Remembering Ken Garland (1929-2021)

Ken Garland – the designer, educator, writer and activist – has died at the age of 92

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

One of the most pre-eminent British post-war designers, Ken Garland had a long and distinguished career as a commercial designer but was also passionate about ethics, particularly the use and abuse of imagery for advertising purposes. Born in 1929, he was fascinated by graphic and commercial art and collage from a young age. At the age of 16, Garland went to study ‘commercial design’ at the West of England Academy of Art in Bristol, now part of the University of Western England. He graduated in 1947, undertook his military service and eventually found himself at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London. It was a fertile time for British design education. His tutors at Central included Anthony Froshaug and Herbert Spencer and among his fellow students were the Pentagram founders Alan Fletcher and Colin Forbes, together with designers Derek Birdsall and DRU member Alan Ball.

Garland’s first major role was as art director at Design, the magazine founded by the Council of Industrial Design, forerunner of today’s Design Council. It was an ascetic, high minded journal, forever at odds with the burgeoning consumer economy that was re-shaping the British economy around it. As a result, Design tended to be rather disparaging about the excesses – visual, hyperbolic and stylistic – of the more commercially-focused approach taken by the Americans, where the roaring economy was driven by a strong emphasis on graphic art and bold forms.

Council of Industrial Design, 171, March 1963, designed by Ken Garland

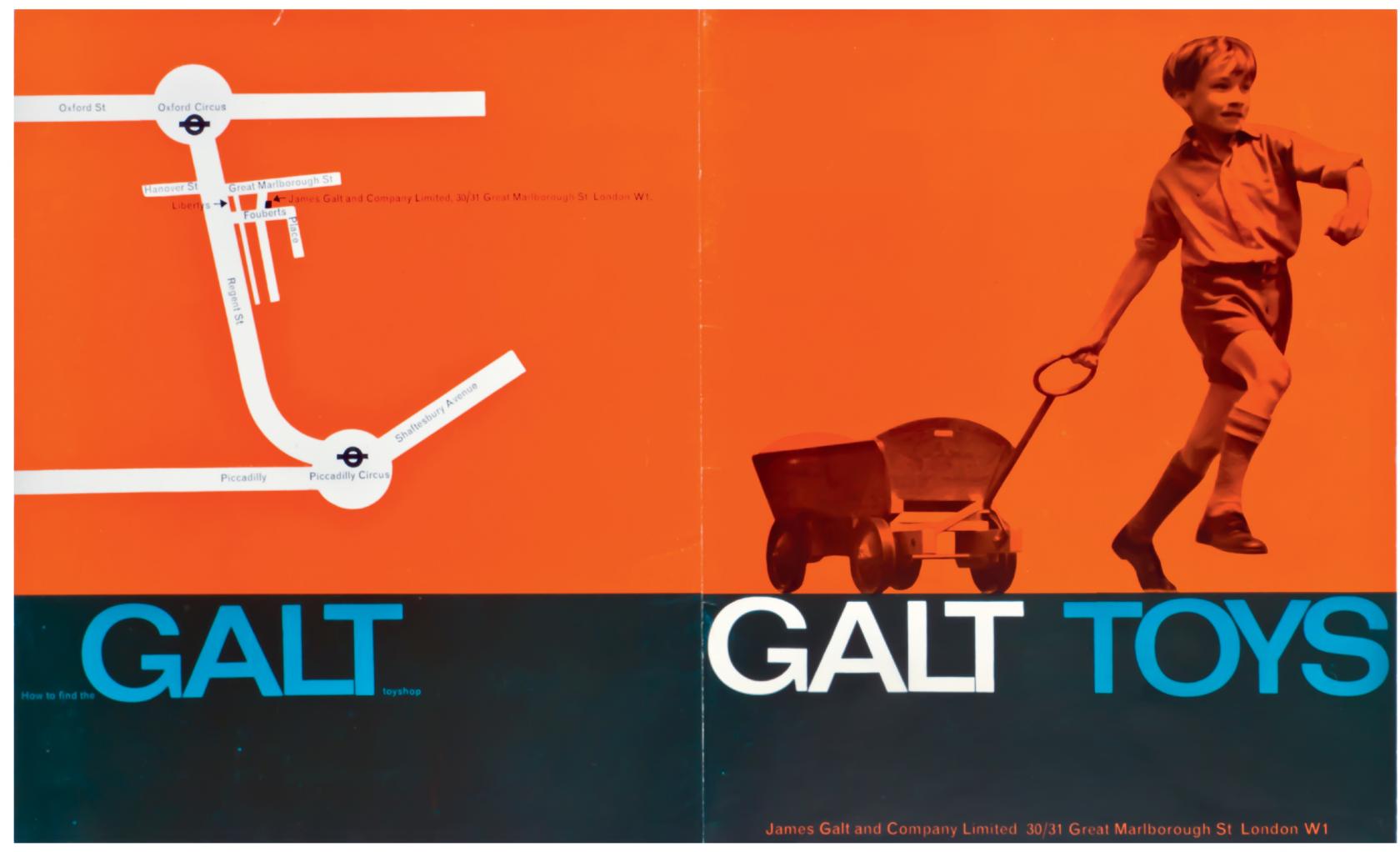

When Garland left the magazine in 1962 it had been transformed visually, if not in spirit. He set up his own consultancy, and over the years Ken Garland and Associates’ clients included Galt Toys, small furniture makers and publishers, posters, book covers and record sleeves. His ethos was to stay small and closely engaged with his clients. Although he very admired the verve of American design, and the rigour of Swiss typography, Garland was more convinced of the importance of graphic design to convey information and help shape our view of the world, not simply as a tool to drive sales. As a result, KGA was never a juggernaut churning out endless corporate identities or ad campaigns. Garland belief that the financial momentum of the ad industry was denigrating the art of design, trivialising skills and adding nothing more than noise to the visual landscape eventually resulted in the ‘First Things First’ manifesto of 1964. Signed by 21 of his peers, it urged designers to take responsibility not just for their work, but how this work could aid or abet the world around them. It was an ethical stance that garnered a huge amount of attention and which has never really been convincingly countered. In 2000, a new generation of designers revived FTF, buoyed by its rational and emotional demands in an age of ever-increasing wealth disparity.

Politics was integral to Garland’s life, most notably through his design work for CND, but also through his humanist and compassionate attitude evident in his many writings and teachings. At the Department of Typography and Graphic Communication at Reading, where he taught for 28 years from 1971, he was a hugely valued tutor (as well as ‘the life and soul of the end of year party,’ and ‘an enthusiastic dancer’, as two former students recalled). ‘Ken would breeze into the prefab typography department in Reading, wearing his trademark embroidered hat and shake us up with his playful one-day exercises,’ says the designer John Morgan, ‘To those that didn’t know Ken, you might think the author of ‘First Things First’ would be of an earnest or sober disposition. Ken was just as committed to delight and joy in design and life. With a twinkle in those eyes, full of curiosity and intelligence, he reminded us that sometimes it is better to dance first and think later.’

Galt Toys by Ken Garland & Associates

Many of Garland’s evolving thoughts and opinions were collected in a book of essays, ‘A Word in Your Eye,’ published in 1996 and still one of the most readable works on visual culture during this period of rapid change. He also wrote the definitive study of Harry Beck's original work on the London Underground map in the 1930s, a 1994 monograph that predated the enthusiasm for the stoic, no nonsense authority of British transportation design, now spilling over into all manner of ephemeral products.

Ken Garland’s legacy is one of quiet confidence, as well as unstinting support and encouragement for individual creativity. He loved the ad-hoc and the ephemeral, especially when they were very personal statements, like graffiti, but decried the visual chaos of unnecessary choice and complexity, especially when it came from large corporations. His legacy lives in a particular form of British design and typography, one that values content and consistency, modesty and restraint, but which is unafraid to let itself go when the time is right.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.