Buena Vista Culture Club: following Chanel’s foray, W* explores a Cuban creative revolution

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Number 8 Calle Este, between 37th and Parque, in Havana, is a significant address in the history of the Cuban revolution. The whitewashed house used to belong to René Vallejo. His books still line the shelves. One is called Communist Guerrilla Warfare. Another is uncannily prophetic. It is named Ironies of History.

Vallejo was a doctor who fought alongside Fidel Castro in his rebel army and became the Cuban leader’s personal physician after the Communists overthrew dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959. When the spoils of the revolution were divided up, Vallejo got one of the biggest houses in one of the most fashionable neighbourhoods of the capital, Nuevo Vedado.

Today, the four-storey structure plays a new, very different political role. After Vallejo died and his family upped sticks to – don’t tell Fidel – the US, the property was bought by Los Carpinteros (The Carpenters). They are Cuba’s most acclaimed artistic collective, founded in 1991 by Marco Antonio Castillo Valdés, Dagoberto Rodríguez Sánchez and Alexandre Arrechea, who has since left.

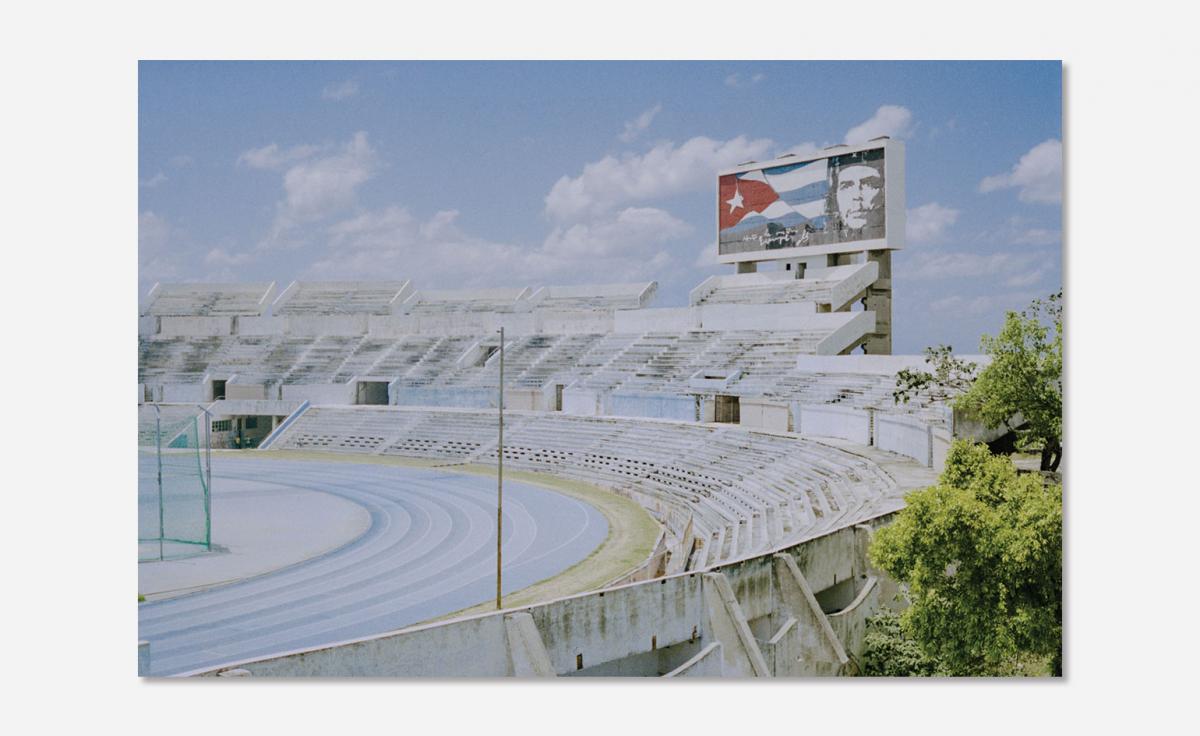

Their latest work, on display in the studio, is a series of billboards that satirise the political advertising Fidel’s Communist Party still uses to exhort Cubans to stay true to his revolutionary ideals. Instead of the usual messages – ‘Socialism or Death!’ Or ‘Commander, we are ready!’ – the slogans read: ‘Fidel has cocked it up’ and ‘The whole place is ruined’.

It’s a witty – and shockingly refreshing – comment on decades of Communist mismanagement that has left Cuba a banana republic that is so broke it cannot even grow bananas for its people. Ananda Morera, who runs the studio, explains: ‘People do

not believe a lot of government advertising. Los Carpinteros use the real phrases of people in the street and make them into billboards.’

As well as capturing the Cuban creatives behind the country's new cultural revolution, New York photographer Daniel Shea shared his personal travel diary with Wallpaper*. See it in full here...

Much has been written about Cuba’s new economic revolution, kick-started by US president Barack Obama and Raúl Castro, Fidel’s younger brother and successor as Cuban leader. Between them, they have ended 57 years of hostility between their two countries, introduced free market reforms, and loosened the US economic embargo. Hundreds of thousands of Cubans have set up private businesses and Western firms, notably Iberia, Virgin Atlantic, Starwood Hotels, Nestlé and Unilever, are investing.

Rather less has been written about the cultural revolution that has been sparked by free(er) speech and greater tolerance

of artistic independence – developments that have accompanied the economic liberalisation. The world has long known about Cuban ballet and music, mainly in the lithe form of Carlos Acosta and the mournful tunes of the Buena Vista Social Club. Cuban artists have begun to make it into the occasional international show, notably Art Basel in Miami, where local Cuban-American collectors champion their work. But, for most observers, that has been about it. Stand by to make up for 57 sluggish years. Cubans are back in the culture business in the broadest sense, from art to media, through design and hospitality.

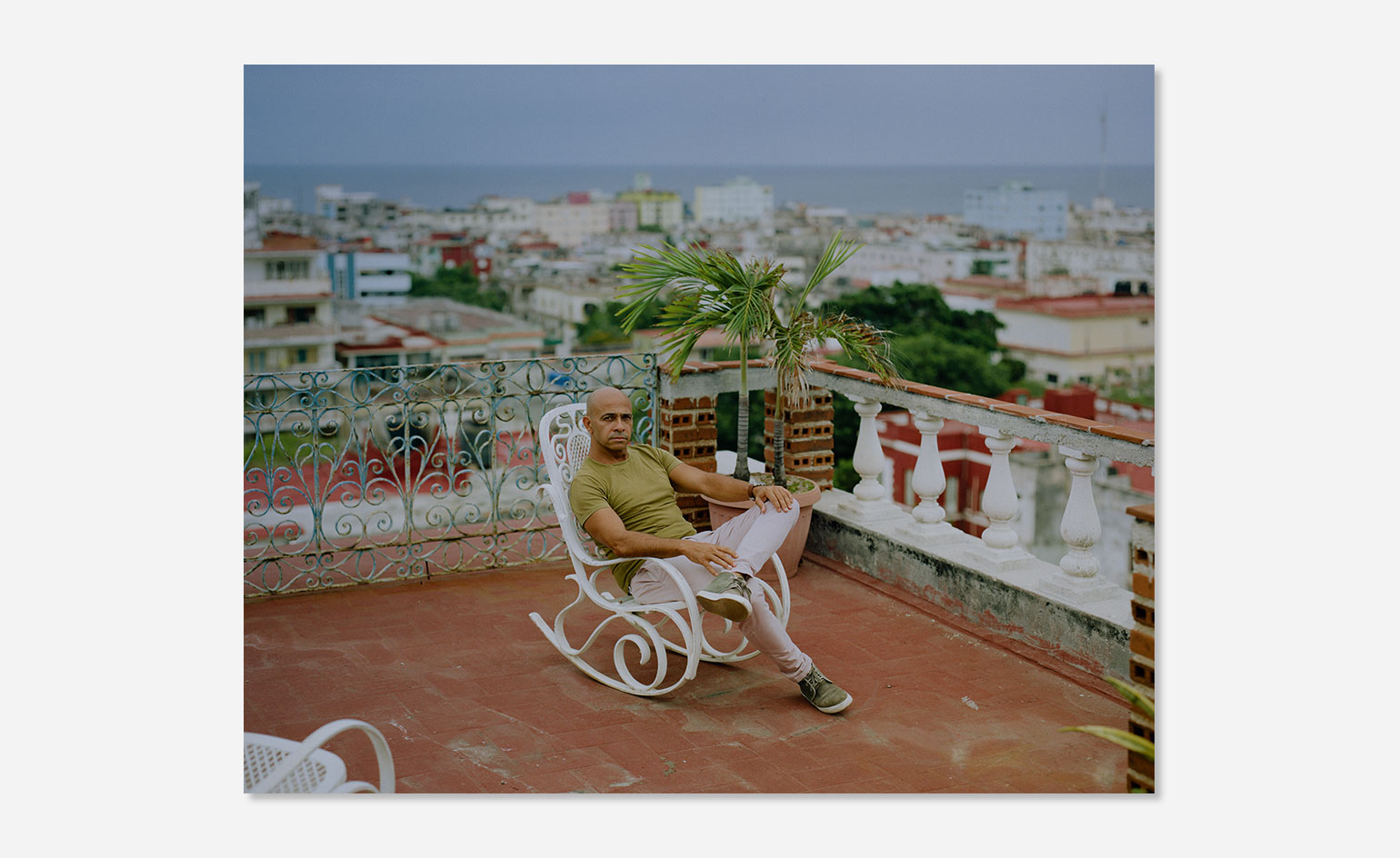

‘There’s an explosion of talent,’ says Ydalgo Martínez, as he greets me when I step out of the rickety lift that sways unnervingly up to his penthouse, which looks out over the Malecón, Havana’s corniche. Martínez has returned to Cuba to set up a design and property development firm, after working for Swiss fashion house Bally in Zurich. Cubans can now buy and sell homes freely and plucky overseas investors, who are still banned from owning bricks and mortar, are partnering with locals to purchase real estate.

Martínez buys up property and searches old homes, flea markets and antiques shops to do them up. He likes to mix styles that reflect Cuba’s history – colonial, midcentury modern, contemporary – to create a uniquely Cuban aesthetic. ‘The whole point of being in Cuba is to be Cuban. If you make a house, it’s important to make it with a sense of Cuba. We are in Havana, not London!’

Finding antiques is easy, he says. ‘People have amazing furniture from the 1940s and 1950s in their homes. I buy it, renovate it and put it in my houses.’ Murano glassware is easy to come by, too, thanks to the large number of Italians who lived in Havana before the revolution. If he needs anything modern, he imports it from Panama, where prices are low.

Raúl’s economic reforms have sparked a boom in artisanal companies, which helps Martínez. ‘For the first time, I can find private carpenters, upholsterers and fabric restorers. Cuban people make great furniture. Cuban skills and cash from overseas – they are a good team,’ he grins.

Glenda León is another Habanero who is back living and working freely for the first time in her home town. Noted for her experimentation with sound and music, issues of femininity and video art, she is one of a new generation of artists that is, at last, replacing the old iconography of Cuba – 1950s American cars and faded grandeur – with something fresh, modern and outward looking. She grew up in the politically stifled 1980s and Orwellian ‘Special Period’ that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, when Moscow’s financial support of its Caribbean satellite ended and the economy collapsed. It was a fallow, callow time for the arts. ‘In the 1980s, all the artists felt the need to express the problems of censorship. Some went to jail. Others left the country,’ she says. Including herself. She took up residencies in Paris, Cologne, Madrid and Montreal. But now she has opened a new studio in Vedado in a 1940s house that will be her permanent artistic home.

Like Los Carpinteros, she is taking advantage of the growing freedom of expression. In one of her most celebrated works, Summer Dream (Horizon is an Illusion), 2012, she persuaded the city authorities to fill the vast swimming pool at the base of the iconic FOSCA building, which had been dry for decades. Then she turned it into her take on the literal and figurative gulf between Havana and Miami. She created a huge street map of each city at either end of the pool and encouraged locals to swim its length, from one to the other – a controversial invitation in a country where so many still try to escape by sailing to Florida. Thousands took

a dip, much to their and her delight. ‘The neighbours were so happy when they saw it, they wanted to make a cake for me,’ she grins.

Like Martínez, León is enjoying working with local artisans. Since she uses found materials, including audio tape and chewing gum, her pieces need to be box-framed, with a separation between the glass and the backboard. As recently as five years ago ‘no state carpenter or framing house would or could do it. Now I’ve found a couple of entrepreneur carpenters who do it better than anyone,’ she says.

In spite of the new freedoms local artists now enjoy, León is delighted that some Cuban idiosyncrasies remain in the arts scene. ‘Havana’s Biennial is now a Triennial because of budget restrictions, but it is still called the Biennial,’ she laughs.

It’s not just economic and social liberalisation that has sparked the culture boom. One of the most famously unchanged societies, set economically and culturally adrift before most of its population was born, has finally entered the internet age. Raúl has ditched rules that restricted the web to the offices and homes of senior officials of the Communist Party, trusted academics, artists, sports stars, approved journalists, doctors and hotels reserved for Westerners. The communications revolution has triggered

an explosion in publishing and media.

Marita Pérez is the 26-year-old editor of On Cuba, a new Havana-based online magazine that is pushing the boundaries of free speech. Hot-desking in an office in a peeling tower block on the seafront, she tells me: ‘We are very polemical and we attract a lot of readers. We are pioneers. I can speak about everything now. I am young. I have nothing to lose. It’s a good time to be in Cuba and to practise journalism.’ That is the most remarkable – and uplifting – thing any Cuban has said to me since I first visited in 1993.

On her ageing desktop, Pérez shows me how respondents on sites like On Cuba and others are beginning to discuss the future of their country with unprecedented frankness. One columnist on a site called El Estornudo, Juan Orlando Pérez, describes Cuba as a ‘failed state… a prison whose people have no opportunities’. It could not be more different from the turgid state TV and the local rag, Granma, which is the dullest and most stiflingly politically correct newspaper outside North Korea. However, Pérez cautions that speech is still not wholly free. The internet remains censored.

Those who do not have access to the web can still get their fix of independent news and culture, thanks to something called the ‘Weekly Package’. These are memory sticks distributed among Cubans on the black market. They contain films, TV shows, video games, glossy magazines and books from inside and outside the country.

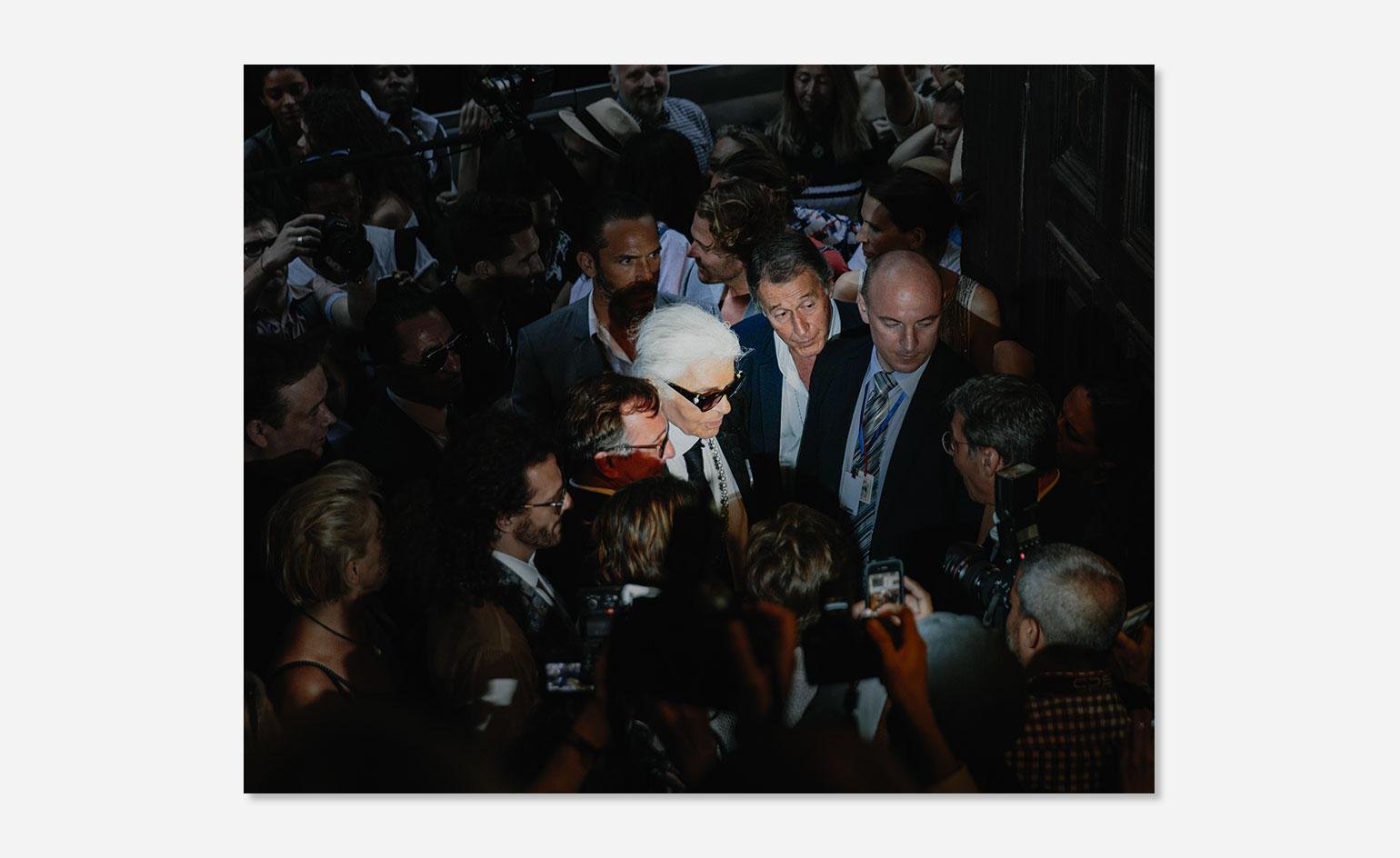

Westerners, notably Karl Lagerfeld, Chanel’s creative director, have moved quickly to take advantage of the new web access. He posted behind-the-scenes images from May’s Cruise collection show direct to the world. Lagerfeld flew more than 700 people to Havana to watch the spectacle on a specially constructed catwalk on the Paseo del Prado. It was French Culture month in Havana and the famous promenade was rich in cross-cultural symbolism. The boulevard was designed in 1928 by French landscape architect Jean-Claude Nicolas and showcases eight bronze lion statues created jointly by his compatriot sculptor Jean Puiforcat and Cuban artist Juan Comas.

The fact that Chanel’s $1m show – planned by a Chanel team that had been based in Cuba for months – took place the same week that the first American cruise ship for four decades docked in Havana looked like a masterstroke of cultural synergy, although Chanel resisted the temptation to make any capital from the timing. ‘There is no political message, no aim other than being here and being able to present a collection inspired by this Cuban culture in Havana,’ Bruno Pavlovsky, the French label’s president of fashion, told Wallpaper*.

The local cool kids might not be able to afford Cruise-wear outfits worth $20,000 just yet – that’s 50 years’ wages for most Cubans – but they have enough pesos to pay the cover charge to get into the Fábrica del Arte Cubano (FAC), a fashionable new club-cum-gallery in Havana. Local musician and artist X Alfonso created it by converting a state-owned warehouse in Vedado into multiple gallery and performance spaces. Columnists in state-run newspapers have criticised him and the crowd of mobile phone-waving hipsters he attracts as ‘too capitalistic’. But Alfonso knows how to navigate the delicate local cultural politics. He has classified FAC as a ‘community project’, enabling him to occupy government property while pushing the boundaries of creative expression.

The two sectors that have grown the fastest in Cuba in recent years are hotels and restaurants – because that’s where the tourist dollars are. On one of those Cuban mornings that is so hot you swear your brain is a conch fritter, I meet Daymarys Camejo. She is converting her 1946 house near the beach in the Miramar district of Havana into the city’s first boutique hotel. She is working with her Italian business partner, Elisa Avalle, who used to be a Dolce & Gabbana model. ‘We both used to work in fashion in Milan and one day I said to Elisa: “Now is the time to invest in Cuba.” She trusted me to create a boutique hotel, which is our dream.’

When it opens this Christmas, Milano will have just six rooms, gardens with water mirrors and fire pits, a café and a boutique selling Cuban-designed and made clothes and accessories. The interior will blend the original aesthetic – the house was designed

by modernist pioneer Max Borges – with minimalist chic. The target market is the growing class of Cuban YUMMIES (young upwardly mobile Marxists), and wealthy Westerners. ‘There is a new clientele in Cuba. Chanel’s visit shows that,’ Camejo says.

Down the road, in a converted factory, Roberto Fernandez is trying to do for food what Camejo is doing for hotels. He’s the kind of man who could only exist in Cuba. He was born in Ukraine, but, growing up, spent summers in Cuba. His father was a Cuban diplomat. After training as a chef in the US, he moved to Havana in 2011 to open a Russian restaurant called Nazdarovie, decorated with Soviet flags. It became wildly popular, especially with American visitors, who saw it as a way of tasting two exotic, once-forbidden fruits for the price of one – the old Soviet Union and Cuba.

Then he came across an old cooking-oil factory, which reminded him of New York. It was renovated and reopened, as El Cocinero, with a rooftop tapas bar and a fine dining restaurant downstairs on a terrace built around an avocado tree. Fernandez’s new menu encapsulates his uniquely modern interpretation of Cuban food. Think grouper fillet with papaya and coconut curry.

Cubans’ love of cooking, and restaurants themselves, almost died under the double cosh of communism and the US embargo that made daily life a struggle for decades. ‘There’s been little but rice and beans and omelettes here for years, so it’s no surprise that there’s still a lack of professionals,’ Fernandez says. ‘We need a culinary school of international standard. But we’re getting there.’

It’s a feeling shared by artist Adonis Ferro, whom I meet in his studio in Old Havana. He is in talks with curators at MoMA and Tate Modern about doing shows in New York and London. Although ‘art and artists are more visible now’, they are not taken seriously enough internationally, he frowns. ‘Western galleries see Cuban artists as emerging artists, even though many of them are already very well known here. They don’t think we make a difference in the art world. In the future, we will prove them wrong.’

The way things are going, it won’t take too long.

As originally featured in the September 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*210)

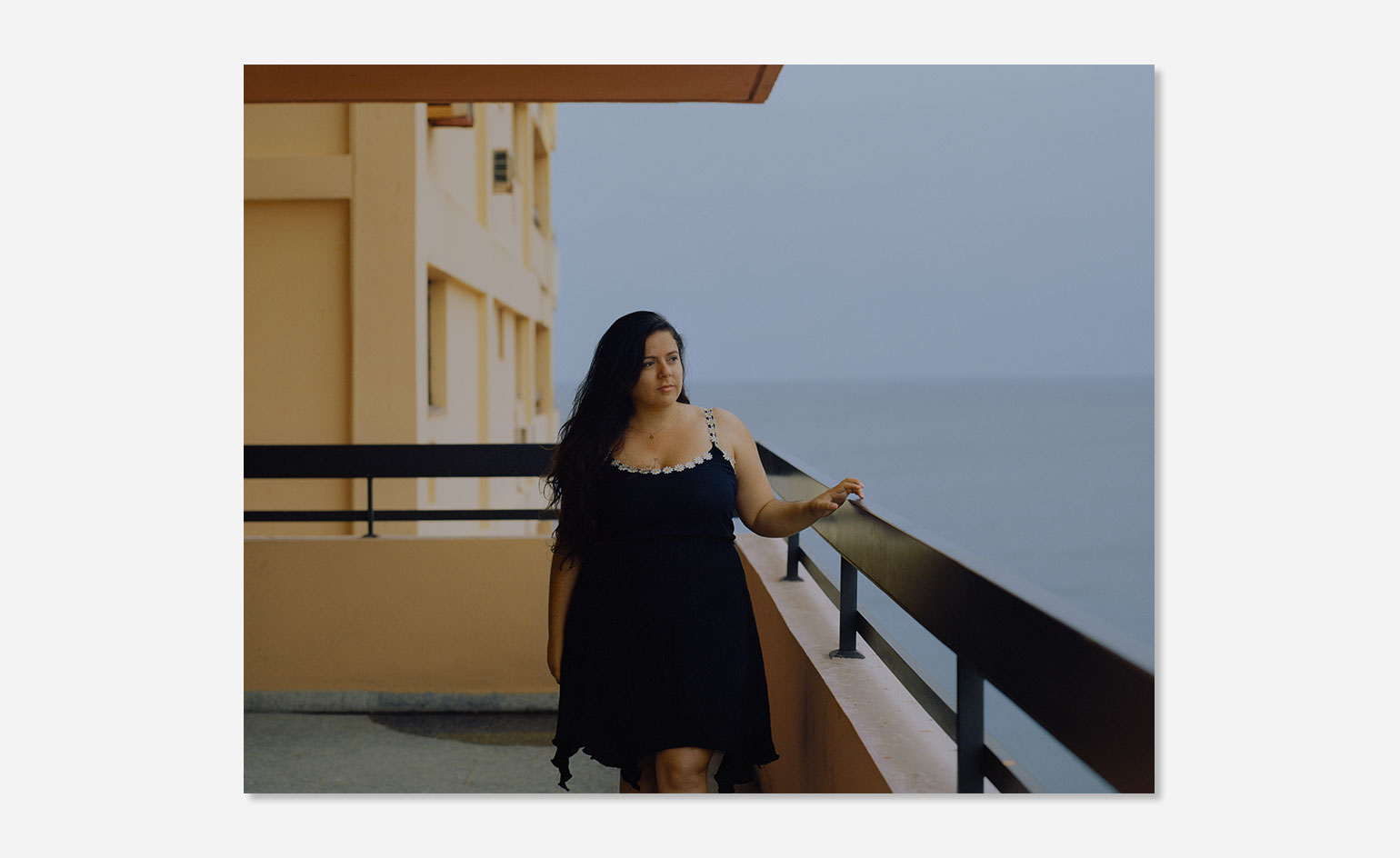

Daymarys Carmejo, hotelier: Carmejo quit her job in fashion in Milan to return to open Havana’s first boutique hotel

Marita Pérez, journalist: Pérez, the editor of online magazine On Cuba, at her seafront office in Havana, where she is pushing the boundaries of free speech

Roberto Fernandez, chef: US-trained Fernandez at his new restaurant, El Cocinero, a converted cooking-oil factory, where he is reinventing modern Cuban cuisine

Ydalgo Martínez, property developer: Martínez, pictured at his penthouse in Vedado, creates homes with the growing number of local artisanal companies

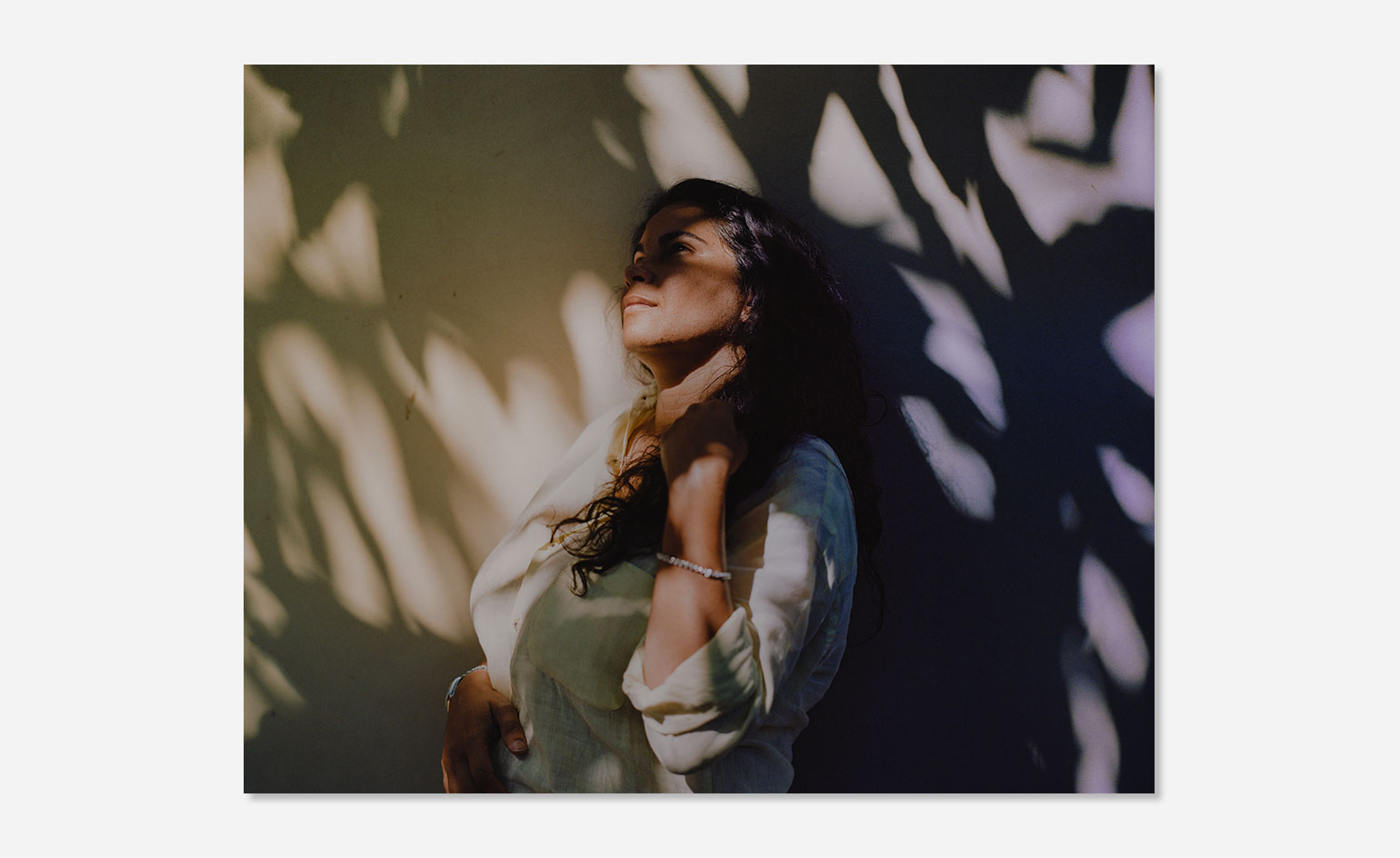

Glenda Léon, artist: Léon, with Habitat (2004), has returned from residencies overseas to open a new studio in Havana

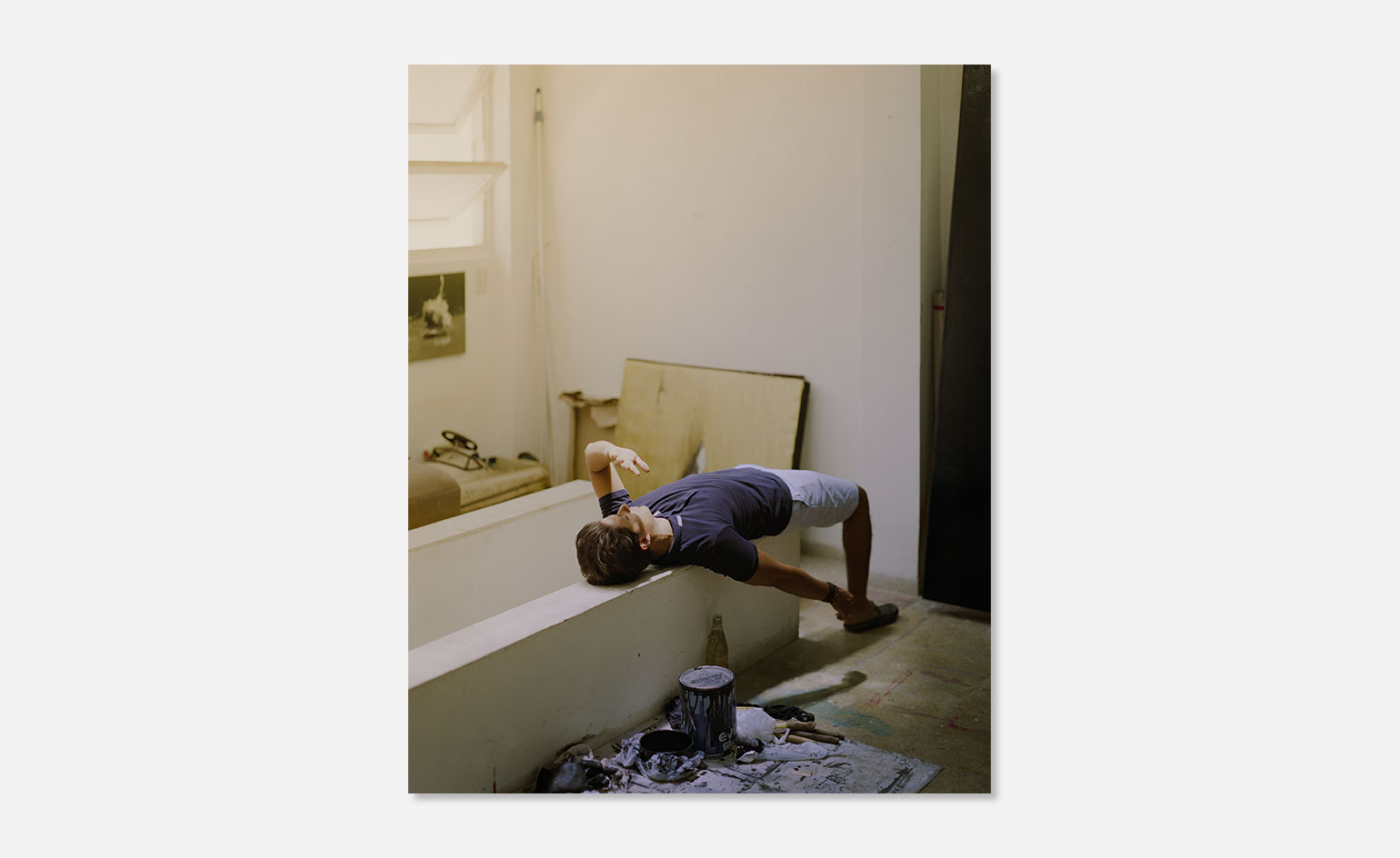

Adonis Ferro, artist: Ferro, photographed in his studio in Old Havana, is in talks to display his work at New York’s MoMA and London’s Tate Modern

Karl Lagerfeld talks to Cuban journalists at the first major Western fashion show in Havana in a generation, in May

INFORMATION

Photography: Daniel Shea

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.