Polyvilla: Palladian paradigms at the RIBA

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

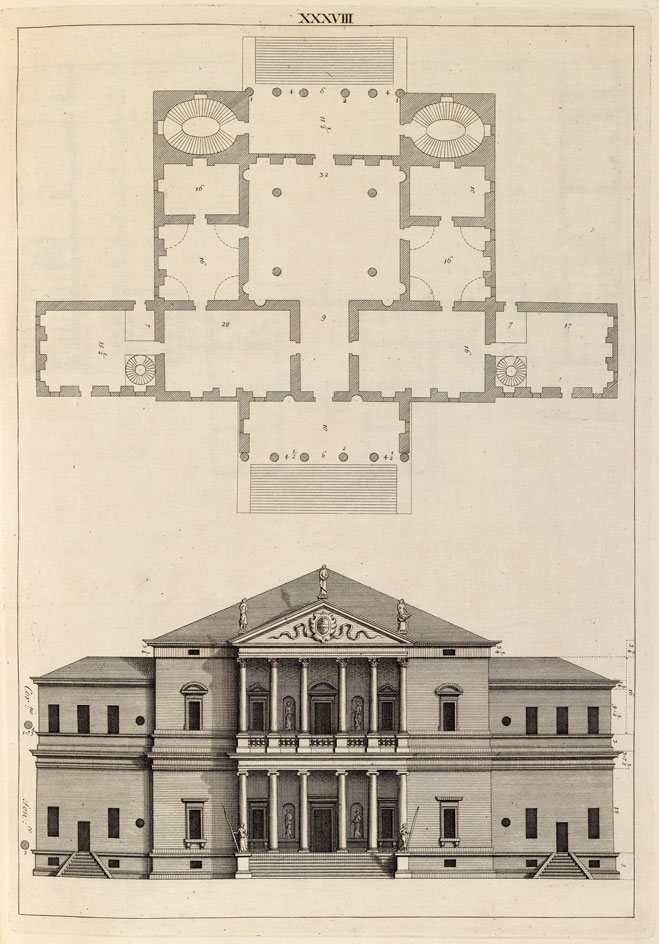

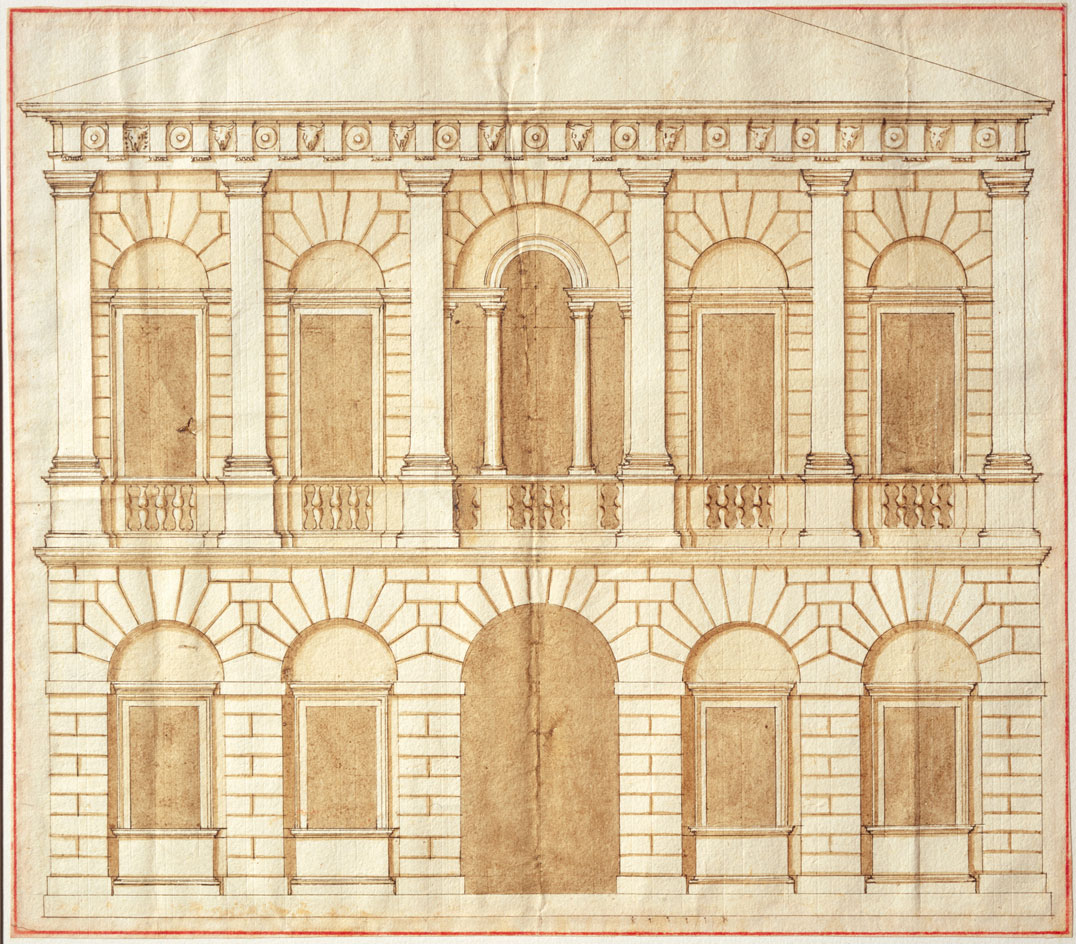

An exhibition entitled 'Palladian Design: The Good, the Bad and the Unexpected' might not, at first glance, sound very Wallpaper*, but this cunningly curated little show at the RIBA is a reminder that the 16th-century Italian architect's influence is very much alive and kicking. Though it kicks off in historic mode with a selection from the RIBA's superb collection of Palladio's original drawings, it rapidly moves on to England, where the Palladian style was adopted (and adapted) first by Inigo Jones and then a host of well-heeled architectural followers – including James Gibbs, whose design for St Martin's in the Fields in London is represented by its original 1721 wooden model, easily the most striking exhibit in the show.

A century later and Palladio's influence becomes harder to detect, and the co-curators, Charles Hind and Vicky Wilson, have to resort to a few intellectual contortions to make 19th-century neoclassicism sound even faintly Palladian; most of the buildings they reference certainly don't look it. Ironically they seem on surer ground when they come to look closer to the present day. The modern rediscovery of Palladian principles ranges from Gunnar Asplund's imaginative Lister County Courthouse from 1919 to the laboured forelock-tugging of Raymond Erith and Quinlan Terry, and from Oswald Ungers' convincingly Palladian Glashütte to Stephen Taylor's tongue-in-cheek cowshed, but the sheer range of contemporary responses strongly suggests that the prominent Paduan's influence still has plenty of puff in it.

Myriad modern designs subtly (and not so subtly) reference Palladio's original architectural tropes. Pictured: Lister County Courthouse, Sölvesborg, Sweden, by Erik Gunnar Asplund, 1919.

The show kicks off in historic mode but it rapidly segues to England, where the Palladian style was adopted (and adapted) first by Inigo Jones and then a host of well-heeled architectural followers. Pictured: elevation of a palace facade, by Andrea Palladio, early 1540s.

A century later and Palladio's influence becomes harder to detect – the curators have had to resort to a few intellectual contortions to make 19th-century neoclassicism sound even faintly Palladian. Pictured: Town Hall, Borgoricco, Italy, by Aldo Rossi, 1983.

The modern rediscovery of Palladian principles includes Oswald Ungers' convincingly Palladian Glashütte ... Pictured: Glashütte, Eifel, Germany, by Oswald Mathias Ungers, 1988.

... through to Stephen Taylor's tongue-in-cheek cowshed. Pictured: cowshed, Somerset by Stephen Taylor, 2012.

INFORMATION

'Palladian Design: The Good, the Bad and the Unexpected' is on view at RIBA's Architecture Gallery until 9 January 2016

ADDRESS

RIBA

66 Portland Place

London, W1B 1AD

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.