‘Any oyster can make a pearl – only beautiful ones can be jewels’

We delve into the Nagasaki waters with Tasaki’s pearl harvesters in pursuit of a perfectly lustrous cultivated crop

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Lapping green waters fringe the Kujukushima Islands off the coast of Sasebo in Nagasaki. Fields of pearl oysters sleep just beneath their surface. The shell beds are farmed by Tasaki, the Japanese pearl- and diamond- design house that has been harvesting the rare, brown-lipped pearl oyster here since the 1970s. The Akoya, a small white pearl variety with an almost-luminescent lustre, is Tasaki’s speciality.

The pearl farm, where around one million oysters are cultivated every year, is one of three production hubs that form the Tasaki business. The jewellery house also operates a design and production studio in Kobe, and has a flagship, five-storey boutique

in Ginza, Tokyo. This year, Tasaki ventured beyond its native Japan, opening a boutique

on New Bond Street, London, and at The Ritz, Paris.

Tasaki’s annual pearl cultivation process has humble beginnings. In the murky heat between April and November, in a community of rustic, wooden workshops in Nagasaki, a tight-knit team of skilled workers sits at wooden benches, using hypodermic needles to insert nacre nuclei one by one – at a rate of around 800 per day – into live oysters, imported from the Mississippi River. The US variety is prized in Japanese pearl cultivation for its weight, which produces a thicker mother-of-pearl lining. The determining quality of any pearl is lustre; if it’s perfect, you should be able to see your reflection in it.

Left, a studio assistant grades pearls. Right, hand-stringing a Tasaki pearl necklace.

The molluscs are put to sleep while the craftsmen insert fragments of donor mantle and a nacre nuclei. The mantle produces a response to the nuclei, and the oyster is compelled to wrap the ‘irritant’ in layer upon layer of nacre until a smooth, lustrous round is formed. The process draws on the pioneering work of Japan’s Kokichi Mikimoto, who introduced cultured pearls to the world in the late 19th century.

‘Each shell behaves in its own way, like a human,’ the farm’s senior advisor, Masato Yamashita, tells me, as he hoists a basket of oysters fresh from the sea. ‘There are lazy oysters,’ he says, shucking a shell, ‘and there are sensitive ones – and the latter produce more nacre. The thicker the nacre, the shinier the pearl.’

‘Each shell behaves in its own way, like a human. Sensitive oysters produce more nacre. The thicker the nacre, the shinier the pearl.' - Masato Yamashita

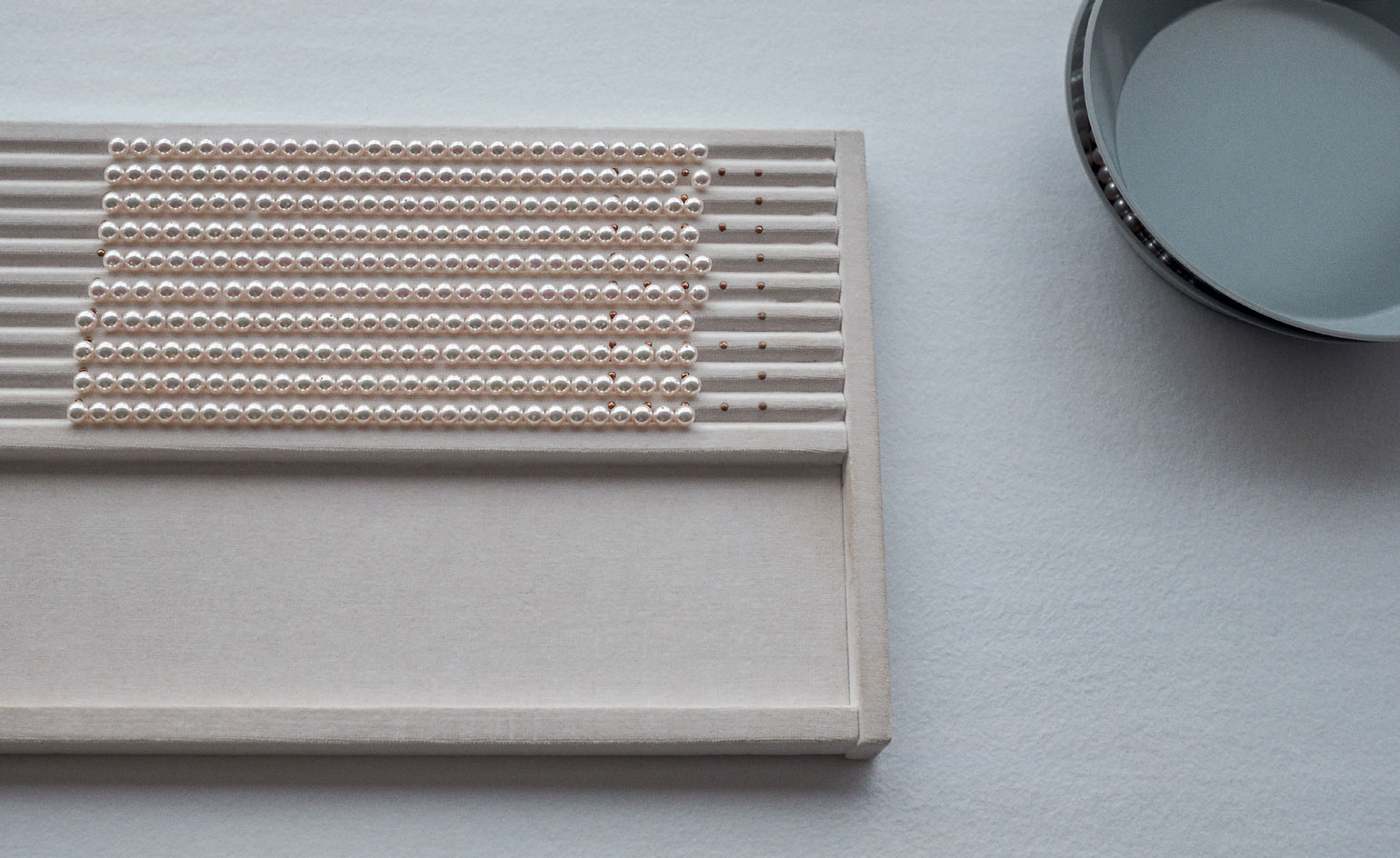

The average size of an Akoya pearl is 7 to 8mm. Pearls are harvested in winter and transported to Kobe to be sorted. The production line is small, with each person taking a bowl of 6,000 pearls per day, which they grade into 30 lots. Sorting studios work from sun up to sun down, experts working by eye and hand in the naturally steady northern light. It takes five years of training to become a sorting expert and up to ten to reach master status.

While one person checks for roundness,

a second is concerned with lustre, a third, blemishes, and the fourth, colour. Graded pearls are shared among the ateliers to be used in classic necklaces

or designer collections by Tasaki’s creative director, the New York-based fashion designer Prabal Gurung. Classic pearl strand production is a key part

of Tasaki’s business, so each day the studio priority is to identify enough pearls of sufficiently high quality to create 20 to 30 necklaces.

Precise holes are bored through each pearl,

so they can be strung. Good knotting techniques

are paramount: each hand-done knot must have exactly the same tension so that the necklace has

a fluid, supple form. This supremely deft method

also incorporates a traditional system that prevents

a pearl necklace from unravelling if the strand breaks.

The Tasaki community has a strong respect for the oysters around which their livelihood revolves. The farm workers are said to feel sad when a pearl

is not forthcoming from a shell they have tended, and hold thank-you ceremonies for the needles

and the oysters. With more than 50 per cent of

every crop destined to die or be phased out because of poor growth, it is the precarious pursuit of the perfect pearl that ultimately defines this historic jewel’s precious nature. As Yamashita tells me:

‘We once tried to control the waters and temperature of the shell beds, but it was not successful.

Nature shapes them. Any oyster can make a pearl – only beautiful ones can be jewels.’

As originally featured in the May 2019 issue of Precious Index

White gold, Akoya pearl and diamond earrings, from the Tasaki London Collection

Tasaki shell beds nestle along the fringes of Japan's Kujukushima islands

Information

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Caragh McKay is a contributing editor at Wallpaper* and was watches & jewellery director at the magazine between 2011 and 2019. Caragh’s current remit is cross-cultural and her recent stories include the curious tale of how Muhammad Ali met his poetic match in Robert Burns and how a Martin Scorsese Martin film revived a forgotten Osage art.