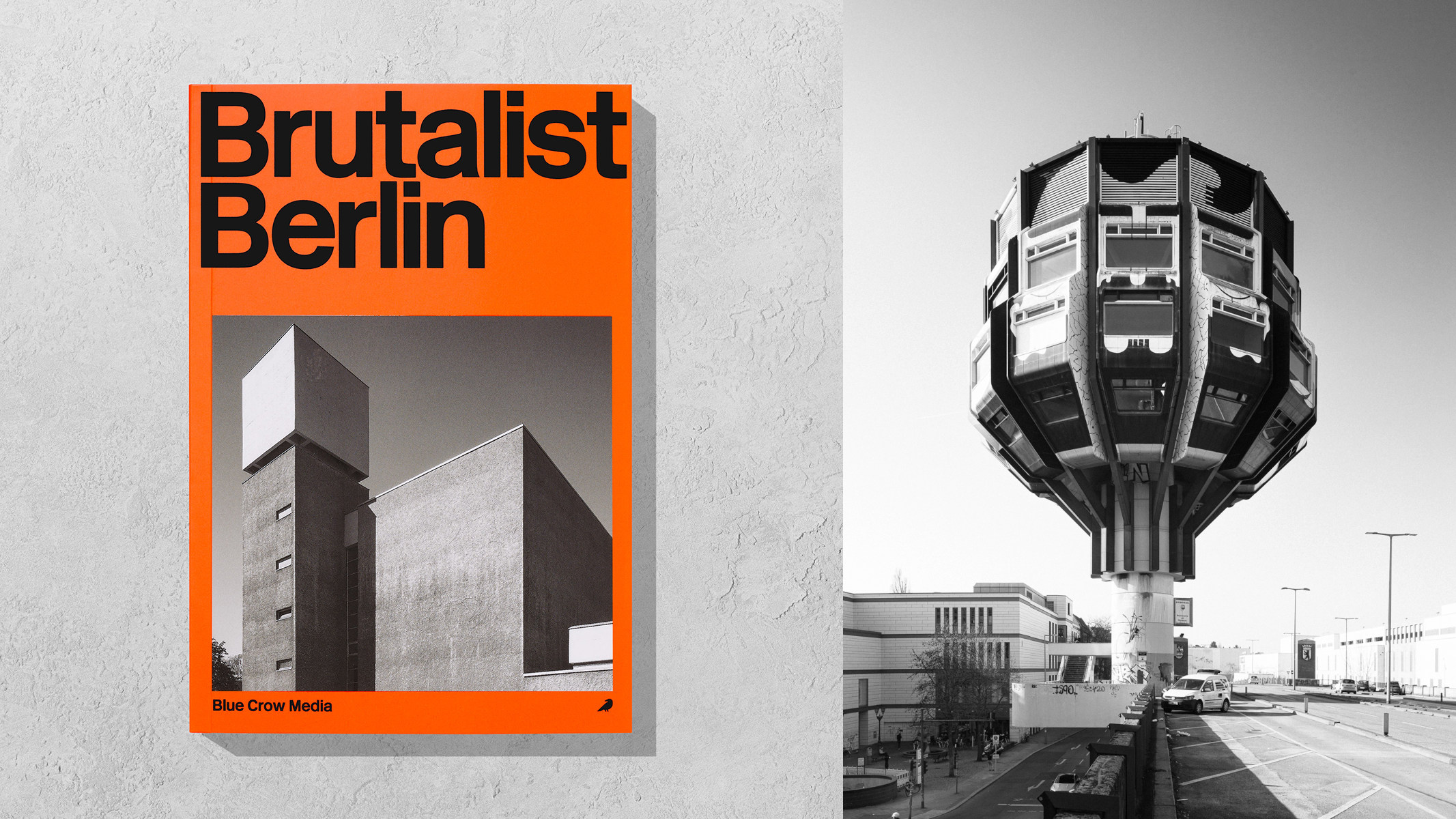

‘Brutalist Berlin’ is an essential new guide for architectural tourists heading to the city

‘Brutalist Berlin’ is an essential new guide for architectural tourists heading to the cityBlue Crow Media’s ‘Brutalist Berlin’ unveils fifty of the German capital’s most significant concrete structures and places them in their historical context

-

Celebrate the angular joys of 'Brutal Scotland', a new book from Simon Phipps

Celebrate the angular joys of 'Brutal Scotland', a new book from Simon Phipps'Brutal Scotland' chronicles one country’s relationship with concrete; is brutalism an architectural bogeyman or a monument to a lost era of aspirational community design?