Decode: Julius Popp interview

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

A new digital and interactive design exhibition opens at the V&A today in London entitled Decode: Digital Design Sensations. Curated in collaboration with the digital arts organisation onedotzero, the centrepiece of the exhibition will be a huge new installation in the museum’s Grand Entrance by a young German called Julius Popp who is currently turning heads in the digital art world.

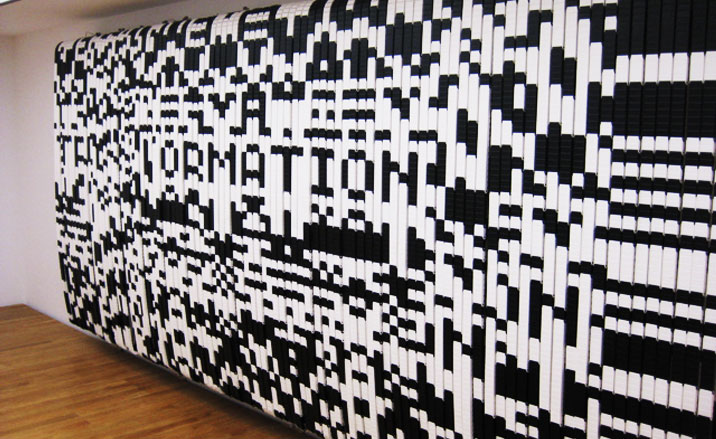

Entitled Bit.Code, the piece is a large mechanically operated ‘screen’ consisting of identical rotating black and white tracks made up of the 1s and 0s of basic binary digital code. Controlled by a specially designed software, the tracks will rotate individually, pausing at regular intervals to display the most frequently used key words taken from recent web feeds of current news sites.

We went to visit Popp in his home town of Leipzig where he was hard at work putting the finishing touches to the Bit.Code prototype to ask him about his work and the motivation behind it.

Julius, your work is divided into categories can you explain a bit more about them?

JP: There are different series in my work. There is the ‘Micro’ series and the ‘Bit’ series, for example. The Micro series investigates human cognitive adaptation processes and the Bit series creates metaphors for them. So in a project such as Micro.Flow and Bit.Flow, for example, Micro.Flow examines how information [on the Internet] is presented and changes, how it is created and then dissipates and at what point in time we are able to absorb it. Bit.Flow is about creating a suitable visual metaphor to represent this.

What is the thinking that underscores these works?

There is a Greek legend that concerns a thread that Ariadne gives to Theseus to help him find his way out of the Minotaur’s labyrinth. The philosophers Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze talked about how this thread has been broken in modern times in that there is no single way out anymore because everything happens simultaneously. Bit.Flow represents the fact that there is now a different kind of navigation and orientation in our culture.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Bit.Flow is a machine that represents this flow of information with immiscible coloured and transparent liquids moving through tubes which allows us to recognise letters and words formed for short periods of time. Perhaps your best-known work, Bit:Fall, is a rather spectacular curtain of water drops that form into words as they fall. Tell us about your new work Bit.Code and how it differs from Bit:Fall.

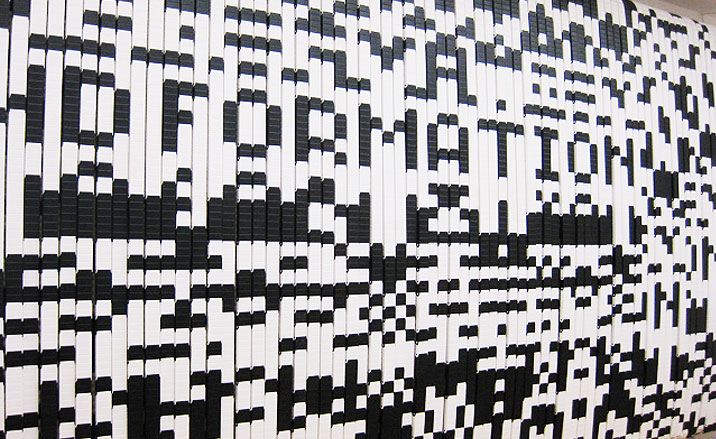

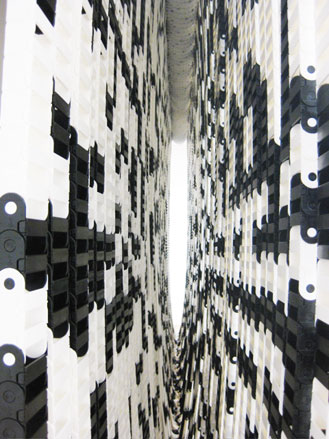

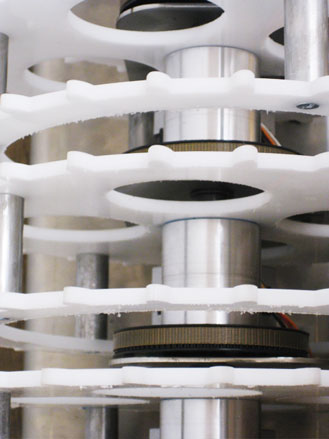

JP: What both works have in common is that they deal with ‘bits’, these are represented in Bit.Fall by single drops of water, in Bit.Code they are plastic chain links that are either white or black. Both represent information but in quite different ways. With the waterfall, a machine generates a readable word for a very short moment in time that falls down and falls apart. Bit.Code has 96 plastic chains, each with the same black and white code, or pixels constellations. There is a limited number of pixels that can be moved next to each other. When they move, words are created and when they move again, new words appear. It is a limited system with the capacity to represent an almost unlimited variety of information.

That sounds like an analogy for DNA: a limited number of code units with almost unlimited potential for recombination.

JP: Yes, this is one aspect, the other is that we as humans are only capable of reading and interpreting the letters of the alphabet, but in reality the code of the chains is like a barcode. For a machine, every part of this barcode is readable, for us it is just noise or random patterns. We can only deal with information that we have been taught or trained to read.

Does that mean you are translating this input code into something that is readable for us?

JP: I arrange these chains into something that is readable; that is, I arrange the system into an intelligible one.

Just like a computer does right? Information arrives as binary impulses and is arranged by the computer back into legible words and images on screen

JP: Exactly

Aren’t you just making different kinds of computers in a way?

JP: It is hard to call them that. They are screens and they are systems or computing machines at the same time. With the waterfall for example, you can see it simply as a screen, but on the other it is representing the decay of what is shown there. Just like with Bit.Code it is also about the changing processes within our culture. About the generation of new values from a limit number of parts.

So you are using mechanical means to translate a digital phenomenon that usually remains invisible to us. Are you trying to make this enormous, coded world of the Internet more transparent?

JP: I am not primarily interested in the technology that we have developed to communicate, I am interested in the cultural changes that are happening as a result. Expressing how we interact with information, how we use it and the influence it has on us in a visual form is more important to me than the technology behind it.

So you are concerned with the nature of the information that this digital system is feeding us and our lack of criticism about what information we consume?

My work is about reflections and the drawing of conclusions. We need to reflect more on what information we are actually being fed with. One of my works deals with listing the twelve most frequent key words that turn up in news feeds each day over a certain time period. It begs the question: Is that really all that moves us or affects us as a society?

Because our ‘news’ information is so heavily filtered?

JP: Because it is so heavily filtered and so short-lived. I have also made graphic illustrations of the half-lives of certain pieces of information, asking: how long is the attention span for a piece of news, how long do the news agencies propagate it for, how long do newspapers print it? Does it depend on whether our neurones are saturated with it and we don’t want to hear about it anymore? Or does it lie with the media propagators: By dwelling longer on a particular theme is a newspaper more interested in securing its own existence and circulation or having a sustained influence on society?

You come from an art background but are working in highly scientific fields. Explain to us the difference between the two facets and how you reconcile them.

As an artist I am not actually bound to formulate the truth, I am allowed to formulate theories that do not necessarily have to be true. this gives me a certain freedom that a scientist does not have. I can move and express myself much more freely in certain areas. basically though, I am driven by similar principles, namely finding paradigms and explanations for processes that are unknown to us.

How are the words for your pieces selected?

JP: I just build structures and these structures choose the words – I have no influence on what comes out. A statistical algorithm evaluates and selects the words. I an not interested in the individual values – only in the flow and the changes. I do not want to tell any stories, I want to point to the overlying structures and make them visual. For the Bit pieces, a program reads Google news, for example and then counts the incidence of every word. Very common words, that come up 10-15 times in a piece like ‘if’, ‘the’, ‘and’ etc. are discarded because they are irrelevant. Other words like ‘must’ and ‘go’ also get filtered out. Words that come up 2-10 times are the ones that carry meaning. For this new project I am working in collaboration with software experts from SAP who are helping me improve the selection capability. At the moment I am only working with mainstream media sites. What would be important is to compare these with personal opinion as found in blogs or twitter for example, on a global as well as local scale. To build a cultural data landscape from that – where information comes from, where it goes etc. – would be extremely interesting. We have very little knowledge about how much power information really has.

You were born and grew up and studied in Leipzig which is a relatively small city but with a big artistic reputation. Why did you decide to stay here and not move on?

JP: I stay here because it has the right mix of calm and debate. It doesn’t distract me too much from what I want to do and I have built up an infrastructure here over the last five years that I would not find so easily and quickly anywhere else; which means I simply cannot leave.

Do you think that the advent of the Internet has negated the need to travel for the acquisition of information?

JP: When I travel somewhere then my perception is not restricted. I smell, hear and experience things that the Internet simply cannot offer. There is a large qualitative difference in the way things are perceived. Also, the Internet displays a very selective content. This has of course been collected, organised and structured by society but it still offers only very specific procedures – or words. It cannot replace the reality of experiencing a foreign culture.

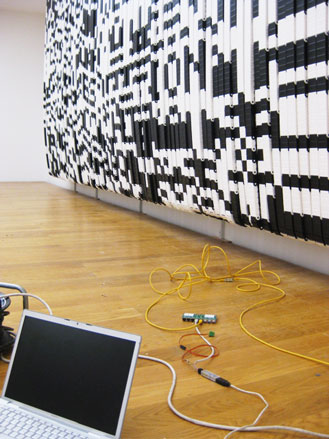

Bit.Code has 96 plastic chains, each with the same black and white code, or pixels constellations. There is a limited number of pixels that can be moved next to each other. When they move, words are created and when they move again, new words appear," explains Popp.

Bit.Code by Julius Popp, in the German designer's studio prior to its installation at the V&A

The piece is a large mechanically operated ‘screen’ consisting of identical rotating black and white tracks made up of the 1s and 0s of basic binary digital code

Plans in hard copy for Bit.Code

The rotating tracks that make up Bit.Code

Daniel Brown, On Growth and Form series, 2009. Decode: Digital Design Installations. Copyright V&A Images.%A

Jason Bruges Studio, Mirror Mirror, 2009, commissioned by V&A and SAP. Decode: Digital Design Installations. Copyright V&A Images.

Julius Popp, bit.code, 2009, commissioned by V&A and SAP. Decode: Digital Design Installations. Copyright V&A Images.

Daan Roosegaarde, Dune, 2006-9. Decode: Digital Design Installations. Copyright V&A Images.

Daniel Rozin, Weave Mirror, 2007. Decode: Digital Design Installations. Copyright V&A Images.

Ross Phillips, Videogrid, 2008. Decode: Digital Design Installations. Copyright V&A Images.

Mehmet Akten, Body Paint, 2009. Decode: Digital Design Installations. Copyright V&A Images.

Sennep/Yoke, Dandelion, 2006-9. Decode: Digital Design Installations. Copyright V&A Images.