Bespoke Partnership

Four Hong Kong crafts embracing the future

Hong Kong has a rich craft tradition. Meet four artisans preserving historic crafts and updating them for the 21st century in unexpected ways

In partnership with The Hong Kong Tourism Board

Away from the luxurious boutique hotels, Michelin-starred restaurants, vertiginous apartment blocks and world-class shopping malls, and far from the nightly light and sound show over Victoria Harbour, is another Hong Kong.

Down labyrinthine back streets, tucked in basement workshops and modestly appointed, walk-up ateliers, the city’s traditional crafts and artisan skills are quietly surviving and thriving. These craftspeople and their uniquely specialised work – officially termed ‘Intangible Cultural Heritages’ by the local government – are a vital part of Hong Kong’s DNA.

The artisan mahjong carver

At Biu Kee Mahjong on Jordan Road, proprietor Cheung Shun-king plies his trade as one of three remaining artisan mahjong tile carvers left in Hong Kong. The work is detailed and specialised, requiring concentration, dedication, and skills passed down by previous generations.

Yes, Cheung is aware that people can buy a machine-made mahjong set for HK$700 (£65) at the nearby, tourist-friendly Temple Street Night Market. But each of the 144 tiles in his sets, which start from HK$5,000 (£460), is finished by hand, during an intense ten-minute flurry of creativity, with a motif that is both pleasing to the eye and sensuous to the touch.

‘Machines may be able to create a usual mahjong set, but it’s difficult and costly to create other patterns, special logos, characters or words,’ says Cheung as he uses a thin metal spatula to etch a dragon motif onto a green and ivory-hued tile. ‘I can carve different kinds of bespoke requests. People come to me asking for tiles depicting the 12 signs of the Chinese zodiac, lucky phrases in Chinese or English, and more. You can see many examples of my work on my Facebook page – my children run it for me.’

While most of Cheung’s carving knives and spatulas can be purchased at any hardware store, he also fashions some of his own tools for carving dots and bamboo suits onto the tiles. It takes time to learn and perfect the craft of mahjong-making, he admits, and it remains difficult to pass on to the next generation.

‘However, mahjong-making has seen a surge of interest in recent years. I’ve been receiving invitations to host workshops for schools, universities, companies and non-profit organisations,’ he says. ‘It is good to see people eager to learn more about the craft and try their hands at it.’

The paper effigy maker

At Bo Wah Effigies, on Fuk Wing Street in Sham Shui Po, Au-yeung Ping-chi has a new order in. A customer wants him to make a paper effigy to honour his deceased father, who was often attached to his mobile phone. Propped in the corners of the small workshop and hanging overhead are more brightly painted, completed orders – papier mâché renderings of a full-size motor scooter, an upholstered massage chair, and a child’s cuddly toy – alongside bamboo skeletons of works-in-progress.

Paper effigies, known locally as Zhizha, are an integral part of Taoist funeral ceremonies, which are common in Hong Kong. Family members will often burn paper sculptures that acknowledge real-life objects, to accompany the deceased in the afterlife. ‘It is the living showing their love and remembrance for those who have passed,’ explains Au-yeung. ‘The living hope that the deceased will be able to enjoy whatever they loved even after they have gone.’

Work since burned to ashes includes diving equipment (flippers, mask) and a scaled down but playable snooker table ‘complete with pocket holes and everything’. Au-yeung likes to describe his job as helping people ‘accomplish the uncompleted dreams of the dead’.

For generations, Zhizha effigies took the form of houses and cars. Then Au-yeung took over the family business and things began to change. ‘After my first creations – a skateboard and an arcade game dance mat, which I displayed at our shop front – gained media attention, people started giving us all kinds of requests. I elevated this traditional craft with creativity and made it more relevant to modern lives. The craft is no longer stagnant but changes with the times.’

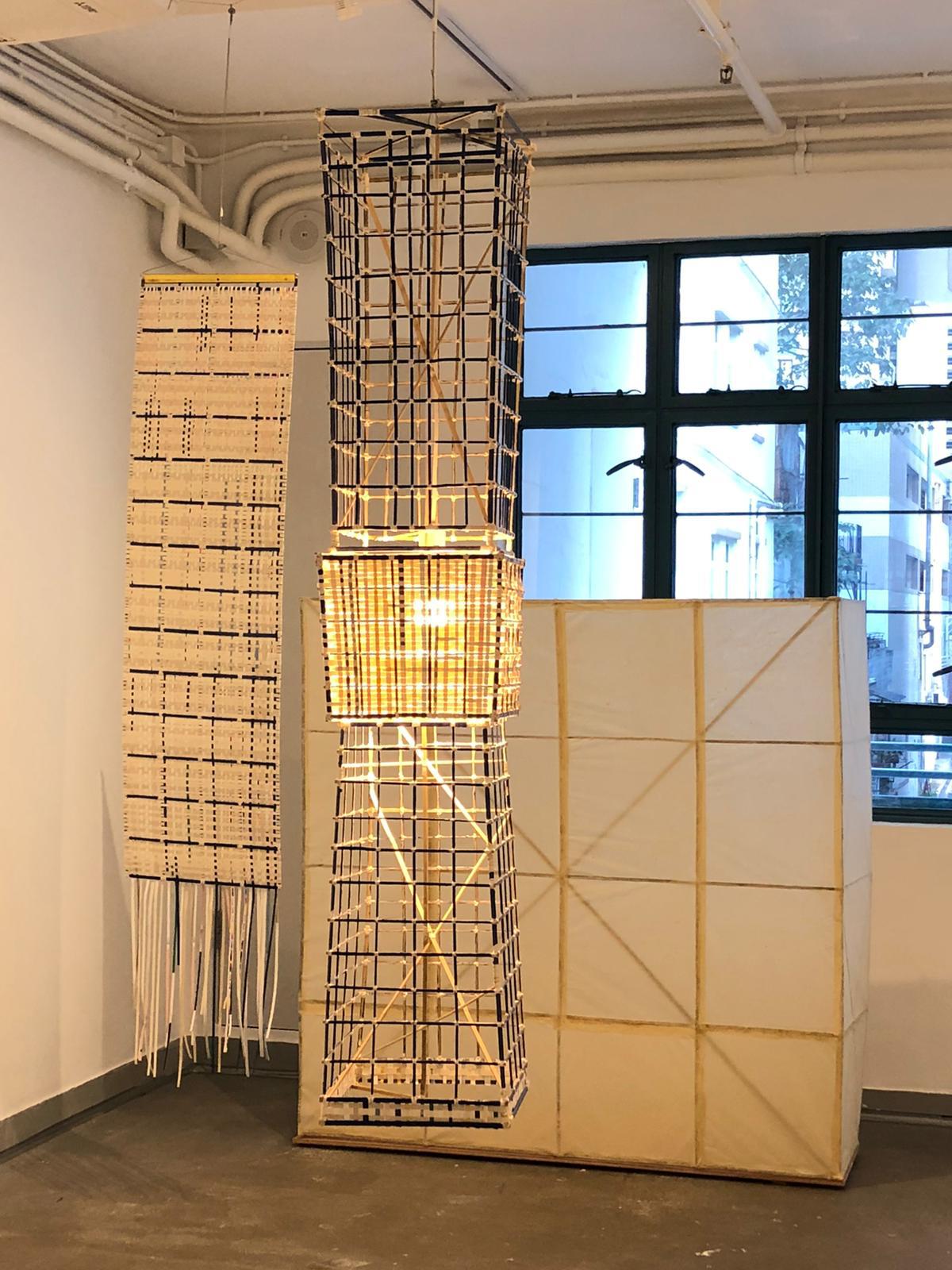

Bo Wah Effigies’ work has also been the subject of several exhibitions and is acknowledged as a bona fide art form; recently Au-yeung, who studied at Hong Kong’s First Institute of Art and Design, completed a series of lanterns for a festival at the city’s Victoria Park, and showed a spectacular mantis effigy at The Breeder, a contemporary art gallery in Athens.

In 2022 he will stage his own Hong Kong exhibition, presenting his latest works – a Nintendo games console, a drinks vending machine, a bicycle, and more. ‘People used to be scared of traditional effigies. Now they are paper art to be admired and appreciated.’

The embroidered slipper crafter

Founded in 1958, Sindart makes and sells traditional handmade Chinese embroidered slippers. Delicately detailed, they offer a gentler counterpoint to the mass-produced sneakers and logo-ed loafers on sale in Hong Kong’s designer malls.

The small Sindart atelier and shop – the oldest store of its kind in the city – is owned by Miru Wong, granddaughter of the business’ founder. Under her guidance, Sindart has diversified into casual, embroidered slippers for the home, wedding shoes, and slippers for newborn babies.

Using her skills as an illustrator, Wong has transferred drawings onto fabrics, making new and modern shoe designs. She embroiders in thread, beads, sequins and ribbons, working not just with silk but also satin, brocade, denim, linen and velvet. American interior designer and fashion icon Iris Apfel is a customer.

‘Probably the only artisan of embroidered shoes left in Hong Kong, I always emphasise the importance of handcraft,’ says Wong. ‘I believe handcrafted, embroidered shoes are a harmonious combination and demonstration of traditional embroidery skills and shoe-making techniques. This craft should be preserved, especially as the quality and cultural value are incomparable.’

In order to move forward the spirit of Hong Kong craftsmanship, Wong has organised workshops and exhibitions where people can experience the joy of embroidering and shoemaking, and at the same time, understand the history and development of embroidered shoes. ‘Some participants are even interested and engaged enough to join my apprentice training programme, which adds new blood to the industry.’

The shoemaking process, admits Wong, is complicated. Cutting, glueing, sewing and moulding. Stretching, stitching and embroidering. ‘I have learnt the skills from my grandparents and I will keep making this uniquely “Hong Kong” wearable art for the rest of my life.’

The Qipao Designer

‘People who come to my shop know my passion and skill for making a good qipao,’ says Kan Hon-wing of Mei Wah Fashion. ‘They understand and appreciate my craftsmanship, accumulated over the past 50 years.’

Kan began his career as a teenager, and has been perfecting the construction of the traditional, body-hugging, high-necked silk qipao dresses, of Manchu origin, ever since. ‘My passion for the aesthetic has kept me going,’ he says. ‘You know when you see a perfect qipao – it is form-fitting, flows naturally and exudes elegance. There’s no golden formula when it comes to creating a good one – it’s all about being attentive and accentuating the unique figure of each customer.’

Kan admits that it is increasingly difficult to pass on his particular craft. ‘It’s more time-consuming than it is profitable,’ he says, explaining that more than 80 per cent of a qipao is hand-sewn and only a few finishing touches are completed with the assistance of a machine. ‘The work requires a lot of passion and patience. There are probably fewer than ten qipao tailors in the city now; many have retired and others have passed away.’

Still, as fashions change and Hong Kong continues its trajectory as a global city, he is determined to continue this uniquely Chinese style of designing and tailoring. ‘There will always be someone who wants to wear a qipao – it’ll never go out of style, as it transcends trends and generations. Women simply look better in a qipao – the tailored silhouette lifts their grace and beauty.’

There is no hidden secret behind Mei Wah Fashion’s enduring success, no specialist machinery or mysterious technique. ‘Our tools are nothing fancy,’ says Kan with a smile. ‘Just needles, thread and a measuring tape. And a lot of experience.’

INFORMATION

For more information, visit The Hong Kong Tourism Board

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Rosa Bertoli was born in Udine, Italy, and now lives in London. Since 2014, she has been the Design Editor of Wallpaper*, where she oversees design content for the print and online editions, as well as special editorial projects. Through her role at Wallpaper*, she has written extensively about all areas of design. Rosa has been speaker and moderator for various design talks and conferences including London Craft Week, Maison & Objet, The Italian Cultural Institute (London), Clippings, Zaha Hadid Design, Kartell and Frieze Art Fair. Rosa has been on judging panels for the Chart Architecture Award, the Dutch Design Awards and the DesignGuild Marks. She has written for numerous English and Italian language publications, and worked as a content and communication consultant for fashion and design brands.

-

Seb Brown rethinks the signet ring at Dover Street Market Paris

Seb Brown rethinks the signet ring at Dover Street Market ParisHistorical and contemporary unite in Seb Brown's offbeat signet rings

-

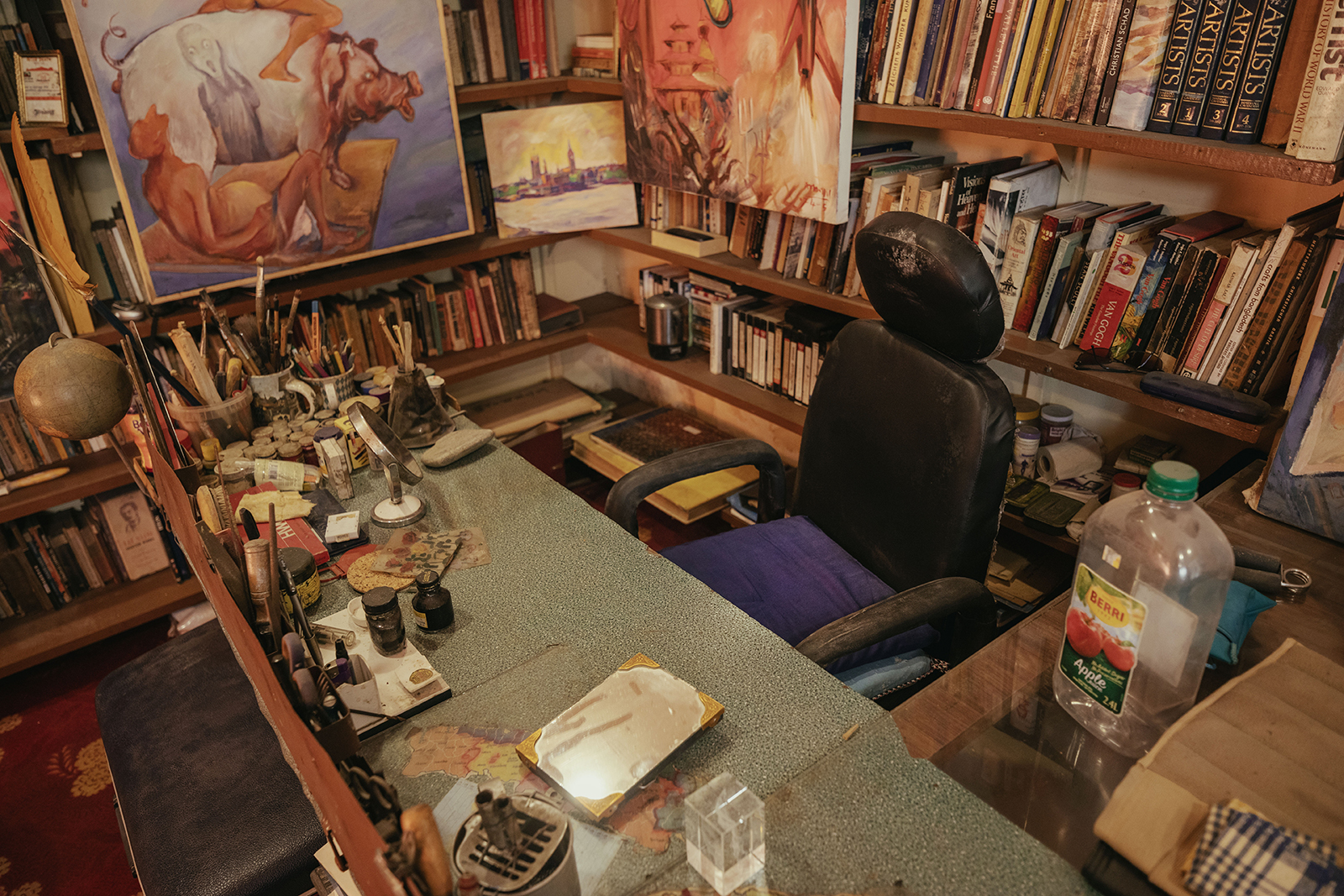

We visit the late artist Manuj Babu Mishra’s studio in Nepal, a treasure frozen in time

We visit the late artist Manuj Babu Mishra’s studio in Nepal, a treasure frozen in timeThe private studio of Manuj Babu Mishra, the late, great artist from Kathmandu, was his entire world – a self-imposed exile where he painted the chaos of humanity; his son, Roshan, invited us to visit

-

A triplex apartment in Central London blends highly crafted materials with expansive spaces

A triplex apartment in Central London blends highly crafted materials with expansive spacesThe Apartment Arabescato by Grafted is an impressive extension of a Fitzrovia flat, a showcase for craft, space and material

-

Homeware and design store Beverly’s puts down roots in New York’s Chinatown

Homeware and design store Beverly’s puts down roots in New York’s ChinatownBeverly’s was founded by Beverly Nguyen as a retail destination focused on community by supporting small business owners, creatives and craftspeople

-

Colourful playground installation brings Hong Kong square to life

Colourful playground installation brings Hong Kong square to life‘Prismatic’ is a colourful playground installation created for Design District Hong Kong by artists Craig & Karl

-

Highlights from Design Shanghai 2023: ‘Now is the golden age of Chinese design’

Highlights from Design Shanghai 2023: ‘Now is the golden age of Chinese design’Our Design Shanghai 2023 highlights, from leading Chinese designers and brands to emerging creatives

-

Shanghai’s MMR Studio is inspired by industrial processes and materials

Shanghai’s MMR Studio is inspired by industrial processes and materialsChinese designer Zhang Zhongyu of MMR Studio is inspired by industrial processes to create furniture and objects

-

China’s Designew platform explores the design of errors

China’s Designew platform explores the design of errorsThis collection of furniture and objects is the result of a new collaborative project led by designer Mario Tsai, exploring how mistakes can positively impact the creative process

-

Hong Kong art scene expands its reach

Hong Kong art scene expands its reachBeyond fairs, museums and galleries, Hong Kong’s burgeoning art scene is influencing its bars, restaurants and hotels

-

The pared-back designs of Mario Tsai

The pared-back designs of Mario TsaiMario Tsai – named by Nendo’s Oki Sato as a creative leader of the future for Wallpaper’s 25th Anniversary Issue ‘5x5’ project – talks about his experience working as a designer and entrepreneur in China, at the cusp of innovation and tradition

-

World View: Letter from Hong Kong

World View: Letter from Hong KongThe World View series shines light on the creativity and resilience of designers around the world as they confront the challenges wrought by the Covid-19 pandemic. Working with contributors around the world, we reach out to creative talents to ponder the power of design in difficult times and share messages of hope. In Hong Kong, design leaders Michael Young, Joyce Wang, André Fu, Marisa Yiu and Adrian Cheng are turning to new approaches and philosophies for the times ahead, writes our commissioning editor TF Chan.