With seismic changes afoot, predicting the next generation of car is about to get much harder

The future of automotive design has never been harder to decipher. Fast-advancing tech and ever-increasing legislative demands on car use are coming up against an emerging generation who seem blasé at best about the advantages of owning, let alone driving, cars. In the past, any such uncertainty would have been brushed aside by futuristic conceptual visions, stoking anticipation and stimulating participation in the glorious tomorrow of personal transport.

From the 1950s onwards, the concept car served a very singular purpose; it demonstrated technology and forms considered too advanced to build or to sell. The far, far future is always a more interesting place to visit, which is why esoteric ideas such as gas turbines and self-driving (General Motors’ 1950s Firebirds), flying cars (every decade or so), outlandishly impractical styling (the work of Luigi Colani) and even nuclear power (the Ford Nucleon, from 1958) lingered in the cultural imagination.

Technology is catching up. Although fission-fuelled four wheelers are definitely out, and the dream of the flying car refuses to die yet never quite takes off, there are other areas where processing power can fulfil long-held predictions. Chief among these are the dreams of a driverless vehicle and, to a lesser extent, the design opportunities afforded by electric propulsion. Put the two together and there are lots of ways to derail how consumers have been taught to think about cars.

Mini's compact vision of the future has a friendly glow with a pared-back, jewel-like interior

In June, the BMW Group block-booked the Roundhouse in Camden, London, an arts and music venue carved out of a former train shed. For over a week, the space was transformed into a mini motorshow at which the firm revealed a striking triptych of future mobility courtesy of the three brands it stewards, BMW, Rolls-Royce and Mini. This year is the Bavarian giant’s centenary. As one of the most switched-on contemporary car-makers, it has shown itself to be adept at brand-building and niche-carving. Now, however, the fight is for the future desires of an as-yet-unconvinced generation of owners.

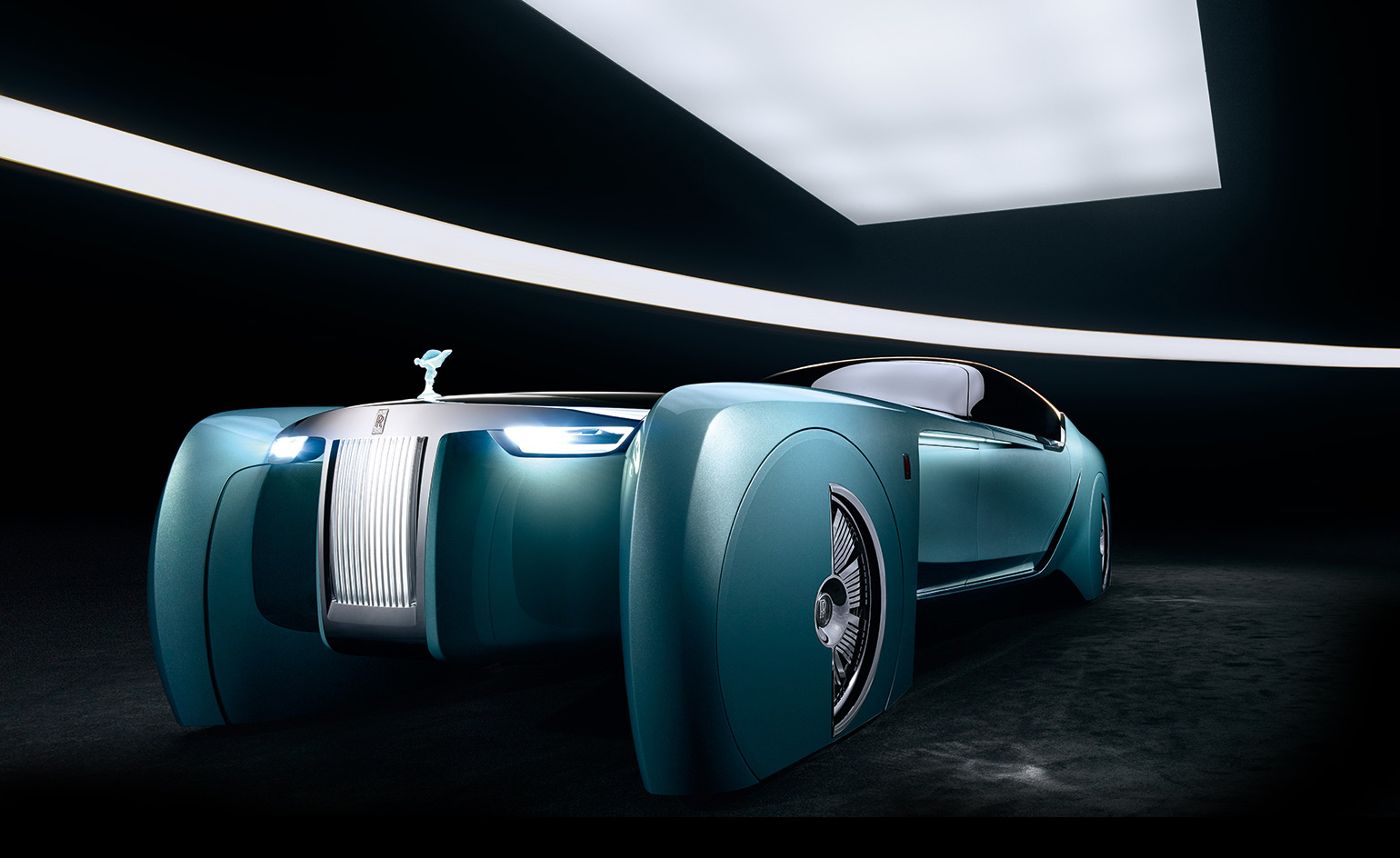

The cars represent the intersection of future technology and brand aspiration. The mighty Rolls-Royce 103EX concept isn’t just about forms and technologies, but a full-tilt trip into the future of one of the world’s most recognisable brands. From the vertical cliff of the marque’s signature grille – here rendered as a screaming maw between two fist-like wheel spats – through to the preposterous sweep of the rear end, the 103EX dominates the environment. It foretells a world where the one per cent have presumably bought their escape from revolution, either through philanthropy or steep taxation, and are safe to roam the world in overt displays of wealth that distract, divert and entertain the masses by their very existence. To a certain extent, a Rolls-Royce already does this, although class-conscious hackles will be raised still higher by the menacing approach of the 103EX’s hand-crafted combine-harvester-like presence.

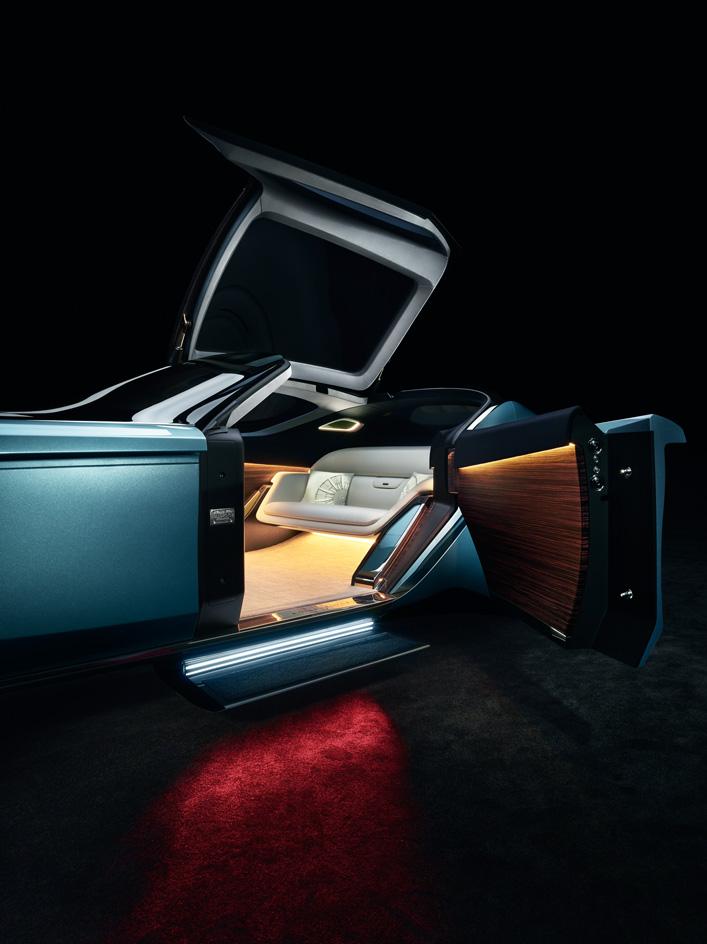

At the heart of the 103EX is an artificial intelligence system coyly named Eleanor, after the model for the original ‘Spirit of Ecstasy’ figurine. Eleanor is a stern-sounding digital concierge, like HAL9000 voiced by Helen Mirren, intended to sort out your life while ensuring you get to the ball on time. She’s the only intrusion into a steering wheel-less interior, a silk-lined ‘grand sanctuary’. The arrival process sees glowing, red ‘carpet’ lighting unfurl from the side of the car and the clam-like canopy open to allow a glamorous, paparazzi-defying step down into the throng. ‘The 103EX is the absolute epitome of future vision,’ says Giles Taylor, its design director (although he prefers the term ‘custodian’). ‘It shows we will never lose sight of what makes Rolls-Royces so special.’

Rolls-Royce’s road-going ‘superyacht’ is one facet of BMW’s brand-centric future. Its flipside is the Mini Vision, a foursquare, pebble-smooth update of the marque’s 60-year-old automotive ideal. Contemporary Minis have been knocking back the protein shakes, with hefty flanks a long way from the original Mini spirit. The Vision strips things back to basics and makes a few fundamental assumptions. This is a car to share. While Rolls’ team imagines their clients ensconced in a world of cybernetic sybaritism, tomorrow’s Mini buyer might not be a buyer at all, just someone who has bought into the idea of it, a purveyor of fun-time transportation. With driver profiles and preferences synched to your smartphone, the Mini Vision adapts instantly to whoever slips in, shifting seats, dash and destination references to align with your desires. Although it’s fully electric, Mini emphasises the ongoing role of driving for fun, implying that this is the sort of shared transport you’ll take if you fancy enjoying yourself along the way. The BMW-badged Vision Next 100 completed the set, a hybrid of styles and technology cloaked in flexible, faceted bodywork. The Next 100 signals BMW’s inevitable evolution away from the ‘ultimate driving machine’ to the ‘ultimate driving experience’.

These three cars are concepts in the purest sense. Sure, they are recognisable as contemporary brands through their proportions, detailing and use of key styling elements, yet the roads, cities and customers they’re designed for don’t exist. Were the concepts of two decades ago any more prescient? Back in 1996, when Wallpaper* first hit the scene, there was no imminent paradigm shift in the auto industry. Electric cars were represented by GM’s EV1 – launched, trialled, abandoned and crushed before the decade was out. No one else even came close. Driverless cars, on the other hand, have been a futurologist’s fetish since the 1950s. By the mid-90s, most driverless research had eschewed the idea of roads embedded with tracks in favour of onboard processing linked to sensors. Industry-sponsored research projects were beginning to explore ways in which driver control could be ceded to machines, and in turn how those early radars and cameras could feed back into safety features.

Mercedes-Benz took a long view with its 1996 F200 Imagination concept. In formal terms, it previewed the 1999 CL Coupe, albeit with a dollop of conceptual gloss in the shape of pivoting doors, but under the skin there was a sure-footed suite of predictions about how future cars would interact with their surroundings. Twenty years on and the F200 looks remarkably accomplished, with its drive-by-wire controls foreshadowing an era – ie, today – when cars are capable of steering, braking and accelerating all by themselves.

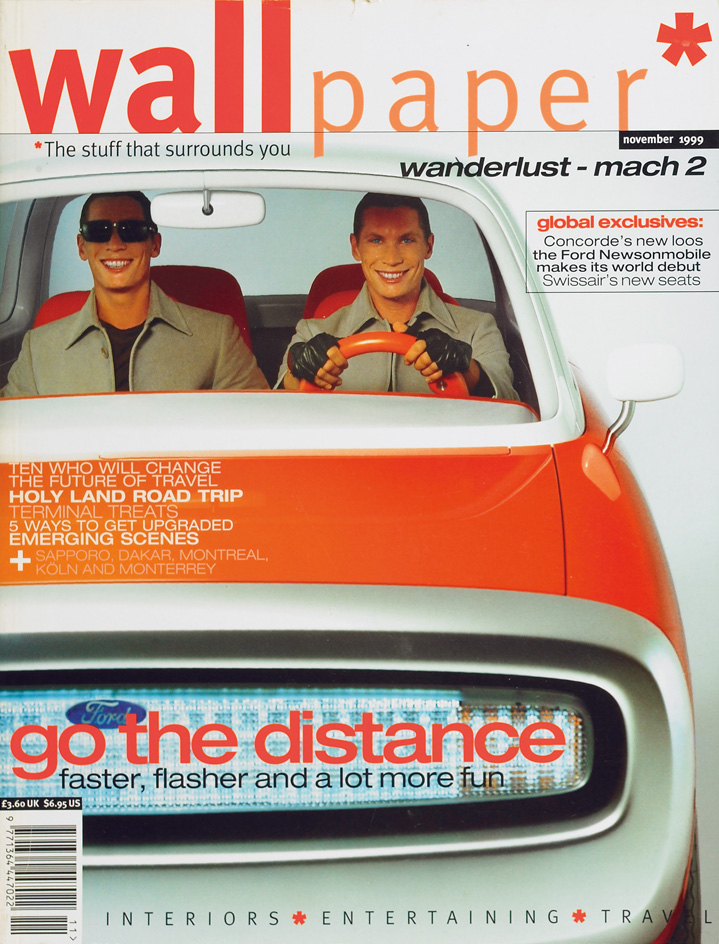

The F200 was more about substance than style; 1996 wasn’t exactly a golden year in car design. The only other notable speculations came from Alfa Romeo – a small, lithe coupé called the Nuvola that singularly failed to lead the company in a much-needed new direction – and Renault, in the form of the Fiftie concept. This retro-esque concoction was one of the industry’s first forays into naked nostalgia, taking the fundamental shape of the famous 4CV, which debuted exactly 50 years before and marked France’s first credible VW rival, setting the scene for the country’s long domination of the small car market. The Fiftie’s bulbous wheel-arches, chunky detailing and compact flair were the Gallic equivalent of VW’s New Beetle, under development in California, and foreshadowed the explicit retro stylings of cars like the Fiat 500 (2007) and Mini (2000). In 1999, Marc Newson showed the 021C for Ford, which was a spirited attempt to steer the global giant towards a new paradigm, before ending up in the cul-de-sac of design history.

Marc Newson’s 021C concept car for Ford made its debut on the cover of W*30 in 1999. The auto equivalent of the iMac G3, it could have driven the big oval in a bold new direction

Future visions rarely benefit from hindsight. They show us how we want the world to be, not how it turns out. True blue-sky projects like the 103EX and Mini Vision are a rare breath of fresh air. Designers relish these opportunities to showcase their skills, creating statements of intent that don’t have to hint at next year’s model. Perhaps it was the absence of an imminent technological revolution that makes the concepts of the recent past seem so straitlaced.

Massive change – in some form – is afoot. Companies such as Tesla have kick-started radical rethinks of the ways cars are designed, built and sold, inspiring a host of identikit rivals from the mainstream manufacturers – and that’s before bold players like NextEV and Faraday Future have entered the game. Google has been trialling self-driving systems for years and Apple is undeniably sniffing around the auto industry (Newson’s hiring in 2014 could be significant). You can be sure that the realms staked out by BMW’s Vision cars are being explored across the industry.

There’s no doubt that autonomous cars are coming, in one form or another. Concepts like these help determine and define if and how brand worship will influence the next generation of cars and owners. Futurology is an unforgiving discipline. When tomorrow comes, the conceptual utopia will simply move further afield (and failed predictions will be quietly forgotten). Yet, whether we like it or not, our cars, roads and ways of using them will all have changed.

As originally featured in the October 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*211)

The 103EX unfurls a carpet of light to allow its passengers to descend in style

Mercedes F200 Imagination, 1996

Styled in Mercede Benz’s Japan studios, the F200 was a tech-filled glimpse into tomorrow’s luxury car

Pininfarina Eta Beta, 1996

The legendary Italian designer eschewed Ferrari-style sleekness with this hybrid city car

Alfa Romeo Nuvola, 1996

Walter de Silva, later head honcho at VW Design, oversaw this neat sports coupe concept, a missed opportunity

Renault Fiftie, 1996

Penned by future BMW i designer Jacob, the Fiftie was a robust take on retro-futurism

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.