From mighty modeller to master builder: Thomas Heatherwick on the glory of making

Some of the largest architecture projects in the world are taking shape in a ground-floor atelier tucked away in London’s King’s Cross. Thomas Heatherwick set up his studio in 1994 after studying at Manchester Polytechnic and the RCA, and over the years he gradually scaled up its output, creating everything from furniture and installations through to buses, bridges, art museums and whole city blocks. Heatherwick now works alongside around 200 designers, 130 of whom have architectural training. The studio output is focused on big buildings. These include one of the largest mixed-use projects in China, a key component of a vast US private development, a California office for a tech colossus, and a new bridge for London, all of which are at various stages of planning and construction.

Despite this mega-structural ambition, every Heatherwick project can be infinitely zoomed into, right down to the smallest design component. This combination of scale and detail comes out of an absolute commitment to process, something that becomes evident the minute you sit down with Heatherwick to talk about his work.

A mock-up of this issue’s cover, handmade with brass fasteners and cut card to illustrate the concertina-like mechanism within, is a textbook example of Heatherwick’s approach: a low-tech but delightful piece of paper engineering to create a simple but effective transformation. One of the inspirations behind the piece was a prototype circular table, fabricated from compressed and glued paper. Concealed within the ribs is a mechanism that allows the table to be expanded into a long oval in one smooth movement.

Like so many of the studio’s projects, it represents the intersection of engineering, design and making. Heatherwick used to believe he was originally misrepresented as a sculptor, frustrating when he always wanted to move towards architecture. ‘I didn’t see any separation – it was clear to me from very early on that everything was designed. My first thesis at Manchester, 25 years ago, looked at the role of making in the design of buildings,’ he says. ‘I had a hunch that it was something that was not finding its place.’ His very first structure, a pavilion to which he dedicated his final year at Manchester, was completed in collaboration with Aran Chadwick (now of Atelier One structural engineers). ‘I thought I’d risk the first two years of my degree to gamble my third year on making an actual building – I knew that you didn’t learn by just making a card model.’

In addition to the many models and mock-ups of their own work, the King’s Cross studio space is a treasure trove of objects, mostly bold and sculptural, often taken far out of context and detached from their original purpose. This is industrial design’s guilty little secret – that unintended abstraction tends to aestheticise objects in ways their makers couldn’t possibly have conceived. ‘My initial response was that the balance between thinking and doing was disconnected,’ he says of his student years. ‘Why couldn’t the physical environment meet that expectation?’ What sets Heatherwick apart is his innate understanding of how to reinvigorate this separation.

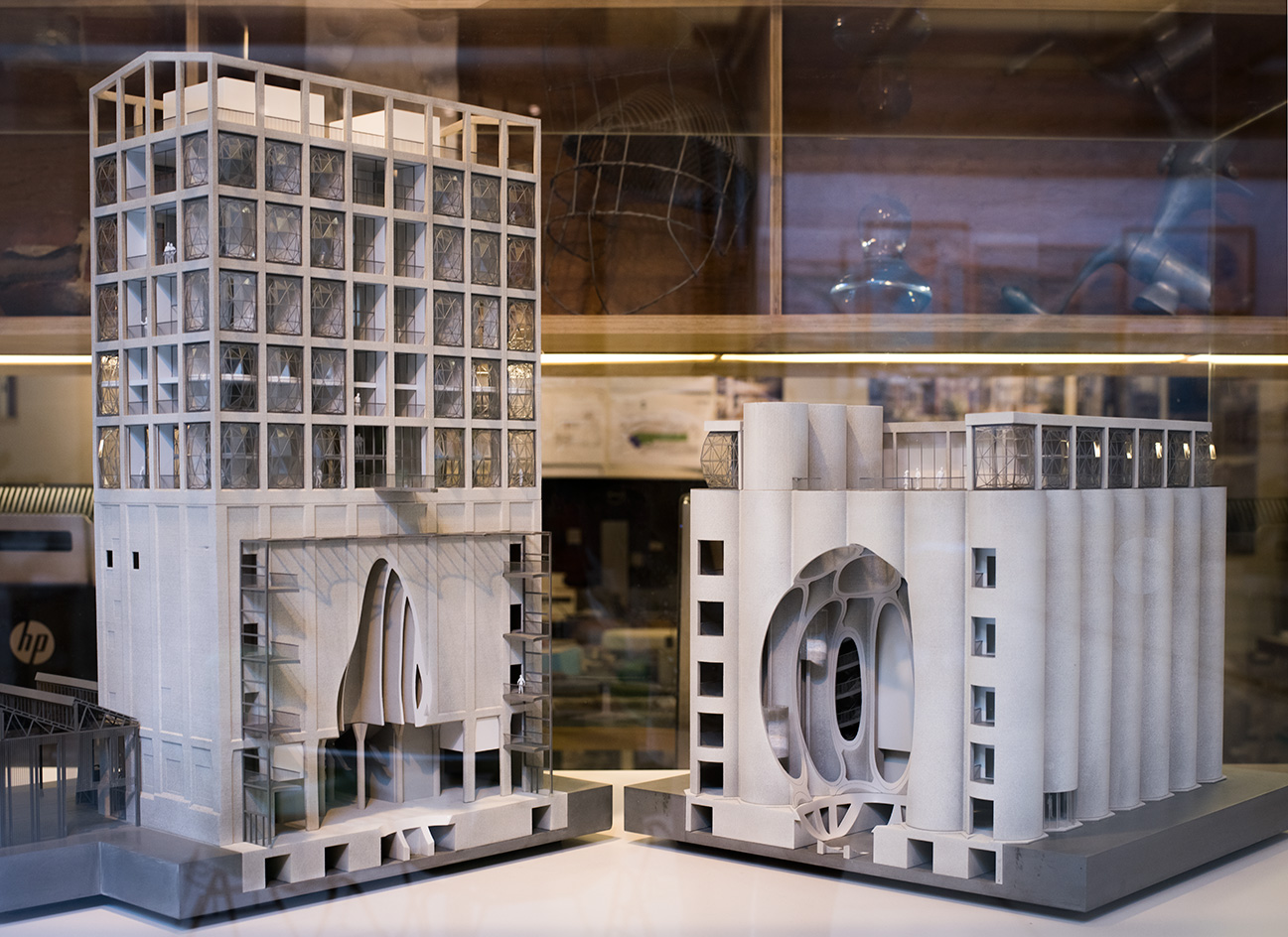

In Cape Town, work continues on the conversion of a towering waterside grain silo into the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa. The 57m-high structure on the city’s Victoria & Albert Waterfront is set to become a new urban destination, with a hotel above and 6,000 sq m of galleries below. Founded by former Puma CEO Jochen Zeitz to house the collection of contemporary African art he began in 2002, MOCAA is due to open in spring 2017. The original building is dramatic enough, but rather than advocate full-on, Bilbao-style intensity, Heatherwick took the curator’s suggestion of creating interior drama – all the better to draw people inside and hence be more likely to view the collection. Heatherwick has spent many hours on-site, helping oversee what will become the collection’s signature space – a vast internal atrium carved from the concrete silos (‘We could either fight a building made of concrete tubes or enjoy its tubeyness,’ he wrote). The abstract, organic form is cut out from what is already there. ‘The quality we’re looking for is that it must look and feel like a hot wire has run through it,’ Heatherwick explains, although the reality is considerably harder and dustier as the decades-old concrete is hammered, smashed, grinded and polished into shape. ‘I have been training the guys [on site] to feel by hand when it was right,’ says Heatherwick, always able to boil the most heavyweight industrial process down to skill and feel.

‘Our projects are an interplay between the ordinary and the exciting,’ says Heatherwick, mindful of the importance of background elements, whether it’s method or materials, space or form, deliberately allowed to lie fallow while our magpie minds fixate on the shiny and new. Partly this is down to the rapid change and evolution of visual culture, in an era when even the most sophisticated architectural project can be compressed into a single visual soundbite for dissemination, posting, liking and sharing. It’s a temptation Heatherwick cleverly accommodates. At Bombay Sapphire’s new distillery in Hampshire, he points out that the studio dealt with ‘49 historic buildings, as well as widening a river. We actually only built two things. And they fit in the photograph.’ This afterthought is telling, as much of the studio’s success is down to an understanding of the importance of these photogenic moments.

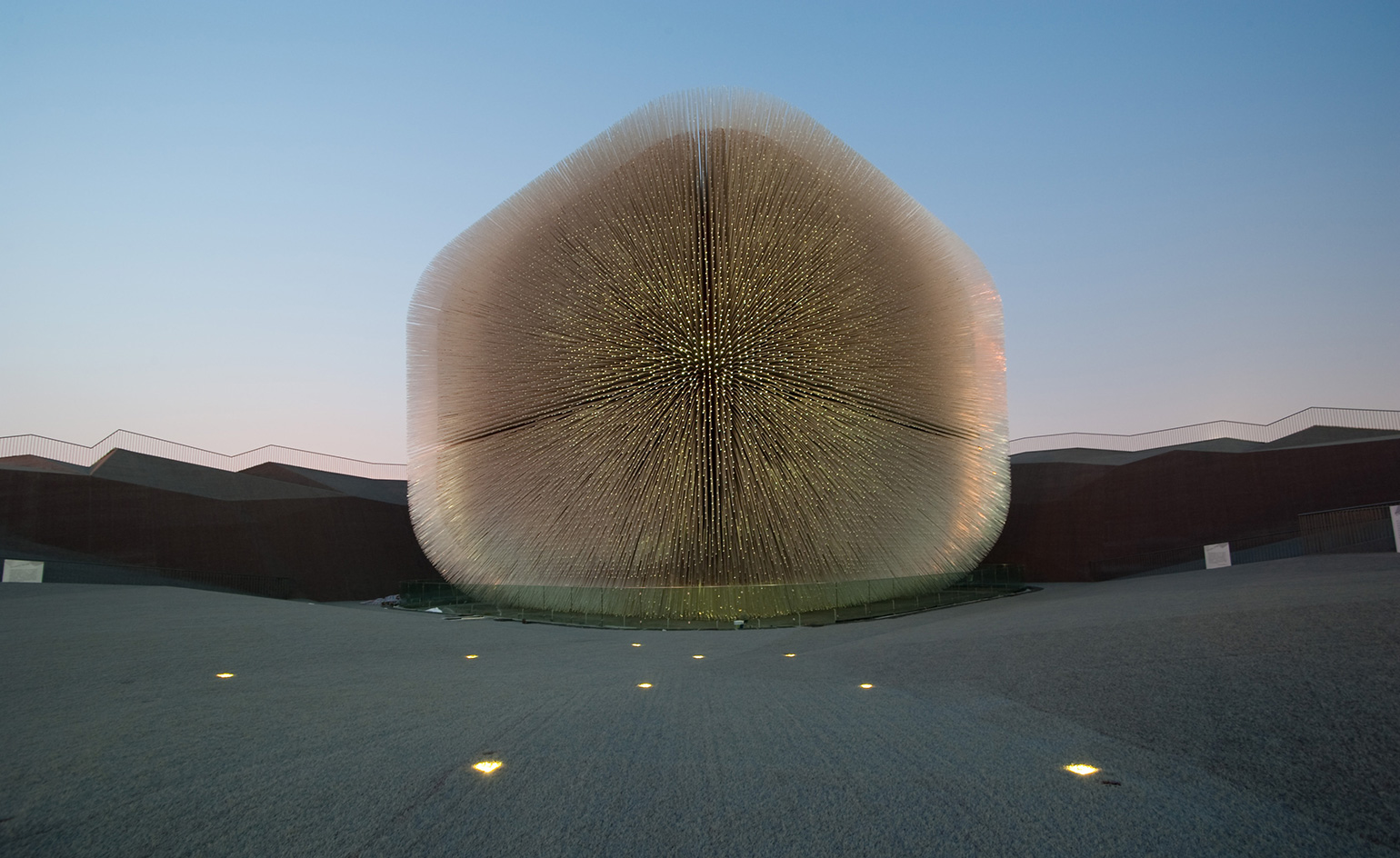

Heatherwick also cites the UK Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai Expo, a scaled-up version of his original ‘Sitooterie’ from 1999, only with each strand of ‘hair’ created from a 7.5m piece of optical fibre, with a unique seed embedded at its tip. The 20m-high 'Seed Cathedral' was one of the stars of the entire exhibition, yet as Heatherwick recalls, it had barely half the budget of its rivals, even though the brief explicitly called for it to receive the top five visitor numbers out of some 250 pavilions on the vast site. ‘That drove the strategy,’ he says, ‘so we designed five-sixths of the site to be ordinary.’ Although the pavilion itself is what everyone remembers, it was set on a plinth that the designer says was intended to be ‘deliberately unmemorable’.

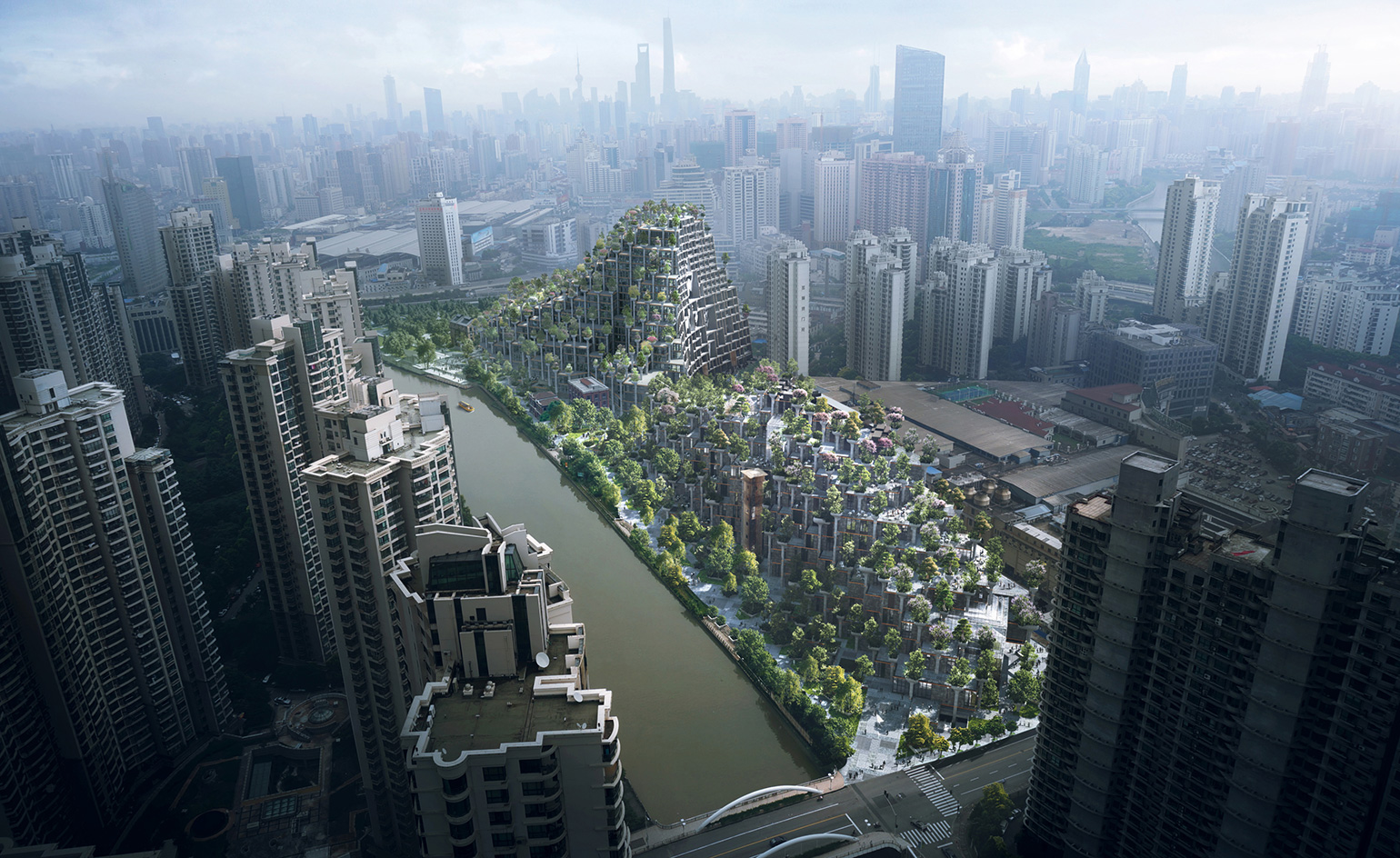

Many of the studio’s architectural projects get their expressive, expansive qualities from clever replication and duplication of carefully designed elements. The Learning Hub building at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University is a case in point. ‘It cost less than a multi-storey car park,’ the designer says, explaining how a universal mould was used to shape various poured concrete components. Along Shanghai’s Moganshan Road, the city’s long-established art district, another mega structure is emerging. Occupying a 15-acre site, the new mixed-use development is described by the studio as a ‘piece of topography’, an urban mountain range in the middle of Shanghai’s cityscape. The greenery consists of 1,000 mature trees, including indigenous Chinese pines, set among tree-like poured concrete columns, which in turn form 200 outdoor terraces. ‘Nothing is small in China,’ Heatherwick comments.

Big projects can spark controversy, though. London’s Garden Bridge, although signed off, approved and partly fabricated, still seems to be hanging by a thread. ‘Our job is to hold up the garden and get out of the way,’ Heatherwick says. ‘It was not about making a massive thing, although it has to work from many dimensions.’ For the most part, the designer steers an apolitical and pragmatic path, but issues like the evolution of urban space into collaborations between the public and private sector, and the dominance of the latter, inevitably surface. At times, he seems almost pained by the negativity. ‘We all want to do something special and wonderful – we’re just trying to harness people’s passions,’ he says. ‘Humans underestimate humans all the time. We extrapolate problems to an enormous extent, but when pushed, humans are also brilliant problem solvers.’

At the same time, he notes that ‘it’s depressing when something hasn’t got the confidence to be ordinary’. He adds, ‘The role of designer has become disproportionately exalted. It’s unfortunate – the glory of making has been lost.’ Pragmatism and optimism rarely come together as credibly as this. ‘The projects I enjoy most are the ones that are unexpected, and the public realm is the best place to find those unexpected qualities,’ says Heatherwick. ‘It’s frustrating when people think our projects are expensive.’

As you fold, squash and stretch your Wallpaper* Friction Cover, consider that you’re holding one of the smallest and most intricate projects to come out of the Heatherwick Studio for many years, a true return to the surprise and delight conjured up by the earliest works. Scaling up this level of focus is hard work. ‘You need endurance and perseverance for these big projects. The world underestimates how hard it is to design and build buildings,’ he says. Nonetheless, the major works keep on coming, including a new retail space in the revitalised goods yards of King’s Cross and a new football stand at Fulham FC. ‘In 20 years, we’ve gone from two to 200 people,’ Heatherwick says. ‘I picked up my student manifesto the other day, and what we do now is a spooky manifestation of what I’d written. Right now I feel like we’ve only just got going.’

Thomas Heatherwick is one of our 20 Game-Changers. Read about the other 19 here

As featured in the October 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*211)

A model showing the complex interior of the South African Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town

The Learning Hub at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore

Heatherwick’s 'Seed Cathedral' – the UK Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai Expo

His 15-acre mixed-use development, under construction on Shanghai’s Moganshan Road

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Heatherwick Studio website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.