Greenland's Qaammat Pavilion for Unesco celebrates land and people

Architect Konstantin Ikonomidis designs Qaammat, a pavilion just above the Arctic Circle in Greenland, that celebrates the local landscape and the Inuit community

Julien Lanoo - Photography

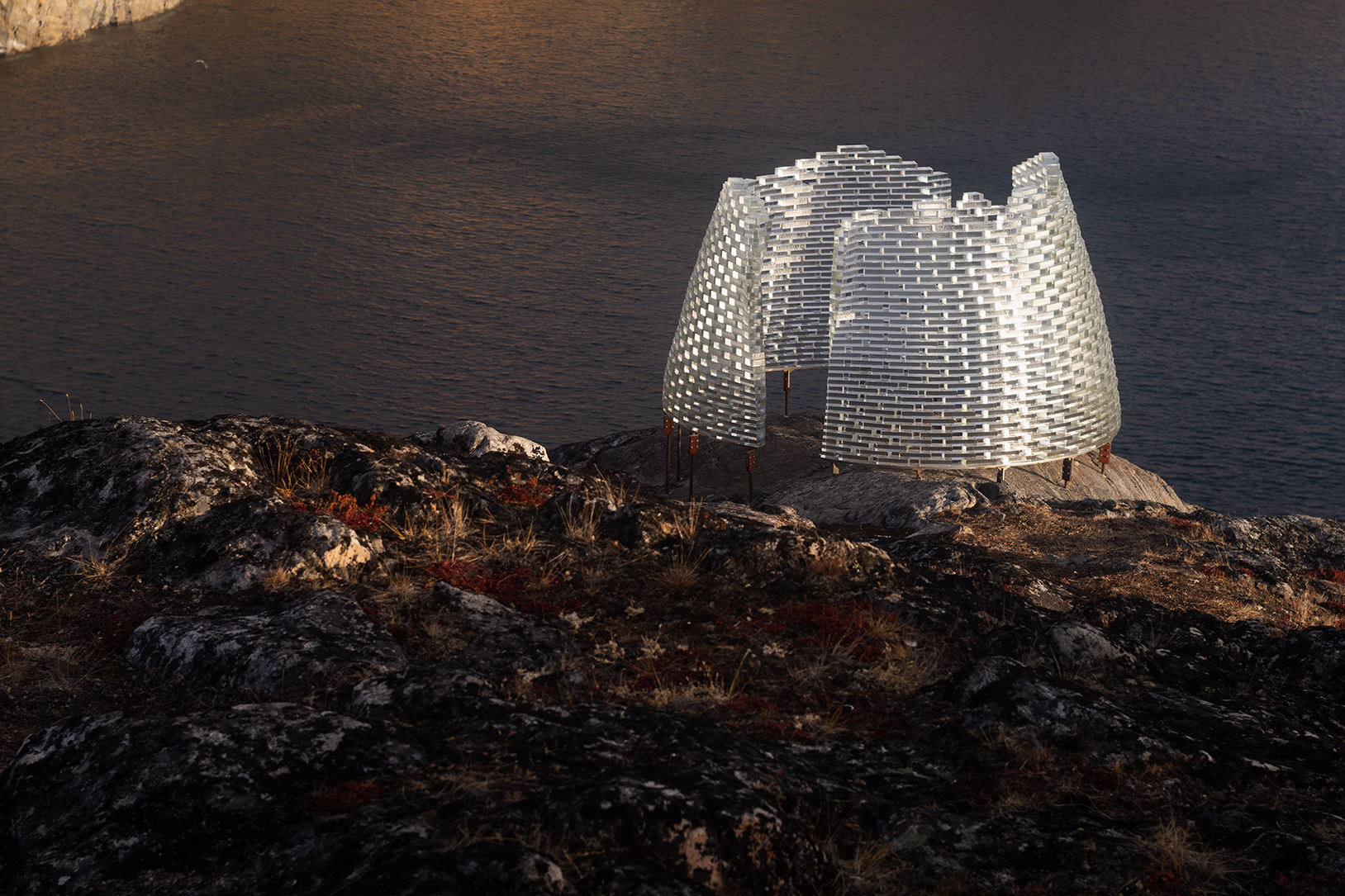

The architect Konstantin Ikonomidis, Swedish but of Greek extraction, is currently stationed in a small museum in Sisimiut, just above the Arctic Circle in Greenland. The view out of his window is as ridiculously perfect as you would imagine it to be, a jumble of brightly coloured pitched-roof houses on a rocky headland of muted grey and green. About an hour’s sail north is the village of Sarfannguit (you pretty much have to fly, sail or dogsled to get anywhere in Greenland). High on a hill above the village, Ikonomidis has just installed Qaammat, two curved walls of glass brick, a kind of striking shelter-come-cairn or permanent ‘pavilion’ as he calls it, for Unesco.

The area around Sarfannguit, stretching from Aasivissuit to Nipisat, was declared a Unesco World Heritage site in 2018, Greenland's third. The new glass pavilion was commissioned by Unesco in 2019, intended as a celebration of the local landscape, cultural as well as physical, and the Inuit community’s connection with that landscape (Greenland is almost 90 per cent Inuit or European-Inuit).

Ikonomidis has been in Greenland since 2017, based in the capital Nuuk before the move to Sisimiut (population 5,600ish), the country’s second city. Fascinated by house building traditions and extreme climates, he considered Greenland fertile ground. ‘I was asked to make some kind of small house for the Nuuk Nordisk Culture Festival and I didn’t want to just make a beautiful house you just walk into and walk out,’ he says. ‘I was trying to go a little bit beyond the obvious.’ Ikonomidis came up with Qamutit, a conceptual sled-house. ‘At the time, I was building a traditional kayak in the Greenlandic style, where you actually tie things together with ropes. And that structure is mostly tied together in the same way.'

Qamutit is essentially timber scaffolding lashed to large skis. Its construction employed other traditional Inuit building techniques, where wooden poles are placed in accurately cut holes instead of bolted or screwed together. This combination of lashing and slotting means that Inuit sleds have enough give and take to survive travelling long distances on ice and snow. Ikonomidis attached Douglas fir panels to the scaffolding poles and visitors were asked to share their thoughts on what makes a house a home, posting them on one of the panels.

‘Unesco had seen the sled house and wanted to collaborate,’ he says, ‘so we visited Sarfannguit to look for a potential site for an installation.’ This time he wanted the work to be fixed and permanent: ‘The budget was really low but it is so beautiful there and I wanted to bring attention to the village.'

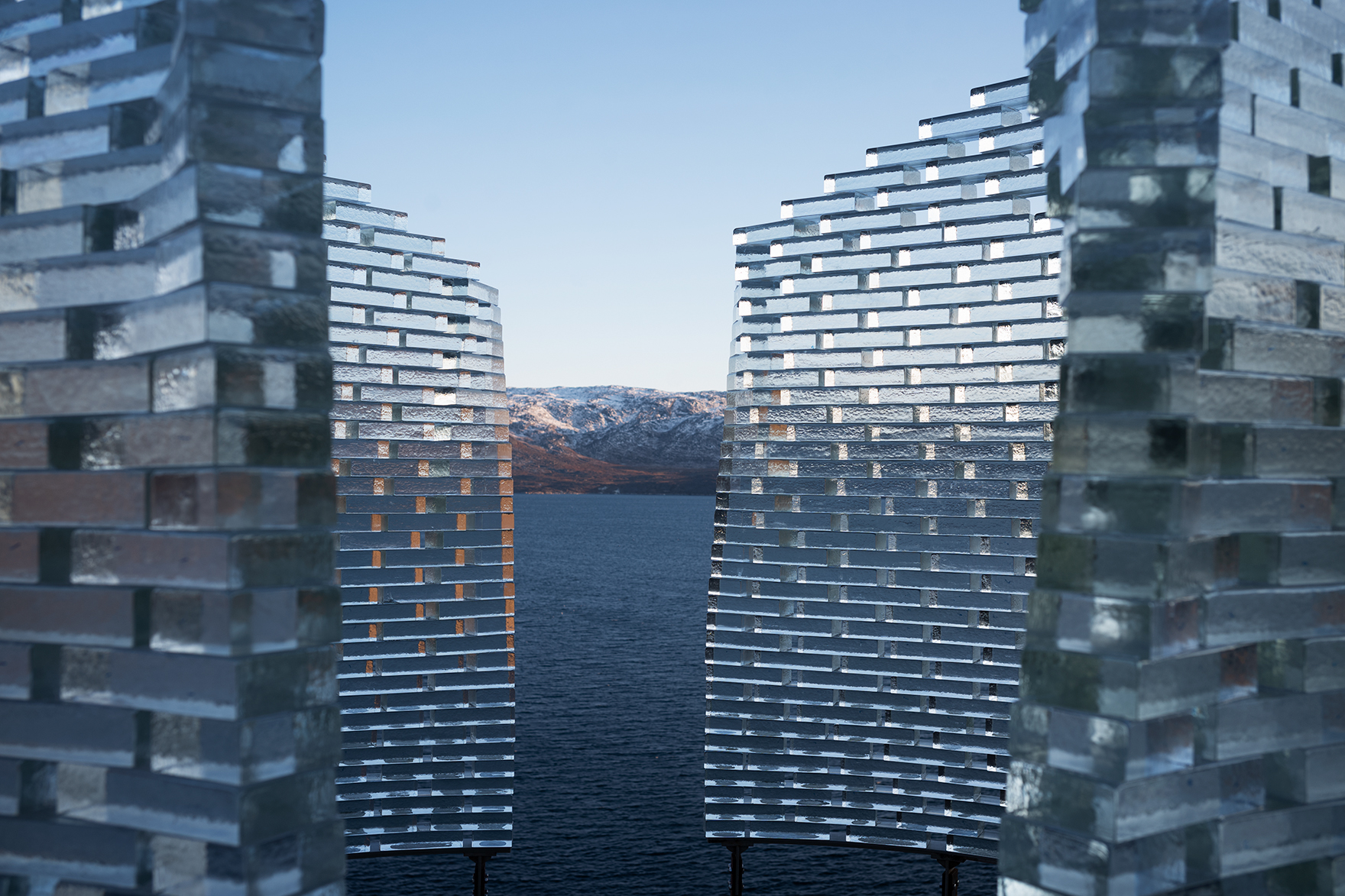

He also wanted to make sure that the work reflected the lives, ideas and traditions of the Sarfannguit residents. ‘I wanted to find out what they wanted,’ says Ikonomidis. ‘I asked them to talk about nature, what it meant to them and what their relationship to it was,’ he says. ‘There is a sense of its power here because everything is oversized, with these big mountains. There is a respect, a sensitivity to it but also a sense of its vulnerability. It’s there in the local mythology. And then I came up with the idea of using glass. It had that sensitivity and vulnerability, a contrast with the rock. And of course you also get the reflections and the play with light, and it looks like ice. It was a win-win.’

The pavilion’s undulating walls are made up of five tons of opaque glass bricks attached to metal poles, sunk into rock, a method borrowed from local house building traditions. The two walls have two narrow openings, allowing for a kind of intimacy and exposure at the same time.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

As Ikonomidis says, the experience of being in or around the pavilion is different depending on the weather or what season or time of day you are there. ‘I was actually surprised by how much it changes,' he says. ‘Even if I look at photographs now, I can categorise them by the time of day they were shot. Sometimes it appears blue, sometimes it is yellow. And when you walk around it, it can become almost transparent, from other angles very textured, sometimes it seems to absorb light and other times to reflect it.'

With a population of 100, Sarfannguit is, in Greenland terms, large and thriving. Many of the country’s smaller villages lie abandoned and in ruins. The industrialisation of fishing and the Danish Government's policy of relocating villagers to larger towns, particularly the capital Nuuk, has left Greenland littered with ghost villages. Indeed, Sarfannguit is the only active village left in the new Unesco Heritage area and there is an abandoned village nearby. Ikonomidis imagines his pavilion as a connection between the two outposts, between the past and the present. It is also intended to be a waymaker or beacon on a planned hiking trail between Sarfannguit and Nipisat, an extension to the existing Arctic Circle Trail and another way of drawing attention and visitors to the village.

Now that the Qaammat project is done, Ikonomidis is preparing to head to Tanzania. He worked in the country before moving to Greenland, developing a housing prototype that would help stop the spread of malaria. He’s going to rejoin his old team and work on bamboo housing designs, while also pursuing what he calls his ‘art/architecture projects’.

It’s hard to imagine, though, that he won’t be back in Sarfannguit, checking in on his hilltop monument to the village and the community it maintains. ‘They have been involved since the very beginning and they were there when the pallets of glass bricks arrived,’ he says. ‘They are really happy with the pavilion and that is the most valuable thing to me.'

INFORMATION

- Julien Lanoo - PhotographyPhotographer

-

Five of the finest compact cameras available today

Five of the finest compact cameras available todayPocketable cameras are having a moment. We’ve assembled a set of cutting-edge compacts that’ll free you from the ubiquity of smartphone photography and help focus your image making

-

London label Wed Studio is embracing ‘oddness’ when it comes to bridal dressing

London label Wed Studio is embracing ‘oddness’ when it comes to bridal dressingThe in-the-know choice for fashion-discerning brides, Wed Studio’s latest collection explores the idea that garments can hold emotions – a reflection of designers Amy Trinh and Evan Phillips’ increasingly experimental approach

-

Arts institution Pivô breathes new life into neglected Lina Bo Bardi building in Bahia

Arts institution Pivô breathes new life into neglected Lina Bo Bardi building in BahiaNon-profit cultural institution Pivô is reactivating a Lina Bo Bardi landmark in Salvador da Bahia in a bid to foster artistic dialogue and community engagement

-

Doshi Retreat at the Vitra Campus is both a ‘first’ and a ‘last’ for the great Balkrishna Doshi

Doshi Retreat at the Vitra Campus is both a ‘first’ and a ‘last’ for the great Balkrishna DoshiDoshi Retreat opens at the Vitra campus, honouring the Indian modernist’s enduring legacy and joining the Swiss design company’s existing, fascinating collection of pavilions, displays and gardens

-

Rains Amsterdam is slick and cocooning – a ‘store of the future’

Rains Amsterdam is slick and cocooning – a ‘store of the future’Danish lifestyle brand Rains opens its first Amsterdam flagship, marking its refined approach with a fresh flagship interior designed by Stamuli

-

Three lesser-known Danish modernist houses track the country’s 20th-century architecture

Three lesser-known Danish modernist houses track the country’s 20th-century architectureWe visit three Danish modernist houses with writer, curator and architecture historian Adam Štěch, a delve into lower-profile examples of the country’s rich 20th-century legacy

-

Is slowing down the answer to our ecological challenges? Copenhagen Architecture Biennial 2025 thinks so

Is slowing down the answer to our ecological challenges? Copenhagen Architecture Biennial 2025 thinks soCopenhagen’s inaugural Architecture Biennial, themed 'Slow Down', is open to visitors, discussing the world's ‘Great Acceleration’

-

This cathedral-like health centre in Copenhagen aims to boost wellbeing, empowering its users

This cathedral-like health centre in Copenhagen aims to boost wellbeing, empowering its usersDanish studio Dorte Mandrup's new Centre for Health in Copenhagen is a new phase in the evolution of Dem Gamles By, a historic care-focused district

-

This tiny church in Denmark is a fresh take on sacred space

This tiny church in Denmark is a fresh take on sacred spaceTiny Church Tolvkanten by Julius Nielsen and Dinesen unifies tradition with modernity in its raw and simple design, demonstrating how the church can remain relevant today

-

Slides, clouds and a box of presents: it’s the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s quirky new pavilion

Slides, clouds and a box of presents: it’s the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s quirky new pavilionAt the Dulwich Picture Gallery in south London, ArtPlay Pavilion by Carmody Groarke and a rich Sculpture Garden open, fusing culture and fun for young audiences

-

‘Stone, timber, silence, wind’: welcome to SMK Thy, the National Gallery of Denmark expansion

‘Stone, timber, silence, wind’: welcome to SMK Thy, the National Gallery of Denmark expansionA new branch of SMK, the National Gallery of Denmark, opens in a tiny hamlet in the northern part of Jutland; welcome to architecture studio Reiulf Ramstad's masterful redesign of a neglected complex of agricultural buildings into a world-class – and beautifully local – art hub